Frederic Leighton, The Garden of the Hesperides, c.1892. Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight.

After some delay I will be very happy to talk about Frederic Leighton and Flaming June at last – this Monday, 22 April at 6pm. This is a superb opportunity to focus on a painting which is widely recognised as the masterpiece of a former President of the Royal Academy, especially as its usual home, in Puerto Rico, is not exactly on everyone’s doorstep. The following week, 29 April, I will look at The Last Caravaggio, putting the National Gallery’s two-painting exhibition into the context of the artist’s life as a whole. On 6 May I will look at one of Delft’s leading artists, Carel Fabritius – making it clear that his work was Not Just The Goldfinch. This will be followed by Expressionists (20 May) and Yoko Ono (29 May), which will both be introductions to exhibitions at Tate Modern: keep your eye on the diary, as they will go on sale as soon as I can get myself together. The May In Person Tours are selling fast, but there are still a few tickets left for each:

Wednesday, 8 May at 11:00am NG04 – Florence: The Next Generation

Wednesday, 8 May at 2:30pm NG05 – Siena in the Fifteenth Century

Thursday, 9 May at 11:00am NG06 – Piero and the Court of Urbino (morning)

Thursday, 9 May at 2:30pm NG06 – Piero and the Court of Urbino (afternoon)

But for now, rather than Flaming June, I would like to talk about a different painting by Frederic Leighton.

When I started writing this post a few weeks back I was sitting more or less directly underneath it, as I was in the café of the Lady Lever Art Gallery. I was sitting there because (a) I wanted to have another look at the painting, (b) they do great scones, and (c) they have WiFi, and at the time I didn’t, which is why Monday’s talk was postponed. The Garden of the Hesperides was first exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1892 – which is what gives it the date ‘c. 1892’. However, it is neither signed, nor dated, so we don’t know exactly when it was finished: it could have been completed the previous year, given that many artists built up their annual submissions to the Summer Exhibition gradually, in between shows. Indeed, it might even have been started before the 1891 exhibition. Leighton’s paintings, like those of many artists of the time, function as a sort of ‘stylistic chain’, with ideas developing from one painting to the next. In each case he would make choices to resolve the problems arising from the chosen subject, and the alternative solutions to these compositional concerns often inspired subsequent works. The importance of The Garden of the Hesperides for the development of Flaming June is the reason I chose to write about it today – even before I realised that it was just around the corner at the Lady Lever: it’s only a quarter of an hour’s stroll, so even closer than the Walker.

Before we go any further, it would be good to clarify who the Hesperides were – but it’s really not that simple. If you want all of the suggestions about them (at least, I assume they are all there) you could do worse than look at the Wikipedia page, but the Encyclopedia Britannica entry is undoubtedly clearer – if less detailed. Suffice it to say that the many and varied classical sources suggest there were anywhere between three and seven of them (although a chest designed by Edward Burne-Jones in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery only includes two), and they were blessed with a large number of possible names. Leighton settles on three, which was the ‘original’ number, and the most commonly accepted. Hesperos means ‘west’, with Hesperus as one of the names for the evening star, which is seen in the west, and associated with the setting sun. As a result it was often assumed that the Hesperides lived on an island to the ‘west’ of the known world, just off the coast of Spain. I’ll feed in more information about them as we explore the painting.

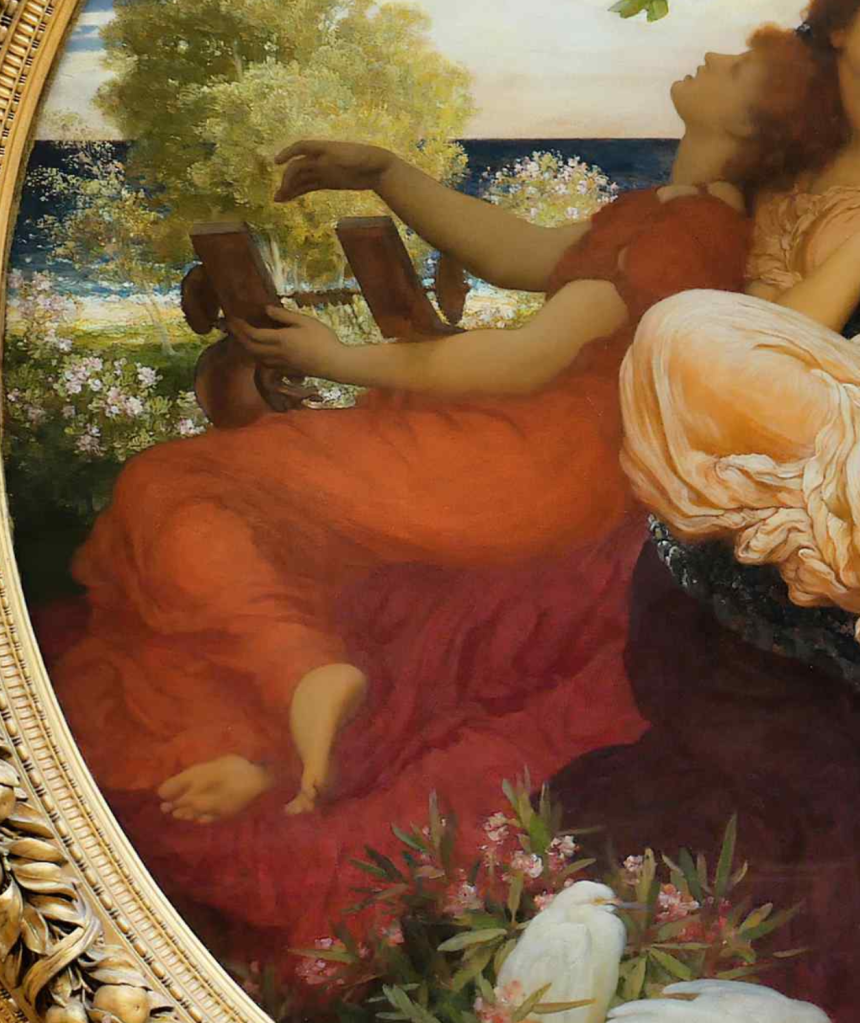

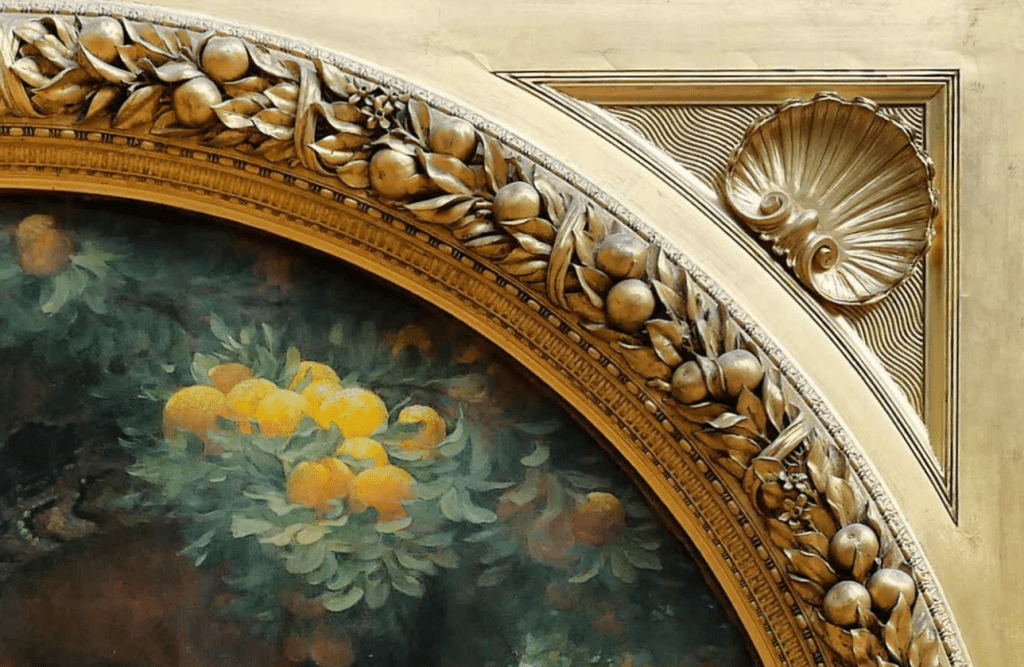

If we were talking about a renaissance work of art we would call this a tondo, a circular painting. It is displayed in the original frame designed by Leighton himself. The three Hesperides are sitting in the shade of a tree, which has a massive and gnarled trunk growing from bottom left to top right, the branches forming a canopy across the top of the tondo. The main role of the Hesperides was to tend their garden and guard this tree with its golden apples. The fruits were highly prized, and feature in a number of myths: The Judgement of Paris, Hippomenes and Atalanta and the 11th Labour of Hercules to name but three. The tree was a gift from Gaia, goddess of the Earth, to Hera on the occasion of her marriage to the ‘King’ of the Gods, Zeus. If you’re more familiar with the Roman names, that would be the wedding of Juno and Jupiter.

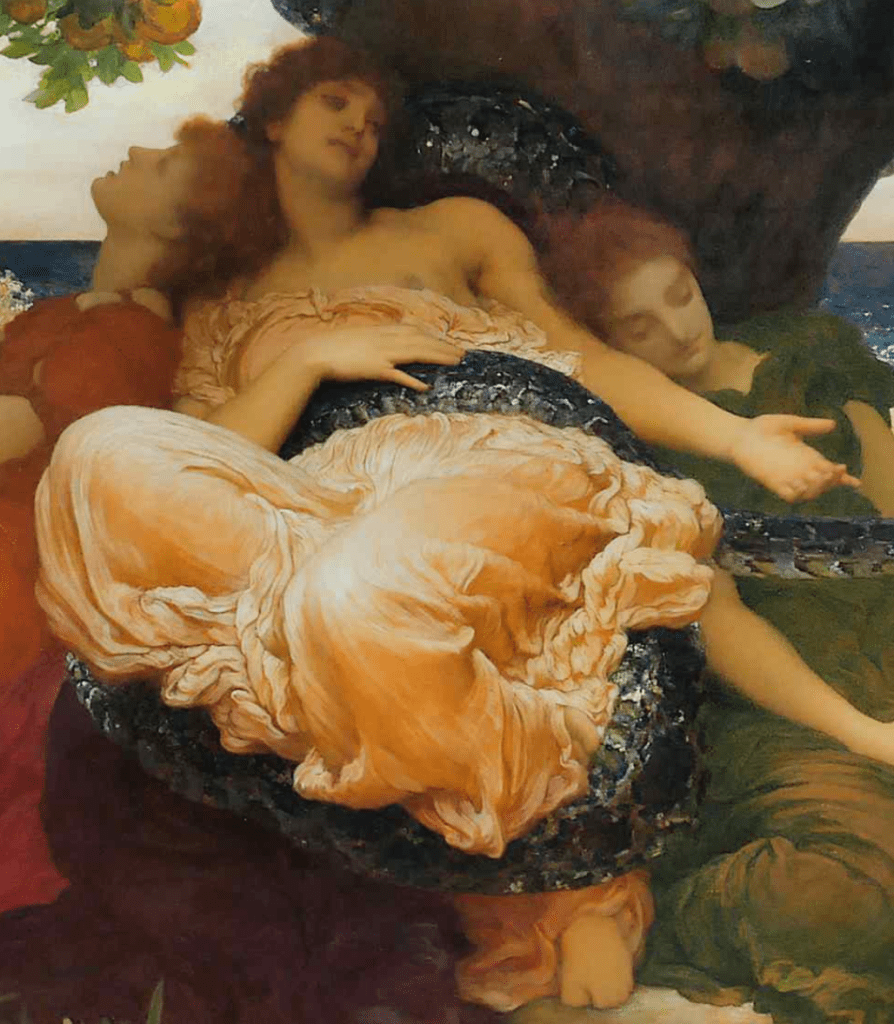

The three women sit – or sprawl – in relaxed poses, their heads lolling to one side, their eyelids drooping. It is sunset, after all (look at the orange glow on the horizon), and they appear to be in a state of eternal drowsiness. I spent a long time trying to find a good, high-resolution image of this painting to pick out some details, but they all seemed to be slightly out of focus. Finally I realised that they are out of focus. However crisp the intricate folds of the central light orange dress might appear, the faces are all slightly blurred, and that was Leighton’s intent: this is a painting of drowsiness. If I’m honest, they all look just how I feel when I’m nodding off to sleep in an armchair after a rather good lunch. We see different aspects of the three maidens: on the left, in profile; in the centre, facing towards us; and on the right, at an angle. They all rest on the trunk of the tree alongside another, unmissable presence: the serpent Ladon, who helps them keep guard, and who, I would suggest, is the only one lively enough to do so.

The Hesperides were described by Hesiod as being ‘clear voiced’, while Euripides called them ‘minstrel maids’ – apparently they delighted in song. The nymph on the left is indeed strumming at a lyre, her lips parted, as if she is singing. Her brilliantly coloured dress would suggest that she is Erytheia – ‘the red one’. She leans back against the trunk of the tree, with her torso at the same angle, and her head tilted back. Her profile stands out clearly against the pale, evening sky, and the sharply defined line of the sea on the horizon almost cuts into her throat as she sings. Her right arm, shadowed and relaxed as it nonchalantly plucks at the strings of the lyre, stands out against the brilliantly lit trees growing by the sandy beach at the water’s edge. She sits on a red cloth only a shade deeper than the deep orange (rather than red, if I look again) of her dress. This is precisely the exploration of close shades of similar colours which interests Leighton in Flaming June. This nymph also has similar, exaggerated bodily proportions to those seen in the later painting. Compare the length of her torso, from shoulder to hip, as she leans against the trunk, to her thigh, from hip to knee. The latter is enormously elongated, adding to the sense of drawn out drowsiness. This lengthened thigh becomes one of the central features of Flaming June. The lower leg – from knee to foot – is relatively short by comparison. The angle of her right leg reveals the sole of her right foot, while the left foot, propped up on the flexed toes, shows the only tension in her body. In my mind this is an echo of the right foot of the right hand angel in Michelangelo’s Manchester Madonna – but I could easily be wrong.

The central figure wears a light orange robe – I suppose it could be described as ‘peach’, or a light ‘salmon’. This may be Leighton’s representation of Hesperia, whose name means ‘sunset glow’. Her figure epitomises the contrast between crisp focus – seen in the clear definition of the legs beneath the skirts, and the multitude of rippling folds in the thin drapery which surrounds them – and the lassitudinous blur of the face, lolling to one side in the shade of the tree. Seen closer, this detail reveals that none of the three nymphs are actually resting against the bark itself: they are using the serpent Ladon’s long sinuous flank as their pillow. The loops and curves of his form are not easy to trace, but there is just a hint of the metallic sheen of the scales to the left of the tree at the top of this detail, and lower down it curves behind the heads of the three Hesperides. Ladon also encircles Hesperia, wrapping around her shins and across her waist, where the light touch of her right hand tells us that this is in no way stressful – it could even be comforting. The thinner form of the creature leaves the detail on the right, almost as if leading on from Hesperia’s gesture. The nymph’s right knee is tightly bent, the left knee less so – a posture which goes back to the Torso Belvedere, which was much favoured by Michelangelo. A variation of this composition, with the foot of the fully flexed leg tucked under the more open knee, is also adopted by Flaming June: we will look at its origins in more depth on Monday. Also derived from Michelangelo is the ruching of the fabric around an element which binds the form. Here Ladon causes the bunching of the fabric, whereas in the paintings and sculptures of Michelangelo it is often a belt or ribbon.

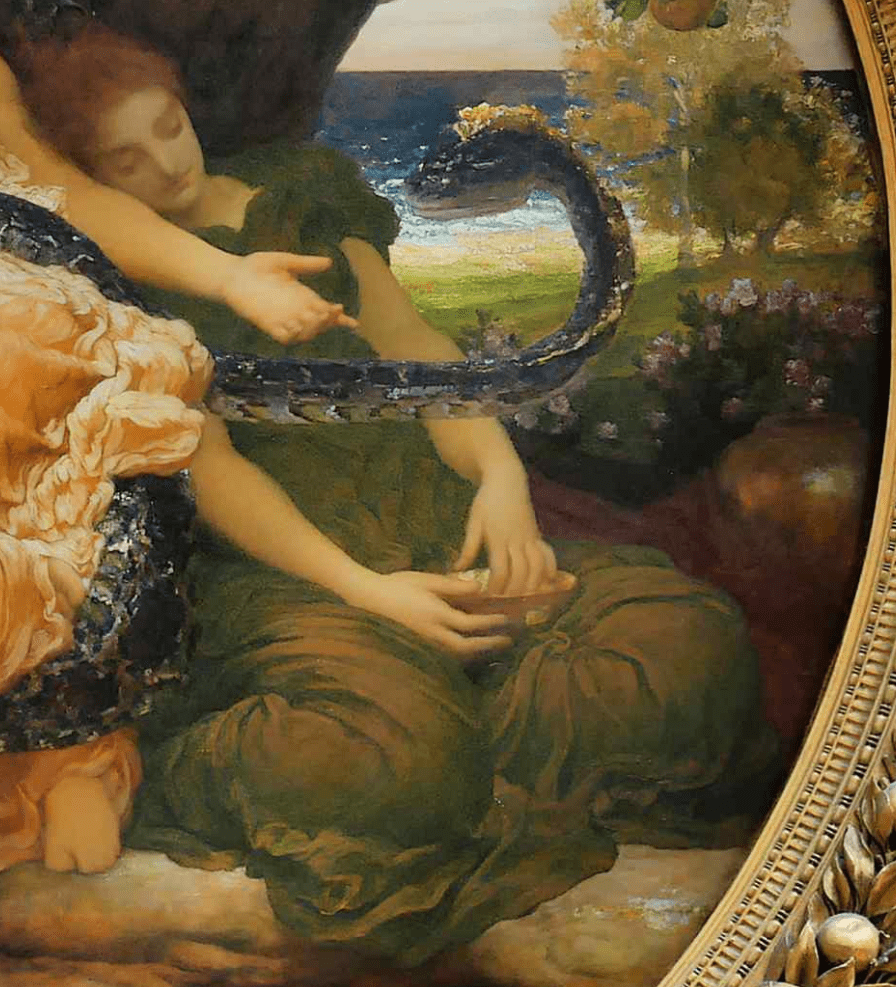

If we are following the most ‘popular’ sources, the name of the third nymph should be Aigle, but as this means ‘dazzling light’ I can’t see that this was necessarily Leighton’s intention. This painting adopts a palette which was one of his favourites in the 1890s, exploring the ways in which colours are affected by the light. Here the olive green of the robe is inflected by the warm glow of sunset. It could be catching light reflected from Hesperia’s dress, or it could be a shot silk, with warp and weft made of green and orange threads. While the back of her head lies on Ladon’s flank, this third nymph also leans on her sister’s arm. She holds a dish on her lap, and lazily fingers its contents – but it is hard to tell what they are: a pot-pourri of sweet smelling petals, perhaps?

This is a truly sensuous painting, with references to all the senses. Sight is primary: we are looking at the painting after all, but we also hear the sound of the lyre. Whatever is in this bowl, it is being touched, and if it is not also sweet-smelling in itself, we will see later that a beguiling scent is essential to the meaning of the painting. But how about taste? We will get to the ‘golden apples’ on the tree later, but to our right of ‘Aigle’ is a ceramic jar, which may contain wine. Behind it are pink flowers, which again allow the possibility of fragrance. However, in this detail, it is really Ladon who stands out, his head bold against the glistening sea. His role, as I have said, was to help the Hesperides guard the golden apples, and he certainly seems to be the most alert of those present. In one version of the myth of Hercules, his 11th labour involved stealing one of the golden apples – he slayed Ladon and took the apple from under the noses of the nymphs. In another version, while Hercules held up the sky for Atlas, Atlas was able to get into the garden easily: he was commonly believed to be the father of the Hesperides.

Looking back to the three nymphs I can’t help but admire Leighton’s composition and colour. He has painted three women who are similar enough to be sisters, but in three different poses, all of which are relaxed and sensuous, using a harmonious palette which speaks of the dusk, and of the sun setting over nature. I am also intrigued by the way he varies the focus on the figures, and creates different depths of form, almost like a sculptor. If you imagine the three women as if they were carvings against a painted backdrop, Hesperia is in the highest relief and her dress in the sharpest detail. Erytheia and Aigle would be carved in a lower relief, with Erytheia perhaps the flattest of all. It strikes me that this is precisely how Michelangelo worked in the Taddei Tondo – which was acquired by the RA in 1829, and so would have been well-known to Leighton. The most ‘finished’ part of the carving is the most important – the baby Jesus, who is in the deepest relief at the centre of the sculpture – a tondo. Even though it is a painting, the same is true of the Manchester Madonna (which was acquired by the National Gallery in 1870, and so easily accessible). The Madonna herself is in the centre in ‘high relief’, with the angels flanking her further back – much as Hesperia is flanked by Erytheia and Aigle. Leighton’s admiration of Michelangelo’s work is widely acknowledged, and is revealed by contemporary photographs of his studio, in which he displayed black and white photographs of the Italian master’s sculptures (I’ll try and hunt some out for Monday). But there is, of course, more to this painting than just the three clear-voiced maidens.

At the top we see the canopy of the tree spreading below the curving frame. The broad, scaly flanks of the serpent loop around the massive trunk, with a last loop and the tip of the tail hanging from one of the slimmer branches on the left. Against the pale sky, which is streaked with clouds coloured a mid-blue in the dull light of dusk, we can see one branch thickly laden with fruit, and there is another, brighter, and clearer, in the foreground at the top right.

If we hadn’t noticed before we can see here that Leighton has accepted the relatively modern interpretation of the ‘Golden Apples’ of the Hesperides which suggests that they were, in fact, oranges. This is clear not only from the shape and colour of the fruits, but also from the leaves, typical of the long, pointed forms of citruses generally. This identification is also true for the garland which circles the frame, made up of bound branches of fruits, leaves and flowers: as ever I am grateful to the Ecologist, who has confirmed that they are accurate depictions of orange blossoms. In the corners of the frame are stylised shells, set against a waving pattern – together these features must surely refer to the island setting of the garden and its surrounding sea.

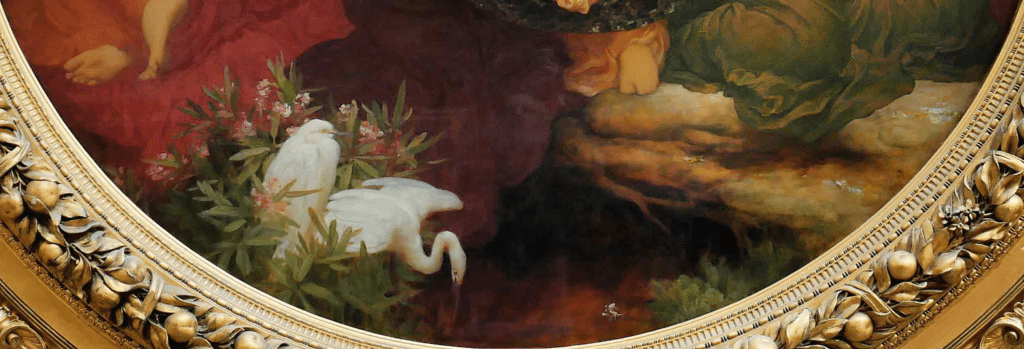

The bottom of the painting also reveals a watery setting – although this must be an inland freshwater pond. Two egrets perch in an oleander bush, one resting, the other alert, with one wing raised, and its neck arched as it scans the water for fish. The still, flat surface of the pond is dark and mysterious, but reveals reflections of the draperies of the Hesperides, interrupted by a few petals of one of the blossoms which are floating just to the right of centre. Aigle’s green drapery falls over a rock which projects out over the water casting a deep shadow. I can’t help seeing an echo of Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks here – the drop at the front of the renaissance painting is rarely commented on, but have another look. This might just be my renaissance ‘heritage’ being over-active, but given the references to Michelangelo, it is not impossible. The Virgin of the Rocks was bought by the Gallery in 1880 and so it is more than likely that Leighton would have known it, particularly given his interest in the art of the time.

In terms of the impact of the painting, the detail at the bottom left is one of the most important. Egrets may be an increasingly common feature of the British landscape, but back in 1892 they would have struck an exotic note. Admittedly, it would probably have been read as ‘oriental’, even if the Hesperides were inhabitants of the occident, towards the setting sun – but it would certainly have served to locate the image as being ‘other’. The implications of the oleander might also be unfamiliar – but, within certain circles, it was a notable feature of the artistic culture of the late 19th Century. Among other references, in 1881 Oscar Wilde opened his poem By the Arno with the lines,

The oleander on the wall

Grows crimson in the dawning light.

In 1865 Matthew Arnold, a friend of Leighton’s, had written Thyrsis, a Monody, which Wilde could well have known: the setting is the same. The poem deals with the premature death and burial of a young poet – a friend of the author’s – in the Arno valley:

(For there thine earth forgetting eyelids keep

The morningless and unawakening sleep

Under the flowery oleanders pale)

The connection between overpowering scents, sleep and death, might change our thoughts about this remarkably sensuous, even decadent painting. The air is heavy with languorous music, the taste of rich wine and somniferous odours: a beautiful and compelling decadence. This aspect of the work is explored more fully in the catalogue of the Leighton House Museum’s 2016-17 exhibition Flaming June: The Making of an Icon, which cites the two poems I have mentioned above – and more. Along with the miniature display currently at the museum, and the Royal Academy’s larger (but still modest) exhibition, the catalogue will be an essential source for my talk on Monday. At the end of the day, though, the most important thing is the painting: Flaming June. Don’t miss this opportunity to see it.

<

div dir=”ltr”>Sadly I can’t make any of the May

LikeLike

Sorry to hear it. Some of the IPTs will be repeated in June…

LikeLike

Dear Richard I have just realised that I inadvertently booked NG05 on the afternoon of 8 May twice, one ticket booked on 5 April and the other on 9 April. I meant to book one ticket for NG05 on 8 May and one for NG06 on the afternoon of 9 May. Is it possible to swap on the the afternoon of 8 May tickets to 9 May? Many apologises Sally Cowan

LikeLike

Thanks, Sally – You should receive an email soon!

LikeLike

I think the original ‘apples’ of the myth were most probably more like quinces than the modern ( Greek) apple. Théy can keep in a bowl for months, and give off a strong but subtle fragrance. Cooking them is difficult as they retain their shape for a long time during the cooking. The ‘marmalade ‘ made from the, was supposed to have healing properties, I remember my grandmother telling me that her mother ( village midwife) would try to get quince paste for women who had had difficult births.

So a fruit worth stealing….

LikeLike

That could well be – thank you!

LikeLike