Carlo Crivelli, The Vision of the Blessed Gabriele, probably about 1489. The National Gallery, London.

One of the most dramatic vistas I’ve ever seen in a museum is new – and it is one of the splendours of the new hang of the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in London. Indeed, I’ve been using a photograph of it to advertise my talk this Monday, 7 July at 6pm, the Second Sainsbury Story, At home in the Church. We will look at the ways in which the arrangement of the paintings can help us to understand the context in which they would have been seen when first painted. We will also discover the ingenious ways in which one room is linked to the next. The work I want to explore today is part of the progression through this series of rooms, and it responds to the Crucifix hanging from the ceiling with a vision of the Virgin and Child which can appear to be – if you look at it the right way – in our own space. You’ll have to trust me on that – or read on, to find out what I mean. The third ‘story’ will look at paintings from across the Italian peninsular which were made either for domestic spaces – and these could be religious or secular paintings – or for churches. Sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference, but join me on 14 July for Sainsbury Story 3: In Church and at Home for a few pointers. As an example of this idea we’ll start (probably) with Piero della Francesca, who painted a Nativity for his own domestic devotions. After that I’ll be on holiday for two weeks, returning for Seeing the Light: the art of looking in and around Duccio’s Maestà on 4 August. I’ll then be acting in Sidmouth for a couple of weeks, but plan to give a talk on 25 August, the next in my (very) occasional series A stroll around the Walker, looking at works in my ‘local’ museum, The Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. This will be my fifth visit, and will focus on the 18th Century, and I will post more information about this in the diary by Monday evening.

We see a Franciscan friar kneeling on barren, stony ground in the left foreground of the painting. He looks up to the right, towards a vision of the Virgin and Child, who are apparently hovering in the top right corner. A garland of fruit is slung across the top of the painting, although it is not at all clear how the garland is attached. On the left the landscape rises up as a steep cliff of red, curving rocks, balanced on the right by a renaissance-style building with a dome on the higher section and semi-dome on what could be an apse. This is Crivelli’s representation of San Francesco ad Alto, which in ‘real life’ was – and is – a substantially larger structure, originally in the countryside outside the city walls of Ancona in the Marche. Apart from the fact that the city has expanded, so that the building is now in the suburbs, the church was secularised in 1863 and what was the priory is now home to a military base. However, its origins are are supposed to go back to the founder of the Franciscan order, St Francis himself. He is believed to have designated the site of the priory in 1219 when he was passing through Ancona, using the port as a point of departure for his pilgrimage to Egypt (we’ll see Sassetta’s painting of what happened when he got there on Monday). Gabriele Ferretti – the subject of today’s painting – was the Superior of the priory for three years, starting in 1449, and continued to live there until his death in 1456. Like St Francis he came from a wealthy family, but gave up that wealth to join the Church. He became renowned for the sanctity of his life, and for his regular retreats to the woodland surrounding the priory to pray and to meditate (much as St Francis had done). It was there that he experienced visions of the Virgin and Child. After his death his family sought to have him canonised (recognised as a Saint), but the miracles were never forthcoming. However, he did get as far as being beatified – the first step on the road to Sainthood – although that didn’t happen until 1753. Initially buried in a simple grave outside the church, in 1489 his body was transferred to a marble tomb monument (commissioned by his sister Paolina, one of the rare examples of female patronage) with today’s painting hung above the effigy of the deceased.

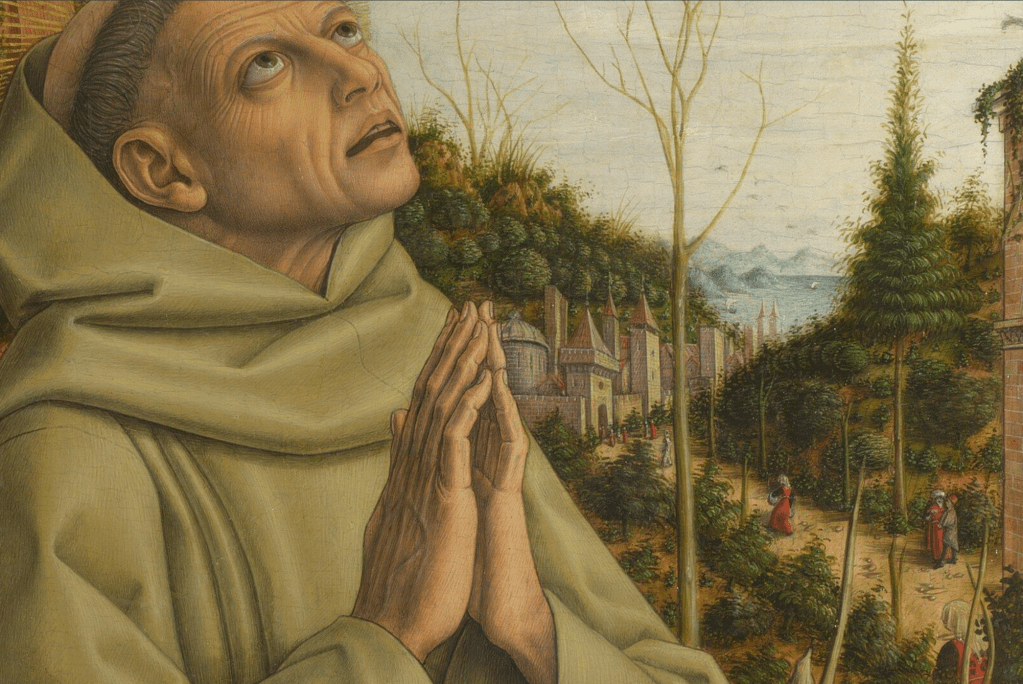

I wanted to start by getting in close to give you a sense of where we are. The strength of Ferretti’s devotion is made clear by his bright, wide-open eyes, apparently looking directly upwards. They shine with bright catchlights, which make him look both alert and fervent. His mouth is open with a sense of dumb-struck awe, which helps to convince us about his feelings on seeing the divine vision. In the very top left corner of this detail a few golden beams are visible, radiating from his head. These are often given to the beatified in advance of their full canonisation, at which point they would get a full halo. However, Crivelli has included this beatific radiance some 160 years before he achieved the relevant states – but this was something he did at the family’s request, and with the permission of the Franciscan order: they too would have welcomed a newly canonised Saint among their number. Crivelli’s clear understanding of the structure of the Franciscan habit is marked by the precise delineation of a seam between the neckline and Ferretti’s praying hands, as well as another at the top of his right sleeve: delicate details which add to the image’s authenticity. Just to the right of his fingers – and some distance away – we see a walled city. This is a stylised representation of Ancona, suggesting that we are out in the countryside, some way from the city walls. This makes sense, as this is exactly the sort of place where St Francis wanted his followers to live – and where the priory was in any case located. Further away we see the sea and the coastline, with hills forming promontories reaching out into the blue water. This is a fairly accurate evocation of the coastline of the Marche: we are looking northwards, towards Rimini, Ravenna, and eventually Venice. There are people chatting to one another on the road which winds its way through the sparse trees of the wood, while others come and go, to and from the city, their size dependent on their distance.

If we take a step back we can see that the priory is next to this road. The cave on the left of this detail may have been intended to stress Ferretti’s humility – as if it were an even humbler place to retreat – while the perspective of the church leads our eyes towards the holy man. As he looks up a line of birds flies on a similar diagonal to his gaze. Stepping back further, we would see how this could lead our eyes to the vision. Just beyond Ferretti’s left elbow is the hooded head of another Franciscan, included to enhance the connection between the subject of the painting and the order’s founder. No one had painted The Vision of the Blessed Gabriele before, so how was Crivelli supposed to know how to do it? Presumably by looking at a similar subject. He seems to have based his composition on another which was far more common: The Stigmatisation of St Francis. Here’s a comparison with Sassetta’s version of the Stigmatisation (which will also find its way into Monday’s talk).

Francis has gone out into the countryside to pray, and sees a vision of a winged seraph. One of his followers, a Brother Leo, has accompanied him, and although reports suggest that he did not see the vision, he is often included in the paintings anyway. Usually, though, he is some way off, and often on the other side of a stream. However, Sassetta makes him far more prominent. As well as going out into the countryside to pray – and experience a vision – Gabriele Ferretti, like St Francis, has also been accompanied by one of the other brothers, although we can only see his head. This stress on the similarities between the two may well have been suggested by the Ferretti family, the patrons of the painting, or by the Franciscans of the priory, in the hope that this would speed up the process of canonisation. Francis’s followers named him Alter Christus – another Christ – and in this painting Crivelli shows us Gabriele Ferretti as Alter Franciscus.

The artist encourages us to believe what we are seeing by including some highly realistic details, which not only catch our attention but also draw us in. In the left foreground is the edge of a stream, or just conceivably a pond. We could think about the water of life, or baptism, I suppose – the religious setting would favour such an interpretation – but it is more important for the beautifully painted detail of the duck and duckling, with an excellent distinction between the mature feathers of the former and soft, fluffy down of the latter. The delight we might take at the accuracy of their depiction helps to pull us into the space of the painting, keeping us involved and maybe even encouraging us to seek out other such details. They also help us to trust anything else we see as real. For example, there is a rubricated prayer book (some of the pages are written in red) lying open in front of the kneeling friar. Next to it, the artist’s signature is foreshortened, as if lying on the ground: OPUS KAROLI CRIVELLI VENETI – the work of Carlo Crivelli from Venice. Although Venice played a relatively little part in his career, it was a good place to come from as an artist: a mark of his superior status. Behind Ferretti’s feet are his sandals. Like Moses before the burning bush (Exodus 3:5) he has taken off his footwear because he is on holy ground.

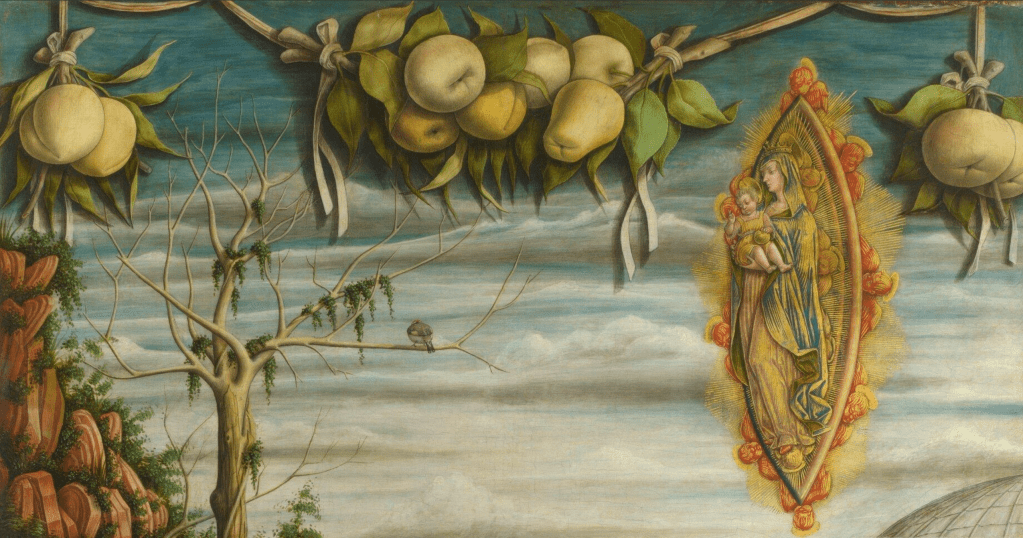

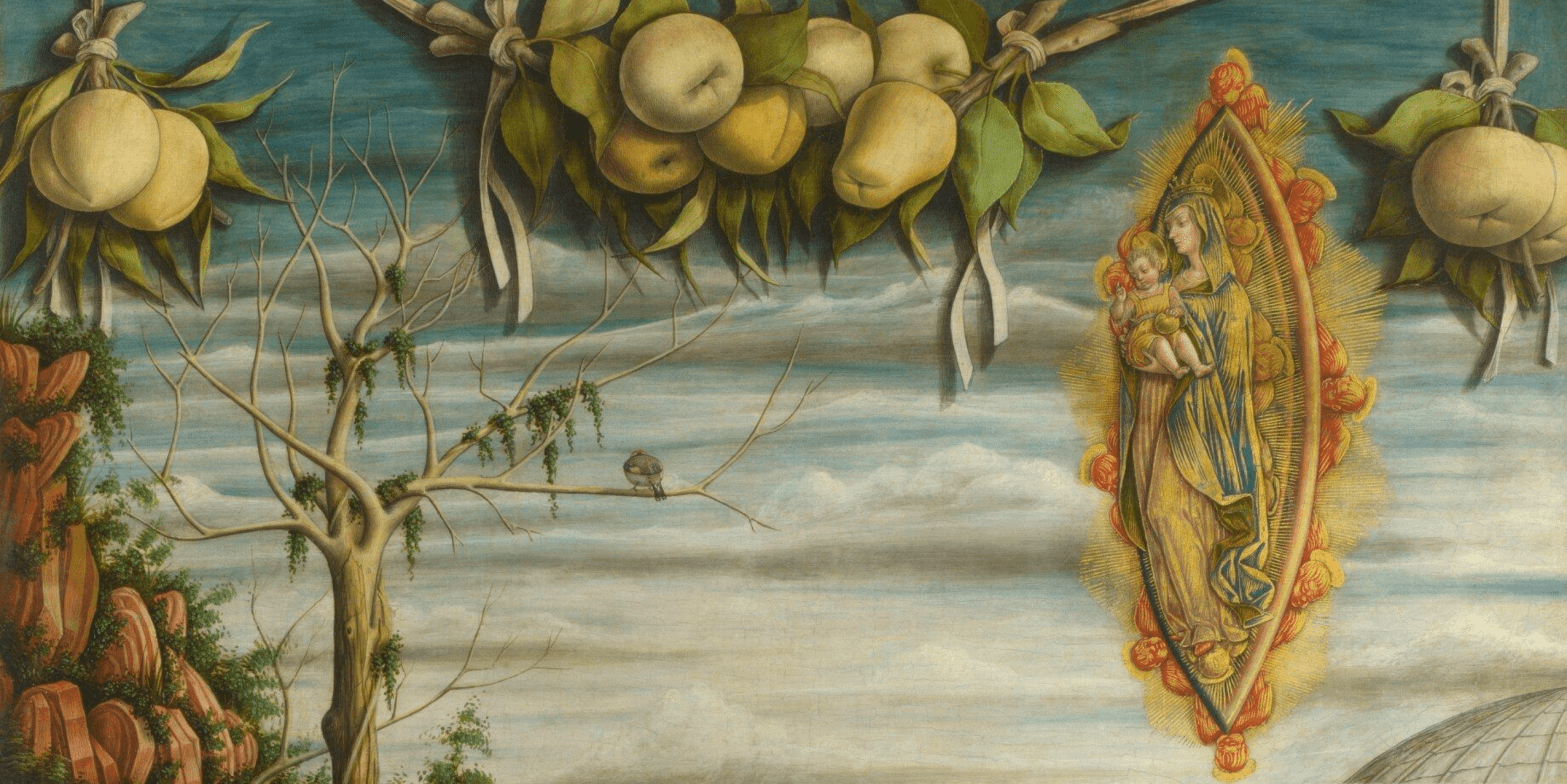

When we look up, following his gaze – and the line of birds – we can see why he considered it to be holy. Just above the church there is a mandorla. The word means ‘almond’, but is used to describe the geometric form which so often surrounds figures appearing in visions – in part, because this was the shape of the structure on which actors would appear (or disappear) when representing holy figures in religious dramas. The arrival of the Archangel Gabriel at the Annunciation, for example, or the Ascension of Christ or Assumption of the Virgin would all use such mechanisms.

The mandorla itself is at an angle – which is unusual. Every other one that I can think of is placed frontally – a formal arrangement which makes it clear that the vision is intended for us, the viewers of the work of art. However here the vision is the Blessed Gabriele’s, and the Virgin and Child are angled towards him. Indeed, Mary holds the child high in front of her chest as if she is about to hand the baby to Ferretti, offering him the chance to hold the divine. Mary and Jesus both have haloes, as do the winged heads of the red seraphim whhich surround not only the mother and child, but also the mandorla, supporting it on its miraculous descent from heaven. The religious figures are radiant with applied gold, and beams of light shine out on all sides, equivalent to Gabriele’s own radiance. This rich and detailed use of gold helps to make the vision stand out from the background, with its sky streaked by numerous clouds in shades of white and grey. The mandorla is neatly framed by the bunches of fruit which make up the garland. The stalks of some of the fruits are tied with pink ribbons, which hang from something unseen at the top of the painting. The mandorla is balanced on the left side of the painting by a tree which reaches more or less the same height. Notice how remarkably horizontal two of the branches are – one reaching to the left, and another to the right – while a third branch rises almost vertically. It is no coincidence that this tree has taken on the shape of the cross: the bird, sitting with its back to us, confirms that this was the intention.

Admittedly it’s not that easy to see, even in this detail, but it has flashes of yellow on its wings, and a splash of red on its head: this is a goldfinch. Jesus was grasping one upside down in last week’s painting, the newly acquired Netherlandish or French Virgin and Child with Saints Louis and Margaret. According to legend, the red colour came from the blood of Christ, which dripped onto the head of one of the ancestors of this little bird when it plucked a thorn from Jesus’s forehead on the way to Calvary. The goldfinch is a symbol of Christ’s Passion – and confirms that the cross shape evoked by the branches of the tree do indeed refer to the crucifixion. But there’s something more surprising than that here. At the top of this detail you can see some of leaves of the fruits, and the ends of one of the ribbons with which they are tied – and they do something unexpected: they cast shadows on the sky. Of course, they are not casting shadows on the sky, they are casting shadows on the painting – of which they themselves are a part. Crivelli is suggesting that this image is so important – given that Ferretti himself was – that it has been decorated, with the garland intended to honour the Blessed Gabriele. It is a remarkable trompe l’oeil invention which shows us how sophisticated the artist was, despite his apparently retardataire (i.e. old fashioned) use of gold. But that’s not all.

Some of the golden beams of light which emanate from the mandorla on the right seem to pass in front of the shadows. And if the shadows are cast on the painting, then the vision, with the mandorla at an angle and the Virgin and Child sculpturally in front of it, must be in front of the painting. Jesus and Mary are painted as if physically in our space. This illusion – with part of the imagery apparently in front of the painted space – would probably have been more convincing when the work was in its original location which, even during the day, would have been the fairly dark interior of a church.

On entering San Francesco ad Alto, the painting would have been in a corner, opposite the door through which the worshipper would enter, but to the left. It hung above the effigy of the deceased lying on his sarcophagus (this section the monument survives in the Diocesan Museum in Ancona). As a result we would have seen the painting, initially at least, from the bottom right. This is why the signature is foreshortened as it is, and would have emphasized the way in which the book leads us into the space. The top of the painting would have been fairly high, and what little light there was would have caught two parts of the image in particular, the two areas which were gilded: the Blessed Gabriele’s radiance, and the rich glory covering and surrounding the Virgin and Child. With the vision glowing in the darkness in front of the grey cloudy sky, it would surely have enhanced the sensation that the mandorla was floating above the deceased, in our space, and that the Virgin and Child were watching over the carved effigy as much as the painted image. If they turned their heads to their left, they would have seen us standing there too. Given this, the new placement of the painting in the Sainsbury Wing is especially brilliant.

Hung like this, we approach with the painting on our left, as we should. Gabriele Ferretti kneels in prayer in front of the miraculous vision, which hovers in the space of the Sainsbury Wing about a quarter of the way between the revered Franciscan and Segna di Bonaventura’s Crucifix hanging from the ceiling of the adjacent room. It really helps to enhance the apparent solidity of the mandorla, and of the Virgin and Child. This is the sort of connection within the rooms and from one room to another which I will be discussing on Monday. Having said all of that, I might have been getting carried away the last time I saw the Crivelli. I couldn’t help but marvel at his skill, and his remarkable ability to create the most unbelievable sense of three-dimensional illusion. It even looked as if he had gone so far as to evoke a genuine Franciscan stepping forward to greet the Blessed Gabriele in front of the painting.

I absolutely loved reading this. I really like this painting. It reminds me very much of the predella in Crivelli’s Madonna della Rondine and the St. Jerome depiction.

Fiona Marshall

LikeLike

Thanks you, Fiona – I’m glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

Refers to talk on Monday evening re part of NG rehang. Shall I book? P

LikeLike

By all means, please do! Although I suspect you meant to send this to someone else…

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Dr Stemp, for your marvellous commentary on this beautiful painting. I look forward to your talk this evening. I have no immediate plans to visit London so it’s wonderful to visit the new Sainsbury Wing with you online!

Best wishes,

Eithne White.

LikeLike

A great pleasure! Thank you for joining me!

LikeLike

We are on a short visit to London . Enjoyed reading this whilst in front of the painting . You make me see ! Thanks

LikeLike