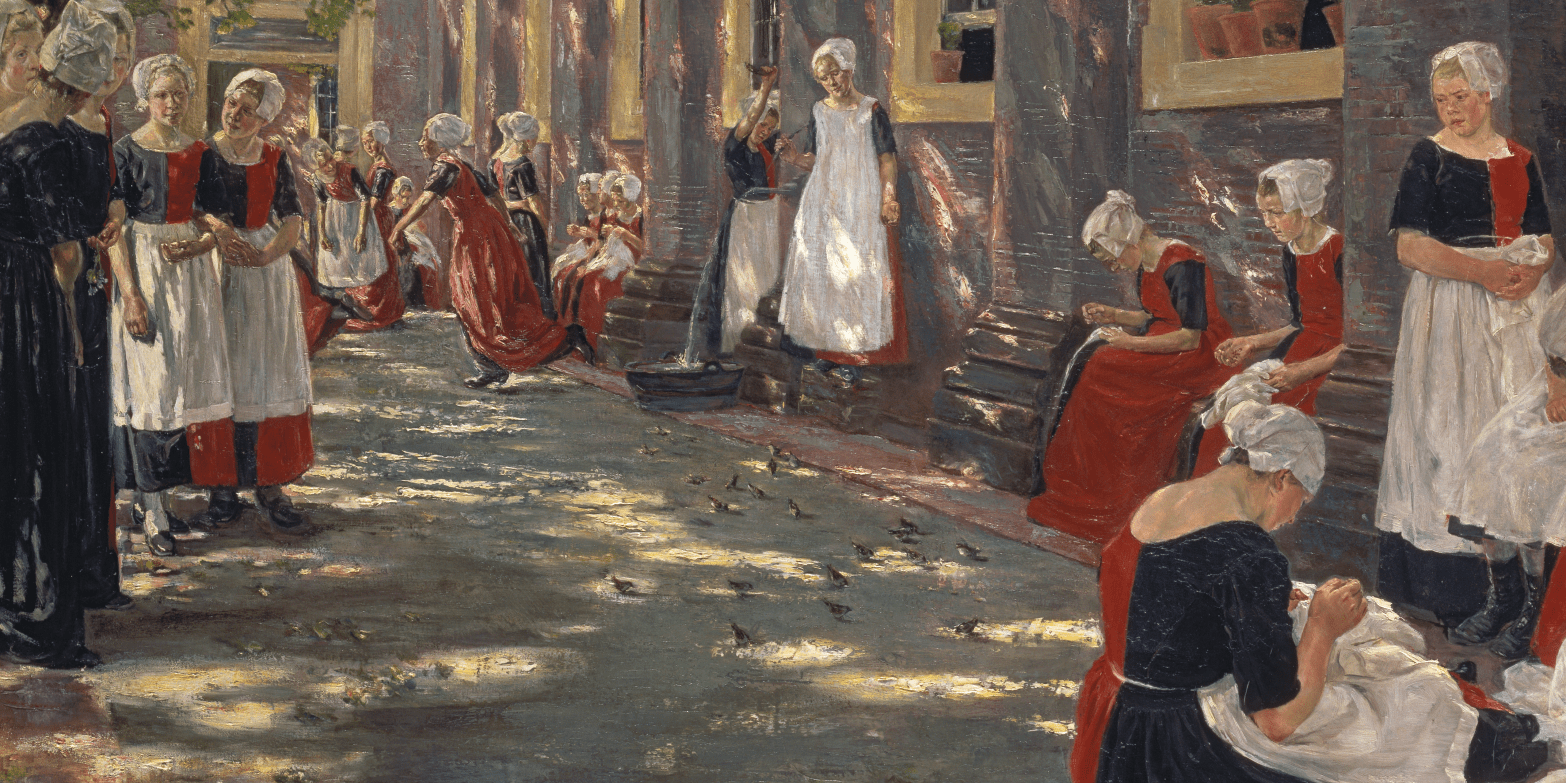

Max Liebermann, Free Time in the Amsterdam Orphanage, 1881-82. Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

German Impressionism – the subject of my talk on Monday, 19 May – was not a direct rejection of the pristine surfaces and clear, crisp colours of the Nazarenes, who I talked about earlier this week, but it so easily could have been. With Max Liebermann’s paintings, one of which I will be writing about today, we are instantly into the world of rich colour and spontaneous brushstrokes, with all the evidence of capturing the moment and self-conscious making of art that French Impressionism entails. However, we are in a rather different world. During the talk we will look at the way that Liebermann and his contemporaries used the lessons of French Impressionism to take their work in a different direction, and to create paintings which had fundamentally different ideas. The following week (26 May) we will look at the wonderfully emotive sculptures of Ernst Barlach, and use them to think about the nature of Expressionism. I’ve then changed my plans – but fortunately before I’d put anything else online. I was so bowled away earlier this week by the remarkable, inventive, intricate and even surreal drawings by novelist and poet Victor Hugo that I want to have a good look at them while there is still time for you to get to the exhibition at the Royal Academy – it closes on 29 June) – so I will introduce that on 2 June. Many of the drawings belong to the Maison Victor Hugo in Paris, where another private residence, now the Musée Jacquemart-André, is hosting an Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition which runs until 3 August – so there’s a while for you to plan a little jaunt to Paris should it take your fancy! I will talk about that on 16 June, and then on 23 June I will look back to Cimabue – and this is ‘looking back’ in more ways than one. First, I’m afraid that the exhibition at the Louvre (which I saw last week) has already closed – but the talk will give us a chance to reconsider what was there. Second, it looks back before Duccio. Had I managed to time things better, the Louvre’s exhibition would have been a perfect introduction to Siena: The Rise of Painting – which you can still see at the National Gallery. Following on from Cimabue (or even, starting with him) I will end my ‘summer season’ with three talks about the new hang of the Sainsbury Wing in the National Gallery. Keep an eye on the diary for more information!

A large number of girls are gathered in a courtyard, wearing a uniform that is almost identical throughout: a long dress with short sleeves, red on the left and black on the right; a white headdress; and, for most, a white apron. The building is formal, with bold, brick pilasters framing large windows. A sweeping perspective pulls the eye towards the far wall of the yard, and a doorway framed in the same colour as the windows. On the left, the composition is closed by a line of trees, under which some of the girls chat. The leaves are light green, and sunlight passes through them to creates mottled pools of light on the floor and on the wall.

In the foreground on the right a group of eight girls are busy sewing. They are so focussed on their work that we could imagine there is total silence here. Some seem to be sat on the base of the architecture, and one is partially hidden by the strongly projecting pilaster in the foreground. With her left hand she lifts some white fabric, which is indistinguishable from her apron, if she is wearing one, while her right hand pulls back a needle, the thread just visible. Next to her another girl – who clearly is wearing an apron – reaches down to pick up some of the white material, with a third girl sitting on the ground in front of her looking down at her own work. Another girl sits sewing behind the one who is bending over, with a fifth peering down to see what she is doing. Two more sit in the next bay, between two of the pilasters, one of whom is more involved in sewing, while the other seems slightly distracted. However, she is still more involved in her work than the girl who is standing, framed by the pilaster which is second in from the front. She stands upright, her white cloth held with both hands in front of her waist, looking down over her right shoulder as if considering something on the floor – maybe the dappled pools of light. Further back the light falling through the trees hits the wall, and seems to take on the red of the girls’ uniforms. It also falls on the apron of the only girl I can see who is wearing an apron, or smock, hanging full-length from her shoulders, who is precariously perched on the base of one of the pilasters. Behind her another girl, half hidden, reaches up.

This girl is actually reaching up to pump water, the spout projecting horizontally to the left just above her waist. The jet of water that results is disguised, as it follows the outline of her skirt, but it must be there as you can see splashes of water above the broad, low basin on the ground: they are caught in the sunlight. Further back more girls sit and sew, while others stand and chat to them. Elsewhere there is more activity, with one girl running from right to left, the foot of another, curved up in a similar way, just visible: they are chasing one another. There also seems to be more conversation taking place in front of the doorway in the distance. Maybe some sound will reach us from the far side of the courtyard: a buzz of conversation, the footfall of the running girls, maybe the occasionally shout, the splash of water. Nearer to us, on the left, two girls walk arm in arm, and others turn to each other in conversation. High up on the right, attached to one of the pilasters, is the curved bracket of a lamp, the sunlight glinting from the glass of the lantern. The top left of the painting is filled with the trunks, branches and bright green leaves of the trees, their light colour enhanced by the sunlight, yes, but also suggesting that we are probably some way into spring, but by no means at the full height of summer, by which time they would be darker. This precision of detail, the spontaneity of the movement, and the accuracy of the interactions and of the intense focus on the needlework suggests that the artist, Max Liebermann, was there, capturing the essence of the scene as he saw it – but this is all artistry. It might come as quite a surprise to learn that the trees were not there.

This is a sketch of the courtyard – and of the girls – which Liebermann made when he was in Amsterdam in 1876. This was the year of the second Impressionist exhibition in Paris – the first had been in 1874. Like one of his French contemporaries, he was painting ‘en plein air’ in front of the ‘motif’. Or, to put it another way, he was outside painting what he saw, capturing the moment. Born in Berlin in 1847 (he was seven years younger than Monet, so of the same generation), he went to art school in Weimar at the age of 22, and travelled widely, often to the Netherlands. In 1873 he moved to Paris, and spent the summer of 1874 in Barbizon, which could be considered the ‘capital’ of of plein air painting… He was in the right place at the right time, you would think. However, his art continued to align itself more with Realism – effectively painting the things that concern real people, rather than saints or deities, miracles or myths. He made return visits to the Netherlands in 1875 (when he spent a long time inspired by the broad brushstrokes of Frans Hals) and 1876 (when he visited the orphanage in Amsterdam), and settled in Munich in 1878 after meeting a group of German artists in Venice. However, it wasn’t really until 1880 that his style shifted towards Impressionism. In Amsterdam once more, he visited the Oudemannenhuis (the ‘Old Man’s House’), where the men, dressed in black, were sitting in the garden, and light was filtering through the trees. The effects of this light were a revelation, and Liebermann later said that it felt “…as if someone were walking on a level path and suddenly stepped on a spiral spring that sprang up.” It was this that inspired him to paint what became known as “Liebermann’s sunspots” – like the ones we can see in today’s painting. The difference in style is clear, especially when compared to the sketch.

The finished work has tall trees on the left of the path, with bright sunshine filtering through to create sunspots on the floor, on the walls and on the girls’ dresses and aprons. The sketch, from the Kunsthalle, Bremen, does not have these sunspots – but then, there are no trees in the sketch for the light to filter through, just a couple of bushes. It doesn’t even look like a sunny day. Quite the opposite, in fact – it could be grey and overcast. The sketch is signed, and clearly dated 1881 – but Liebermann must have painted it in 1876, when he was there. By 1881, when the finished painting was started (in his studio in Munich) his style had changed substantially – but for whatever reason, that was the date he gave to the sketch. Over the years he based a number of works on the sketches he had made in 1876. In many ways, therefore, he wasn’t an Impressionist at all, trying to capture the ‘sensation’ he first had on witnessing this scene. He may have painted preparatory sketches en plein air, but he developed them later, back in the studio, adding trees, changing the weather, inventing the dappled sunlight… Having said that, the French Impressionists weren’t always as spontaneous as you may have thought – just think of Monet, completing his Thames views during the three or four years after he had visited London. Is has been said, with some degree of justification, that some of the artists (Degas, for example), rarely, if ever painted outside anyway. This is art, though – does it really matter? And even if he invented the trees, and the sunlight, Liebermann’s depiction of the building itself was entirely accurate. We can tell that because it’s still there: here it is with a detail of Liebermann’s painting.

The Amsterdam orphanage – the Burgerwaisenhaus – had its origins in 1520, and moved to this location sixty years later. The ‘Burger’ is important here. It wasn’t an orphanage for the poor, nor were there any foundlings. These were the children of citizens who had been orphaned – effectively the children of the middle-classes – and there were boys as well as girls: we just happen to be in the girls’ courtyard. Plagues and epidemics in 1602, 1617 and 1622-28 had substantially increased the number of orphans, and 1634 the orphanage – which was originally housed in a medieval monastery – was enlarged. This building was probably designed by Jacob van Campen, who was also responsible for Amsterdam Town Hall (now the Royal Palace), and the Mauritshuis in The Hague, among other notable buildings. When Liebermann visited in 1876 the children still wore these uniforms in black and red – the colours of the Amsterdam coat of arms – and would continue to do so until 1919. The orphanage itself staid put until 1960, at which point it was transferred to a new building, which is said to be a modernist design classic. Since 1975 the 17th century building has been the home of the Amsterdam Museum, with the adjoining boys’ courtyard now used as an open-air café.

I’d like to finish by returning to one of the details of the painting: the one distracted girl in the right foreground.

It wouldn’t be true to say that any of the girls here look happy, but they do at least look engaged. All of them, that is, apart from the one standing up. She holds her fabric to her stomach and looks down over her shoulder. To my eye she looks unequivocally Dutch, but I’m probably relying on broad-brushstroke stereotypes. However, she does look melancholy: what is prompting this reflection? What is she looking at?

The direction of her gaze isn’t entirely clear, to be honest, and it could be that she isn’t looking at anything at all, just lost in her thoughts. But if she is looking at the floor, then maybe she is mesmerised by the sunspots, created in the painting with thickly impasto-ed strokes of white and cream-coloured paint. Or maybe she is fascinated by the sparrows, pecking away at whatever they can find, gleaning a meagre existence from anything that has fallen from the trees, or has been dropped by the children. There is no evidence of them in Liebermann’s sketch: were they really there? Or is he trying to say something allegorical about the situation of the orphans, gleaning a meagre existence from the charity of others? Being who I am, my mind instantly turns to two passages from the Gospel according to St Matthew. Chapter 6, verse 26 says, “Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they?” Meanwhile, in Chapter 10, verses 29-31, we read, “Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? and one of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father. But the very hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear ye not therefore, ye are of more value than many sparrows.”

It’s possible that these verses are relevant, although it is worth noting that Liebermann was Jewish. Given the increase in secularism over the 19th Century, the gospels were probably not standard reading for many artists at the time, and it would have been even less likely for Liebermann. However, he had painted two versions of The Twelve-Year-Old Jesus in the Temple just a couple of years before: such situations are never as straightforward as you might think. Changes in the Prussian law regarding Jews benefitted him as a child, but as an old man he suffered professionally – as so many did – with the rise to power of the National Socialists. However, his death in 1935 – at the age of 88, and from natural causes – meant that, although a broken man, he was not a victim of their worst atrocities. Inevitably we will touch on this on Monday, although the majority of the time will be spent looking at his paintings, and those of his fellow German Impressionists, as we discover what the implications of that term really were.

Thank you so much for your detailed explanations, especially your reference to the depicted sparrows and the two biblical references. The gift of being alive without being obliged to “earn” it or fill it with labor and hardship. Don’t we, living in modern societies, quite like the C19 girls depicted in the foreground, often struggle too hard with our own activities and forget to simply enjoy the gift of a beautiful spring day? But in the background, girls chasing one another are having fun!

If your journey ever takes you to Berlin, I recommend a visit to the Liebermann Villa in Wannsee, if you haven’t already. It was Liebermann’s summer residence since 1909, long after he had painted the Dutch girls. An upper-class ensemble, not just a garden house. It’s now a museum with temporary exhibitions by other artists and has a pleasant terrace café. The garden is a listed ensemble and has been reconstructed as Liebermann had designed it. There, one gets an idea of how wonderful a bourgeois life as a prince of painters must have been during the Belle Époque. His life must have been happy before the dark years came in his old age.

LikeLike

Thank you, Petra – and thanks for the suggestion! I’d love to visit the Lieberman Villa – I will show at least one of his paintings of it on Monday – but who knows when I’ll ever get to Potsdam? I’ve been a couple of times (to Potsdam, but not the Wannsee), but only in the winter. There’s so much to see there it really deserves a visit on its own, even if Berlin is just next door!

LikeLike