Angelica Kauffman, Invention, 1778-80. Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Rather brilliantly, Tate Britain’s encyclopedic survey of Women Artists in Britain, 1520-1920, opens with Angelica Kauffman’s Invention. It was one of the four Elements of Art which she was commissioned to paint for Somerset House, where they were installed in the ceiling of the Royal Academy’s new Council Chamber in time for its opening in 1780. Invention was one of the many reasons that it was said that women couldn’t become artists, as it was one of the many qualities that men said women lacked. Indeed, it was probably the chief quality, as the merely practical ability to copy things which already existed – whether portraits or living human beings – was granted them. And that is why I think it is a brilliant opening to the exhibition. It also means that the first of my talks, Up to the Academy, will be framed by Kauffman’s work, as she was, famously, one of the two women who were founder members of the Academy in question. The other, Mary Moser, is far better represented than I was expecting, just one of the many reasons to go. This first talk will be on Monday, 1 July at 6pm, and it will be followed by Victorian Splendour and From photography to something more modern on 22 July and 5 August respectively, scattered as the result of an unexpected theatrical engagement, and a long-planned holiday. If you want to book for all three, I have, against my better judgement, re-instated the tixoom bundle which will give you a reduction on the overall cost of the tickets (available via those links). I will cross my fingers until 5 August, hoping that nothing else gets in the way!

As I said above, Angelica Kauffman’s painting Invention is one of a series of four, and if you would like more background for the commission, I wrote about two of the others way back in May 2020 (see Day 48 – Colour and Design). The series was dedicated to the Elements of Painting, as defined by the first President of the Royal Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds. The other three are Colour, Design, and Composition. While ‘colour’ and ‘composition’ are standard terms, the difference between ‘composition’ and ‘design’ might not be obvious. Sir Joshua was aware of historic debates among European artists and theoreticians, and chose a direct translation from the Italian ‘disegno’ to give us ‘design’, even if ‘drawing’ would be a more logical choice given its standard use in English. But we’re not thinking about any of these today. Instead, we will focus on Invention, that quality which, as I have said, women were said not to possess. How do you come up with the ideas that make a great work of art? And for that matter, how do you represent that concept? This is how Kauffman chose to personify it.

Invention wears a white dress and a butterscotch-coloured cloak, the former matching the lighter colours of her pale complexion, while the latter blends with her golden hair. She sits in a landscape on a rock, which has undefined vegetation growing around it. Her right knee is raised with the shin vertical, and the ball of the foot planted firmly on the ground, while her left knee is lower, the foot trailing off to our right. A dark blue globe lies on the upper surface of the sloping rock and rests against Invention’s knee. Her right hand, draped with the butterscotch cloak, rests on the globe. Her left arm is raised, the hand upturned, as if towards the heavens. She gazes upwards, past what, at first glance, might appear to be a peculiar form of headdress. On the far right there are distant, blue mountains, with a river, or lake curling around their base – not unlike the mountains of Switzerland, where Kauffman was born. On the other side of the painting, in there middle ground, there are two tree trunks. They cross each other (they grow on opposing, steep diagonals) and close off the composition to the left.

Invention’s right hand is resting on what can be seen to be a celestial globe, with five stars marked quite clearly in white. There are two between her thumb and forefinger and three in a row lower down and to the left. Her index finger points to the globe, and could be pointing to the lowest of these three stars. Below it, and a little to the right, there is a sixth star in the shadows. It’s not a constellation that I recognise, but I have never considered myself to be an astronomer (and yes, before you suggest it, there are hints of Orion). The headdress – if that is indeed what it is – is in the form of two wings, both white, and with well-defined plumage, although it is not clear whether this is part of Invention’s anatomy, or something she is wearing. The clouds are slightly darker behind the head, allowing the face to stand out clearly. Some of the billowing forms between the wings may relate to a pentimento – a change of ideas about the length and form of the hair.

Whatever the meaning of the various elements portrayed, the painting is, surely, incredibly inventive in itself. But what could it all mean? It really helps if we turn to a book published originally in 1593, the Iconologia by Cesare Ripa, in which various ‘abstract’ qualities, whether virtues or vices, arts or sciences, moods and even cities were described as visual, allegorical figures. The work became truly successful – and useful for artists – ten years after its original publication when a new edition was brought out which included woodcuts, thus giving visual form to some of the many concepts described. Many other editions followed, including an English translation, published in 1719. I have chosen this version as a result of its availability: it was digitised in 2009 by the Warburg Institute, and is available online. Below is the title page – I hope you can read it, but don’t worry if it’s not clear – followed by the description of Invention, which I have transcribed for the sake of clarity.

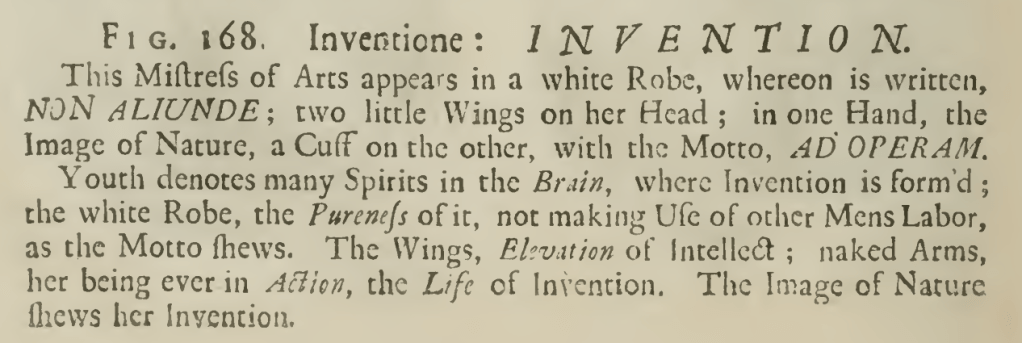

FIG. 168 Inventione: INVENTION.

This Mistress of Arts appears in a white Robe, whereon is written,

NON ALIUNDE; two little Wings on her Head; in one Hand, the

image of Nature, a Cuff on the other, with the Motto, AD OPERAM.

Youth denotes many Spirits in the Brain, where Invention is form’d; the white Robe, the Pureness of it, not making Use of other Mens Labor, as the Motto shews. The Wings, Elevation of Intellect; naked Arms, her being ever in Action, the Life of Invention. The Image of Nature shews her Invention.

To clarify, NON ALIUNDE translates as ‘not from elsewhere’, while AD OPERAM means ‘to work’, as in ‘for the purpose of…’ But how does the illustration from the English edition compare to Kauffman’s painting?

The white dress is more overtly depicted in the painting, a natural result of the medium, even if Kauffman does not append the motto. However, the most obvious similarity between the two are the ‘two little Wings on her Head’, showing ‘Elevation of Intellect’. The ‘image of Nature’ is completely different, though. The woodcut is hard to read, but it is meant to be an image of the Diana of Ephesus, reaching out her arms, just as Invention does. In its original form it is an image of fertility, with many breasts (see below). This was presumably chosen as an illustration of the fecundity of nature, from which we can draw inspiration, which in itself will lead to invention. Kauffman instead chooses a celestial globe, a view of the heavens, which would seem to speak of divine inspiration as much as drawing on the natural world. Unlike both the woodcut and the description, Kauffman’s Invention only has one arm naked – and there is no ‘cuff’, or second motto. The woodcut illustrates two columns, which are not mentioned in the text, and, like Kauffman’s image, has distant mountains on the far right. Kauffman’s choice of two trees (rather than columns) would seem to make sense, and could imply that the background, as much as the object held, might be seen to illustrate ‘The Image of Nature’.

There is, of course, a contradiction at the very heart of Kauffman’s painting, but it is one that is embedded in Ripa’s own work: NON ALIUNDE – ‘not from elsewhere’. Clearly, anyone drawing on Ripa’s idea is taking something from elsewhere, so it is not inventive. Does it even make any sense, therefore, to include this painting at the beginning of Now You See Us? You could argue that Kauffman was not being at all inventive – but then, when commissioned to paint Invention, what else could you do? I would argue, as the title of this post suggests, that necessity was the mother of Invention: where else would you turn, other than a readily available source of almost any personification you might be asked to paint?

However, not only was she using someone else’s idea, but she was relying on the work of a man. I state it like this because it would really agitate some writers on art made by women. I remember reading a social media post some time ago which berated Tate Britain for stating, on one of the gallery labels, that the work of Marlow Moss, an artist working in Britain in the first half of the 20th Century, was influenced by that of Piet Mondrian. Why should the work of this notable, but neglected woman be directed back towards that of a far more famous man? Could her work not be seen in its own right? To be honest, I can’t remember the exact phrasing used. However, what this particular (and now well-known) commentator had not noticed – or was deliberately ignoring – was that in the same room it was also stated that Ben Nicholson’s work was influenced by that of Piet Mondrian. So, my question would be, should only men be influenced by other men? And does this imply that women have to rely on their own ideas, or are they allowed to take inspiration from other women? Or, and this would be my suggestion, is it maybe that both men and women are part of an artistic community which is a community quite simply because it does have ideas in common? After all, it wasn’t just Angelica Kauffman who relied on the Iconologia of Cesare Ripa. Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory of Painting (also in Now You See Us) is drawn from it – but then, as she was also a woman, maybe that’s not such a good example. However, Vermeer’s Art of Painting uses Ripa’s Clio (the muse of history), while his Allegory of Faith draws on more than one of Ripa’s suggested qualities. And then, there is also this painting, which I saw by chance in the Accademia when I was in Venice a few weeks ago:

Pierantonio Novelli’s Il Disegno, Il Colore, e l’Invenzione (or Drawing, Colour, and Invention) is dated 1768-69, ten years before Kauffman’s four Elements of Art, and (coincidentally) exactly the date when the Royal Academy was founded. But then, it’s a very academic idea. If we compare Novelli’s Invention to the version by Kauffman, something should become quite clear.

Saying that Kauffman relied on the ideas of others does not, in any way, belittle her achievement, or make her less of an artist. It shows that she was part of an artistic community, and operated within that community in the same ways that her male contemporaries did. Indeed, one of the definitions which helps us decide what constitutes a work of art is that it is aware of its status as an art object. In other words, it acknowledges the work of other artists. I’m fairly sure that this is another feature of Kauffman’s image. The pose of Invention is not unlike many of Michelangelo’s seated figures, and is ultimately related to the Torso Belvedere, which features in Kauffman’s Design (again I would direct you to Day 48 – Colour and Design). The two trees on the left are also relevant, I think, given that they remind me of those growing in the background of Titian’s Death of St Peter Martyr, which was widely copied and quoted before its destruction by fire in 1867.

I think we should be more specific about the extent to which Kauffman is reliant on Ripa. Her image of Invention is not the same as Novelli’s, which, like the woodcut above – and every other illustration from different editions of the Iconologia I have seen – shows the ‘Image of Nature’ as the Diana of Ephesus. Kauffman is not copying ideas mechanically, and, for whatever reason, she chose a celestial globe instead of the Diana. She also set Invention within an entirely natural setting, rather than including any architectonic elements. In some ways, therefore, she was actually more inventive than Novelli. She was also, undoubtedly, part of an artistic community – indeed, she was part of several. For these reasons, and more, the painting really is a perfect introduction to Now You See Us.