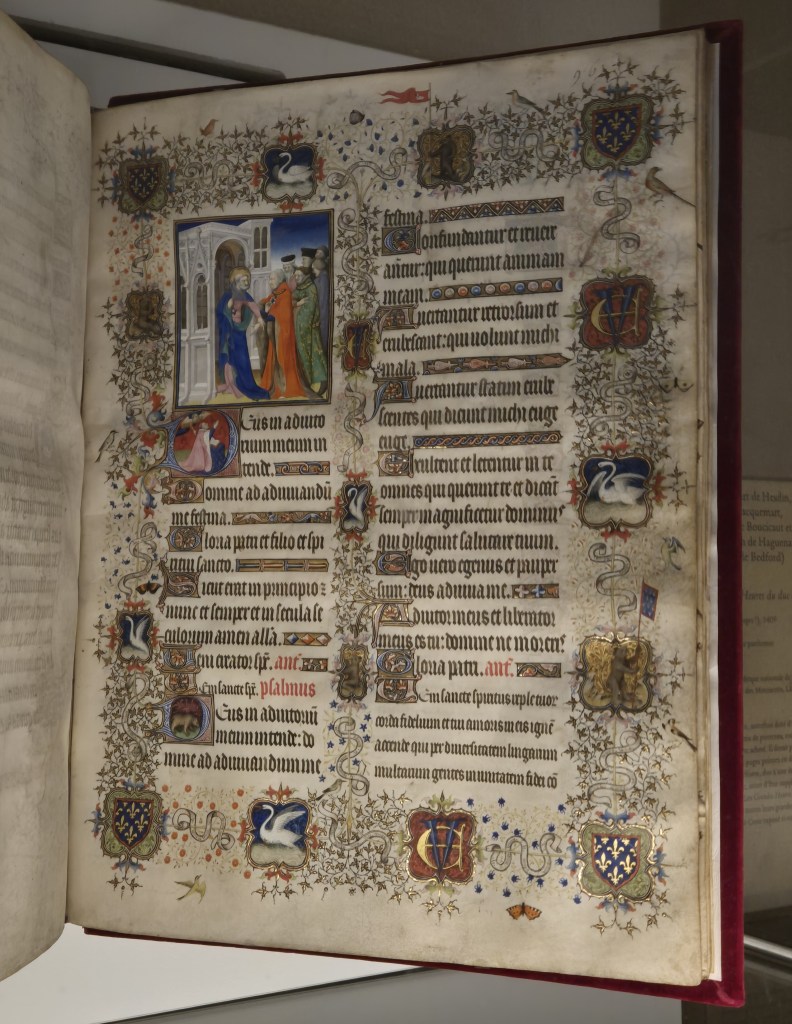

Jacquemart de Hesdin, Pseudo-Jacquemart, Master of Boucicault and Haincelin de Hagenau (Master of Bedford), Grandes Heures du Duc de Berry, fol. 96r., 1409. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

After last week’s saunter through the twelve calendar months of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, as currently exhibited at the Château de Chantilly, and the subsequent hurried leafing through the remainder of the manuscript, I am sure I will return to the book just before Christmas to look at the some of the remaining illuminations more thoroughly: they are really worthy of attention. Not only that, but it will be a treat – for myself, if no one else! This week, though (22 September), I am going to head back to Chantilly, stopping off at Saint-Denis on the way out of Paris, in order to think about The Duc de Berry: the man himself. Thereafter, as you’ll know, I’m heading to Italy and the Palazzo Strozzi’s much-heralded exhibition on Fra Angelico:

6 October, Fra Angelico 1: A Melting Pot

20 October, Fra Angelico 2: As seen at the Palazzo Strozzi

27 October, Fra Angelico 3: At home in San Marco

3 November, Fra Angelico 4: Students and Successors

(3 & 4 will go on sale on 6 October)

Subsequent talks will cover the National Gallery’s exhibitions Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists and Wright of Derby: From the Shadows. They will probably be on 17 and 24 November – so there’s plenty of time before I need to post more details. Meanwhile, my next trips with Artemisia are already online – visiting Strasbourg and Colmar (to see the astonishing Isenheim Altarpiece) in June, returning to Liverpool in September and celebrating Siena in November. There is more information in the diary

Last week we enjoyed the Très Riches Heures. However beautiful – and rich – the manuscript is, had it been finished it would have been just one of the books of hours commissioned by the duke. His library consisted of around 300 books – a large number in the days when all books were written by hand. A hundred years later, Pope Julius II had 220 volumes, housed in the Stanza della Segnatura, famously decorated by Raphael – although the Vatican Library was larger, already numbering 3,500 manuscripts by the time of Julius II’s uncle, Sixtus IV. At around the same time, Federigo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, had about 900 volumes… But still, 300 was a lot, and around 127 survive, with many of them in the exhibition we will explore on Monday. They give a remarkable sense of the man, his interests, and his personality. As well as books covering science, history, philosophy and theology, among the books dedicated to his personal faith he owned 6 psalters (books of psalms), 13 breviaries (containing the religious services for each day), and 18 books of hours (for prayer and devotion during the ‘canonical hours’, the regular cyclical of worship established for each day). Of the 18, he commissioned six of them himself. Several of them, like the Très Riches Heures, get their name from references in the inventory created after his death. To give a sense of scale, each folio of the Très Riches Heures measures 290 x 210 mm, whereas the page we are looking at today is a lot larger: 400 x 300 mm. It comes from a manuscript which would have been rather unwieldy for private devotion, which also takes its name from the inventory, which lists “les belles grandes Heures de monseigneur que on appelle les trés riches heures, garnies de fermoers et de pippe d’or et de pierrerie, qui sont en un estuy de cuir” – ‘the beautiful large Hours of monseigneur which are called the very rich hours, adorned with clasps and piping of gold and precious stones, which are in a leather case’. It might seem to be confusing, perhaps, that they were also referred to as ‘very rich’, but the size would have been most striking. Les Grandes Heures, is probably best translated as ‘The Great Hours’, as ‘great’ has far more grandeur than ‘large’…

The Grandes Heures was probably the most richly decorated of the books of hours to be completed during the Duc de Berry’s lifetime, although sadly it has not survived intact. It came into the possession of King Charles VIII by 1488 (we don’t know how), but by then it was already in need of repairs. Originally there were full-page illuminations by Jacquemart de Hesdin. These were cut out – to be exhibited, presumably – and only one has survived. Even that isn’t in a great condition. It is in the exhibition, though, and together with the one surviving full-page image, the Grandes Heures are displayed open at a single spread. This is, as ever, frustrating, but what else could they do? And there are, in any case, many more single spreads to enjoy, with some decorated on both folios. There may have been some double-page illuminations in the Grandes Heures – there are several in the Très Riches Heures – but if there were, they haven’t survived. So today, we are just looking at one page, folio 96 recto – the front of the 96th leaf.

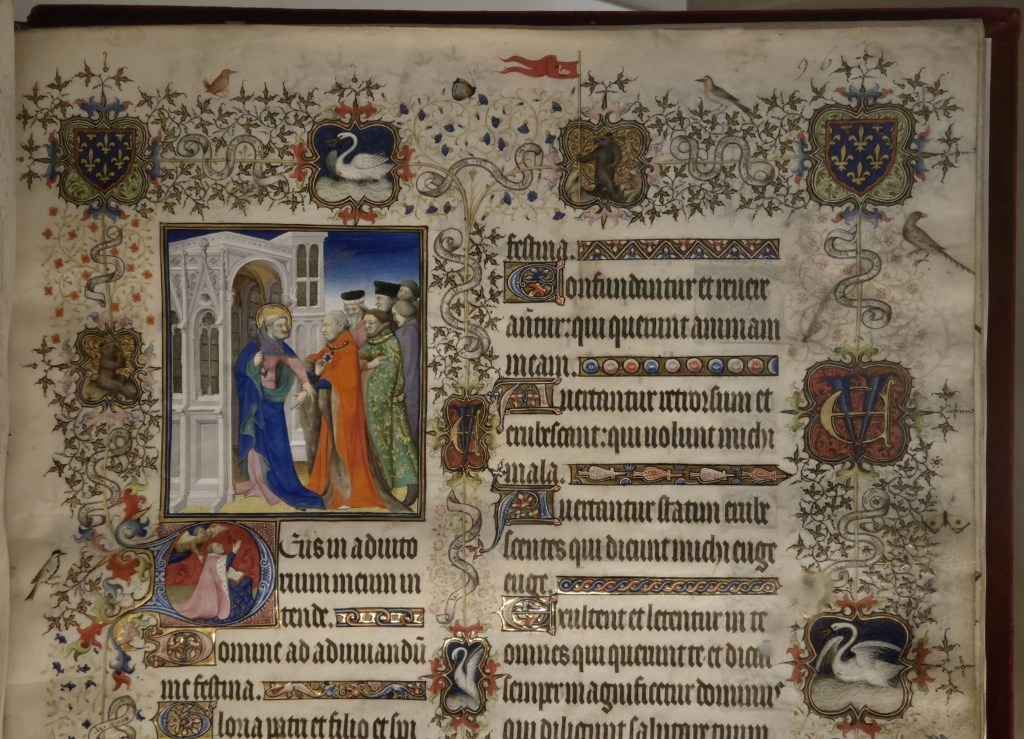

Two columns of text are framed by filigree decorations which extend the full height and breadth of the folio at top, bottom and right, with a narrower version of the same motifs on the left and between the two columns of text. There are also four vignettes at the top and bottom, and three more of the same size on the right. Smaller vignettes are included in the decoration of the left margin and in the centre. A relatively large image is included at the top left, with an illuminated initial – the letter ‘D’ – just below it. What they all represent can be seen more easily if we get a little closer.

I admit that I find the text difficult to read. The vertical strokes use to create the letters ‘i’, ‘m’, ‘n’ and ‘u’ are all the same, so that when you get a word ending ‘-ium’, for example, you have a combination of six identical strokes. On top of this, some words spread from one line to the next with no hyphens. Fortunately, though, I could read ‘Deus in ad…’ in the very first line on this page, and typing this into google instantly suggested ‘Deus in adiutorum intende’. This is followed by ‘Domine, ad adiuvandum me festina’. Together, these form the first verse of Psalm 70 (69 in the Vulgate). In the King James Version of the bible this is translated as ‘Make haste, O God, to deliver me; make haste to help me, O Lord’. This verse is used as the introductory prayer to almost every ‘hour’ that is celebrated… which doesn’t help us much. However, I can see that this invocation is followed by the ‘Gloria’: ‘Glory be to the Father, and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit. As it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be, Amen’. At the bottom of the left-hand column (not visible in this detail), the text then returns to the first verse of Psalm 70 – you can see the repeat of the word ‘festina’ at the very top of the right-hand column. This is then followed by verses 2-4 of Psalm 70, all of which are included in the detail above. It is a plea for God’s help, asking him to confound and confuse the enemies of the devout. As it says in verse 2:

Let them be ashamed and confounded that seek after my soul: let them be turned backward, and put to confusion, that desire my hurt.

However, the joyful nature of the decorations do not reflect this almost desperate sense of need. Perhaps this represents the security of the faithful (in this case, the Duc de Berry) that God will come to their aid.

All four of the vignettes in the top margin are quatrefoils – ‘four-leafed’ shapes, with points along the sides. Top left and right we see the gold fleur-de-lis on a blue ground that remind us that the Duc de Berry was a member of the royal family of France. The red border (called a bordure in heraldry), cusped and with points along the inside, tells us that he was not the eldest son of a king. Indeed, he was the third of John II’s four sons – the eldest son succeeding his father as King Charles V in 1364.

The second vignette from the left shows a swan, which first appeared as one of the dukes ‘devices’ or ‘emblems’ around 1377. Notice the red mark on its chest: it is wounded. In addition, the beak is open. Wounded, it is about to die, at which point (according to myth) swans are supposed to sing – quite literally, their ‘swansong’. In medieval chivalry this can be seen as bravery in the face of death. The wound in the heart could also be love, and the pure whiteness of the feathers, purity – in a Christian sense, the purity of love for Christ. However, the swan can also be interpreted as a symbol of romantic love: it was regularly associated with courtly love and fidelity. The myth of the Knight of the Swan was widespread across medieval Europe, and even as late as the 19th century it inspired Wagner’s opera Lohengrin (1850), not to mention the castles of Hohenschwangau (1836) and Neuschwanstein (1869). The great power of medieval and renaissance devices was that they could be susceptible to more than one interpretation, and the more meanings each had the better they were.

That is certainly true for the duke’s other main device, the bear, which he adopted before the swan. The first example dates back to 1364, and he continued to use it for the rest of his life – and even beyond. After his death in 1416 he was buried in the chapel of his château in Bourges (the capital of the Dukedom of Berry), and the heraldic beast at the feet of his effigy was a bear (we’ll see it on Monday). But what was the connection with the duke? He certainly kept bears, and, as we saw last week, he is wearing a bearskin hat in the depiction of January. But why? It helps to know the word in both English and French – and, for that matter, Latin. The French for ‘bear’ is ‘ours’, and that comes from the Latin ‘ursus’. It is not a coincidence that the first Bishop of Bourges – and indeed, the man who is supposed to have converted the town to Christianity – was St Ursinus. By choosing the bear, the duke acknowledged his devotion to this saint, and therefore also to the region of which he was made duke in 1360. In that same year, the Treaty of Brétigny was signed between the English and French, just one of the events of the Hundred Years’ War. The duke’s father, King Jean II, had been captured in 1356 at the Battle of Poitiers, and was still being held by the English four years later. By the terms of the Treaty, Edward III would renounce the title ‘King of France’, but still gained extensive territories in France. Meanwhile Jean II was held to ransom for 3 million écus, but was allowed to return home, with hostages used as a guarantee for the payment. In all around 63 men were sent to England, including two of the King’s four sons: Louis I of Anjou and Jean, now Duc de Berry. By the time Jean II died in 1464, the Duc de Berry had been in England for four years – and would remain for another five. It was at this time that his older brother became King Charles V, but 1464 was also when his use of the bear is first recorded. In the four years since he had arrived in England he must have learnt a lot of English. But then, as an educated man, he probably knew quite a bit before he went. He would certainly have known that the English for ‘ours’ is ‘bear’. And the English, who have always loved a pun (just think about Shakespeare), would surely have pointed out that, with his accent, it sounded like he was the Duke of Bear-y. And, believe it or not, most people think it’s that simple. It is worth pointing out that the bear often wears a collar, and sometimes it is also chained (it certainly is on his tomb): a captive bear, which perhaps also represents the duke’s captivity, the captivity of a strong and valiant warrior.

Some years after his death his great nephew, René d’Anjou, suggested that, in England, the duke had fallen for a woman called ‘Ursine’ – but my guess is that that is pure imagination… Given the homonym of ‘bear’ and ‘Berry’, and the existence of St Ursinus, we already have enough potential sources for his choice. In the vignette above, the bear carries a banner – red, with a white swan. Either the bear is one of the duke’s followers, or even, the duke himself: there is a strong sense of identification. Scattered about the margin in the detail above there are also a wren, a butterfly, what might be a thrush, and a pheasant – wonderful, naturalistic details, just for the joy of it, it would seem.

In the lower half of the page there are two more swans, and three more bears – one walking on the grass, another climbing a tree and a third wielding the duke’s royal standard, with its red bordure. There is also, at the bottom, a slim greenfinch and a large tortoiseshell butterfly. Another butterfly, a red admiral, can be seen above the swan in the left margin. At the top right there is a blue tit (I think – the colours are right, but it’s very long and slim) and further down, a beautifully delicate goldfinch. As elsewhere on the folio, the vignettes are joined by what appear to be the stems of the highly stylised vine, around each of which is wrapped a narrow scroll. To see what that is we will have to look closer.

It may still be too small to read, but each version of this scroll is inscribed with the same phrase twice: ‘le temps venra’. This is medieval French, meaning ‘the time will come’. Elsewhere the same idea is stated in a slightly different way: ‘le temps revient’ – ‘the time is coming back’. I’m intrigued by this, as the second version was one of the mottoes of Lorenzo the Magnificent of Florence – and he also used it in French, with a sense of medieval chivalry. The meaning is not entirely different from the soundtrack to Tony Blair’s New Labour: ‘Things can only get better’. The idea, in all cases, is that we are in good hands, that things will be managed well, and the time is coming that we can Make Berry, (or Florence, or the UK) Great Again. Enough said.

There is another ‘device’ or ‘emblem’ in this detail: the letters ‘EV’ written as a monogram – there are several examples on the page as a whole. The ‘V’ could be meant as a ‘U’ – they are often interchangeable. However, its meaning remains a mystery, even if there are several ideas. One suggestion is that, as a ‘U’, this could be an abbreviation of ‘UrsinE’ – the woman for whom the duke is supposed to have suffered love. I find this interpretation a little dubious. It could stand for Eveniet Tempus, Latin for ‘le temps venra’, while a third idea is that it stands for the words ‘En Vous’ – ‘in you’, as in ‘I believe in you’. This would be a sign of the Duc de Berry’s devotion to the Virgin Mary (with the ‘V’ also standing for ‘Virgin’). But, as I say, no one has been able to pin it down. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that the Duc de Berry was a religious man.

At the top of the folio we see him twice. He is in the centre of the illuminated capital ‘D’ of the word ‘Deus’ – God. In a pink, ermine-lined cloak he kneels at a prie-dieu covered in the fleur-de-lis and royal blue of the house of France. An angel puts one hand on his back and points up – towards heaven, or towards the image directly above, which might be the same thing. The duke looks in the same way while holding his hands aloft in prayer. To the left of this, in the margin, is a rather slim coal tit, and above it yet another bear which, like the duke, also appears to be praying.

In the larger image we see the duke again, this time wearing a red, fur-lined cloak, and holding a jewel which hangs from a thick gold chain round his neck. He is followed by a number of courtiers. More relevant, though, is the fact that his left wrist is being held by a man with short grey hair and a short grey beard who wears a blue cloak. He also has a halo and holds an enormous silver key in front of his shoulder: this is St Peter. A white dove descends from heaven, followed by diagonal beams of light: Peter is clearly inspired by the Holy Spirit, and stands in the round-topped entrance to what is otherwise an elaborate gothic porch with glazed windows. As St Peter is holding the key to the Kingdom of Heaven – as promised him by Jesus – I can only imagine that these are the very gates. In the smaller image Jean, Duc de Berry, humbly kneels in the first letter of the word ‘Deus’, and prays ‘Make haste, O God, to deliver me; make haste to help me, O Lord,’ while the angel is pointing him towards his reward: being led into Heaven by none other than St Peter himself. Judging by this manuscript – and everything else we will see on Monday – this would be a wonderful way to go.

Dear Richard, I know I am making the same comment as I made in last Monday’s lecture, but I do appreciate how you are able to pick out so many little details that enrich the experience of looking into a special seeing. Thank you. Warmest regards, Elizabethmarie Hamer

LikeLike

Thank you – it’s just looking, really!

LikeLike