Laura Knight, Laura Knight with model, Ella Louise Naper (‘Self Portrait’), 1913. National Portrait Gallery, London.

Happy New Year! And as this is the first blog of the year, let us start with a woman who could count several ‘firsts’ to her name: Laura Knight. Or, if you prefer, Dame Laura Knight: in 1929 she was the first female artist to receive this honour. Seven years later, she was also the first woman to be elected to full membership of the Royal Academy, and in in 1965 she was the first woman to have a solo exhibition there. I will be talking about her more this Monday, 10 January, as an introduction to the MK Gallery’s exhibition Laura Knight: A Panoramic View. Further talks in January will include Late Constable, some Masterpieces from Buckingham Palace and a pair of Pre-Raphaelite Sisters of Uncommon Power. As ever, the details of all of these – and other things – are on the diary page. I am also hoping to deliver some in-person visits to London museums and galleries, focussing on the National Gallery where I am most at home, but I think I’ll wait for Covid numbers to calm down a bit before I start, so… maybe in February? Watch this space! But whatever follows, let’s look at a rather brilliant painting.

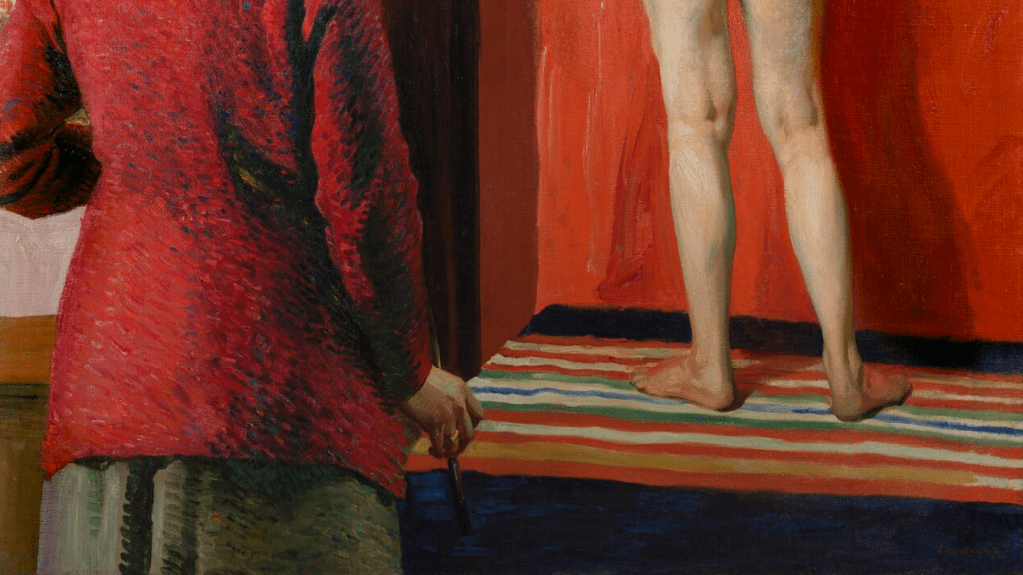

It’s a remarkably original choice for any artist – a self portrait seen from behind: she is focussing on what she does, not what she looks like. Knight appears sensibly dressed, with a mid-length red jacket over a grey skirt, and what I would interpret as a striped foulard around her neck (although, as you probably realise, I am not an expert on women’s dress). As it happens, it’s not a jacket, per se, but a favourite cardigan, which she called ‘The Cornish Scarlet’. She had bought it at a jumble sale in Penzance for half a crown (or 2/6, or 12.5p, depending on your age), and it appears in a number of her paintings. Nowadays it would be classed as ‘vintage’ and cost a whole lot more. She also wears a black hat with a colourful ribbon almost hidden by the upturned brim: all respectable women should wear a hat when in public. Her hair appears to have been plaited and pinned up. If she hadn’t turned her head to the right, we wouldn’t be able to tell who she was – and it is not clear why she has turned so far: certainly not to look at the model, as she looks past her, to something out of the frame. She is holding a paint brush in her right hand, and, from the bend of her left elbow, we can imagine that she is holding a palette in her left. The model, who is completely naked, stands with her back to us on a striped rug, which is itself on a raised platform. While her feet are more or less parallel to the picture plane, she is turned to the left, allowing us a partial view of one breast. She raises her arms around her head, with her right and left hands resting on her hair and right arm respectively. Behind her is a red screen – maybe a folding screen, although the right-angled section to the left has a trim not seen in the plain vermillion area behind her – this could even be a brighter cloth hanging over the screen, but the construction is not entirely clear. In front of it, though, to the left, and behind the image of the artist, is the canvas that Knight is currently working on. Having seen the model herself, here we see her painted image, and, to the left of her, the part of the red screen that the artist has completed so far.

The inflection of Knight’s right wrist means that her hand is held away from her hip, so that she will not get paint on her skirt. It also serves to draw attention to this hand, and to the gold ring on the fourth finger. It looks like a wedding band, even if it is on the right hand (I don’t think she was looking in a mirror to see what her own back looked like: the clothing itself does not reflect her appearance, and she may well have got someone else, possibly even the same model, to model for the back – so I don’t think that this is her left hand as seen in a mirror). She was born Laura Johnson in 1877, taking her husband’s name when she married artist Harold Knight in 1903, at the age of 26. They were both born in Nottingham, and met at the Nottingham School of Art, where Laura’s mother taught.

In some of her early works she experimented with the pointilliste technique of George Seurat, and she continued to return to it when it suited her – as it does here in the separately coloured brushstrokes which define ‘The Cornish Scarlet’. In this case, the brushstrokes are perhaps closer to the Impressionist tache (meaning blot, patch or stain) – a short, broad mark which emphasizes the making of the image. The brushstrokes do not allow us to confuse the painting of the cardigan for the thing itself, it is undoubtedly a painting. What you are looking at, the brushstrokes say, is the work of an artist. How appropriate that she uses this technique as part of her own image, given that she is the person who made it.

If the depiction of herself – or at least of her clothing – focusses on colour, the depiction of the model is all about form. Look how the precise tonal shifts tell us the exact structure of the feet, the slight lift of the right heel from the rug, the width of the Achilles tendon, and the structures of the muscles and the backs of the knees.

Looking at this detail I am more convinced that there is a cloth hanging over the screen – the vermillion appears to wrap around the dark frame. And the painting of this cloth is entirely different to that of the cardigan – extremely ‘painterly’, with long, broad, flowing brushstrokes painted wet-on-wet and blending in with each other. Although not part of the image that she has painted of herself, the use of a different ‘style’ of painting is surely another way in which she is inviting us to enjoy her skills as an artist, demonstrating as it does her ability to choose the brushstroke according to the nature of the material she is representing: here the vermillion cloth is broad, and flows downwards, just like the paint. The subtle but precise modulation of flesh tones continues, defining the curve of the spine and flexion of the muscles, as well as delineating the model’s long, slim fingers. Compared with the impressionistic image seen in Knight’s unfinished painting of the model, this might start to appear like photorealism – but the brushstrokes never let us forget that it is a painting. The canvas she is working on is still clearly unfinished, though. She may have started to paint the model’s shadow on the screen, but not the lit area: the white background remains, and is precisely what allows Knight’s bold profile to stand out so clearly.

When first exhibited in 1913, at the Passmore Edwards Art Gallery in Newlyn, Cornwall (where the Knights were then living), this self portrait – then called The Model – was well received. But later it was apparently turned down by the Royal Academy for their Summer Exhibition, and instead was seen in London at the Grosvenor Gallery, where reviews were mixed, to say the least. The Telegraph Critic, Claude Phillips, called it ‘harmless’ and ‘dull’ (which it is not!) – but he seems to have been in two minds, as he also called it ‘vulgar’, saying that it ‘repels’. As a work which, he had decided, was ‘obviously an exercise’, he thought it ‘might quite appropriately have stayed in the artist’s studio’. So what was his problem with it?

I think that if we focus on this central section we might get a good idea. One of the first things to remember was that women had little or no access to life drawing classes. At Nottingham, the men and women (or girls – Knight studied there for around six years from the age of 13) had been segregated, and the women did not draw from the nude. The model in this painting is Laura’s friend, and fellow artist in Newlyn, Ella Louise Naper. So for one thing, this is a bold statement declaring that women should receive the same education as men. However, the way it is painted also creates some surprising juxtapositions. The light comes from the left – you can see Naper’s shadow on the screen to her right – and, given that Knight turns to the right, her profile is entirely in shadow. However, it still stands out clearly thanks to the brightly illuminated canvas. The negative space created by the artist’s profile – the brilliant white patch of canvas – is similar in form to the equivalent area in red around the model’s left side, with a startling echo from Knight’s nose to Naper’s breast. And, as Naper is standing on a platform, her brightly-lit buttocks are more or less on a level with Knight’s shadowy face, surely enough to make any self-respecting (male) critic blush.

As a whole, the contrast between the two women is intriguing. One clothed, the other naked; one has both arms down, the other up; the artist on the left is turned to the right, the model on the right is turned to the left. Their poses echo each other, inverting only the arms, with Naper’s right arm hiding her profile. Laura Knight, despite the shadow on her face, is the one we can identify, but the various echoes and inversions could lead us to think about substituting one figure for another, reminding us, perhaps, that the artist herself could easily look like this if she weren’t wearing clothes. I suspect it is this that made men uneasy. It was one thing for them to paint naked women – they could tell the difference between artist and subject, but in this painting, the difference is not so clear. That, and the fact that Knight’s acknowledged skill was clearly a threat to their supremacy, of course.

One last question: what painting is Knight actually working on? We know that it is not finished, but we only see part of it. Nevertheless, what we do see is entirely consistent with the idea that the work she is painting is the finished self portrait itself, if we assume that we only see around 40% of it – the section which includes the vermillion cloth. Laura Knight herself is taking a break from painting herself painting herself painting a model – her painted image in this painted image is beyond the frame. Having said that, I do have a sneaking suspicion that she would finish the red screen first.

This complexly-conceived portrait is not in the exhibition in Milton Keynes, but there are many more remarkable paintings which are: do try and get to see them in person! But if you can’t, I will be talking about many of them on Monday. One of them – one of her masterpieces, I think – is Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-ring. As Zoom is not very good with videos I won’t be able to show you a wonderful newsreel clip from 1943, so click on the link in blue if you want to do some homework! If nothing else, it’s worth watching to see Knight being handed a cigarette by the presenter, and both of them lighting up in the Summer Exhibition itself. Not to mention, of course, how remarkably accurate her portrait of Loftus is. But more about that on Monday – I do hope you can join me!

Loved this. Perhaps, Laura was turning to look at Sir Alfred Munnings? Perhaps, some views about her relationship with him might be worth mentioning. I can’t see why she adored Munnings so much myself! I love the Newlyn Museum. Always worth a visit on the way to the Scillies. I am so glad you are doing a blog on Laura Knight. Definitely one of my favourite artists. Looking forward to your talk on Monday. Margaret Rice-Oxley

Get Outlook for iOS ________________________________

LikeLike

I still haven’t found much about their relationship, apart from him being a friend of both Knights… something for further research, maybe.

LikeLike

Thanks, Margaret – sadly I don’t know Newlyn, but it’s on the list!

LikeLike

Thank you for lighting up paintings for all of us.

LikeLike

My pleasure – thank you – and I hope you’re well!

LikeLike

How curious to see Laura Knight greet her model Ruby with a kiss on the lips. Was this the usual way for a female painter to greet her subject? And you’re right as always Richard, she paints an extraordinary likeness.

LikeLike

It’s not a field I’ve studied, I’m afraid…!

LikeLike

Very much looking forward to your lecture this evening Richard

I thought Ruby Loftus Screwing à Breech-ring reminded of the Russian paintings after the Revolution, portraying women stepping into traditionally male jobs in industry.

As for the wedding band, it is traditionally worn on the right hand by Eastern Orthodox believers, although I don’t think it was Laura Knight’s case!

LikeLike

Yes – very much like Socialist Realism – and Nazi propaganda too – and yes – various societies put the ring on the left hand. But not people from Nottingham, as far as I’m aware!

LikeLike