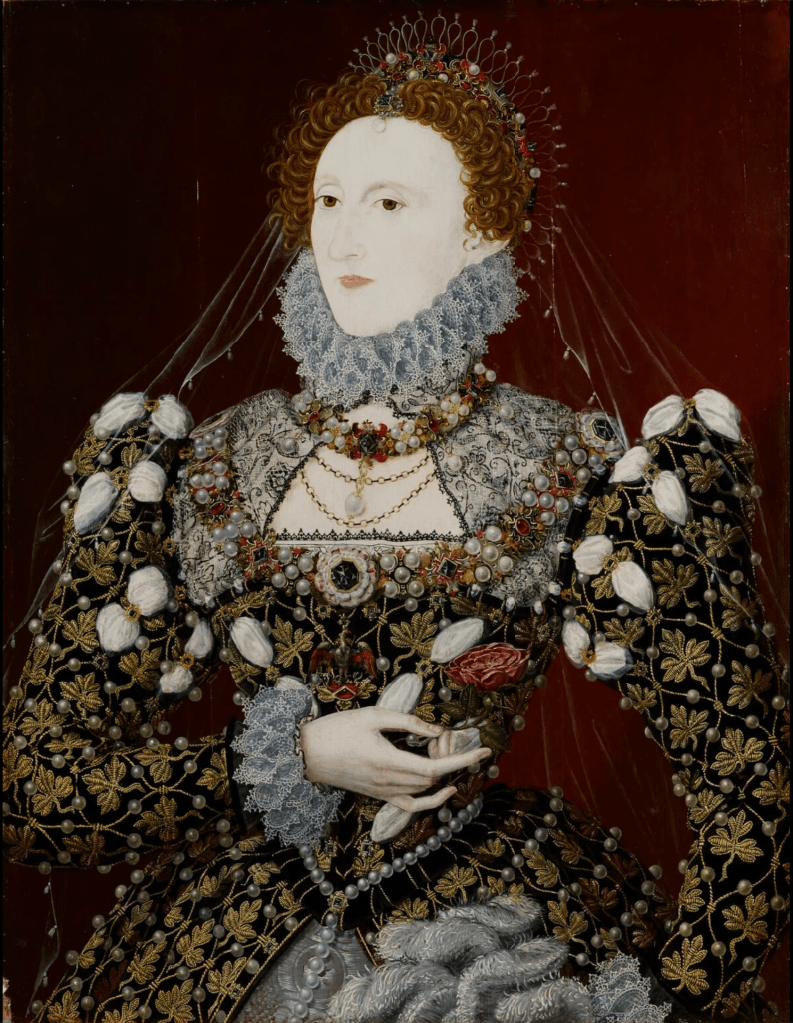

Nicholas Hilliard, Queen Elizabeth I, about 1575. National Portrait Gallery, London.

After an enjoyable stroll around the first half of Room 1 at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool earlier this week (thank you to all those who came!), I’m looking forward to returning for (The High) Renaissance Rediscovered this Monday, 19 February at 6pm, looking at the 16th Century works, including Elizabeth I’s twin – or at least, the twin of the portrait I want to think about today – not to mention a fantastic image of her father, Henry VIII, and paintings by Cranach, Titian, and Michelangelo (possibly) among others. On 26 February I will introduce the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery’s highly praised exhibition Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement which has been a huge success in the USA and heralds the re-opening of the museum after what is beginning to seem like the obligatory refurbishment. The exhibition has a lot in common with Sargent and Fashion, my talk about which will follow on 4 March: rich colours and fabulous frocks for a start. And talking of fabulous frocks…

Detailed accounts were kept of the Royal Wardrobe during the reign of Elizabeth I, and after her death over 2000 gowns were recorded. That’s a different gown every day for five and a half years! This was surely one of the most elaborate, with puffed sleeves slashed and inserts sewn in to imply a white chemise (and there would have been a real one underneath), together with insistent embroidery in gold thread, patterned as a knotted net framing trefoils. There are also a lace ruff and cuffs, pearls, a jewelled necklace and collar, yet more jewels and a fan. However, despite this excess, the overall image is one of magnificence, and of dignity, implied not only by the Queen’s demeanour, but also by the deep red background, additionally conveying royalty and wealth. Elizabeth remains aloof: concerned with affairs of state but in control, a person we must admire, but might fear to approach.

Her red hair is tightly curled around her high forehead (the latter a sign of beauty in the 15th and 16th centuries), mimicking the looping edges of the impossibly delicate (and delicately painted) headdress, from which a diaphanous veil hangs, spreading down behind her neck and over her shoulders. The headdress echoes the form of a crown – she is Queen, after all – but also of a halo: here and elsewhere the artist is subtly playing on the imagery of the Catholic Church. Although Elizabeth was Protestant, she was keen on some aspects of Catholic worship: singing, for example – and in this she could be seen as responsible for the great English tradition of church music. Her face is pale, without a mark, you could even say ‘immaculate’ (which might tell you where we are going…), this pallor and perfection speaking of her famed virginity – which, whether historical fact or convenient fiction, remained her official status.

It is this face which helps confirm the identity of the artist. On the left is a detail from a miniature by Nicholas Hilliard, also from the National Portrait Gallery. The pattern for the face is the same, and so is the depiction of tight curls around the forehead, each hair painted individually and wound in spirals of brown, butterscotch and cream. The intricate details are painted in the same stylised, diagrammatic style which helps to define Hilliard’s oeuvre. There is a difference in appearance though, which is hardly surprising given that the miniature measures a mere 5.1 x 4.8 cm, as opposed to the oil painting, which is 78.7 x 61 cm. Technical analysis reveals that, in the oil painting, the eyes, nose and mouth were originally lower – suggesting that Hilliard altered his plans once he had started painting. This suggests this is an autograph work, and the original: copyists tend not to change their minds. Even though he is famed for his miniatures, it is known that Hilliard also painted in oils. He also wrote, and says that one of his miniatures – maybe this one – was painted outside, the Queen sitting for him in a garden. He explained that she didn’t like shadows in her portraits: the diffuse outdoor lighting would have helped him to realise this. Why didn’t she want shadows? Well, they would have shown her age. As we have seen, there isn’t a mark on her face, not even the finest wrinkle. By 1575, when this was probably painted, she would have been 42 – getting on a bit, for the 16th Century.

The ruff is tightly wound, like her hair, and is regular, like the headdress. It speaks of the same profusion, order and attention to detail. Her necklace – with groups of four pearls alternating with richly set jewels – is a more elaborate version of one worn by Elizabeth’s stepmother, Jane Seymour (see 211 – Hans Holbein: the other side of the mural?). The chain, or collar, which hangs from her shoulders, although an elaboration of the pearl-and-jewel motif, is also similar to that worn by her father in the Whitehall Mural (see 207 – Making a Monarch…), not to mention the portrait at the Walker which we will look at on Monday. By echoing Henry VIII’s choice in jewellery she is making some sort of claim for the continuation of the Tudor dynasty. The puffed sleeves, too, echo Henry’s padded shoulders, while the layering of clothes – especially when combined with the slashing – speaks of a similar wealth of materials. But I wonder if these puffs of chemise have another implication?

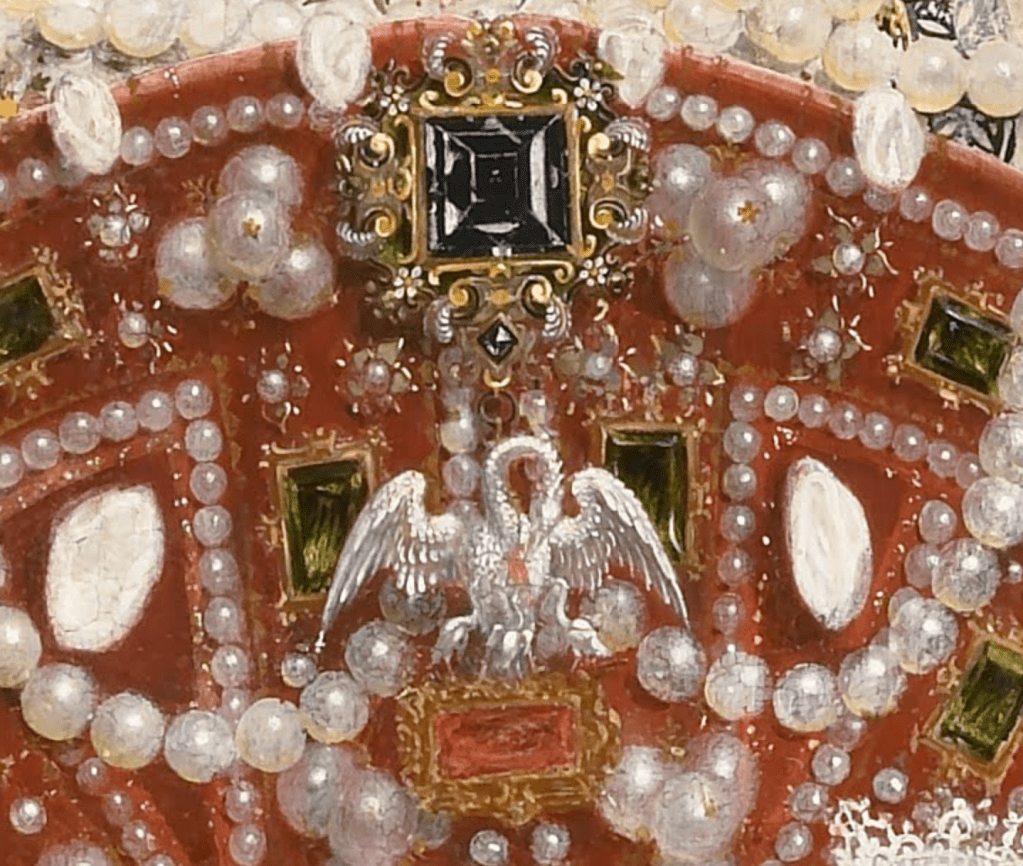

A red rose is held delicately between the thumb and middle finger of her right hand. It is said to refer to the Tudor dynasty, but the red rose was the symbol of the House of Lancaster: to be a true Tudor rose, it should be combined with the white of the House of York. Am I right in seeing the placing of the rose next to one of the white puffs of undershirt as not entirely coincidental? The oval form of the white fabric is similar to the foreshortened top of the rose. Together, maybe, they imply the combination of the two houses, the stock from which the Tudor rose will be bred. Or am I seeing things? What is clearly visible, though, is the insistent patterning of the gown with the gold embroidery, regularly elaborated with pearls, which also form a slim belt and ‘chain’. The regularly looping cuffs have the same form as the ruff, and this is echoed by top of an ostrich feather fan. Just above the hand, pinned to Elizabeth’s chest, is the jewel which gives this painting its name, ‘The Phoenix Portrait’.

The myth of the phoenix is well known, although ancient in origin: there is only ever one, and it lives for many years. At the end of its life it is consumed by flames, and reborn from the ashes. As such, in Christian mythology, it becomes a symbol of Christ’s death and resurrection. The flames can also be seen as purifying, and so it also becomes a symbol of purity and regeneration. Elizabeth I, as Queen, had a problem: how could the monarch marry a man? In a Christian marriage (and many others, I’m sure) until relatively recently, the wife was supposed to be subject to her husband. But how could the Queen be subject to one of her own subjects? It wouldn’t make sense. The only solution would be to find someone of the equivalent rank – which would mean a marrying a foreign King, or, at least, the heir to a throne (as her elder half-sister Mary had). With this came the inevitable risk that the rule of the country might pass out of English hands. Hence her choice: to remain the Virgin Queen. But that implied that the Tudor dynasty would not continue. However, if Elizabeth were like the Phoenix, she could remain pure, and virginal, and yet the dynasty would be regenerated. Precisely by what means was not made clear, but increasingly in the 1570s – when this portrait was painted – Elizabeth became associated with the Phoenix.

There are also other associations at play here. There were other virgin queens, after all. Or rather, one other: Mary, the Virgin Queen of Heaven. One of the many epithets applied to Mary was Rosa Senza Spina – ‘a rose without thorns’ – the beauty without the results of sin: immaculate. As well as its link to the Tudors, the rose which Elizabeth holds can also remind us of Mary. After all, we have already noted that Elizabeth has the hint of a halo: in some respects her image would have replaced that of the Virgin Mary in the popular imagination, she becomes the mother of us all. The Phoenix brooch was not Elizabeth’s only jewel, of course – with over 2000 gowns, there must have been many more.

Compare these two, for example. The phoenix brooch is on the right, and on the left is another, very similar in format: a bird with raised wings and a neck bent down to our right. However, its colour and behaviour are different: it is a Christian symbol called ‘the pelican in her piety’. It was a widely held belief that pelicans pecked at their own breasts and fed their young with their blood – a misunderstanding that might have arisen from seeing a pelican preening its chest feathers. It became a symbol of Jesus’s sacrifice – particularly given the bleeding wound in his chest. Worn by Elizabeth, it represents her sacrifice, giving her life for her country and her subjects. It also presents her as a mother to the nation. The pelican brooch is a detail from a remarkably similar portrait, the one held by the Walker Art Gallery.

Although the gowns are different, the portraits are otherwise effectively mirror images. Indeed, a tracing of one of the faces can be matched exactly to the other. As the Phoenix Portrait was altered during its creation, it makes sense to suggest that it was painted first, and a tracing was used by Hilliard – or his workshop – in order to start work on the Pelican. Stylistically, too, it seems clear that they are from the same workshop – and that’s not all. Dendrochronology (used to date paintings by comparing the tree rings visible in the wooden panels) has revealed that both panels were made from the wood of two different oak trees. However, both use wood from the same two trees, which confirms – as if the elaborate depictions and mirrored faces did not – that the two portraits have a common origin. They are true twins. There is plenty more to say about the Pelican Portrait – but I shall leave that until Monday.

<

div dir=”ltr”>Once more I’m delighted to read your weekly post …….. & after the live Zooms I’m always pleased to “go” to the exhibitions which

LikeLike

I’m so glad, Moira – thank you!

LikeLike