Yoko Ono, FLY, 1996. Richmond, Virginia.

As I post this I’m on my way home, having talked to a group of Tate sponsors – a well-established firm of lawyers – about the exhibition Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind. I will repeat this talk for a potentially more discerning group (you) this Monday 27 June at 6pm. Having said that, they were great audience, and, from what they said, minds (and maybe even hearts) were opened. Much fascinating conversation ensued, albeit with the inevitable legal exactitude which requires that the precise meaning of each term be made clear. So, to practice my precision, I will focus today on just one word. Next week I will talk about Michelangelo (the first of at least three talks I will be giving about the Renaissance giant this year), and will introduce the British Museum’s beautiful and elegant exhibition Michelangelo: the last decades. The rest of June (on Mondays at least) will be given over to women – starting with a forgotten late-baroque master, Giulia Lama, and continuing with the British artists from 1520-1920 who can be seen at Tate Britain – more about them soon (it should be in the diary by Monday). But now for that word: FLY.

Those of you familiar with my posts will now be wondering what I can possibly say about this image. What I would usually do with a painting or sculpture is, quite simply, to look at it and write about what I see, exploring the full content of the image by picking out relevant details and considering each one in depth. But what details could I possibly select from this photograph? It is a billboard, somewhere in or around Richmond, Virginia, with a single word in bold capital letters – and a short word at that: FLY. What could there be to say? First of all, I would ask you to think to yourself, ‘What was the first thing I thought when I saw this word?’ What does it mean? And not only what does it mean generally, but what does it mean specifically to you, personally? And how many different meanings could the one word FLY possibly have? Well, quite a few, as it happens. First of all, is this a noun or a verb? Or for that matter, could it be an adjective? Well yes, it could. If you want many of the possibly uses of the word you could do worse than look at the entry on the Merriam-Webster Dictionary website.

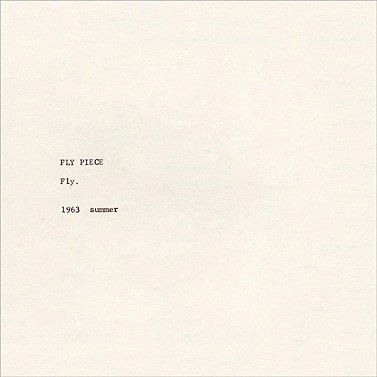

Of course, in terms of meaning, context is everything, and so to understand this billboard it would really help to remember that it is a work by Yoko Ono: it would be worthwhile using her output as the context. Her first use of the word, as far as I can see (but trust me, this is by no means an exhaustive survey) dates back to 1963. It is a work called FLY PIECE which was published the following year (1964) in her book Grapefruit. Here is the work, together with the cover of the book.

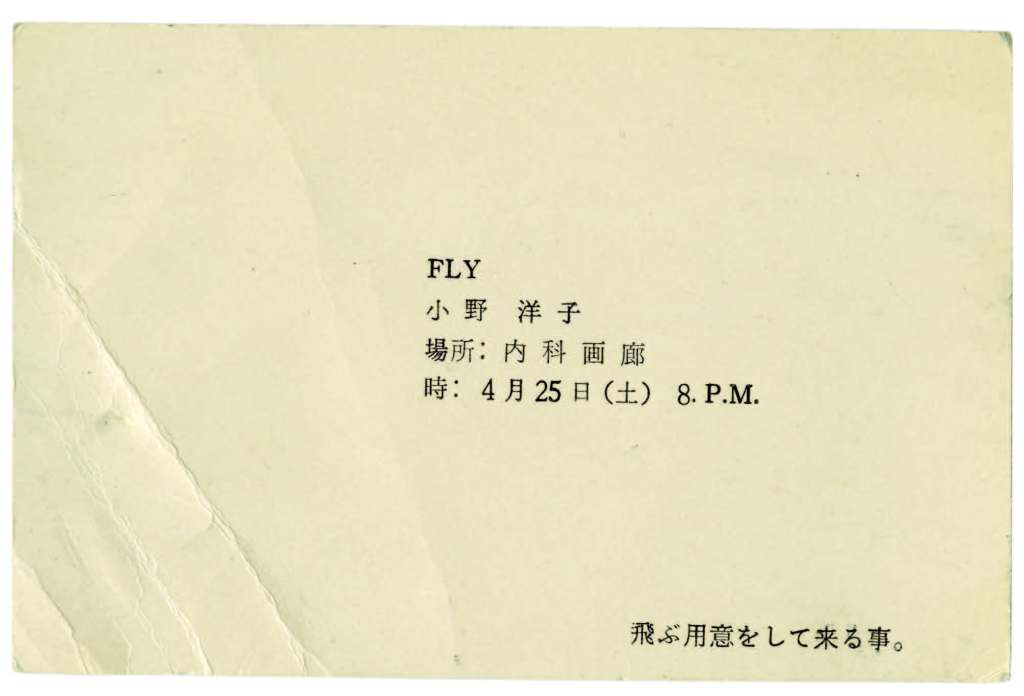

Again, it is a work of apparently utter simplicity – the title (FLY PIECE), the word ‘Fly.’ (with a full stop) and the date, ‘1963 summer’. Grapefruit included over 200 of what are known as her ‘instruction pieces’, which are suggestions for works of art which she, or someone else (including you), might make. Ono was at the very forefront of conceptual art (which I will talk about more fully on Monday), and these instructions include suggestions for paintings and actions which may or may not be made or performed – but whether they are or not, the ideas – the concepts – now exist. The work is out there in the world, even if it is only in peoples’ minds and imaginations. As far as this particular work is concerned, though, if this is an ‘instruction’, that would imply that ‘Fly’ is a verb, something to do. We are being invited to fly. You can imagine for yourselves how you might achieve that. One of the suggested possibilities came the year after the original concept, the year in which it was published. Here is the announcement of an event which took place in Japan on 25 April 1964.

In between the Japanese symbols you may be able to pick out the numbers ‘4’ and ‘25’ – 25 April – and the time, ‘8. P.M.’ The title of the event is clearly printed in English: ‘FLY’. The only photograph I can find of this Japanese performance is almost illegible, but in England it was repeated more than once – both at the Jeanetta Cochrane Theatre in London, and then at Bluecoat in Liverpool, in 1967. This is a photograph from the latter.

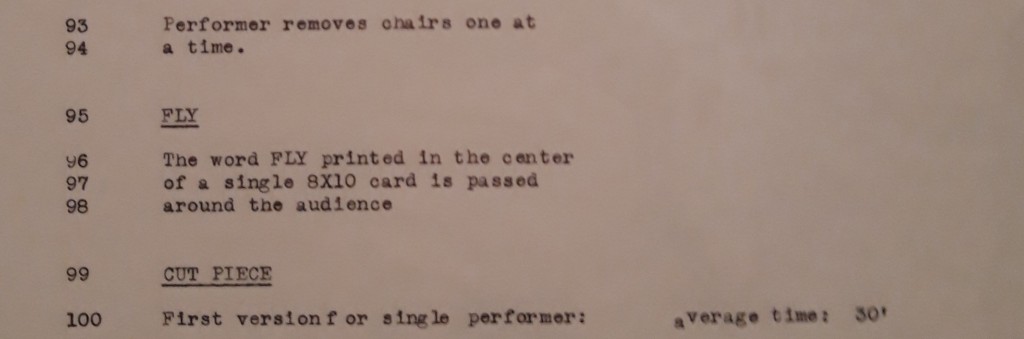

Members of the audience were invited to come up onto the stage, climb as far up the ladders as they liked, and then leap off – to experience, however briefly, the freedom of flight. Yoko Ono’s work has always been open – open to interpretation, open to collaboration – and incomplete. It is waiting to be completed by the active participation of the audience, of the viewer, of you. A few months after the original performance in Japan, FLY PIECE was followed by the Yoko Ono Farewell Concert. August 1964 marked the end of a two-year extended visit to Japan (the country of her birth), and this performance was, as the title suggested, her Farewell before she headed back to New York. The Concert included one of her most important works, CUT PIECE. The script – or score – of the concert was published two years later, in 1966, and, as you can see, CUT PIECE was preceded by another version of FLY which is worthwhile considering.

In this case it was a piece of card handed around the audience which bore the same instruction – the same invitation – to FLY. To let yourself go, I suppose, to free yourself from whatever is holding you back. Thirty-two years later, the billboard must have had the same intention. You could even argue that it is the same work, with a billboard better able to communicate to a wide audience than a single, relatively small card. However, the tone shifts – along with the meaning of the word – in 1968. In that year she published Thirteen Film Scores by Yoko Ono, London ’68, which included the score for Fly (Film No. 13).

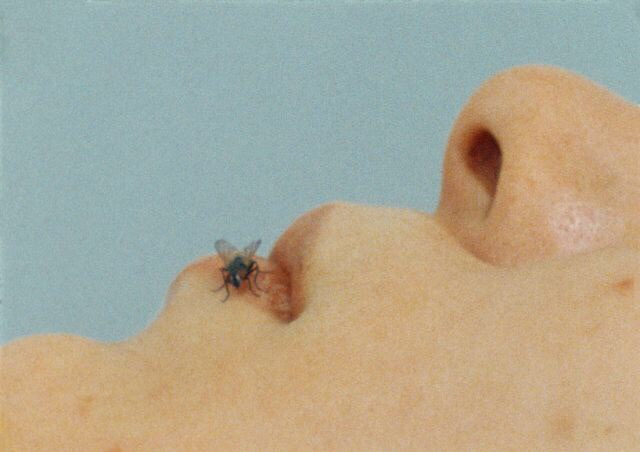

The words are quite simple, although you have to question how, as a filmmaker, you could make a fly follow instructions. But why publish a score (I’ll talk about her use of the term on Monday) rather than just making the film? Well, Ono had prefaced an earlier collection of film scores – published as part of Grapefruit – with the following explanation – or suggestion: ‘These scores were printed and made available to whoever was interested at the time or thereafter in making their own version of the films, since these films, by their nature, became a reality only when they were repeated and realized by other film-makers.’ As it happens Fly (Film No. 13) was made a few years later (1970-71) by Yoko Ono herself, in collaboration with John Lennon. They both directed, with Lennon also acting as cameraman. He also played guitar on the soundtrack (which was released later in 1971 as one of the tracks on the album, Fly). The film lasts 25 minutes, and is being continuously screened as part of Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind at Tate Modern. Here is a still as a taster.

Suddenly the concept of flying free becomes less… acceptable, maybe even gross, particularly given that the score was not followed to the letter. For one thing, there were a multitude of flies, apparently credited as ‘supplied by New York city’, crawling over the supine, passive, and naked body of actor Virginia Lust. This might, perhaps, come as something of a surprise. However, it would be worthwhile remembering that flies have featured in art for centuries. Here, for example, are two paintings from the National Gallery, together with relevant details. The first is a Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family (about 1470) by an unknown Swabian artist, the second, Carlo Crivelli’s St Catherine of Alexandria (probably about 1491-4)) – a panel from one of the pilasters of a dismembered altarpiece.

In both paintings the fly could be seen as a memento mori – a reminder of death – and so also of the transience of life. This is not only because flies themselves do not live so terribly long, but also because they are often associated with dead meat. With St Catherine this would serve as a reminder to be good Christians, so that after death – which is inevitable – the viewer would rejoice in an eternity in paradise. The equivalent meaning could also be true for the unknown member of the Hofer family (who was presumably supposed to be a good Christian), but it could also be a reminder that, although the subject of the portrait is long gone, her memory lives on. This would make the painting an embodiment of the popular Renaissance motto ars longa vita brevis – which can be translated as ‘life is short, but art will endure’. The suggestion that the fly might be related to artistic rather than moral or religious values gains support if you stop and wonder where the fly is actually standing. Has it really alighted on the woman’s headdress, for example, or on the architectural surround of St Catherine’s niche? Or, in each case, is it actually supposed to be standing on the surface of the painting itself? The idea that the artists are trying to suggest that a real fly has landed on top of their paintings is perhaps more relevant for the Crivelli, where the fly is apparently larger than St Catherine’s thumb. Either it is out of proportion, or it is not part of the same visual world. In both cases, though, the fly can be seen as a form of trompe l’oeil.

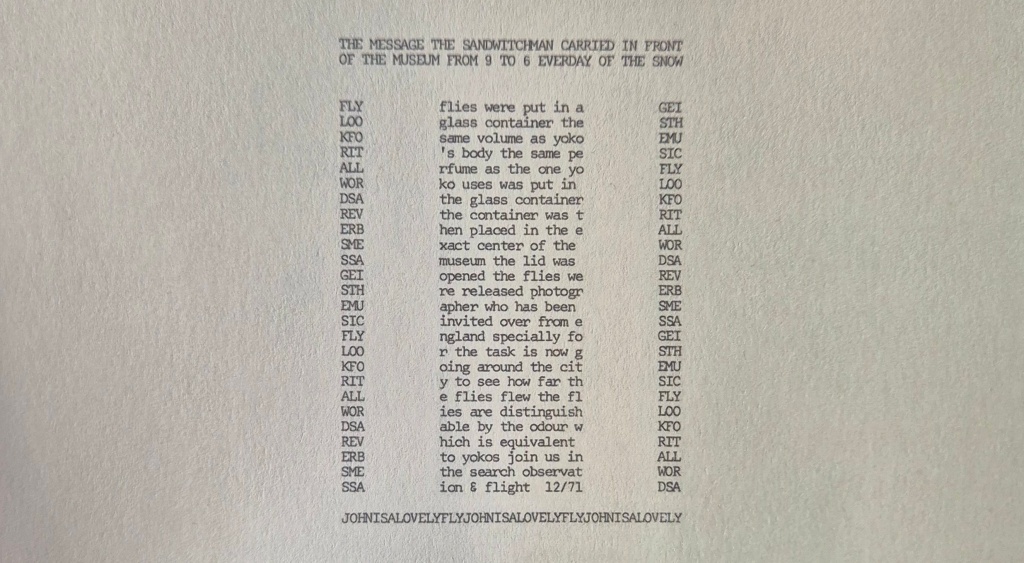

I’m not trying to suggest that there was any similar trickery in Ono and Lennon’s film: the flies were definitely there. I’m just pointing out that flies have a long history in art, and so the film does have a connection with the Western European tradition. The sense of transience is undoubtedly important. Earlier films by Yoko Ono slowed down simple actions to make us aware of the passage of time, and therefore of the transience of human existence. The stillness of the model in Fly also gives us a sense that time has slowed down for her – even if it hasn’t for the ever-active flies. The wording of the original score is also important, though: the fly was supposed to ‘fly out the window’. It finds its freedom. As I’ve said, Lennon played guitar on the film’s soundtrack. However, the vocals were supplied by Ono. While doing this, she imagined herself as the fly – indeed, she has suggested that both human and insect were effectively self portraits. In Cut Piece she sat passively while allowing members of the audience (mainly male, at the time) to take what they wanted, cutting away sections of her clothing with a pair of scissors left in front of her. This, together with the passivity of the female form in Fly, can be read as a critique of the role that ‘society’ (for which read, ‘mainly men’) required of women. So should we read the flies as the men, crawling all over her? Inevitably, it’s not as simple as that, as the fly eventually soars free – or at least it is supposed to, according to the score. Also, as it happens, she was not entirely against flies. The following is a page from the self-published exhibition catalogue for her irreverently entitled Museum of Modern [F]art – a solo show which (surprise, surprise) was not staged at the (almost) eponymous New York institution in 1971 – even if actions, and photographs, for the exhibition do appear to have taken place there.

To make things easier, here is a transcription of the central section of the script:

flies were put in a glass container the same volume as yoko’s body the same perfume as the one yoko uses was put in the glass container the container was then placed in the exact center of the museum the lid was opened the flies were released photographer who has been invited over from england specially for the task is now going around the city to see how far the flies flew the flies are distinguishable by the odour which is equivalent to yokos join us in the search observation & flight 12/71

Whether or not this actually happened is irrelevant: she has created the situation, told you the story, and now it exists in your mind, whether it happened or not. The words in the left and right columns are also important. In capital letters, but without gaps, is the repeated phrase,

FLY LOOK FOR IT ALL WORDS ARE VERBS MESSAGE IS THE MUSIC

So – we are being invited to look for the fly. However, if ‘all words are verbs’, we are also being invited to fly and look for it. We are being provoked into action, into ‘doing’ – and so we are encouraged to take flight, to be free. Across the bottom of the invitation is the repeated assertion,

JOHN IS A LOVELY FLY JOHN IS A LOVELY FLY JOHN IS A LOVELY FLY

It seems unlikely that she associated her husband with carrion. However, he was undoubtedly a free spirit – just like a fly.

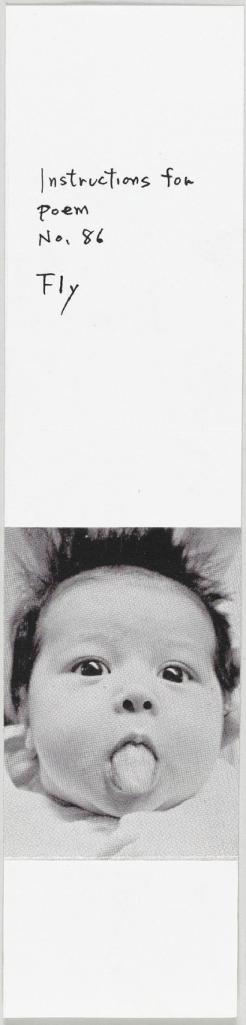

I have one last image for you, which not only adds to our understanding of the billboard (I hope), but also, like the title of the above exhibition, reminds us that Yoko Ono does have a sense of humour. It is her Poem No. 86 – which was published with the announcement of the birth of her first child, back in 1963. The Instructions for Poem No. 86 are quite simple. What does she wish for her child? A long life, happiness, and success, presumably. But how does she put that? How do you encourage people to reach their full potential, to achieve the most, and to reach the heights? If you are being optimistic (and Ono is nothing if not optimistic) what do you suggest they do? Here’s wishing you may do the same.