Joseph Wright of Derby, Three persons viewing The Gladiator by candle-light, 1765. Private Collection, on long term loan to The Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

As my next talk, on Monday 25 August at 6pm, will look at the 18th century art in the Walker Art Gallery I thought that today I would think about one of the paintings which is on long term loan to the Gallery, even though it isn’t currently on show there. That’s probably because I’m sure it will be included in the National Gallery’s exhibition Wright of Derby: From the Shadows which will open in November (it would certainly fit the title), and it may have gone for some preparatory checks. We’ll find out nearer the time, of course, and as I will be talking about the exhibition when it opens I’ll be able to let you know. The Walker has a great collection of Wright’s paintings of its own which are on view, though, as well as a representative selection of works by Stubbs, Hogarth, Gainsborough et al – not to mention a number of great works which are not British – and my fifth Stroll around the Walker will cover as many of these as I have time to include.

Down here in Sidmouth (and thanks to all those of you who have come to see the shows!) I have had time to timetable the six subsequent talks, four of which are already on sale. Rather than a description, here’s a list: I thought it would be clearer. You can find more information via these links, or from the diary.

15 September, Good Times – The ‘Très Riches Heures’

22 September, The Duc du Berry: the man himself

6 October, Fra Angelico 1: A Melting Pot

20 October, Fra Angelico 2: As seen at the Palazzo Strozzi

And on sale on 6 October will be

27 October, Fra Angelico 3: At home in San Marco

3 November, Fra Angelico 4: Students and Successors

But, as I always say, keep an eye on the diary for more… Meanwhile, back to Joseph Wright.

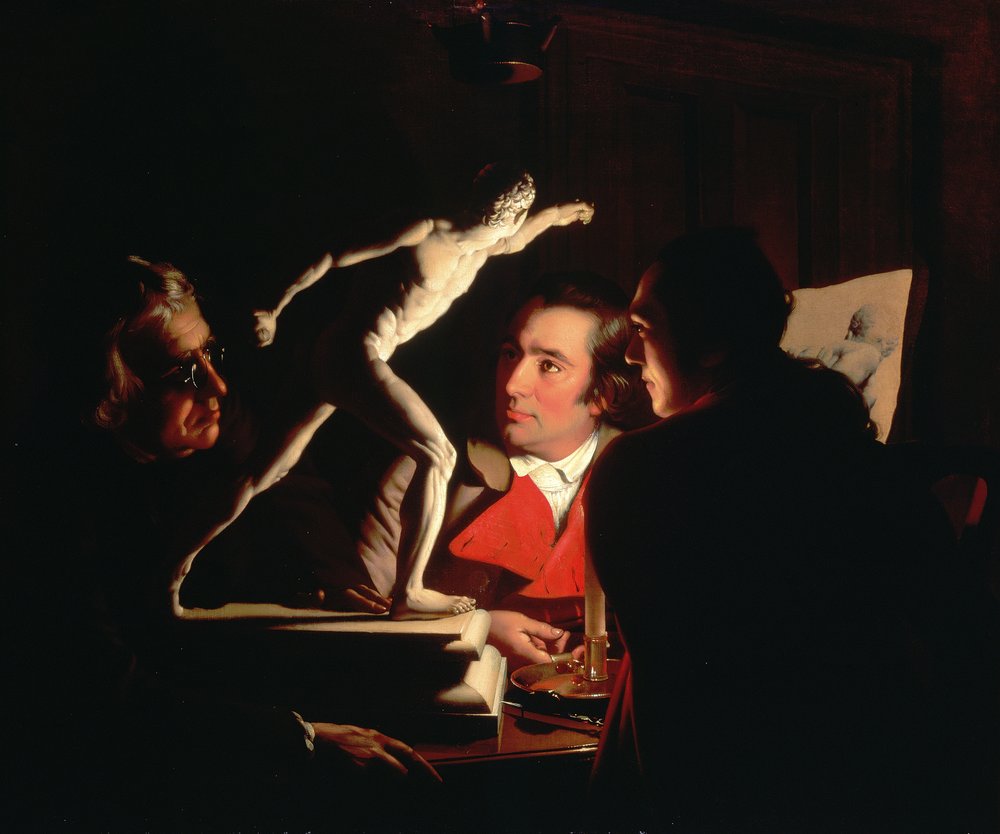

We can see the ‘Three persons’ of the title quite clearly, even though the room in which they are sitting is very dark – pitch black, even, in this reproduction. There is apparently only one light source – a candle – which illuminates the scene. The faces are seen from different points of view, and, given that the candle is in between them (although not central) each face is illuminated to a different degree and from a different angle. The Three persons are arranged around The Gladiator, a white sculpture of a man lunging forward on his right leg, with his left arm extended in front of him and his right held behind. On the right side of the painting is a piece of paper which includes an image – a drawing or print – which shows the sculpture from a slightly different point of view.

This is one of the first of Wright’s candlelight paintings, the genre which will form the subject of the National Gallery’s exhibition. The most famous examples are An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump of 1768, and A Philosopher giving that Lecture on the Orrery in which a lamp is put in place of the Sun, which was painted the following year. Today’s painting precedes them both by at least three years, as it was first exhibited in 1765. Although they all seem to be so obviously inspired by the work of Caravaggio, it is not entirely clear if Wright had seen the Italian artist’s work by the time these paintings were made: he didn’t travel to Italy until the end of 1773, some five years after the last was painted. He was in Rome from February 1774 to June 1775, and would finally have had ample opportunity to view the celebrated paintings by the master of chiaroscuro – ‘light and dark’. Previously, he may well have had access to prints – although they would have been monochrome – but he might also have been inspired by the work of Rembrandt (who never left the Netherlands) and the Utrecht Caravaggisti, the Dutch artists who travelled to Rome and studied the paintings of Caravaggio around the time of his death in 1610 and shortly after.

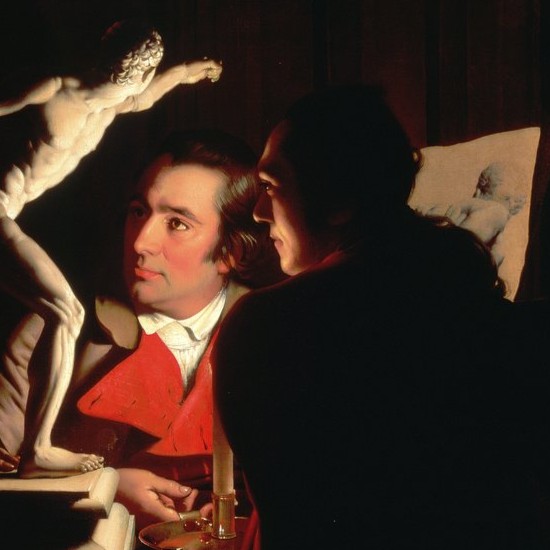

One of the problems of discussing this painting today is that it is very difficult to photograph – if you can capture the full depth of the darkness, as the above image does, you also lose some of the subtler details. So here’s a different photograph.

This one is far more obviously an image of a physical object – you can see light reflecting off the painting, revealing brushstrokes and the craquelure of the surface. The colours appear lighter, and brighter, which allows you to see details such as the lamp hanging from the ceiling more clearly. The lamp constitutes a second light source – but sheds so little light on the scene as to be all but irrelevant. However, it does help to remind us that these men are inside, in a room with a ceiling. However, the darkness was probably not originally quite so intense: while some pigments fade, others darken… In order to differentiate the details of the background, as well as comparing different photographs of the original, it can be helpful to look at a contemporary print.

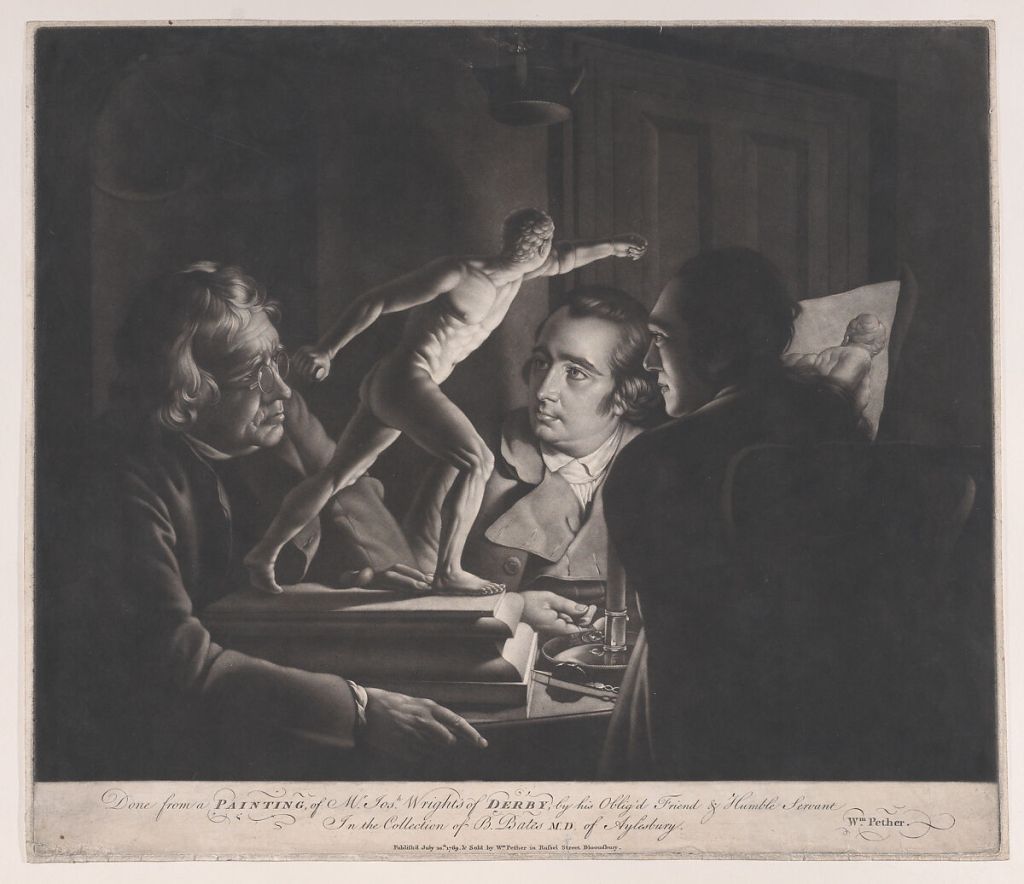

This one comes from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was published in 1769 (just four years after the painting was exhibited) by the engraver, William Pether. Often engravers would consult the artist to make sure they were getting the details right. Engraving can be very precise, and it would help the engravers to clarify areas which are far more atmospheric in the painted original. As a result, they are often nowhere near as evocative as the originals – although techniques were developing which could help to achieve similar effects. To be entirely accurate, this is a mezzotint, a technique developed in the 17th century precisely to try and achieve some of the subtlety of painting. The copper plate was first stippled with tiny dots using a metal tool called a ‘rocker’, and then areas which should be light (and so not pick up ink) would be burnished smooth. This technique enabled printmakers to achieve a far more subtle variation from light to dark, and, with fewer hard edges and firm outlines, approach the atmospheric blurring that can be achieved with oils.

The print is inscribed at the bottom ‘Done from a PAINTING of Mr Joseph Wright’s of DERBY, by his Oblig’d Friend & Humble Servant’ – which suggests that Pether had indeed been in discussion with Wright as to the nature of certain elements, and there are features in the background which are not visible in the painting. The older man on the left sits in front of a niche, while behind the two younger men on the right there is a door. I suspect that these details could be relevant to the meaning of the painting – but we’ll come back to that.

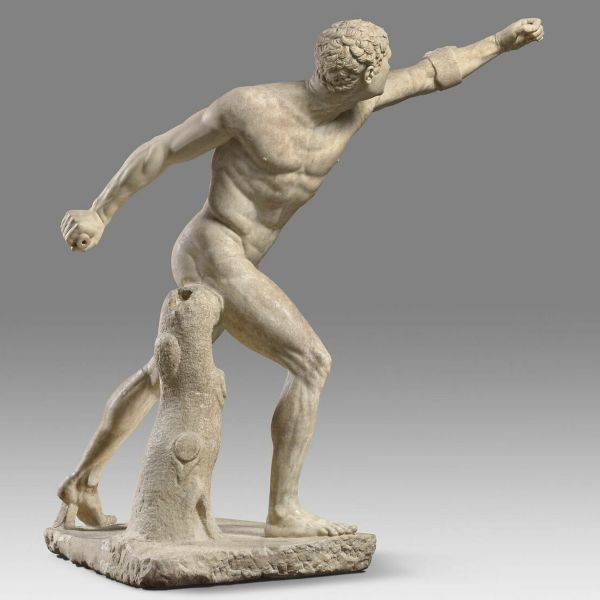

The sculpture which the men are viewing is a version of a marble known as The Borghese Gladiator. The original (on the right) is far larger than this painted version: at 173cm tall, it is effectively life-size (remembering that, were the man to stand up, the sculpture would be taller). Carved onto the tree-trunk is an inscription in Greek which translates as ‘Agasias, son of Dositheus, from the town of Ephesus’ – a sculptor who is otherwise unknown. It was found in 1611 in Nettuno, near Anzio, south of Rome, as the result of excavations commissioned by Cardinal Scipio Borghese. A later Prince Borghese was constrained to sell it to his brother-in-law – none other than Napoleon Bonaparte – which is why it is now housed in the Louvre. Despite being known – universally – as The Borghese Gladiator it is now known – universally – that the man was never intended to be a gladiator at all, but a warrior fighting someone on horseback – hence his upward gaze. The misidentification resulted in a number of ‘restorations’, adding some ‘missing’ details to make the subject clearer – but some of these (not the ones necessary for structural integrity) have since been removed. From the moment it was rediscovered the sculpture was immensely popular, praised for its anatomical accuracy, and for its dynamic pose. As a result, many reproductions were made for collectors around the known world: we appear to be looking at one of them here.

The man on the left has grey hair, and wears glasses, signs of increased age, but also symbols of wisdom and maturity. Notice the position of his hands: the right holds the edge of the table at the front, while the left rests on the plinth of the statue between the legs. The man’s arms are therefore around the sculpture, the implication being that he is presenting it, in some way, to the other two. Given the extent of the shadows the precise direction of his gaze is not entirely clear, but to my eye he seems to be looking slightly to the left of the sculpture. One of the ideas about this painting is that, like the Air Pump and the Orrery, there is some kind of lesson or explanation going on – his action is, in some way, didactic: this older man is passing on his learning to the younger pair. If this is the case, then I would suggest that the niche behind him represents a form of ‘container’ – the knowledge contained in his head for example. The closed door behind the younger men could represent the knowledge about to be opened up for them, in the same way that the light can represent enlightenment.

The detail above also demonstrates how Wright’s compositions could be extremely rigorous. The older man’s head is tilted on a diagonal from top left to bottom right, and the man who we see more or less full-face – the man with the bright red lapels – has his head tilted the other way. As well as opposing one another, these angles parallel the diagonals of the Gladiator’s legs and body. Between the legs, the arms of the men to the left and right form a ‘V’ (only just visible here), creating a diamond of dark, negative space between the sculpture’s legs. The forward thrust of the form, with the stretched arm and bent knee, frames the man in red’s face, as well as creating a counterpoint with his lapels, which are not only angular, but also, thanks to the deep shadows, incredibly sculptural.

It is this man – with the red lapels – who holds the candle stick. The candle itself is visible, but the flame is hidden by his companion’s shoulder: in true Caravaggesque fashion, you do not see the naked flame. The third man – presumably a fellow student – is actually a self portrait, while the model for the man in the centre was Paul Perez Burdett, a friend of Wright’s, and the man who persuaded him to go to Liverpool. Wright – or the character he represents – holds a drawing of The Gladiator. It is sometimes said to be a print, but it is worthwhile remembering that prints reproduce imagery in reverse, whereas here we clearly see that the figure is in the same orientation. Having said that, at least one 18th century engraver made sure that he reversed the image on the plate so that the print accurately reproduced the sculpture as reaching forward with its left arm. However, I don’t get the feeling that a plate has been applied to this piece of paper – there is no sense of an impression, or of a blank border around the image: I’m sure it is a drawing. Of course, I could be wrong! The sculpture has been drawn from a different point of view from the one we see, although if we were to sit at the front left of the table – just to the right of the older man – we would get more-or-less this point of view, with the back of the head partially hidden by the shoulder.

The different viewpoints are important: points of view – and how you see things and show things – constitute one of the major subjects of this painting. As I’ve already suggested, the candle and the light it sheds are commonly seen as symbols of knowledge and learning – and hence of the Enlightenment, that great intellectual development of the 18th century. But how is the older man enlightening his students? What knowledge could he be imparting? Some sense of the importance of Ancient Greek sculpture, which only began to be appreciated (or even distinguished from Roman) in the 18th century, perhaps? Or the ways in which you can appreciate sculpture. Viewing it by artificial light – lamps or candles – was often advocated, as this creates shadows, thus emphasizing the sculptural form. The tutor might be thinking about the qualities for which one could or should evaluate a work of sculpture – for example accuracy, simplicity, boldness, balance, energy, and ‘purity’ (the mistake was made that the whiteness of the marble should be equated with an ideal, as people had not realised that Greek sculpture was originally highly coloured). However, this man may well not be looking as far back as Ancient Greece. He might have been inspired by the Renaissance, and the debate known as the Paragone –the comparison of one art form with another. In this case, there is a comparison between three forms, sculpture, painting and drawing: what are the relevant values of each, and which is superior? We see a direct comparison in the painting between the sculpture and the drawing – which helps us to see different views of the sculpture itself. This could be seen as one of the strengths of painting, as the painting shows us both. A weakness of drawing, perhaps, is that it only gives us one view, whereas, if we were to walk around the sculpture, we would see many different views. Given that the sculpture is this size, we might not need to walk round it though. It is possible that the tutor is not just presenting it, but also turning it round. Of course, he might actually be evaluating the standard of draftsmanship: the way I see it, he appears to be looking at the drawing, rather than the sculpture, and the two ‘students’ are, I think, looking at him (oddly the direction of a gaze is one of the aspects of painting that different people seem to read differently: there is another example I’ve had to confront when talking about the Air Pump – but we’ll come back to that in November).

Whatever the men are looking at now, were they to look at the sculpture they would all see it from a different point of view, and the limbs of The Gladiator would create different patterns in space for each of them. In this way the painting reminds us of the strengths of sculpture as an art form. However, the painting has advantages over that. Quite apart from our view of teh sculpture, we see each of the men from a different point of view – right profile, three-quarter profile and left profile, roughly speaking – and we can see these points of view without even having to move. Not only that, but the painting, unlike either the sculpture or the drawing, shows us the real colours of things. The intellectual skill required to show a three-dimensional object on a flat surface was also highly valued, and thus considered (by some) to be a sign of a painter’s superiority when compared to a sculptor. And of course painting can also allow us to see something that isn’t there – and that might include the very reproduction of The Gladiator that these persons are viewing. Let’s have another look at the original sculpture.

The tree trunk is clearly not just a convenient surface for Agasius to inscribe his name: it is there to support the mass of marble. Not only would the legs be too thin to support the weight of the torso, but the trunk helps to anchor and balance the forward thrust of the sculpture as a whole. It wasn’t necessary to include the tree trunk in the replica depicted by Joseph Wright, as it is not as large, and so – quite simply – not as massive: there would be little or no chance of the legs crumbling. However, the majority of reproductions of the sculpture were made in bronze.

This is an example from Houghton Hall, the Norfolk house built in the 1720s for Britain’s first Prime Minister, Robert Walpole. The bronze is more-or-less the same size as the original, and was made by Hubert le Sueur some time before 1745 for the Earl of Pembroke. Originally intended for his home, Wilton House, it wasn’t long before he gave it to Walpole. Although life size there is no tree trunk, as bronze has a far greater tensile strength than marble, and can easily support its own weight. However, the reproduction does have a sword (gladius in Latin, hence Gladiator) and a shield – reflecting the 17th century ‘restorations’. Smaller reproductions were also usually made in bronze, as they would be far easier to reproduce – you can cast multiple examples from a single mold. I suspect that Wright chose a marble version because it looks better in the candlelight, and stands out more from the dark background than a bronze would. It would also lend itself to a discussion of the virtues of the pure white marble, thus adding to the meaning of the painting. However, that doesn’t mean that Wright had actually seen an example like this, even if there are quite a few marble copies – but if he did, the version he saw is not known.

It seems unlikely that Wright ever visited Houghton Hall, but if he had he would have seen the sculpture in an ideal setting: it is displayed on a pedestal in the centre of the Grand Staircase. To appreciate the sculpture fully you just need to climb the stairs, and then descend. You would start behind the pedestal, looking up and from the far side. You would then turn left and climb the flight of stairs on the left of this photograph, and then turn left again to get the present view, before walking along the landing on the right. Climbing the next flights of stairs you would see the same side of the sculpture as before, but from above. Going from bottom to top and then top to bottom the stairs take you round the sculpture twice, giving you not only a 360° view around a vertical axis, but also views from below and above. Not only can see it all the way round, but also from top to bottom – every available viewpoint. What could be better? Should you ever find yourself at Houghton Hall do try this – but please, also look where you’re going. I wouldn’t want you to end up in a crumpled heap appreciating the decoration of the ceiling.

Richard hi, I’m having difficulty accessing your blog. I receive your weekly emails but can’t access the blog. Do you know if WordPress have changed anything.

kind regards Michael Jones

LikeLike

Hi Michael,

I’m not sure what the problem is, to be honest… the ‘weekly emails’ are effectively the blog. Earlier posts should be accessible via the website, and then the button you’ll see top left of the page:

…or, to cut out a step,

https://drrichardstemp.com/blog-3/

Hope that helps!

Richard

LikeLike

Thanks Richard for your reply. The more I tinker around with my lapt

LikeLike