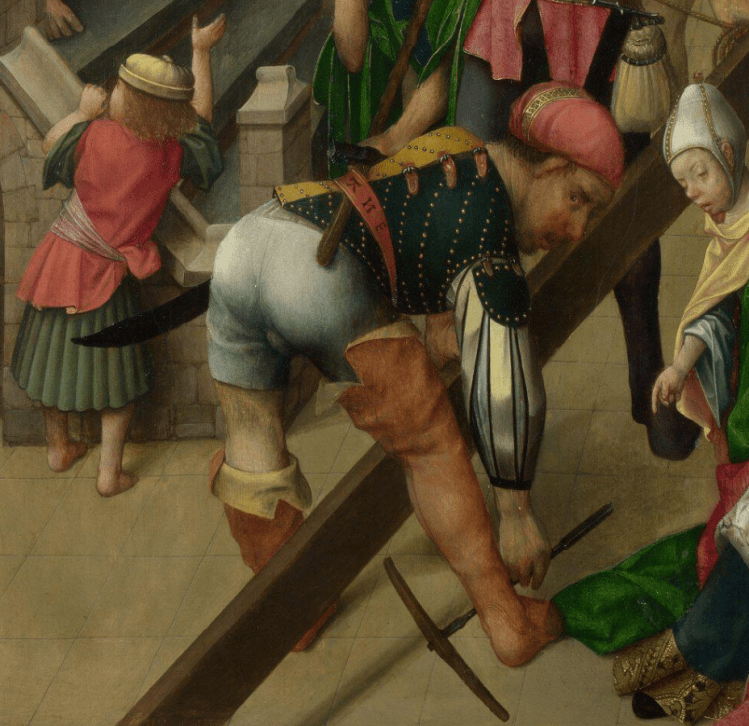

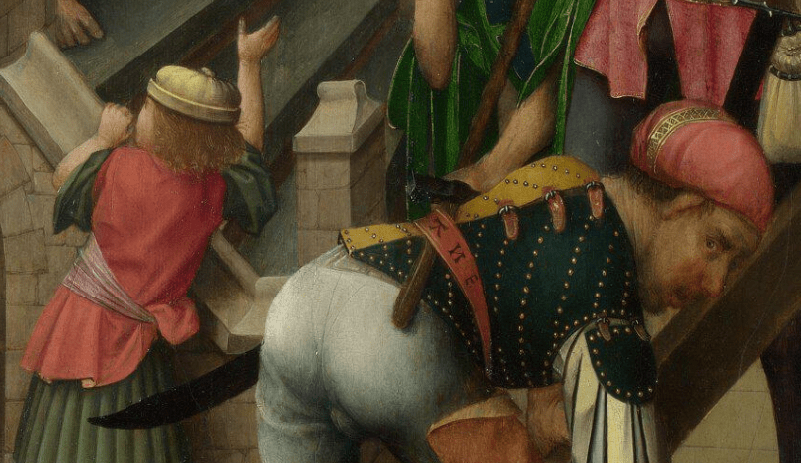

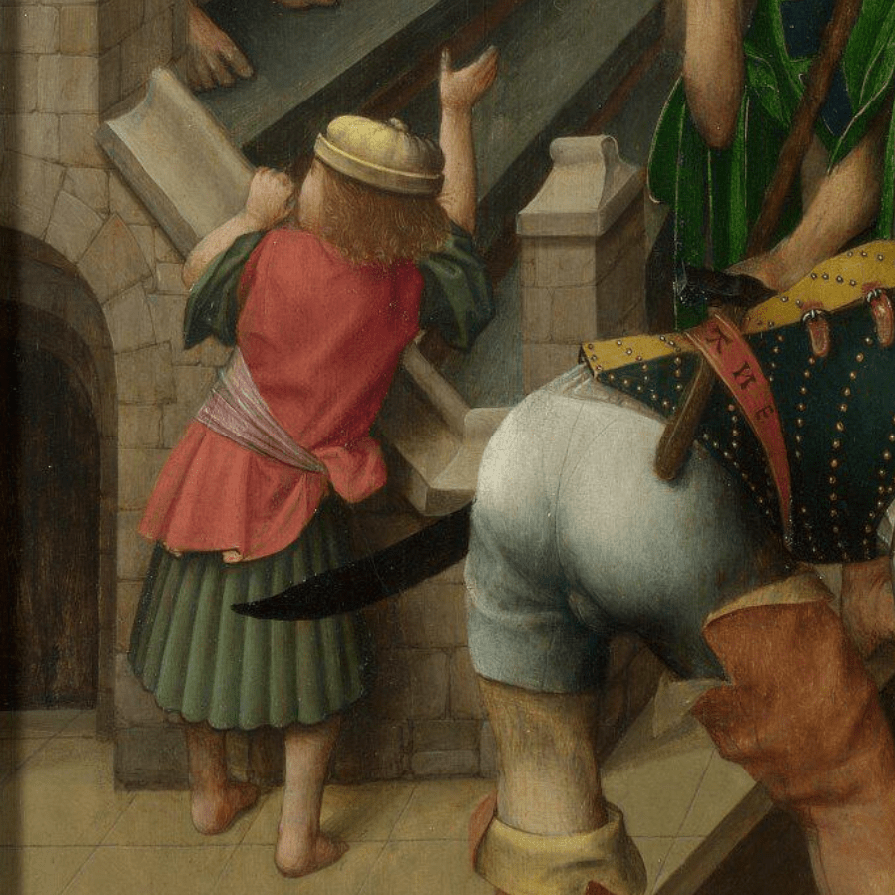

In the words of comedian, actor and writer Arabella Weir, ‘Does my bum look big in this?’ Not only does this man bend over to give us a chance to contemplate an answer, but he also turns round to look us in the eye – indeed, he is, I suspect, one of the very few people in the painting who do look at us, aware of our presence, thus inviting our participation in the events depicted. His gaze connects us to the painting, while the plank, or beam, which he is holding with his left hand leads our eye in further, as we saw in Lent 9. We now know, of course, that this plank, or beam, is part of the cross. His right hand reaches down, arm fully stretched, to pick up his auger (not his pick), which he will use to make guide holes at the bottom and on both arms of the cross, so that later it will be easier to drive in nails. There are other paintings where you can see this in action. The boy with the improbable hat (Lent 7) is pointing to the auger, acknowledging its relevance, and also helping to structure the painting: his gesture parallels the length of the beam, and helps to keep our eye looking into the painting, and to the right, the direction that Jesus will soon travel on his way to Calvary.

There is something comical about bottoms, particularly when they are displayed so brazenly. They imply a sense of vulnerability, I think, especially when your hose is down. We could see, even in the small detail in Lent 9, that the left leg had collapsed. Someone suggested that the hose looks almost more like thigh-length boots – and it does. But this shouldn’t be a surprise: our mistake is to confuse ‘hose’ with ‘tights’ – thin, almost evanescent – but hose was intended to fully clad the legs – not only to cover them, but to keep them warm. Before lycra, and even before elastic, they could be tied up with garters, but were often attached to the bottom of the doublet with laces – rather like shoe laces, with pointed metal caps (‘aglets’) to stop them fraying. Perhaps for that reason they were called ‘points’. When Malvolio decides to dress precisely how he believes, in error, that Olivia wants him to, in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, he says he will be ‘point-devise the very man’ – he means that he will be ideally dressed and perfectly presented. Not this man here: no points, so his hose has fallen down. It reminds me of the Whitehall farces – and no, I am not referring to contemporary politics, and no, I am not old enough to have seen any of them. But I know that, in these ‘classic’ comedies at the Whitehall theatre in the 50s and 60s, usually starring Brian Rix, there was usually a point where the hapless hero’s trousers would fall down, and it would always get a laugh. We are meant to laugh at this man – he is our comic chorus, like the Porter in the ‘Scottish Play’ or the Gravedigger in Hamlet. He is there to warm us up, to grab our attention, to get our emotions moving, to lower our guard – because later we should weep.

And it’s not just the bottom. He shares something in common with the right-hand sculpture adorning the palace which we saw in Lent 5, about which I said, ‘his buttocks are turned towards us… and… there is more than a hint of testicle’. Fine. Dress how you like. But don’t stand astride a plank. Or beam. If the man at the other end lifts it up much higher, there will be a nasty accident. This is part of the comedy, and it is also one of the ways in which the cruelty of these men is undermined – they are ugly, low and laughable. However, hardly anyone is paying attention to him – apart from us, perhaps. A child at the bottom of the Scala Santa looks up towards Jesus and waves. He really shouldn’t be here, as he has wandered out of another image, but seems to be morbidly interested in Christ’s suffering: as the Dutch used to say in the 17th Century (and maybe they still do), ‘Soo voer gesongen, soo na gepepen’ – ‘As the old sing, so the young pipe’. He’s been given a bad example.

Our artist is quoting from a print of The Flagellation by Dutch painter and printmaker Lucas van Leyden, probably as the design for a small stained glass panel, a vignette that would sit in the middle of a plain glass window. It was part of a series now known as The Circular Passion, and is dated 1509. This tells us something important: our painting must date from 1509 at the very earliest… but probably later.

I hadn’t thought of it as comedy but the way you explain it is pure slap- stick. But I am still a bit puzzled by ugly people in Northern Renaissance painting. It seems such a characteristic compared with Italian Renaissance where often the only ugly person is the patron or donor. Is it a shift in painting from life rather than Platonic ideals? Or were Italians just much more handsome?

LikeLike

They just had a different outlook on life. They chose to represent different things to express different ideas. The northern Europeans portrayed life in all its variety, the Italians went for the ideal. In a way it is a bit like the difference between Aristotle and Plato, learning from what we can see, or imagining what would be the ‘original’ form. The mistake is that artists were actually painting what they saw… it’s a natural mistake to make, but ‘art’ is ‘artificial’, it is a choice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your comments are hilarious. I’ve always learned that the one who is looking out directly at the audience is most likely a self portrait of the artist him/herself. I can’t imagine that this artist would be so immodest as to present himself in such an uncompromising position, and be party to such a deed.

Do you give courses on Shakespeare’s works? If not, I wish you would!

LikeLiked by 1 person

To be honest, it’s a common assumption that an artist might be looking out at us, and occasionally they do. But more often it is someone else whose job is to make us part of the story, as described by Alberti in his book ‘On Painting’, written in the 1430s. Given that sometimes the only things looking at us are animals confirms the fact! Caravaggio, when he paints himself, is involved in the action, as are others, and doesn’t look out, while frequently identified ‘self portraits’ are supposed to be of artists for whom we have no known image – so we have no way of knowing what they actually looked like. However, with time the ‘assumption’ has grown into ‘fact’…

I don’t teach Shakespeare – I wish I knew enough to do so. I just about get away with pretending I know about art, but couldn’t get away with Shakespeare…. The best thing is to watch – and listen (as in ‘audience’ rather than ‘spectator’) in the same way that with art you should just look. Oh for the day when theatres and museums will be open again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Does the lettering on the workman’s belt signify anything

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good question – but no. It is meant to look like ‘foreign’ writing, but it isn’t.

LikeLike

I am so enjoying your series. I am not an artist but have become seriously interested in art history in the last few years, and you are doing what I have always wanted: analysing/explaining what you can see in front of you, because as a non-artist, I think “Wow, that’s incredible”; but wasn’t understanding what I was looking at. I “discovered” you through the National Gallery’s ‘Stories of Art’, which I stumbled upon accidentally. I loved your section, (well, I love all of it). Please never stop!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I do hope you continue to enjoy it all!

LikeLike

Looking at the children in the context of Christ’s suffering made me think of Matthew 19.14 King James version.

Suffer little children,and forbid them not, to come unto me: for such is the kingdom of heaven.

It is a tenuous link and not the same meaning but as a child I believed it to mean suffer and not allow. Are these children being allowed to witness this for some reason?

Sorry if I haven’t explained my thoughts well

LikeLike

To be honest I think this is simply an example of ‘life as it is lived’ – suffering as public spectacle, as public executions would have been – and children would have been there.

LikeLike

Yes I do see that. Thank you for grounding me in the experience at the time. I tend to overthink things and go off at a tangent

LikeLike