Workshop of Goossen van der Weyden, The Flight into Egypt, about 1516, National Gallery, London.

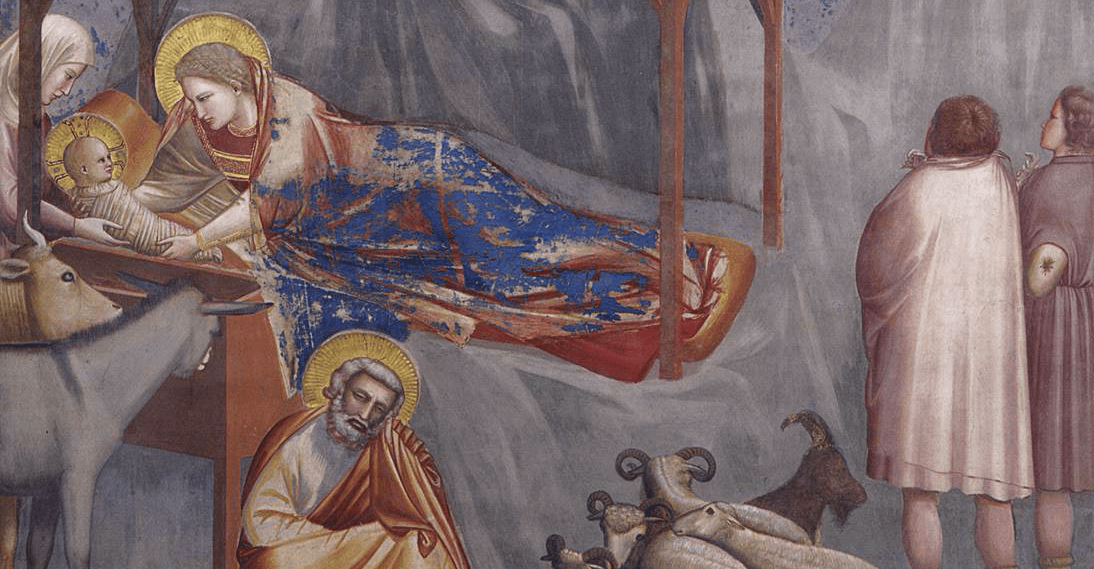

I am so sorry about yesterday. I was expecting it to happen at some point, but I didn’t know when. Basically other things just got in the way, and I was in no position to write – especially as I was doing the Cummings Commute, from work in London to lockdown in Durham. I’m sure this will happen again, but I’m going to carry on (as if yesterday didn’t happen), until I get to Picture Of The Day 100. After that, I will keep going as and when I can. I will probably write a few times a week, but we’ll see! Meanwhile, let’s get back to the art, and a third Flight into Egypt, following on from Picture Of The Day 85 and 87. During the former I said that the source for these images was biblical – Matthew 2:13-14 – but that there could also be additional outside sources. This painting from the National Gallery is a good example, as it includes two stories that were not in Juan de Pareja’s version – although there is no guardian angel, included by both Pareja and Giotto.

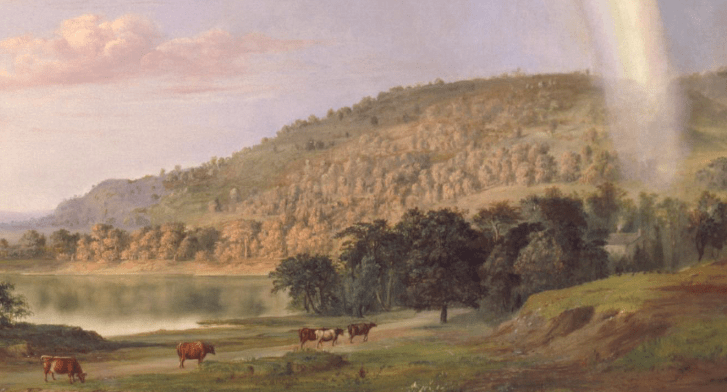

The focus of the painting is the Virgin Mary, feeding the Christ Child and sitting on a gloriously hirsute donkey. They are passing in front of a dark wood, travelling along a path which leads along a shallow diagonal to the bottom left-hand corner of the painting. Mary’s dark blue clothes stand out clearly from the grey of the donkey, and, together with the dark green of the trees, the blue helps to focus our attention on her face, which is pale and flawless, and on her breast. Mary has already played her part in our salvation by bearing Jesus, but continues to do so by nourishing him. His tiny head – the same size as the breast – and the white cloth in which he is wrapped (perhaps a precursor of the shroud) makes his image shine out from the darkness.

The donkey is placid and dutiful, it needs no leading. Although Joseph is a few steps ahead, and holds a rope tied around the donkey’s head as a halter, there is no tension – he is guiding, but not compelling. He holds the rope in his left hand, which is held behind his back – this means that we can see his hand, and can tell that he is in control. The loop of the rope also echoes the folds of his red robe, and the shape of the gourd, which has been hollowed out as a water flask – one of his most common attributes, or symbols. Others include a flowering rod, or staff, a reference to the story of the betrothal of the Virgin, but that is not included here (for the story, see POTD 31). In this painting he is a walking stick, another of his attributes, as is the bag slung over it. They have come to a sharp bend in the path, and Joseph is already round the corner. In between his feet and the donkey’s is a small water trough, with water flowing out to form a stream crossing the path. This is undoubtedly a reference to Jesus as the water of life, and to the idea of Baptism – the washing away of sin. The turn in the path is a clever compositional device – not only does it make the painting more interesting to look at, it also enhances the sense of movement and directs our attention to the two scenes which play out in the background.

Soldiers emerge from one of the gates of the city – Jerusalem – heading towards a small village – Bethlehem. One group is crossing the bridge which leads out of the city, while another has already made some headway. The latter group, closest to Joseph’s nose (on the picture surface, at least), has a leader on a white horse, others hold spears, and a few have flaming torches. At the point where the buildings emerge from behind the trees, flames are visible: they have set fire to the village. On the green a woman stands with her arms in the air, a soldier attacks another woman to the left, while on the right a third woman runs away from another soldier. This is the massacre of the Innocents: Herod’s soldiers have come to find Jesus and to kill him, and so as not to be outwitted, they kill all the children under the age of 2 (Matthew 2:16). Pareja included this story in the background of his painting, although it was far too small to be seen with any clarity, whereas Giotto dedicated an entire painting to it.

Closer to us is a ripe field of grain, unusual for January, you might think, particularly as we would appear to be in Northern Europe rather than the Holy Land. The crops are being harvested by a man with a scythe, who is addressed in a somewhat operatic fashion by a soldier, fully clad in 16th Century armour, who gestures towards the right of the picture. This story, which grew up during the middle ages, and is included in the background of more than one National Gallery painting, is written down in a text called La Vie de Nostre Benoit Sauveur Ihesuscrist – ‘The Life of Our Blessed Saviour Jesus Christ’ – which was written some time around 1400. One of the episodes it relates tells how, when the Holy Family were fleeing Bethlehem, they passed a man sowing his crops. Jesus (who was, remember, less than a month old) took a handful of the seeds and scattered them, whereupon they grew to head height. When one of Herod’s soldiers asked the farmer if he had seen a family passing by, he replied, ‘yes, when I was sowing seed’ – but as the crop was already fully grown, and ripe, the soldier calculated that it must have been some long time before, so it couldn’t have been the Holy Family.

On the far right of the painting, in a dead tree, is a monkey (in the dark at he top right of this detail). There are several references here! One is the old idea that ‘art is the ape of nature’ – although in this context the monkey is unlikely to be a comment about the nature of picture making. It is more likely to represent man at his most animalistic, his most uncivilised: a monkey is like a man but without the manners, and so could be a symbol of the sinners that Jesus has come to save, washing them clean with the water of life. And the dead tree? Quite possibly a reference to Ezekiel 17:24:

And all the trees of the field shall know that I the Lord… have made the dry tree to flourish…

This can be interpreted in more than one way – either as a symbol of Mary’s virginity (Mary is the ‘dry tree’ which ‘flourishes’ with Christ’s birth), or as a prophesy of the Crucifixion (the Cross is sometimes described as a tree, and Jesus as the fruit of the tree) – or, for that matter, both. Both is almost always possible when interpreting symbols! However, the main reason why I chose to talk about this painting this week, given that we have already seen two flights into Egypt, is the detail to the left of the dead tree.

A column rises from a hollow cubic base, and at the top stand two legs and a pair of buttocks. Tumbling down is a torso with an arm, and on the ground are a head, a hand, and a commander’s baton, a symbol of worldly authority. This illustrates another anecdote from La Vie de Nostre Benoit Sauveur Ihesuscrist, which tells us that, as Jesus entered into Egypt, the pagan idols all crumbled, and fell to the ground: the triumph of Christianity is acknowledged by the end of pagan statuary. At some point in history a statue was erected to someone who, given his staff of office, was some sort of figure of authority, but to God this was an idol, it represented someone unworthy of respect, and he has toppled it. Statues have always been toppled. It is part of the history of mankind.