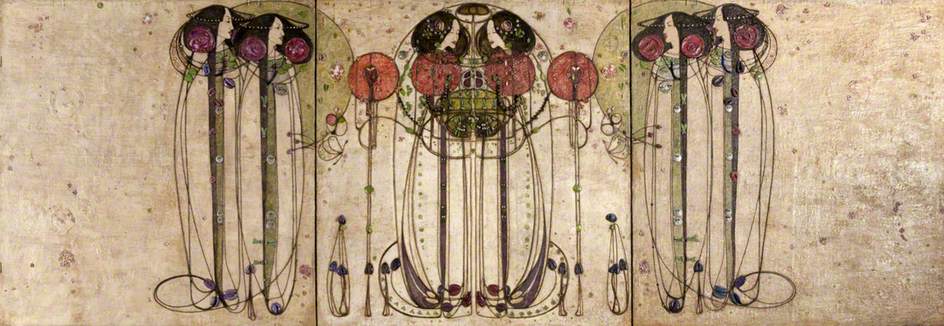

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, The May Queen, 1900. Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

My Elemental August is drawing to a close: thank you to all of you who attended the talks. I will miss that particular group of women with their resonances of time and place, training and travel, but it’s time to move on to what is proving to be a somewhat Scottish Summer. First up, this Monday, 4 September (and I will try to get the month right from now on) will be Two of The Four – looking at husband and wife team Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald, while also including the other two members of The Four, Margaret’s younger sister Frances, and her husband, James Herbert MacNair. The following week we will look at Whistler – and his Wife, Beatrix Birnie Philip, whose works, like those of The Four, are particularly well represented in the collections of the University of Glasgow (a small part of that talk will explain how this came about). To finish off the month, after a week in Glasgow itself, I will introduce a wonderfully rich exhibition which you can see in Edinburgh until January, Scottish Women Artists, a collaboration between the Fleming Collection and Dovecot Studios. As ever, keep checking the diary for anything new! Today, though, I want to look at one of the masterpieces of Margaret Macdonald.

The May Queen is a frieze made up of three almost square panels, painted on thick-weave hessian with gesso (effectively plaster), inlaid with twine and thread, glass beads, mother of pearl, and tin plate and painted in oils. The technique belongs to the world of the decorative arts, and indeed, this was made as part of the decoration of a very specific interior. However, when considering the art of Margaret Macdonald, or for that matter that of the Glasgow school around the end of the 19th century, and even more generally, trends in modern art at that time, it is important to remember that genres were opening out, and any technique or medium should really be seen as equivalent – and as important – as the Old Masters’ favourite, ‘oil on canvas’: you cannot consider the art of The Four without looking at their entire output.

The May Queen of the title is centrally placed, and flanked (framed, even) by four attendant maidens, symmetrically arranged with two on either side. They hold up garlands which surround the central figure and draw the entire group together.

Highly stylised, the Queen stands upright wearing a full dress which disguises her bodily form, falling steeply from the neck and reaching full width at about knee-level, where it curves in to a rounded base, hiding her feet, as if her body were made of a giant bud, or drop of water. She has dark, centrally parted hair, full on either side of her face, which then falls in long bunches of gradually diminishing width to a level just below her waist, where the two bunches join. This conjunction, and its positioning, may be intended to emphasize her sexuality. All of the preceding references to her anatomy are conjectural, though. There is actually no convincing evidence as to the nature – or position – of her body. The fastening of her clothing forms a vertical seam which runs the full length of the figure, not unlike the wing case of an insect. Overall there is the possibility of opening – of taking flight, if an insect, or of blossoming, if a bud. Inherent in this is a sense of the fertility of May, the promise of future growth, and of life.

She stands in front of a tree with a rounded canopy of leaves acting like an oversized green halo, with large pink forms of undefinable nature (but see below) framing her head, as does a series of symmetrically arranged, decorative, geometric lines. These have echoes of insects’ eyes, angular limbs, and potentially, even, a butterfly. Precisely what these elements represent is not clear, though, and indeed, one of the delights – and frustrations – of discussing the work of Margaret Macdonald and the other members of The Four is that they used a personal vocabulary of apparently secret symbolic forms which have never been fully explained. Aside from the bulging, fecund forms of the May Queen herself, the composition is defined by an insistent arrangement of horizontal and vertical elements. However, there is no danger of these looking mechanistic, as they curve, flow and flex, rather than maintaining a rigid structure. Three sets of unevenly horizontal lines scan the panel from top to bottom. A pair at the top define the Queen’s full height. At the level of her shoulders (does she actually have shoulders?) are the garlands held by the maidens on either side, and the ‘ground’ on which she stands is defined by three more lines, the upper one curving down under her feet (if she actually has feet).

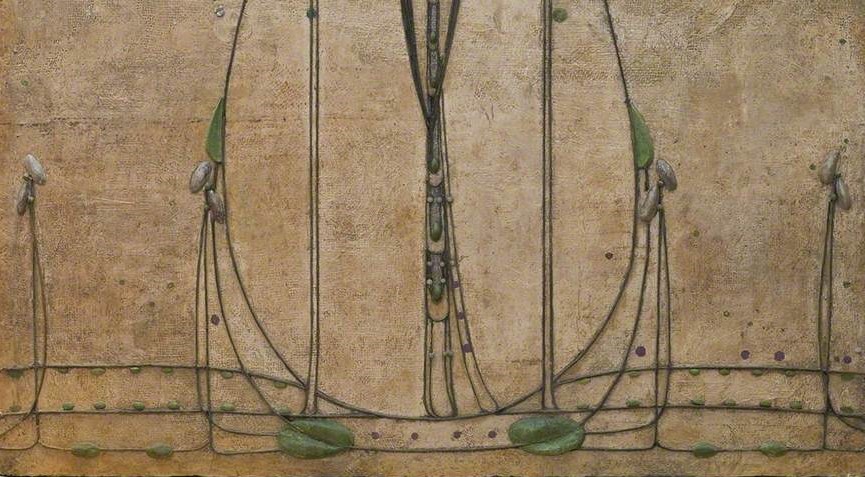

If we look at the bottom section of this central panel we can see how sparse the imagery is overall – effectively a drawing made from coloured thread against the textured, buff-coloured hessian. There is no indication when looking at this detail on its own that we are looking at a human form, although there are signs of life. Along the bottom are patches of green from which the lines appear to grow. On either side of the central axis these patches are at their largest, like bulbs, or corms, from which a stem, or trunk, grows vertically. On either side there other plants which grow to the height of he broadest width of the May Queen’s skirts, each with one or two mother-of-pearl petals and sometimes a green leaf.

The focus of interest, though, is at the top centre, around the shoulders and head of the Queen. Flowers – roses, presumably – are set in her hair, and are scattered across the tree. The broad, pink, fruit-like forms are covered in other blossoms. The linear framing elements are at their densest and most complex, surrounding – and revealing – the simple, stylised, apparently innocent face, which has pale pink flesh and deeper pink, blossom-toned lips. It is entirely formal, frontally, even hieratically placed, implying that this is a figure of great importance: the Virgin Mary of medieval art is often presented in a similar way. The garlands held by the maidens are painted purple behind her, and purple and cream in front, and are strung with purple and pink blooms. The May Queen wears a pale lavender cape, reminiscent of insects’ wings, decorated around the hem with leaf- or petal-like pendants. The colour is almost all contained within the bounds of the garlands and the leaves of the tree, and the mass of lines makes it look as if she is trapped within a giant game of cat’s cradle. The increased intensity of colour and line here are what really create the May Queen’s status. At the level of the leaf-like forms the stems growing up from the central corms branch, continue their upwards growth, and become the pink shapes flanking the Queen – rose bushes, it would seem. However, some of the stems break off horizontally towards her head, where they form part of her elaborate coiffure: what initially appeared to be growing up now appears to be flowing down. She is part of the natural world, an emanation of May itself, the spirit of spring growth.

The attendant maidens are entirely symmetrically placed, although not rigidly so, and show considerable influence from the art of Japan, notably in the broad, flat areas of colour and bold outlines. Each pair shares a single green tree and paired rose bushes, if indeed that is what they are, and hold their garlands with a stilted, formalised gesture implying a dance or ritual. They have similar faces and hair to the Queen, but seen side-on do not have the same imposing demeanour. Their parted hair falls in bunches all the way to the ground, and doubles as the hem of their robes.

When looking at the top section of the left-hand panel (the same would be true on the right) two things become more evident. The first is the amount of space that Margaret Macdonald has given them: they occupy little more than the right half of the panel. The negative space to the left adds to the atmosphere by isolating the figures within a world that is clearly worthy of attention, and helps to create a sense of great calm. Also clearer here is the branching of the stems – especially that on the left, which would appear to confirm the identification of the pink forms as richly blossoming rose bushes: individual flowers are blooming along the subordinate stems. As in the central panel the vertical stems suddenly grow horizontally, even forming strict right angles. However close we are to nature, this is a formal garden, with espaliered trees and bushes.

The lower section of the right panel – symmetrical, of course, to that on the left – shows how the growing stems frame the central motif, and create the geometric, rectilinear structure of the composition as a whole. The closure at the bottom right corner is made up of the curving hem of the right-hand maiden’s robe, and a final plant, blooming with tin petals, at exactly the point where its stem becomes a tangent of the broad curve of the falling robe.

The frieze was created as part of the decoration of the White Room in the Ingram Street establishment of the doyenne of Glasgow tea rooms, Miss Kate Cranston. Charles Rennie Mackintosh was commissioned to design the room as a whole – including its furniture and decorations – but the finished product was very much a collaboration. Margaret Macdonald’s The May Queen was paired with an equivalent frieze by Mackintosh, The Wassail. For years I have been unable to distinguish the two stylistically, but writing the above description of Margaret’s work has opened my eyes and helped me to find some difference.

Aside from the obvious similarities (the three panels, with identical materials, comparable background trees and differently disposed, but nevertheless equivalent rose bushes) and the most evident difference (there are two central characters rather than just one), there are also ways to distinguish the two works stylistically. For Mackintosh the outlines of the figures are far freer, looping energetically around the maidens, as if he were doodling in space. There is no ‘ground’ for them to stand on, or to tie them together, nor any espalier branches containing them at the top. This makes their bodies even more immaterial than in The May Queen. However, the heads are positioned more subtly, and more specifically. Whereas for Macdonald the heads of each pair of maidens are almost exactly the same – at the same height and turned at the same angle – Mackintosh places the heads of the outer maidens higher. This creates a sense of perspective: the inner maidens are further away. The heads are also angled differently. The outer maidens are in strict profile, whereas their inner companions twist their heads towards us at the neck, and lean the top back towards the inner shoulder: they are more naturalistically positioned, and more three-dimensionally conceived. This contradicts the entirely immaterial nature of their bodies, creating a magical, almost hallucinatory effect.

Before the two friezes were installed in their intended location, they were exhibited publicly – but not in Glasgow. The Four were invited to participate in the 8th Secession Exhibition in Vienna, held between 3 November and 27 December 1900. In 1899, the year before, Frances Macdonald had married James Herbert McNair, and in the year of the exhibition itself Margaret Macdonald followed her sister up the aisle and became Mrs Mackintosh. Although all Four contributed works to the exhibition, it was the Mackintoshes who travelled to Vienna to install the material: some of the display can be seen in the photograph above. As a result, it seems, it was Charles and Margaret who received all the adulation, with Macdonald was the overall ‘star’. Glasgow was already a noted presence on the international art scene, thanks to the work of the Boys – now known as the Glasgow Boys – whose paintings were included in various exhibitions across Europe (including Vienna) from 1890 on. The success of The Four in Vienna in 1900 confirmed Glasgow’s status on the world scene. The fact that these artists did not just paint, but also designed furniture, interior decoration, and even buildings (Mackintosh and MacNair were both architects) was an ideal match to the ethos of the Viennese Secession, with its firm belief in the Gesamtkunstwerk – all the arts working together to form a coherent whole. Within a couple of years the Wiener Werkstatte (‘the Viennese Workshop’) was founded, a direct equivalent of the British Arts and Crafts movement, and explicitly inspired by The Four, with founders Josef Hoffman and Koloman Moser asking Mackintosh for advice. Even the first President of the Secession, Gustav Klimt, was impressed, not to mention influenced. In 1902, at the 14th Secession exhibition, he created the Beethoven Frieze – this is just one section:

Unlike the Macdonald/Mackintosh panels, this was a mural, painted onto the wall itself. This means that, like the panels, it painted on plaster. It also included three dimensional elements, gilding, and inserts: glass, as used by Macdonald, but also unexpected, ‘cheap’ materials, like curtain rings. The frieze was only supposed to last the duration of the exhibition: it’s a miracle that it has survived until now. It was explicitly, and undeniably an adoption of the techniques for which Margaret Macdonald was celebrated. It also has an equivalent use of negative space, with most of the frieze effectively ‘unpainted’ (this detail includes one of the densest areas of imagery). There are even ‘Glasgow roses’ growing on a bush surrounding the kissing couple here, with stems branching in an almost identical way to those in The May Queen.

The Four were far more important for the development of art in continental Europe than in Britain, and they were more widely celebrated away from home, however central they were to the art of Glasgow at the time. The influence on the work of Gustav Klimt is just one demonstration of this. However, precisely who was the major innovator of the group is still open to debate. If you want a better idea, I can recommend Roger Billcliffe’s Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Art of The Four. As well as being a lecturer at Glasgow University, Billcliffe was also Assistant Keeper of the University Art Collection before moving on to become the Keeper of Fine Art at Glasgow Art Gallery – and so has first-hand experience of two of the best collections of their work. His book takes a careful, even forensic look at the evidence to hand – the paintings, drawings, prints and other materials – and has very specific, and well-reasoned opinions about the artists, which are not necessarily what you might expect. They are certainly are not what I had always thought. But if you want to know more about that – then sign up for the talk on Monday! I will try to make it as balanced as possible, and will also try to explain why it is hard to be more balanced. Then I’ll leave it up to you to decide what you think.