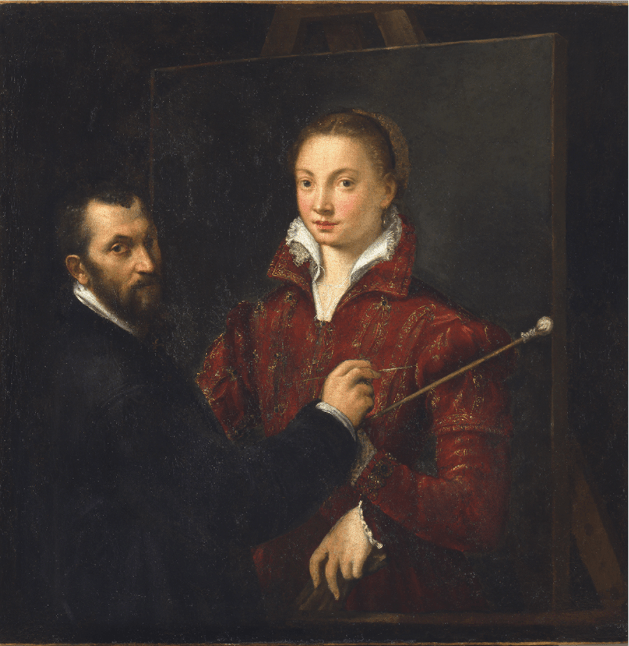

Sofonisba Anguissola, Bernardino Campi painting Sofonisba Anguissola, late 1550s, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.

Who could not love this artist given her name? Quite apart from her talent, of course. I will come back to her very soon to explore her life and her work in more depth. But for now, I want to look at a painting which shows that, contrary to the assertions of many men over history (mainly artists who were protecting their pitch) women really did have the intellectual and conceptual ability to understand art and what art can do.

It is a double portrait, as the ‘title’ suggests – but of course, this is only what some people choose to call it now. You can also find it listed as ‘Self Portrait with Bernardino Campi’ – but that really misses the point. What is remarkable is that, as far as I am aware, no one has ever thought this painting was by him – after all, he is the one painting. The self portrait by Judith Leyster (Picture Of The Day 34) was for years attributed to Frans Hals, because it is in a similar style to his, even though she herself is sitting there in front of an easel, holding a palette and around 18 paint brushes. Like the Leyster, we have a painting within a painting – in this case, a man painting a portrait of a woman – what could be unusual about that? It would make sense to assume that he was the artist. He looks towards his subject, painting the delicate details of her elegant dress. The padded end of his mahl stick (POTD 28) is propped on the very edge of the canvas so that he can rest his right wrist on it, thus keeping his hand steady to paint the details of the embroidery. His profile cuts across the left edge of his canvas and the easel can be seen projecting above it. The lower edge of his canvas can be seen, towards the bottom of the painting itself, and to the right we can also see the canvas stretched around the stretcher. As for the portrait he is painting, it is beautifully executed, and surely, almost complete. The subject wears a rich red, high-collared and sleeved bodice, embroidered with gold thread. Underneath this she has a white chemise, with its lace-trimmed collar standing up inside the collar of the bodice, delicately laced at the neckline. There is just a hint of a large drop-pearl earring, and her left hand droops at the wrist, holding a pair of deep red gloves, a sign of both class and sophistication. This is clearly a wealthy and successful woman. A beautiful executed portrait, in a perfectly standard painting, but it all seems perfectly normal. Until you remember that Sofonisba painted it.

Think about it this way: what are they looking at? He looks round towards us, but why? To catch our eye perhaps? To see if we approve of his efforts? Or is he looking at a mirror to catch his own reflection to paint his face? He would have had to do that to capture his own appearance, after all – but at the moment, he is painting Sofonisba’s dress – so he must be looking at her. And of course he’s looking at her, because it is she who is actually painting this, and, while his face was being painted, she must have been looking at him. And what about her? Who or what is she looking at? Well, if he’s painting the portrait, she must be looking at him, but, as she painted both subjects, she must be looking at herself, in a mirror: she had to, or she wouldn’t know what to paint.

If that hasn’t done you head in, here are a few more questions. Who is in charge here, and why? Whose face is clearer? Which character is more dominant? To my eyes – and it’s always worthwhile remembering that everyone sees things differently – Sofonisba stands out far more clearly than Bernardino. Her face is brighter, clearer, sharper. Her costume is richer – and brighter – whereas his black doublet fades into the background, and so does his hair and beard. He tones in. His face appears softer, the lights and shades more finely, and more subtly, blended. It is more painterly, I would suggest – and this makes her look more alert, more alive. He looks at us – and ultimately, whatever they were looking at during the course of the development of this work, the intention was to make it look as if they are looking at us, to make them seem more immediate and present – he looks at us with interest and understanding, but out of the shadows. By contrast, she is almost sphinx-like in her immoveable security. And she is higher up – which has always implied a higher status. When painting her face (if he were actually painting her), he would have to look up to her. And so he should – she is his creation. Not just in this imaginary portrait by him, which is actually by her, but in the person of Sofonisba herself. Because Bernardino Campi taught her to paint from the age of 14. She is everything he made her, and in this painting, probably painted when she was in her late 20s, she acknowledges that. But she also puts him in the shadow. And if that’s not sophisticated enough, there is another suggestion: that she has painted each of the subjects in their respective styles. So she paints him how he would paint himself, whereas she paints herself, as she did quite often, using her own technique.

Conceptually I think this work is unparalleled before the 16th Century, and also, I suspect, for some time after. The self portrait by Catharina van Hemessen (POTD 28) is the first we have of an artist depicting themselves painting, and that was in 1548. I think it was Sofonisba who painted the second, in 1556. Today’s Picture would have followed a couple of years later. An artist painting someone else painting them. I might be missing the obvious, but I’m not sure I even know of any other examples – please tell me if you do!

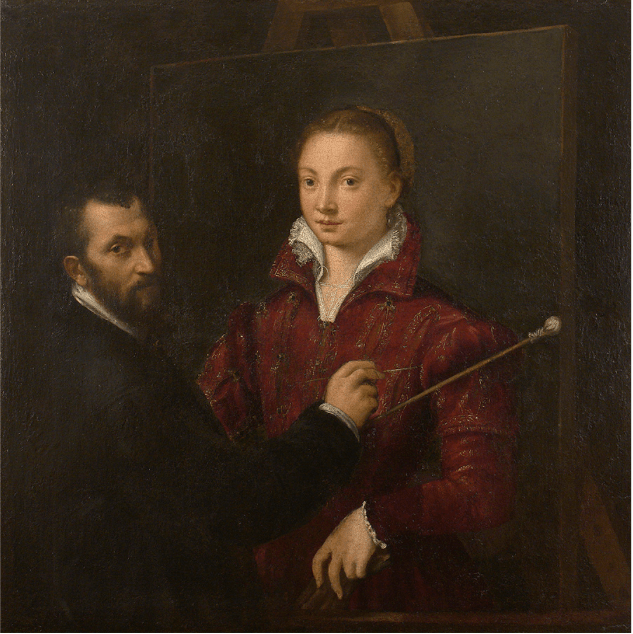

I would be more than happy to leave it here, but I should mention the painting’s curious history, partly because, if you were to look it up online or even – yes, it is possible – in a book, it might well look rather different. Look at the following three versions, and before you read any further, try and spot the differences.

I don’t know if you’ve ever visited the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena – it is the main art gallery, although people rarely go. There is so much else to see in the city, including genres of painting you can’t find anywhere else. There are frescoes extolling the virtues of Good Government, frescoes explaining the foundation of a hospital and all of its duties, and frescoes exploring the life of a fairly inconsequential Pope, and they are still on the walls for which they were painted, so why bother going to a museum? Siena is a city which really deserves more than the day trip it usually gets. But, until recently, the Pinacoteca has not been a great place to go – dingy, dirty even, with absolutely everything they could squeeze in hung on the walls in an endless sequence of shabby rooms. To be honest, I don’t know what it’s like now, because last March when I was there they were in the middle of refurbishing – probably the first time in seventy years or so it’s seen as much as a lick of paint. So by now it could be glorious. But I used to actively avoid taking my students there as it was one of those buildings that saps the spirit (I have a list). Had I spent more time there, I would have learnt how to cherry pick the best – but when I first went, this painting would never have made the cut. It was extremely dull. A black painting with two faces, two hands and a mahl stick. You could just about see the edge of the canvas and the easel, but it really was nothing remarkable. Until they cleaned and restored it in 1996, when they found out that Sofonisba was not originally wearing such a dark dress – but a wonderful red and gold one. But they also found out that she had two left hands. For five years, that is how they exhibited the painting – with one hand reaching up behind Bernardino’s, and the other lowered, holding her gloves. It was only six years after the first (recent) restoration that the conservators returned to the portrait and painted over the second hand – and so, since 2002, it has been exhibited as we have discussed it, the assumption being that Sofonisba must have intended it to be seen like that.

When you look at the details it only begs more questions. What would she have been doing? And why did she change her mind? And who changed her clothes? All of the answers to these questions must by hypothetical, but to me it looks as if she was reaching up to take the paintbrush. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses Pygmalion was a sculptor who fell in love with one of his own creations, and, having invoked Venus, goddess of love, the sculpture was brought to life – the power of art is that it can take on a life of its own. Here however, it is not love but talent that brings Sofonisba to life, taking over from her Master, like a relay runner taking the baton. A common topos – a regularly used phrase used almost conventionally – for a portrait was that ‘it only lacks a voice’. Well here, she may lack a voice, but she has come to life. Of course it’s possible that something else was going on, nothing to do with painting. Was she taking his hand? And if she was, would that have been appropriate? And what if she had meant to show herself taking his brush, but it looked as if she were going to take his hand? Maybe that’s why she changed it – or maybe she changed the position of the hand simply because it didn’t work, it looked too strange. Or maybe, she changed it because she looks more sophisticated holding the gloves. Whatever it was, it seems likely that she painted over the original hand, but over the years the change had become visible. Some paints fade, some change colour and some go transparent, revealing what are called pentimenti – changes of mind, as the artist ‘repents’ and repaints. So the second hand might have started to reappear. In the 19th century people didn’t like the ‘bright’ colours of earlier paintings, so to cover up the pentimento and make the whole thing look more balanced, more like an ‘old master’ painting, it could have been repainted, with a far darker dress for this respectable lady. Under most circumstances there would be no qualms about removing a 19th Century layer of paint from a 16th Century painting, but, having removed an earlier ‘overpaint’ which clearly wasn’t original, what are the ethics of covering up something that was? Was the first hand (or is that the second hand?) original though? Had it ever seen the light of day? Well, these are the choices that conservators and curators have to make. But rest assured, that hand hasn’t gone – it has just been disguised, covered up – and the conservators could get it back by taking off the new overpaint in a couple of days. Possibly quicker, but you never rush a painting, in case you damage it. I for one am happy to see it as it is now. And when I next have a chance to go to Siena, I will – and I hope to find it in a resplendent, newly decorated and refurbished art gallery!

3 thoughts on “Day 77 – Sofonisba Anguissola”