Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654. Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Some paintings are so simple they seem obvious, while others simply defy explanation. I feel certain that today’s painting falls somewhere between the two: a painting of a bird that has somehow become an international celebrity, with an expression as inscrutable as the Mona Lisa, or, closer to home, The Girl with the Pearl Earring. Indeed, the subjects of these two Dutch paintings glance over their shoulders to look at each other from the opposite sides of the room. Or at least, they did ten years ago when I last saw them together, and I presume they still do: I’ll find out within days. However, despite the fame of the avian protagonist, the artist responsible remains relatively unknown. But then, he did die tragically young. I want to celebrate him this week, on Monday 6 May at 6pm, when I will talk about Carel Fabritius and the Art of Delft – making it clear that it is Not Just The Goldfinch. I’ve realised that there won’t be a huge amount of ‘Delft’, to be honest, as Fabritius’ works, however few, are so interesting that I will spend most of the time with them. While we’re about it I can recommend Laura Cumming’s Thunderclap most highly. It is a personal memoir about growing up with art, and its value for our lives, framed by encounters with the Dutch master’s paintings.

The week after Not Just The Goldfinch I will be in Delft – but the following Monday, 20 May, I will talk about Tate Modern’s powerful, colourful exhibition Expressionists. This will be followed (27 May) by another Tate exhibition, looking at the tireless, totally committed, and sadly misunderstood Yoko Ono. I’ve also set up the next set of In Person Tours of the National Gallery, which will be the last ones before a summer break:

Monday 17 June at 11:00am: NG05 – Siena in the Fifteenth Century

Monday 17 June at 2:30pm: NG06 – Piero and the Court of Urbino

Tuesday 18 June at 11:00am: NG07 – Perugino and Raphael (morning)

Tuesday 18 June at 2:30pm: NG07 – Perugino and Raphael (afternoon)

If you missed The Last Caravaggio I will repeat it next week, on Thursday 9 May at 6pm, for ARTscapades. And if you’re not free then, unlike me they have the personnel to post a recording online – so you can catch up with it within the following fortnight or so. Any other events will eventually get posted on the diary – although admittedly I have been known to forget things (as indeed I did for next week’s talk). But now: The Goldfinch.

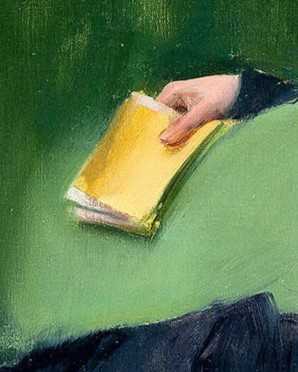

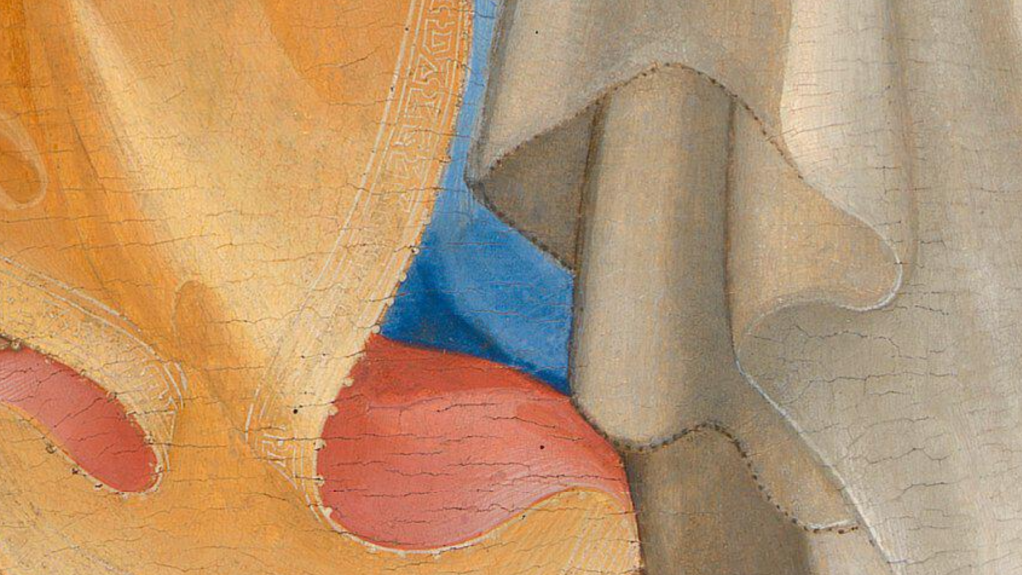

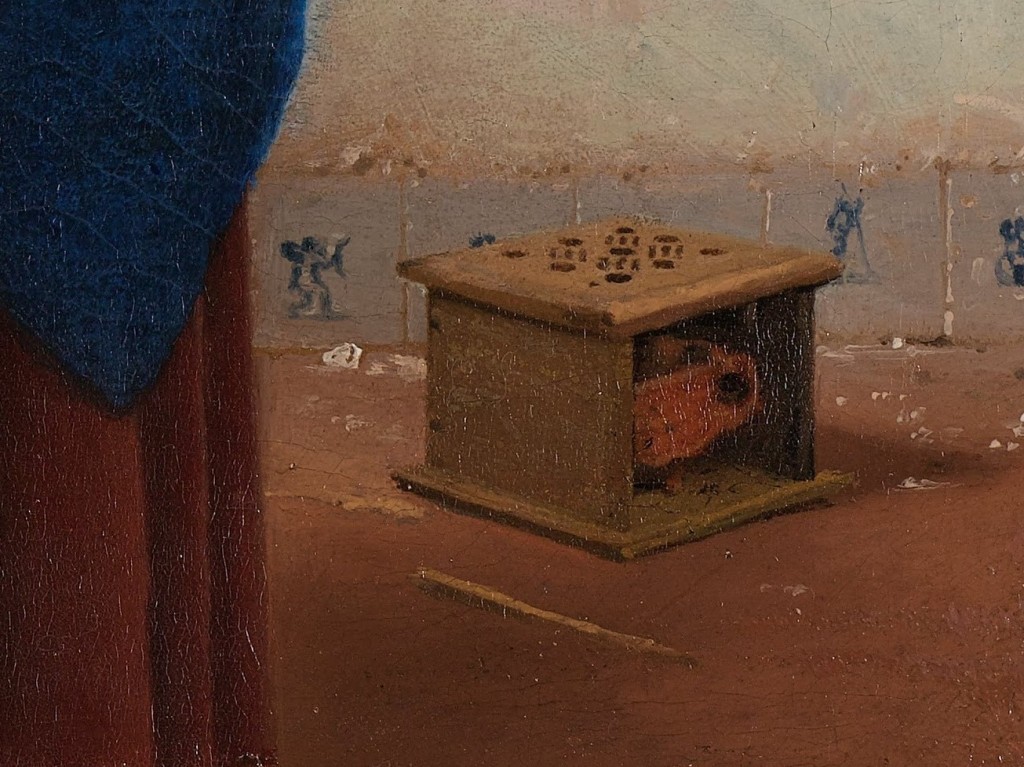

A description of this painting could be so simple: a bird stands on a semi-circular perch – the upper one of two – its body facing to our right, while its head is turned to look over its shoulder, almost as if it is turning to look at us. The two perches curve around a grey box, which is supported by two similarly grey brackets against a cream coloured wall. The bird is evidently captive: a ring is threaded around the top perch, with one end of a chain attached to it. The other end secures the goldfinch. The chain hangs behind the lower perch, and loops down between the two brackets. The red colouration of the bird’s face, and the golden flash on its wing, tell us it is a goldfinch.

Each separate colour of the plumage is applied with distinct brushstrokes, which are carefully, and on the whole thinly, applied. The exception is perhaps in the yellow of the wings, which seems to have been built up more thickly, an effect known as impasto. Elsewhere the thin strokes do not entirely cover the layers of paint which had been applied earlier, leaving gaps which help us to build up a history of their application. Somehow this technique adds to the feathery texture. At times the strokes were applied ‘wet on wet’ – and the brush has picked up the earlier paints to create streaks of colour – a ‘feathering’ of different paints particularly clear in the buttery brown brushstroke just under the top of the black section of wing, which continues down to the shadow created by the raised yellow feathers. The way in which the paint has been applied suggests that the brush was stroked and dabbed onto the painting to fill in areas of colour with the required subtlety and delicacy – although there is never any attempt to pretend that this is not a painting. On this small scale it looks remarkably painterly. We see the materials involved and the manner of their application, unlike the work of a slightly older artist, also a student of Rembrandt, Gerrit Dou, who is known as a fijnschilder – a ‘fine painter’. His works barely hint at being paintings, their making disguised in a bravura display of what we would now see, anachronistically, as photographic: a highly detailed naturalism. Not that Fabritius shies away from illusion. Look at the thin, gently undulating lines on the perch, strokes with tiny brushes that span the gap between the ring and the goldfinch’s tail, which show the light glinting off the perch. Above and to the left of the ring three small strokes likewise glint off the joint of a hinge: the grey box has a lid which is attached to the wall, and could be lifted up – presumably by the goldfinch itself, looking for food, or maybe water. The Dutch title for this painting is Het puttertje. De put means ‘the well’, and de putter ‘the water drawer’ – someone who draws water from a well. The last syllable, ‘-je’ is a diminutive – ‘the little water drawer’. In the Dutch Republic, goldfinches were trained to pull up water from a bowl in tiny thimble-like buckets. Maybe it’s the protestant work ethic.

What is the point of this detail, you might ask? There is no more information than in the last one – less, if anything, as we can see neither the perch nor the chain. But we can see the background – and there is a lot of it, compared to the size of the Goldfinch. Fabritius was a master of painting walls, creating the texture of the rough plaster with scumbled layers of closely matched paints. He was also a master of negative space: he does not focus in on his subject, as others might, framing them tightly and pushing them forward. Nor does he proclaim the goldfinch’s importance by placing it top centre of the visual field. It is some way down the painting, and off to the right – which only serves to make it seem more real. This is the full width of the top of the painting – which shows you how much space there is to make the goldfinch stand out, to convey its diminutive size, and also, perhaps, its vulnerability. If you look carefully around the edges – at the top, left and right – there seems to be a narrow border which has been painted over. This is part of the original setting of the painting, but I’m afraid I don’t have the space to go into that today: I’ll have to leave it until Monday. It is particularly relevant to Delft! The light comes from the top left, from over our left shoulders – you can see that from the bird’s shadow, below it and to the right.

The direction of the light is confirmed by the shadows of the perches, the upper one cast on the grey box, the lower one onto the wall. And while the shadow to the right of the box may seem to contradict this – the angle goes up to the right – this is the result of the scalloping of the bracket, curving from thin to thick as it goes up. Notice how both perches look as if they curve up from the wall on either side. I have little doubt that they were, in fact, horizontal – this is just a clue that we are looking up. The goldfinch is perched above our heads. To the right of the lower perch, a small area of paint has flaked away, revealing grey plaster underneath. To the right of this there is a clear vertical line which is another remnant of the original setting – which must, as we have just seen, have been high up. However painterly the style – look, for example, at the single, vertical stroke at the top of the right bracket, disguising the brown layer beneath, but barely hiding it – the chain itself is exquisitely delicate, every single link traced onto the surface, with those at the top left glinting in the light, as does the ring which allows the goldfinch a limited freedom of movement, flying back and forth in a prescribed arc, with barely enough space to flap.

There is yet more space at the bottom of the painting, again allowing the subject to be seen and understood. Space can be a luxury, and here it adds status: in the middle of this pictorial void is something that deserves to be seen. At the bottom (which is closer to our eyeline, if we are looking up at the painting) is the signature, carefully inscribed in capital letters on top of areas of re-worked paint as if it were drawn on the rough surface of the wall itself. It was 1654, the year in which Fabritius would die at the age of 32.

As I suggested above, his few remaining paintings (thirteen are generally accepted) reveal that Fabritius had a truly original sense of composition. The painting is by no means symmetrical: we have already seen how the goldfinch is on the right. However, the box and the perches are placed exactly symmetrically on the central vertical axis, while the top perch skims the central horizontal: underneath the apparent freedom is a rigid geometry. The bottom of the chain hangs to the right of centre though, implying the movement of the bird, which just happens to stand with its body lined up along the diagonal from top right to bottom left: nature organised by art, a celebration of illusion. There is also a sense of trickery. The shadow of the bird, and of the two perches, assure us that the light comes from the top left. And yet, the shape of the brackets, and the positioning of the bird, make the shadow of the box look as if the light is coming from the bottom left – but this is just Fabritius playing with our expectations, I think: the shadow is entirely logical, even if it is unexpected.

What does this all add up to? Art historians have struggled to interpret the painting: what does it mean? Or is this the wrong question? Does it mean anything at all? Or is it pure observation? And if so, why was it painted? Why this particular subject? None of the answers are entirely satisfactory, and we fall, as I said at the beginning, between unnervingly simple, and enigmatically sublime. One thing, though, is certain. If you have ever felt sorry for the goldfinch, trapped in its limited world, don’t worry – because there is no goldfinch. There is only paint. We can see how the paint was applied. We can see the layers, and the way the colours blend. We are also told, in a tract of painting that is – not coincidentally, I’m sure – exactly the same width as the distance between the outside edges of the brackets, the name of the man who painted this, and when he did it. So we can have no doubt that this was made. It is a fabrication. Fabritius was a man who made things. And yet, we believe in the goldfinch. One of the things that this painting is about – and there could be many – is the magic of art, and our willing suspension of disbelief that turns a mixture of oil and dirt into a delicate creature, living and breathing – and potentially, even, singing – just above our heads.