Gwen John, A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris, c. 1907-9. Sheffield Museums Trust.

When I saw the subject of today’s post in the exhibition Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris (about which I will be talking this Monday, 14 August at 6pm), it seemed remarkably familiar to me – there was a feeling in the back of my mind that I had lived with it for some long time. And yet, the label of the painting told me that it belonged to the Sheffield Museums, and although I have been to Sheffield, and have visited one of the museums, I can’t say I remember seeing Gwen John’s work. So I want to look at this painting today not only because I think it’s beautiful, but also because its familiarity is something of a mystery. Maybe the ‘familiarity’ is part of the painting itself. The talk will be the second in my series An Elemental August: different vistas. As I said on Monday, in trying to slot these four artists into my Art Historian’s title, I have finally decided that Lucie Rie should be associated with Fire – because of the kiln – and that Gwen John will represent Air – there is certainly an ethereal, airy quality about today’s work. They will be followed by Evelyn de Morgan on 21 August, who I’m associating with Water, because of the fluidity of her style, and then, to close the series, Paula Rego (28 August). The National Gallery’s small exhibition, which opened recently, is a celebration of her mural Crivelli’s Garden – and ‘garden’ implies Earth. This has both practical and metaphorical senses, I think: major themes of the mural are nurturing and nourishing. As ever, you can find more details via these blue links or in the diary.

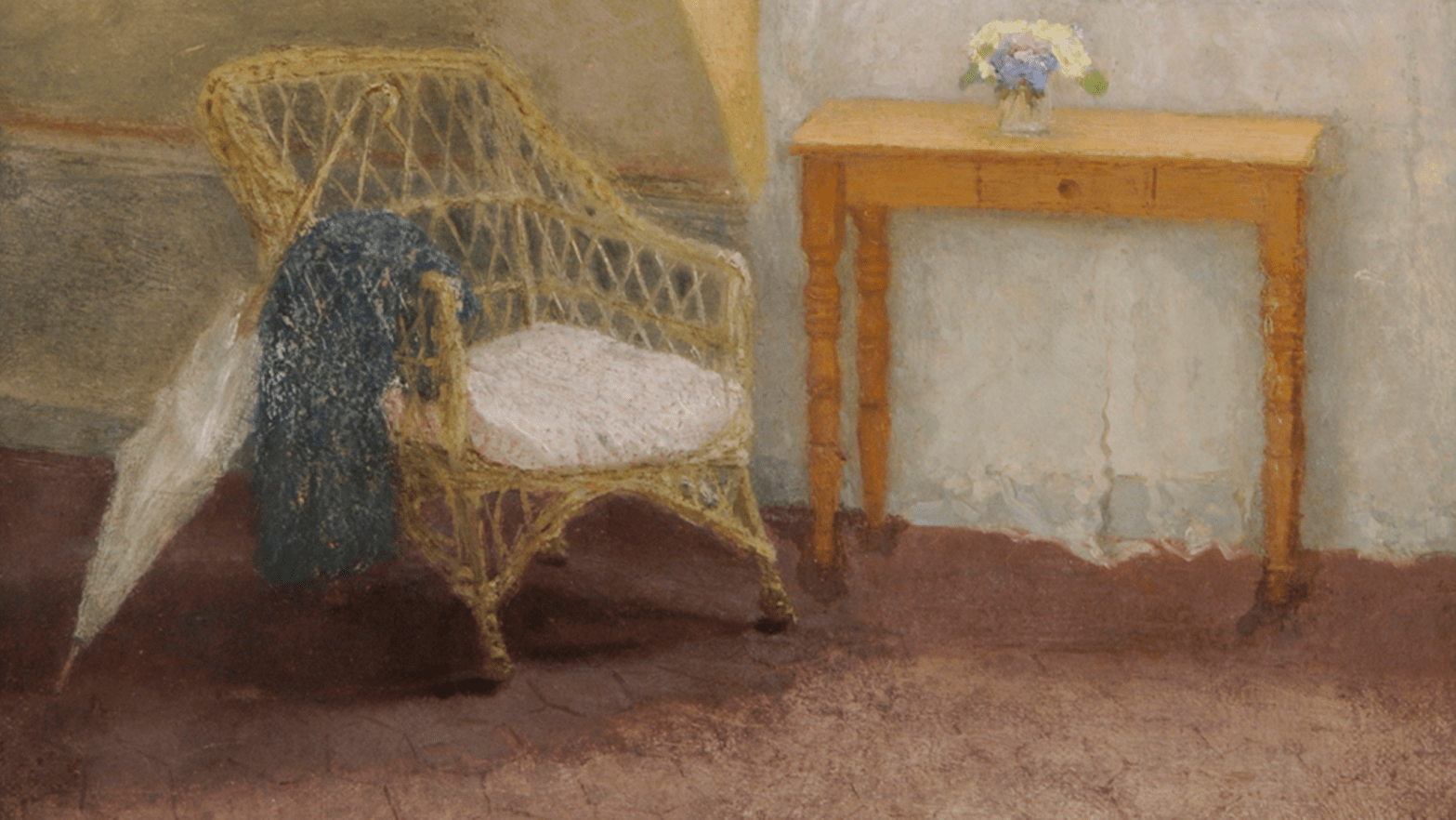

There isn’t much to this painting, you might think – a chair and a table next to a window in an otherwise empty room. But I should remind you – and I know that you know this – that the experience of seeing a painting in real life is very different to what you see in a reproduction. On your screen it might look like an illustration to a blog post, but when seen in the flesh it is very different. Not a large painting, but almost certainly larger than you will see it now (31.7 x 26.7 cm – a bit larger than an A4 sheet of paper), it is far more subtle than colour reproduction allows. It has a mesmerising presence, almost hypnotic.

Gwen John had an uncanny knack for painting the everyday world. Everything seems normal, everything seems real, and yet her perceptive gaze and her focussed sense of composition, combined with an ability to identify and reproduce subtle differences in tone and colour, render the banal significant. For all the world this looks as if we have opened the door to her room and found it empty, the chair, table, and associated objects exactly where they had been left by chance. But, of course, nothing could be further from the truth. In the brilliantly researched, written and readable book which accompanies the exhibition, author and curator Alicia Foster quotes Ida Nettleship, John’s friend and soon-to-be sister-in-law, writing to her mother in 1898, the year they both graduated from the Slade School of Art: ‘Gwen John is sitting before a mirror carefully posing herself. She has been at it for half an hour. It is for an “interior”’. If she could spend at least half an hour posing herself, how long would she take arranging the furniture? This may be an Interior, and yet it takes on the qualities of a Still Life – while still looking entirely spontaneous.

As far as I can tell – judging from the digital file on the Sheffield Museums’ website at least – this is, almost exactly, the top half of the painting. This ‘half’ is divided in two again, with the vertical between ceiling/wall and window cutting the painting more or less down the central axis. This is a dormer window: we are in the attic, which might have a connection to the romantic notion of starving artists eking out a meagre existence, especially as we are in Paris, if it weren’t for the fact that, even in this apparently empty detail, there is no evidence of poverty. All is clean and tidy, whether it is the cream-coloured wallpaper or the crisp, white curtains. Seen like this, the top half of the Interior could almost be an abstract in its own right, with one rectangle divided by a diagonal line into darker and lighter quadrilaterals, and another, equally sized rectangle, divided further into four equal rectangles in various shades of pale grey. However, this is, of course, a window, with a net curtain acting as a veil, while still revealing the buildings opposite. The muted, mottled greys, so close in tone as to be almost indistinguishable, are reminiscent of the work of Vilhelm Hammershøi, sometimes called ‘the Danish Vermeer’, and it is indeed possible that John was familiar with his work. The Nettleships – Ida’s family – knew the artist himself, and saw him when he came to London. As Gwen kept up her acquaintance with the rest of the family even after Ida’s untimely death in 1907, it is just about possible that she too might have met him.

You could argue that there is far more to look at in the bottom half of the painting – although there’s still not much. A wicker chair with the palest of pink cushions is subtly angled away from a small side table. A parasol leans against the arm of the chair, next to some blue fabric, which is presumably some form of garment – although the blue shape seems more important that what it actually represents. A lightweight jacket, maybe, to be worn in the sun, when heading out with the parasol? On the table is a small vase containing blue, yellow and pink flowers, and a few fresh green leaves. The floor appears to be made of hexagonal brick-red tiles.

The flowers form the brightest patch of colour in the painting. If you really wanted to, you could suggest that the rose pink, primrose yellow and sky blue flowers represent highly unsaturated versions of the three primary colours, red, yellow and blue, and as such might speak of the art of painting itself – but I think that this is is coincidental. What I do find interesting, though, is that the vase is placed, as everything else appears to be, haphazardly. It sits above the central drawer, halfway between the knob and the drawer’s left edge. Hammershøi, in a painting included in the Pallant House exhibition (which I will show you on Monday), depicts a more formal interior, with everything arranged symmetrically. His is just one of several paintings chosen to illustrate the work of artists with whom Gwen John had interests in common. I may be biased, but John always seems to come out of the comparison well, her paintings far ‘better’ than those of her more famous (male) contemporaries in my opinion (although the Hammershøi is superb).

I really enjoy her use of negative space in the detail above. The wicker chair is placed so that one of its legs lines up with the two left legs of the side table, the three feet being equally spaced along a diagonal. The arm of the chair scoops under the sloping ceiling, and then the leg curves down towards the table, leaving the cream- or even butter-coloured eaves projecting at a right angle into the space between the table and chair: conversations like this between the elements of a composition always please me.

Returning to the picture as a whole, the table and chair look far smaller in their context: this is a large room, rather than a cramped attic (if one were making assumptions). The light from the window brightens the floor, which is cast into shadow around, and especially under, the chair. This broad, lighter area of flooring makes clear something which we might not otherwise have registered explicitly: there is nobody there. The light bounces off the pale cushion making it clearly visible, thus making an equivalent statement: no one is sitting down. Nor is anyone holding the equally visible, light parasol – there is not even anyone to pick it up. The chair has been turned out to face the empty space, and under the table we see the net curtains, which fall to the ground and part in the centre. Being able to see them clearly like this reminds us yet again that no one is getting in the way. This is absence made present. The lack of a humanity might imply that this is a sad painting, speaking of loneliness and isolation, but not so: the bright, clear, fresh colours of the flowers and the light from the window – the luminous curtains – lift the mood towards an enlightened clarity, and purposeful simplicity, a life that is ordered, balanced, and in control. Notice how the diagonal of the parasol mirrors the downward angle of the ceiling, with the diamonds formed by the overlapping diagonals of the wickerwork echoing this theme. Gwen John is showing us her room, the room in which she was free to do whatsoever she pleased, where she could entertain whomsoever she liked, without criticism, and where she could relax and be herself after the everyday performance of appearing in public. As Virginia Woolf would write in her influential book, A Room of One’s Own was what a woman needed to become a writer. That was published in 1929, but two decades earlier, when this Interior was painted, Gwen John already knew what she needed to be a painter. She is not cut off from the outside world, though – the curtains may be a veil, but the world is still visible, and the parasol and flowers tell us that she both goes out and comes back in. Far from being the shrinking violet of myth, she was a determined woman who knew what she needed in order to succeed in her chosen profession.

However, none of this explains why this painting should have seemed so familiar to me. I suspect that it could be a feature of the painting itself. The naturalistic, and yet unnervingly perceptive observation of everyday details that gives you a direct connection to what you see means that it is already ‘familiar’, while the subtle shifts of tone and colour which make the different parts of the composition look like the others, and yet not quite the same, must add towards this sense. The echoes of forms, and angles, and lines work like rhymes in poetry: when they hit home it feels like you have arrived, and, although unaware of the fact, give you the sense that you always knew where you were going. I suspect it is something akin to déjà vu. You see something, and it instantly forms a memory. But you are still looking, and so already what you see is familiar, yet the memory was formed so quickly that you can’t pin it down, and it seems like it has always been with you. It’s either that, or something more personal.

Last week I mentioned that I had originally planned on becoming a theoretical physicist, but in my second year as an undergraduate my focus turned to geology. By my third year, I had realised that I wasn’t going to be a scientist at all, and should try something new. That is when I stumbled upon the History of Art. As a hungry student of a new subject I was influenced by Jim Ede and Kettle’s Yard, not only developing an admiration of Lucie Rie, but also trying to live as Ede had done, including placing images in interesting and unexpected places. For a year or so one of those images was a postcard from the Fitzwilliam Museum of a painting by an artist a friend had spoken enthusiastically about, the older sister of a reprobate brute of a painter. The sister’s work was far superior, I was told, and showed far great delicacy and artistry. It was, of course, Gwen John, and my thoughts about her and her brother Augustus have not really changed much in the ensuing decades (an idea I will illustrate – briefly – on Monday). My post card lay flat on a small, circular table given to me by my sister. It showed a woman seated in the same wickerwork chair next to a low circular table on which were placed a brown teapot and a rose-pink teacup – the same technique of lifting the whole mood of a painting with a little hint of clear, bright colour. Next to the post card I had a small vase made by the same potter as the dish I mentioned last week, in which I arranged flowers – pinks – of exactly the same hue as the teacup in the painting. I was lucky enough to be living in the Old Court of Clare College, Cambridge, and visible above the other side of the courtyard was the roof of King’s College Chapel. Being on the top floor, in order to see it I had to look out through a dormer window. In Pallant House the painting I had a post card of – The Convalescent – is currently displayed not far from today’s Interior, but it turns out that I didn’t know the Interior at all. It just reminded me of my own room.

August 14?

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Yes?

LikeLike

You’re so right. Months/Years… they pass me by. But the ‘event’ itself is dated correctly, at least! Thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks, I look forward to it. Should have been clearer about the date but I figured the link would bring us to the right one. Hammershøi and Elinga did come to mind when I saw Gwen John’s painting. Hammershøi is one of my favorite artists.

LikeLike

Hammershoi is great – and the one they have in Chichester is a superb example. I have seen paintings by Elinga, but am not familiar with his work – in my mind it tends to blend in to Pieter de Hooch, I’m afraid!

LikeLike

Beautiful Richard and very timely as we’re going to see the exhibition tomorrow! I will look at this painting with new appreciation, thank you. ( BTW, is there a typo? I assume the date of your talk is August 14th?

LikeLike

Enjoy – it’s very cleverly hung: John’s work takes over as she takes control – and the book is superb. And yes, a typo… now corrected, thank you (but still with the original mistake for those getting it by email…)

LikeLike

Love this painting and it’s complex simplicity, if I can say that? It also reminds me of my attic bedroom many years ago when I was a very young girl living in Wales.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You can indeed say that!

LikeLike

Good morning Richard Is the talk on Monday 14th August on Zoom being recorded? Thank you Elizabeth

Sent from Mailhttps://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?LinkId=550986 for Windows

LikeLike

I’m afraid not, sorry – I try and remember to mention this on every description, but forgot to on this particular occasion – apologies.

LikeLike

Have you read Margaret Forster’s “Keeping the World Away”, which is a fictional history of this painting and its owners? Just wondered if that could be why it seems familiar.

Also, there’s another version of it held by Museum Wales in Cardiff. I loved the book, decided that I must see the painting – and discovered that it resided two miles down the road at Sheffield’s Graves Gallery! I’m looking forward to seeing it in Chichester next month.

LikeLike

I haven’t read it, I’m afraid, nor had I heard of it – so thank you! I’m always intrigued by fiction inspired by art, but sadly I rarely enjoy it as it is all too often ‘wrong’ in terms of technique or intent – but a fictional history of a painting sound more interesting.

The version in Wales is a fascinating comparison, with the window open, and a book – also open – on the table. The view doesn’t look like any part of Paris that I know (not that it’s a city I’m intimate with), nor does it look like the other John interiors which were painted in Paris – I wonder if it is misnamed, and is actually her home in Meudon? Alicia Foster doesn’t comment on what is outside the window, so I should read more widely, or track down the locations!

Do enjoy the exhibition – I found it very rewarding.

LikeLike

…having said that, I’ve just checked, and a caption in the exhibition gives a precise address, and I can see that there is a notable garden nearby!

LikeLike

Am three-quarters of the way through Alicia Foster’s biography of John’s life in London and Paris. The chapter “The Modern Interior” is excellent in discussing the two paintings of the Artist’s Room. I saw the exhibition in July and can’t now remember if the painting with window open was in it. Age catching up with me!

LikeLike

It’s not age… when there are variations like that it’s very easy to imagine a painting was there, or to forget if it was or not – but it isn’t there. I think the book is superb, so thoroughly researched, so well written, and so readable! Having said that, the chapter on interiors is oddly placed – while trying to fit Gwen John’s thematic interests into her chronology this one gets oddly left behind. But that’s a minor point.

LikeLike