Day 47 – Salisbury Cathedral

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, 1830-31, Tate Britain, London.

Sometimes a painting is asking to be talked about. I heard on the radio – yesterday morning I think it was – that the foundation stone of Salisbury Cathedral was laid on 28 April 1220 – 800 years ago last Tuesday. This, in itself, made me think about today’s painting, but then I was reminded of it again yesterday while writing about the Pathetic Fallacy (Picture Of The Day 46). Having said that, it was already in my mind, I suppose. Last week I was challenged to include three words in my blog – ‘crepuscular’, ‘vicissitudes’ and ‘antidisestablishmentarianism’. I succeeded with the first two in POTD 41 and 42. This is the only painting I can think of for the third.

On October 23, 1821, Constable wrote to his friend, John Fisher, saying that, ‘It will be difficult to name a class of landscape in which the sky is not the key note, the standard of scale, and the chief organ of sentiment’ – by which he meant that the sky would set the emotional tone of the painting. This is, as close as you could reasonably want, a statement acknowledging something that would not be named for another 35 years: the Pathetic Fallacy. It was defined, and discussed at length, by John Ruskin in the third volume of his Modern Painters, published in 1856. We use the word ‘pathetic’ in such a different way now. Back then it was related to feeling, as in pathos, and not to being weak. It was a mistake, or fallacy, Ruskin said, to attribute feelings (pathos) to inanimate objects – such ideas would be the imaginings of an unhinged mind. However, he did go on to say that, poetically speaking, this was not a bad thing, as long as the emotion it produced was genuine: ‘Now, so long as we see that the feeling is true, we pardon, or are even pleased by, the confessed fallacy of sight, which it induces’. Even if it gets the name of an error, the Pathetic Fallacy is one of the essential tools of the artist’s – and poet’s – craft.

It came into play a decade after Constable’s letter, when he worked on this particular painting. His wife Maria had died in 1829, and Fisher wrote to him suggesting that he might want to paint Salisbury Cathedral as a way of occupying himself during his grief – effectively a form of therapy – saying, ‘I am quite sure that the “church under a cloud” is the best subject you can take’.

Before I go any further, I should clear up a potential source of misunderstanding. Constable had two friends called John Fisher, one of whom was also a patron, and both of whom lived in Salisbury. One, the patron, was Bishop of Salisbury, and the other, with whom Constable corresponded more regularly, and in whom he confided, was the nephew of the Bishop, and was an Archdeacon at the Cathedral. This can only have led to confusion in the 19thCentury, and it still does today.

Constable’s letter of 1821 had been written after a summer of ‘skying’, as he called it – going out onto Hampstead Heath and painting the sky, so he could get better at it, and it would become easier, and more natural for him. He was already familiar with the weather. He was the son of a corn merchant who owned mills, and young John often had to man them himself. You need to know when a storm is coming, because if you don’t disable a windmill it could be destroyed. As a result he was entirely adept at reading the weather. By the autumn of 1821, he was also adept at painting it. He favoured a contrast of light and dark, of blue sky and cloud, so that the ground itself would be a patchwork of sunlight and shadow. But the sky in today’s painting is more than usually stormy: he really does seem to have taken Fisher’s suggested title, the “church under a cloud” to heart. Indeed, so bad is it, that lightning is striking the roof of the North Transept – the part of the church to the left of the crossing if you are looking at the High Altar.

Is this an autobiographical reference? I would say ‘yes’, particularly given that Fisher had suggested this very subject in his letter of August 1829. But other things were going on at the time, things in which both Johns – Constable and Fisher (Jr) were particularly interested. In 1829 the Catholic Emancipation Act was passed, and both thought this might pose a threat to the Church of England, the Established Church. Not only that, but debates were already underway for what would become the Reform Bill of 1832, one result of which was to give the vote to a large number of nonconformists. Another threat, perhaps, to the Established Church. Indeed, one subject for debate was that the church should actually be disestablished, a notion strongly contested by both Constable and Fisher, who were both ardent supporters of antidisestablishmentarianism. The church was under more than one cloud. In the painting it appears as a physical storm, with lightning striking the roof of the church. Constable himself was undoubtedly going through ‘Stormy Weather’ after the death of his wife. And ‘The Church’ as a whole – not just this building – was going through its own political storm, a result of changes in political thought. Would the Established Church survive?

The answer would seem to be given to us by the rainbow. As we saw in POTD 37 the rainbow is a symbol of hope and optimism, given to Noah as a sign of God’s covenant that he will never again destroy the earth, as he had with the deluge. Constable acknowledges this symbolism, and with it, tells us that not only will he personally be alright – he will survive his grief – but also that he knows that the church will ride the political storm. However, the rainbow was not part of Constable’s original plans for the painting: it was not in his first sketches. It is an idea which came to him later on. It is certainly not something he witnessed first hand. No one ever has – nor ever could.

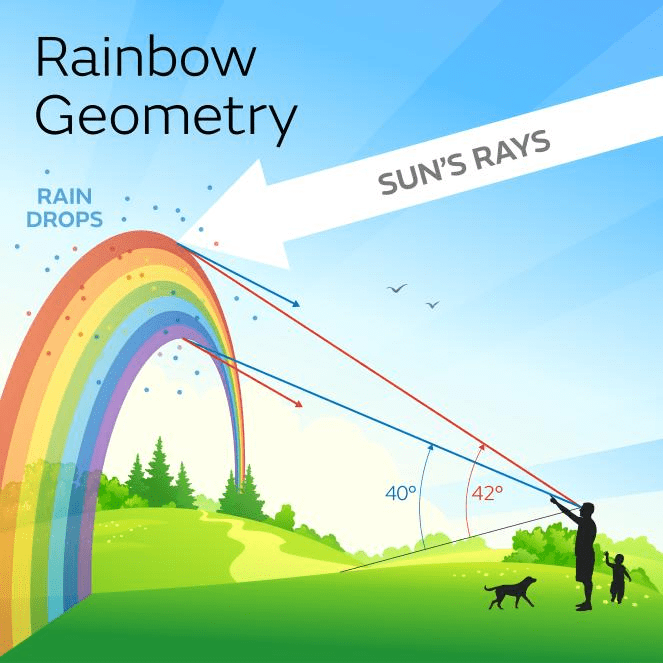

How can I be so sure? Well, it comes down to the geography of the church, which is, as churches should be, orientated: the altar faces the East (POTD 38). The North Transept sticks out to the left of the building – where we see the lightning strike – and the façade of the Cathedral that is so clearly visible (Constable was a master at manipulating light) is at the West End. The rainbow forms an arc of a circle (following the science of optics it cannot do otherwise), which appears to stretch from Northeast to Southwest, given that it cuts across the Cathedral on a diagonal. I don’t know if you know this, but you only get a rainbow when it is both rainy and sunny, and if you are looking at a rainbow, then the sun must be behind you. The sunlight travels over your head into the rain, and the light reflects back from the back of the raindrops. As it enters and leaves each raindrop it is refracted, each wavelength of light being refracted by a different amount, thus splitting white light into a rainbow. The light then comes back towards you, and makes it look as if the rainbow is in front of you. Here’s a diagram, thanks to the Met Office:

So, if we are looking at the rainbow as Constable has painted it, the sun must be behind us, i.e. in the Northwest. But Salisbury, and indeed, the whole of Europe, is in the Northern hemisphere, and so the sun never gets anywhere that is not South. It is impossible to see a rainbow in this position. But that doesn’t matter. This isn’t science, this isn’t a photograph, this is art – and the rainbow expresses hope. After all, the spire of the Cathedral passes in front of the darkest area of cloud and then up into the light. Again, this is a symbol of optimism.

Nowadays Salisbury Cathedral has gained something of a reputation as the must-see building for any self-respecting Russian spy, and they are not wrong – it is a fantastic building. The spire is the tallest in the country, and the cloister and cathedral close are also the largest in the land. The main body of the church is remarkably coherent stylistically, having been completed in a mere 38 years – not long for a building of this size that was started 800 years ago. It is well worth the visit, and, once we can travel again, I would recommend that you go. We are all “under a cloud” at the moment, but like Noah, like Constable – and like Salisbury Cathedral – we will get through it.

By the way, Constable was not being careless when he chose to paint the rainbow here. It’s worthwhile remembering that other myth about rainbows – that there is a pot of gold at its end. Even if this is, in itself, unscientific (were there no ground in the way a rainbow would form a complete circle, and so it wouldn’t have an ‘end’) there isn’t gold at the end of this rainbow, but lead. Or rather, a house, called Leadenhall. Which is precisely where Archdeacon John Fisher lived. I’ve said it before: art is alchemy, turning base metal into gold. Constable is not only showing us his gratitude to Fisher, he is also reminding us where true value lies. The gold at the end of the rainbow is friendship.

Richard, these are such brilliant essays. I am learning so much. I really hope you are speaking to your publisher about them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Judith! I will be contacting publishers at some point, I suppose, although I suspect that my picture choice is too random and personal to be of wider interest! We shall see…

LikeLike

Dear Dr Stemp,

We are enjoying your posts very much. Thank you.

I thought that you might like to see this photograph of Salisbury Cathedral which I took last year.

Best wishes, Brian Plummer.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Brian – sadly, the photo doesn’t seem to be attached. I’m not even sure if that’s possible. I’ve wandered around the water meadows several times, though, trying to locate a precise point, and enjoying the trees while at the same time lamenting the fact that some of them are now in the way!

LikeLike

PS. It was taken 100 yards away from the point where Constable painted the scene. Best wishes, Brian.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person