Vittore Carpaccio, The Dream of St Ursula, 1495. Gallerie Accademia, Venice.

I was in Venice recently for my birthday, and swore I wouldn’t do any ‘work’. It was to be pure pleasure and relaxation. But of course, I’m very lucky, my work is pleasure, and how could I miss an important exhibition like Vittore Carpaccio: Paintings and Drawings in the Doge’s Palace? Added to that, the cycles of paintings that Carpaccio made for different Scuole in the city are some of the greatest pleasures – so I took notes, bought the catalogue, and will report back this Monday, 22 May at 6.00pm. As well as introducing the exhibition, I will also cover other works by Carpaccio that you will be able to see in La Serenissima even after the exhibition has closed. The following week I’ll talk about Lavinia Fontana – there is a superb exhibition at the National Gallery of Ireland – and then The ‘Other’ Vermeers, celebrating the success of the Rijksmuseum’s exhibition (which, by then, will have closed) by looking at the paintings that they could not include. And if you missed my talk on The Ugly Duchess, if you’re quick you could sign up with ARTscapades for the live talk tomorrow (Thursday, 18 May at 6pm), or to catch up with their recording later.

At first glance, this is an image of calm repose. After further investigation, though, it is a little more disquieting, but only until a final analysis does promise peace – a gradual unveiling of depths of meaning which demonstrates Carpaccio’s genius as a storyteller.

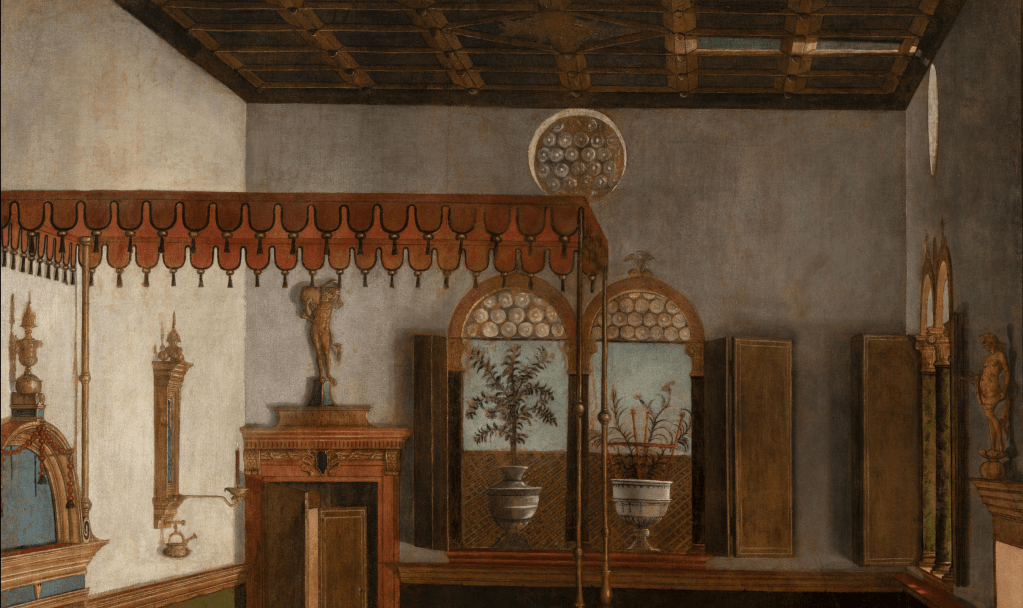

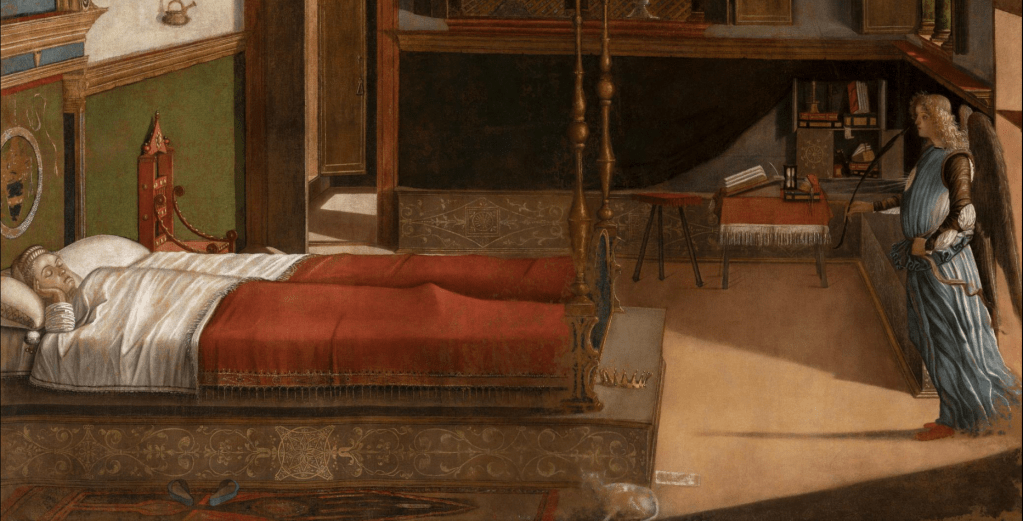

We are in a well-appointed if not overly elaborate room, high-ceilinged, well-proportioned, and brightly illuminated. The front wall has been cut away, revealing a rug lying in front of a four-poster bed, which has a single, sleeping occupant. The shutters and doors are open, and a second character enters the room, together with what we can only assume is the light of a fresh dawn, illuminating the floor and brightening the opposite wall.

The ceiling is coffered, with square frames of wood projecting below flat fields which have been painted blue, as if it were the sky seen through a trellis. The back and right walls both have circular windows set into them, and we can see that the one ‘opposite’ uses bullseye glass – the central sections of hand-spun sheets of glass – which allow for illumination but not clear vision. At that height it would not be important to see out anyway. The circular window to the right has light shining through it from below. The exact angle could easily be measured from the way it lights up a section of the ceiling. The precision with which it illuminates two of the coffers – no more, no less – suggests to me that Carpaccio was thinking of some kind of order, presumably divine. The angle of the light confirms the suspicion that the sun is low, and that this is early in the morning (unless, of course, the princess has taken an afternoon nap). There is a certain symmetry in the arrangement of the walls, although it is hard to tell how similar they actually are. However, we can see that each wall has a door with a statue above it, and a pair of windows, the frames made up of green marble columns supporting semi-circular arched tops. The lower, rectangular sections have shutters, which are open, and there is more bullseye glass in the semicircles formed by the round arches. The bedhead also has a semi-circular top – a segmental pediment above an entablature, an idea derived, like the frames of the windows, from the classical language of architecture. The canopy of the bed is covered with a red cloth, fringed with rounded and be-tasselled pennants. It is like the canopy you would find above a throne, and speaks of the royalty of the bed’s occupant. In other ways it is not perfect as a four-poster bed: there are no curtains to provide privacy or maintain warmth. Its design is presumably intended more for clarity, and to allow our understanding of the room and its contents. It certainly allows us to see the door at the back of the room, and the wall to the left.

The door frame is carved with elaborate detail, speaking of considerable wealth. Through it we see a smaller room, with another open window. It is a dressing room or similar, presumably. Above the door is a sculpture of a naked man carrying something. Undoubtedly, like the architectural elements, this is another classical reference. It is usually identified as representing Hercules: that could be a tail projecting to the right, which would belong to the skin of the Nemean lion – but this is by no means certain. What can be identified, although not seen clearly, is the subject of the painting on the left wall. It has a gold frame, and a gold background, and depicts a blue form which takes up most of the picture, although a little less towards the top: it is the Virgin Mary. Despite the pagan references, we are in a Christian household. A lit candle, which has presumably been burning all night, stands in front of the painting on a projecting candelabrum, and a bowl hangs below. The object projecting from it is presumably an aspergillum, the object used to sprinkle holy water: this is a sacred space.

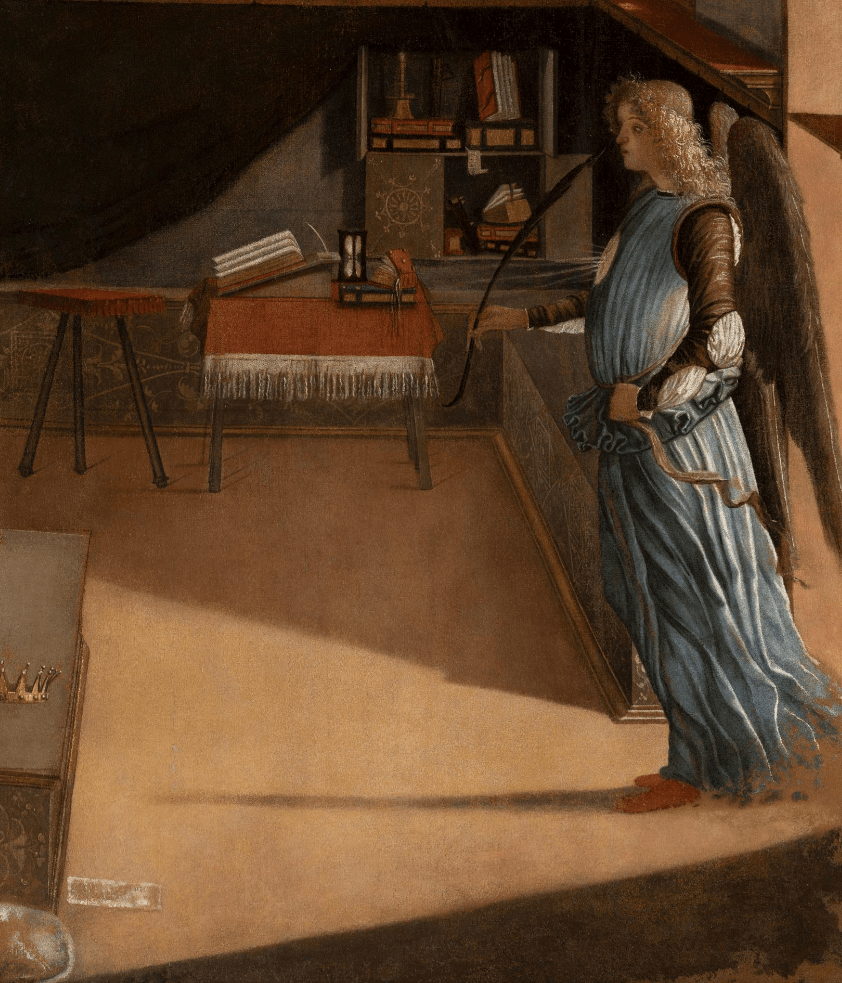

The sanctity of the scene is confirmed by the nature of the visitor – the winged visitor – an angel. As he steps through the door the light also enters the room, spreading out across the floor as far as the doorway at the back left. He looks towards the princess in the bed, sleeping soundly, who lies on her back with her feet towards the door, effectively aligned with her heavenly guest. The room has a high wainscot, topped by a classical cornice, and hung with a pea-green cloth.

In the back right corner the green hanging has been lifted to reveal a cupboard with open doors, containing books and a candlestick. On a table just in front of it are further appurtenances of a scholar: more books, an hourglass, and the thin white curve of a quill pen sitting in an ink well. It seems odd that the cupboards would usually be hidden behind a cloth, but perhaps this is because the implied level of scholarship would not normally be expected of a young lady. But then, she is no normal young lady. There are apparently more books resting on the cornice behind the angel’s head, and, to our right of the door, the cornice closer to us projects over the brightly lit doorframe, pointing to the angel, and framing his wings, at roughly the level where the light catches the golden hair at the back of his head. Light streams through the door behind him, yes, but it also emanates from a patch on his chest, glowing white through the blue of his tunic, drawing our attention towards – as if we hadn’t noticed it before – the palm leaf he is holding in his right hand. The palm is a symbol of victory, and here it is a symbol of victory over death. The princess is Saint Ursula, Virgin Martyr, and she is destined to die: she is currently dreaming of her death.

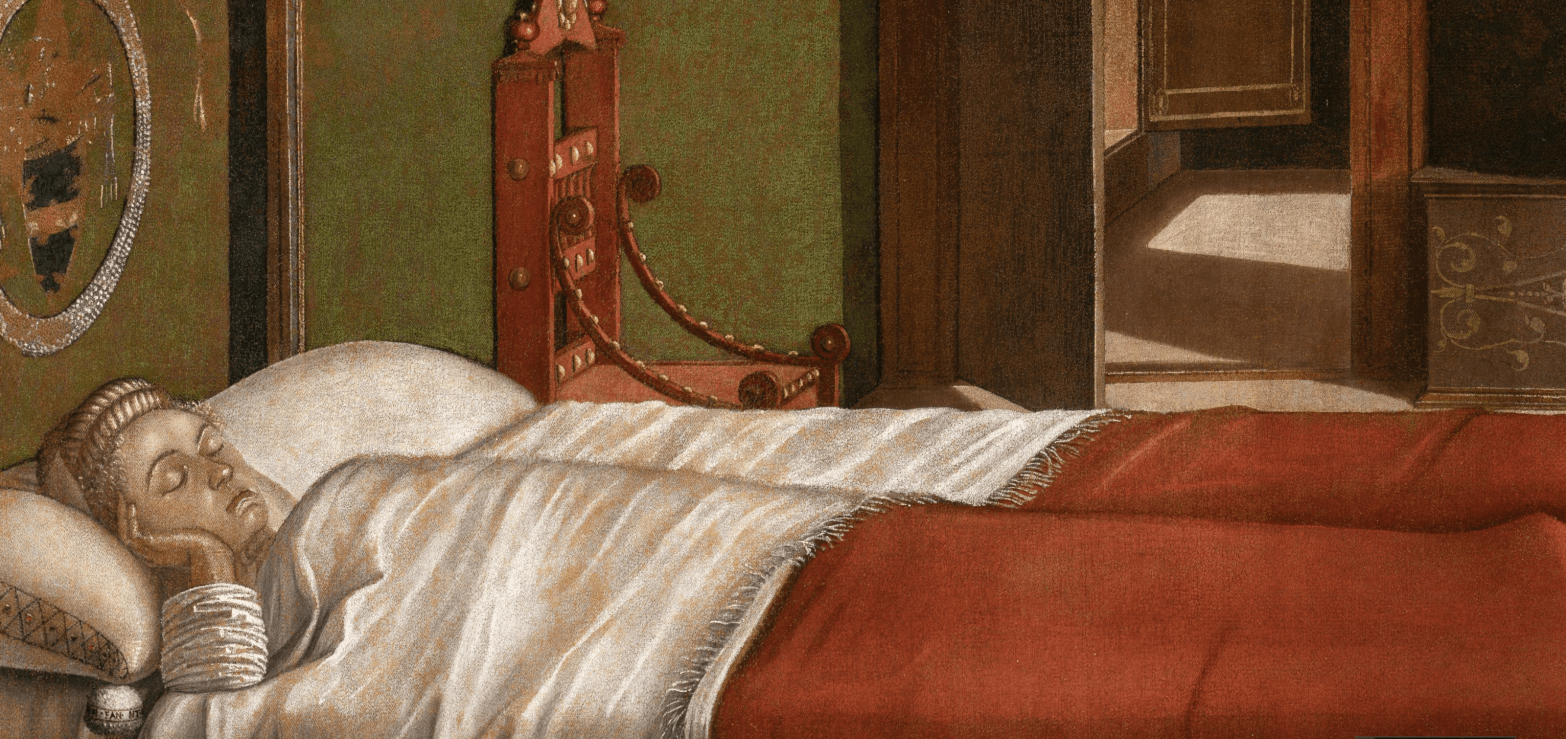

Only those of the highest status would have a carpet on the floor – with the exception of the Arnolfini, who have bold pretensions – and it is most commonly seen in paintings under the feet of the Virgin Mary, in front of her throne as Queen of Heaven, on occasions when she is sitting under a canopy very much like the one above this bed. With both canopy and carpet, Ursula is depicted as a Virgin Princess of Heaven. As a good girl, she has taken off her slippers – they are blue – and has left them on the carpet in front of the bed. As a good princess, she has taken off her crown, and set it on the step at the foot of the bed. Her cat sits nearby. Or is it a dog? There are similar dogs in other paintings by Carpaccio. It’s hard to tell, the painting is sadly worn – another victim being the small cartellino, the scrap of paper above the pet, which originally bore Carpaccio’s signature. In the background we see the light from the door on the right reaching through the door at the back left. But… wait a moment…

The light from the door on the right emerges from behind the red bedspread and crosses the threshold of the back room. In that room another window is open, or it could be a door, with a step leading out. There is light shining through that open door or window, and it is shining from left to right. The light which enters with the angel shines from right to left. Only one of these can be the light of the sun, and, let’s face it, it must be the light in the back room. The low angled light on the ceiling, the light which announces the angle, and flows into the room with him, must be the Light of God. Ursula will awake to a new day, yes, and it is the light in the back room which shows us that. The light in the foreground also signals a new dawn – a symbolic one – which is also a new life. The princess is dreaming of her death, and yet she sleeps with perfect repose, calm and untroubled, her cheek nestled in her right palm. There is no peace for the wicked, it is said, but her peace is perfect: she is as far from wicked as you can get. Why should she be troubled? Why should the news of her death concern her? She knows that she is going to Heaven, and will go straight there: the palm of victory over death is hers for the taking. Her crown, the crown she has placed so carefully at the foot of the bed, sits precisely between her and the angel: the God-given crown of her father’s earthly kingdom (if we believe, as people did, in the Divine Right of Kings) is also her heavenly crown.

Remarkable as the intricacy and complexity of the storytelling is in The Dream of St Ursula, this is only one of the paintings from a cycle dedicated to her life, and that is only one of the cycles which Carpaccio painted, either on his own (if with the collaboration of his workshop), or as part of another team. There are also drawings associated with it, and with the myriad of other paintings which stood alone. We will look at the very best of it on Monday.

So, this is the angel come to take her spirit? Is that how it is to be read?

LikeLike

No, it’s a dream, telling her that she will die… there are a couple more paintings to go in the cycle!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Richard,

Damn â I am out on Monday, but hopefully can watch next Monday. I just wanted to say that I loved your half-time talk on NGâs 1700=1800, which I caught just now. You treat us as intelligent. Just thought: Rosalba Carrieraâs splendid portraits of Horace Walpole and Henry Pelham-Clinton: nice to see them again. Yes, Thomas Gray: from my reading of it all I think Gray was in love with Walpole (well, of course) and the quarrel was because Walpole had an affair with someone else while in Italy, presumably Pelham-Clinton. I canât remember. Poor Gray â Walpole never slept with him.

Hope to catch your next lecture!

Best wishes,

Monica Kendall

Sent from Mail for Windows

LikeLike

Thanks, Monica! Food for thought… I should do some more research, I suppose, but in some ways it is tangential to the images.

LikeLike

I am not criticising at all! You were right about the class, I am sure. And poor Gray was rather ugly. I remembered something from Robert L. Mackâs biography of Gray. But I donât think he connects it with Rosalba Carrieraâs portraits. She is not in the Index. It was a vague memory from reading that biography and thinking that Iâd be furious about the two similar shirts. She was a clever woman to detect something going on between the two men ….

Monica

Sent from Mail for Windows

LikeLike

Hi Richard

Yes, the Lavinia Fontana exhibition currently running at the National Gallery of Ireland is indeed superb.

Also, great credit to the curator of the exhibition Dr. Aoife Brady and her wonderful companion book “Lavinia Fontana, Trailblazer, Rule Breaker”

Have a great day.

Fiona Marshall

LikeLike

Indeed- the book is currently sitting on my desk!

LikeLike