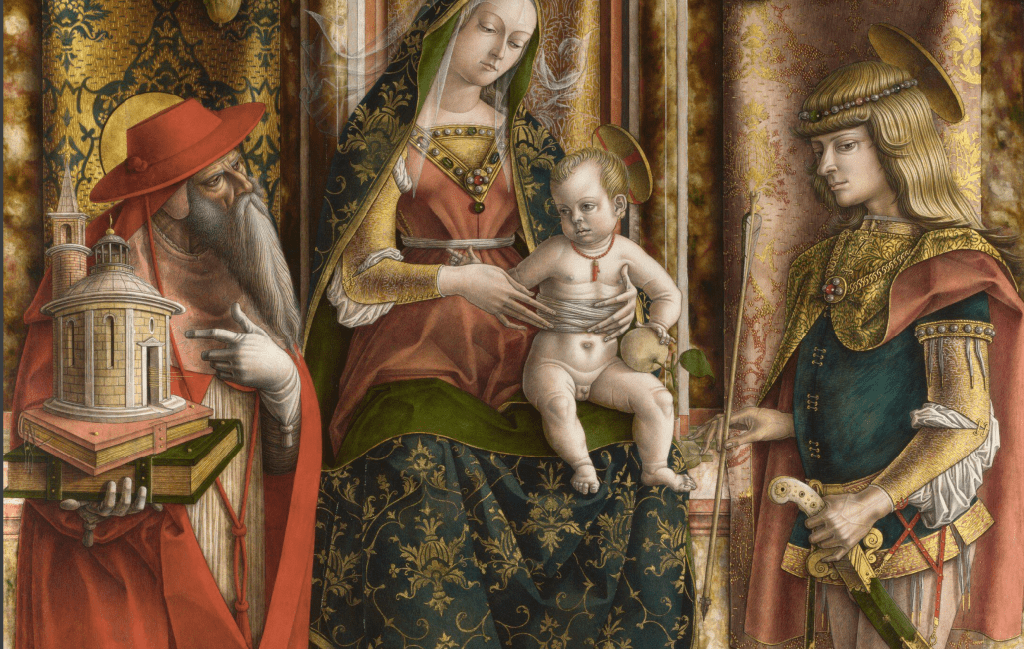

Carlo Crivelli, La Madonna della Rondine, after 1490. The National Gallery, London.

The National Gallery’s exhibition Paula Rego: Crivelli’s Garden, which I will be talking about this Monday, 28 August at 6pm, celebrates the painting which the late, great Portuguese-born artist created for the dining room in the Sainsbury Wing when it was opened back in 1991, a project relating to her position as the gallery’s first Associate Artist. I will discuss the painting in depth, looking at its origins and its relationship to both the National Gallery’s collection and to Rego’s life and work. Although influenced by many different paintings and life experiences, the composition, on three large-scale canvasses, was inspired by a very specific altarpiece by one of my favourite artists – or rather, by part of that painting – so I thought it would be a good idea to look it today. Paula Rego will bring my Elemental August to a close, giving way to what promises to be a somewhat Scottish September. This will start with A Couple of Couples: Charles Rennie and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh on 4 September, and then James McNeill Whistler and Beatrix Birnie Philip on 11 September – the University of Glasgow has some of the best holdings of all four artists in their collection. The following week I will be in Scotland itself, visiting Glasgow for five days with Artemisia (there are still one or two places available if you’re interested: see the diary for more details, and please do mention me if you sign up), and the month will conclude on 25 September with The Fleming Collection’s superb exhibition Scottish Women Artists: 250 Years of Challenging Perception which I saw on Tuesday in Edinburgh – more details of that to follow soon. But today, as I said, we will look at Crivelli.

La Madonna della Rondine, or ‘The Madonna of the Swallow’, as it’s commonly known, has the distinction of being one of only two 15th Century Italian paintings in the National Gallery’s collection to still have its original frame. Renaissance architecture, based on Roman forms, frames the main panel, with carved, painted and gilded pilasters supporting an architrave. The two bases of the pilasters are painted, forming either end of the predella, the strip of paintings along the bottom which decorates the box-like structure which would originally have helped to support the painting on the altar for which it was commissioned. This was in the church of San Francesco dei Zoccolanti, Matelica, in the Marche, although as the building has since been restructured, the chapel is no longer there.

The swallow of the title is perched atop the back of Mary’s marble throne, its head all but silhouetted against the flat gold background. Unaware of migration, all people knew was that swallows went away in the autumn and came back in the spring. Inevitably their return became a symbol of new life, and so of Christ’s resurrection. The various fruits and flowers are also symbolic in a wide variety of ways, but, to counter my usual prolixity, I’m just going to say that I don’t have time to go into all of that right now. In this detail we see the heads of four people – the Madonna and Child, obviously (I’m assuming you know who they are), an old man with a long white beard wearing a broad-brimmed red hat, and a young man with long blonde hair (the style of the hair, and the fact that it is not dressed or covered, tell us that this is a man). All four have haloes, so we know that they are all holy. Jesus’s halo has a red cross on it, which is one of the ways we know that this is Jesus, rather than any other holy baby ,(which, in its turn is one of the ways we know that this is Mary, rather than any other holy woman…). Two of the haloes are shown as circles, flat against the picture plane, whereas the others float freely in space, foreshortened to make them look like solid, three-dimensional objects. I don’t think there is any particular meaning to this, it’s probably more of a practical consideration: I think Crivelli is simply making sure that the haloes don’t bump into the red hat and Mary’s crown. However, he often plays with real and imagined space in very sophisticated ways. Placing the bowls of fruit and flowers, which are clearly seen as if from below, against the flat gold background is just one example, the difference between the haloes is another.

The man on the left is St Jerome (c.343-47 – 420), an advisor to the Pope and so retrospectively made into a Cardinal of the church (a role which didn’t exist when he was alive). This explains the ecclesiastical robes, with broad-brimmed red hat, and red cloak. One of his major achievements was to gather all the biblical texts, learn the languages they had been written in originally, and then translate them into a coherent form of Latin, the translation we now know as the Vulgate. He was considered one of the four Fathers of the Church, along with Augustine, Ambrose and Gregory, which is why he is holding a model church. His translation of the bible, together with his other theological writings, help to illuminate God’s word – hence the tiny beams of golden light you might just be able to see shining out of the door of the church. You can read the two books in his right hand as the old and new testaments, if you like, or as the ‘original versions’ (in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek and Latin) bound into one volume, and the translation (all Latin – the Vulgate).

On the other side is St Sebastian, a third century saint martyred as a Roman soldier who not only converted to Christianity, but who also encouraged fellow Christians to go to their deaths, and therefore, their salvation. You are probably more familiar with him looking like a human pin cushion, stripped to the waist and shot with arrows, but in the Marche he is more often shown fully dressed as a young aristocrat. He does, however, hold a single arrow, which is enough to tell us who he is.

At the bottom of the painting we see more symbolic fruit tied together with string to make a garland. The string itself is tied to a nail just below the golden hem of Mary’s cloak – to the left of the saggy knee of St Sebastian’s tights (or hose, if you want the proper name). The fact that the nail has been hammered in to the step of the throne suggests that it this step is not marble, but wood painted to look like marble. In the same way, the altarpiece is painted on a wooden panel – so this element of the composition is a wooden panel painted to look like a wooden panel made into a step: one more of the sophisticated games that Crivelli is playing about the nature of art and reality. Another is represented by the coat of arms at the bottom centre, which appears to be attached to the front of the step on which Jerome and Sebastian are standing. The front of the step is carved and gilded with decorative foliage, and below it the frame is gilded. Jerome’s red robe falls over the edge of the step, and Sebastian’s bow projects across it – into our space, apparently – and both cast shadows onto it. The coat of arms also casts shadows, and is clearly attached, if this detail is to be believed, in front of the painting and frame. Of course it’s not – this is all trompe l-oeil – tricking the eye. The coat of arms is that of the Ottoni, one of the leading families of Matelica, for whose chapel this painting was commissioned. There were two patrons though, one a man of the church, and another with military connections – hence their choice of Jerome and Sebastian, a Cardinal and a soldier, on either side of the throne. Jerome is at the right hand of Jesus, known as the ‘position of honour’. The church – within religious paintings at least – had the higher status in the church and state dichotomy. Like the fruit, the lion is also symbolic: it is far too small to be a real, fully grown lion. It has a long – and surprisingly neatly combed – mane, and so is clearly not a cub. Its presence confirms that this is St Jerome. In a story which is actually taken from the classical figure Androcles – there are always more stories, and yet they keep being re-used – Jerome removed a thorn from the lion’s foot, which is why it is holding up its front right paw. You might just be able to see the thorn. The lion was so grateful that it remained with the saint for the rest of the latter’s life. Below St Sebastian’s feet and bow, there is a piece of paper.

This is a cartellino, a small piece of paper (we saw one at Flora’s feet last week), bearing Crivelli’s signature. It is apparently attached to the surface of the painting itself, rather than being attached to the fictive, carved, and so three-dimensional step – another example of trompe l’oeil. I’m delighted to see that Crivelli didn’t ‘attach’ it on a level – the detail shows that it’s at a slight angle, which I hadn’t realised before, and suggests he wasn’t being overly careful when attaching it – he’s only human after all! The tilt makes it seem just a little bit more real, stuck on after everything else was finished, even if in reality he would have known it was going to be included from the outset. Enough of these cartellini are painted elsewhere (Bellini was especially fond of them) to suggest that many artists did indeed put their names onto pieces of paper and then attach them to their work with pins, or small blobs of red wax. They would have become detached very easily, which could account for the many unsigned paintings which survive – and for our ignorance about the identity of the artists who painted them. The inscriptions states

CAROLUS.CRIVELLVS.VENETVS.MILES.PINXIT.

As ‘MILES’ means ‘Knight’, this can be translated as ‘Painted by Sir Carlo Crivelli from Venice’, giving us a rough date for the painting. Crivelli was knighted (although we’re not entirely sure by whom, or why) in 1490, and died sometime around 1495 (in that year his wife was described as a widow). Below the main panel is the predella.

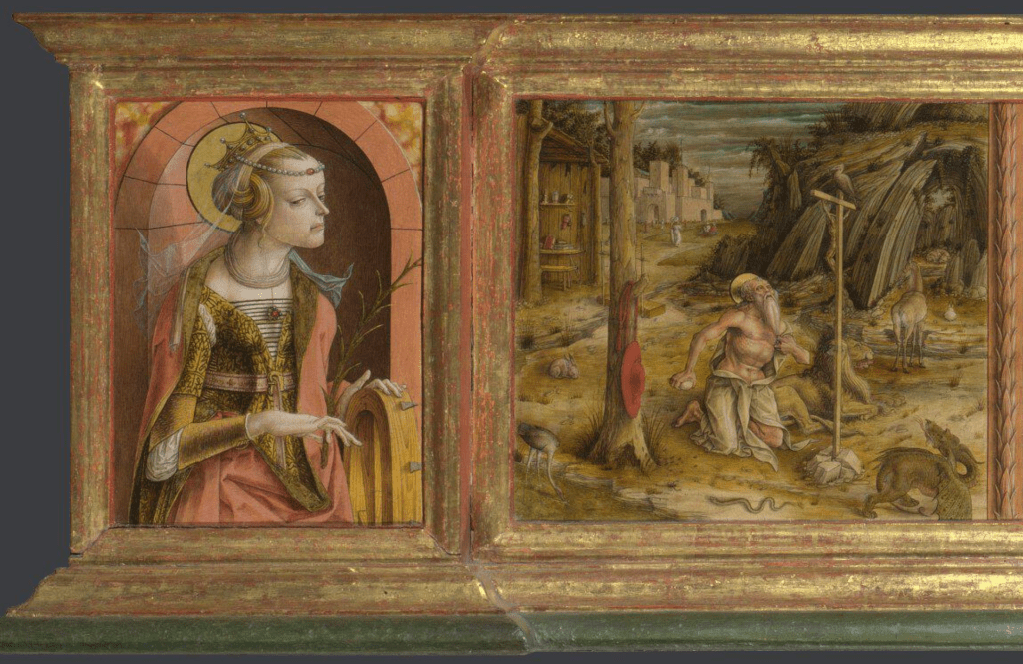

In the niche on the far left is St Catherine, holding the spiked wheel which formed one of the instruments of her torture. They tried to kill her by tying her up and scraping her to death with the sharp spikes, but God intervened and broke the wheel – one of the many stories (and there are always more) which are told in The Golden Legend, which I have mentioned often. Some paintings of this show fire coming down from heaven, and sparks flying from the wheel – hence the name of the Catherine Wheel, a type of spinning firework. She also holds Crivelli’s version of the palm of martyrdom, although his botanical accuracy leaves a lot to be desired. To the right of her is an image of St Jerome repenting in the wilderness, his red cardinal’s hat tied to a tree, and a full-sized lion lying down behind him. His study, a shack in the desert, can be seen in the background on the left. The dragon slinking away in the foreground on the right is interpreted as representing the sins of which he is repenting make a final, reluctant departure.

In the centre of the predella is the Nativity – the birth of Christ – set in a stable which is precariously constructed among ruins, and painted with strong foreshortening which pulls our eye towards the walls of Bethlehem in the background to the left. Through the archway on the right we can see the shepherds looking up – as are some of the sheep – towards the angels, who are holding a giant scroll and announcing the holy birth.

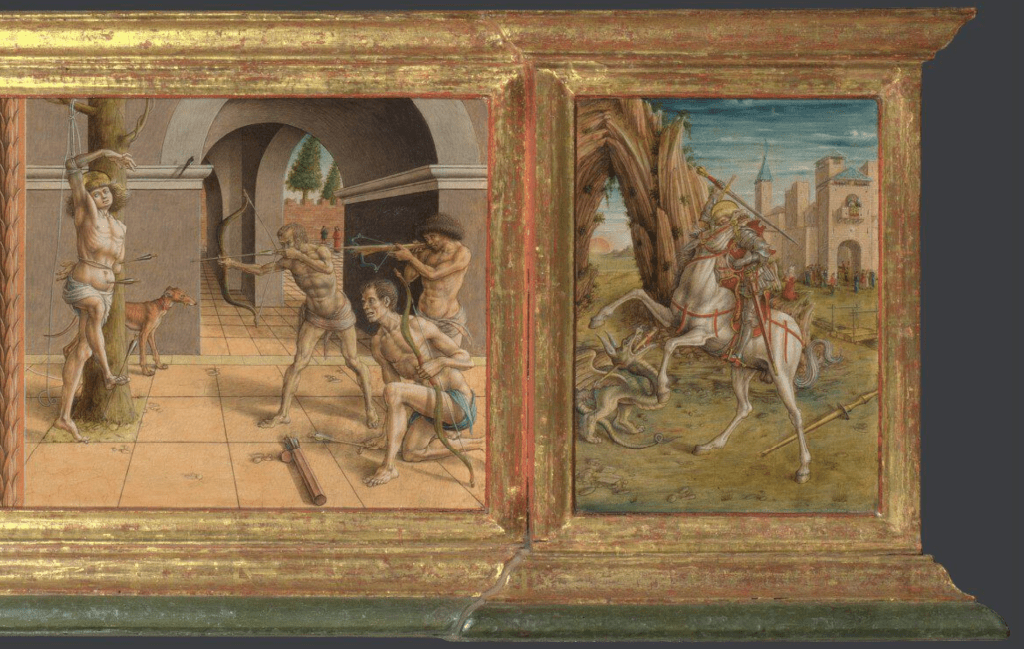

To the right of this we see the martyrdom of St Sebastian. He is more traditionally dressed in a loin cloth, strung up on a tree, with his executioners – who had previously been soldiers in his own troupe – shooting him with arrows (one of them, anachronistically, is wielding a cross bow). The tree grows out of a gap in the paved floor which has a bold, more-or-less central perspective. This leads our eye through an arcade to a city wall, presumably intended to represent Rome, in the far distance. On the far right is St George on a white horse with red trappings, subtly evoking the saint’s flag. It looks as if Jerome’s dragon has slinked its way through the Nativity and past St Sebastian – most of the way along the predella – only to meet its final come-uppance here. The choice of St George, paired with St Catherine at the other end of the predella, echoes the choice of Sebastian and Jerome in the main panel, and again relates to the vocations of the two patrons. The three narrative stories between the paired saints tell us more about the people above – Jerome’s penitence below the full-length St Jerome, the Nativity beneath the Virgin and Child, and the Martyrdom of St Sebastian below the clothed representation above. This was just one way of structuring a predella. An alternative was to tell several episodes from the life of most important saint in the altarpiece, usually the dedicatee of the chapel or altar itself, but there were other possibilities.

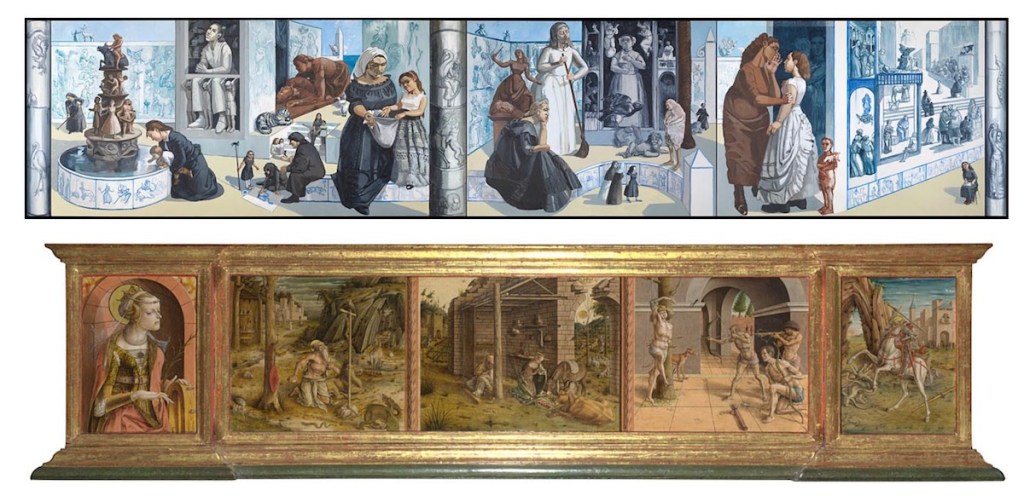

It was the predella which really caught Paula Rego’s attention. She imagined the possibility of entering the painting, looking round the corners of the buildings, and behind the columns which separate the images, and going as a far as the walls which close off the backgrounds in most of the images. Maybe they were all connected, she thought, and maybe there were other stories of other saints to be found there, hidden away. It was this, the strong perspectives and bold constructions, not to mention the all-but barren landscapes, which inspired her in the painting of Crivelli’s Garden. She combined this with a critique of the male-orientated vision of the vast majority of the paintings in the National Gallery’s collection – but more about that on Monday. Rego’s finished work has similar proportions to Crivelli’s predella, as it happens, albeit on a far larger scale – but I think that’s merely a coincidence.

There must be something about La Madonna della Rondine: Paula Rego was not the only Associate Artist at The National Gallery to be inspired by it. As the first Associate, she was resident in 1989-1990. The fourth, from 1997-99, was Ana Maria Pacheco, who painted Queen of Sheba and King Solomon in the Garden of Earthly Delights – but that’s another story. There are always other stories, and Crivelli’s Garden is full of them.

Dear Richard

You mean 28th August!

Best wishes

Andrew Crosthwaite

[Apple_logo.png]

Core Values

07831 434 043

andrew@corevalues.co.uk

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re so right, I did! I’ve done this one before recently – proof reading for spelling and typos, but not for the correct month. Fortunately the ‘this Monday’ gives it away… as does the correct date on the event itself… but thank you for alerting me to the error. Must stop wishing my life away!

LikeLike

Dear Dr Stemp,

Thank you very much for your fascinating analysis of this Crivelli painting. The details in your descriptions and explanations are really interesting. I miss so much when I look at a painting by myself and it’s wonderful to read your detailed observations and interpretations.

Thank you again.

Kind regards,

Eithne White. (Co. Wicklow, Ireland).

https://www.avast.com/sig-email?utm_medium=email&utm_source=link&utm_campaign=sig-email&utm_content=webmail Virus-free.www.avast.com https://www.avast.com/sig-email?utm_medium=email&utm_source=link&utm_campaign=sig-email&utm_content=webmail <#DAB4FAD8-2DD7-40BB-A1B8-4E2AA1F9FDF2>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Richard

Thank you so much for this.

In college we had to write a compare and contrast essay on two Renaissance altarpiece.

I chose this, Crivelli’s ‘Madonna of the Rondine’ ans Giovanni Bellini’s, ‘San Giobbe Altarpiece’.

Really fascinating to read your work on Crivelli.

Much appreciated.

Fiona Marshall

LikeLike

What a great comparison – I do love the San Giobbe, although I wish that, like the ‘Rondine’, it were still in its original frame (which, as I’m sure you know, is still in the church of San Giobbe). The San Zaccaria altarpiece just pips it to the post as my favourite, though!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Richard,

Funnily enough it was a toss up between The San Giobbe and The San Zaccaria. It was St. Sebastian that swung it as he is in both paintings and is depicted in such contrasting ways!

Yes, it’s a pity the Giobbe is not in it’s original frame. I think that was down to some guy named Napolean 🙈

What a treat to have the Rondine in it’s original frame. If anyone is interested in further reading on Crivelli’s Rondine there is a great piece ‘An Altarpiece and its Frame: Carlo Crivelli’s “Madonna della Rondine’ by Alistair Smith, Anthony Reeve, Christine Powell and Aviva Burnstock.

Also, another great book ‘Mantegna and Bellini’, by Caroline Campbell, Dagmar Korbacher, Neville Rowley and Sarah Vowles. A mighty tome but well worth a read.

Richard, I really enjoyed your description of the predella. The link between Jerome, Sebastian and the Virgin and child is hugely interesting.

I love the exquisite detail in the predella.

I also note that the Ottoni coat of arms that Sebastian ‘s left foot is pointed towards is placed directly in the middle of the Nativity scene bellow. For me, this is both poignant and quite relevant.

Over and out.

Fiona Marshall

Wicklow

Ireland

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks – for some reason I’ve never come across that paper: should have read it before writing the blog! And for anyone who’s interested it is available to download online (for free):https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/technical-bulletin/an-altarpiece-and-its-frame-carlo-crivellis-madonna-della-rondine

LikeLike

Hi Richard, I wanted to tell you that I would have come to Glasgow with you if I hadn’t had two great days there last September with Sheila L. but if any of your fans read this I would like to encourage them to sign up for the trip. There are wonderful things to see and having always been an Edinburgh person, having been born there, I now think Glasgow might be ‘miles better’!

I saw the Crivelli/Rego exhibition recently and enjoyed it a lot.

Love Fiona

LikeLike

Sorry you won’t be there – but thanks for the recommendation! I’m really looking forward to it – some great art among some rather idiosyncratic hangs, not to mention, brilliant buildings.

LikeLike