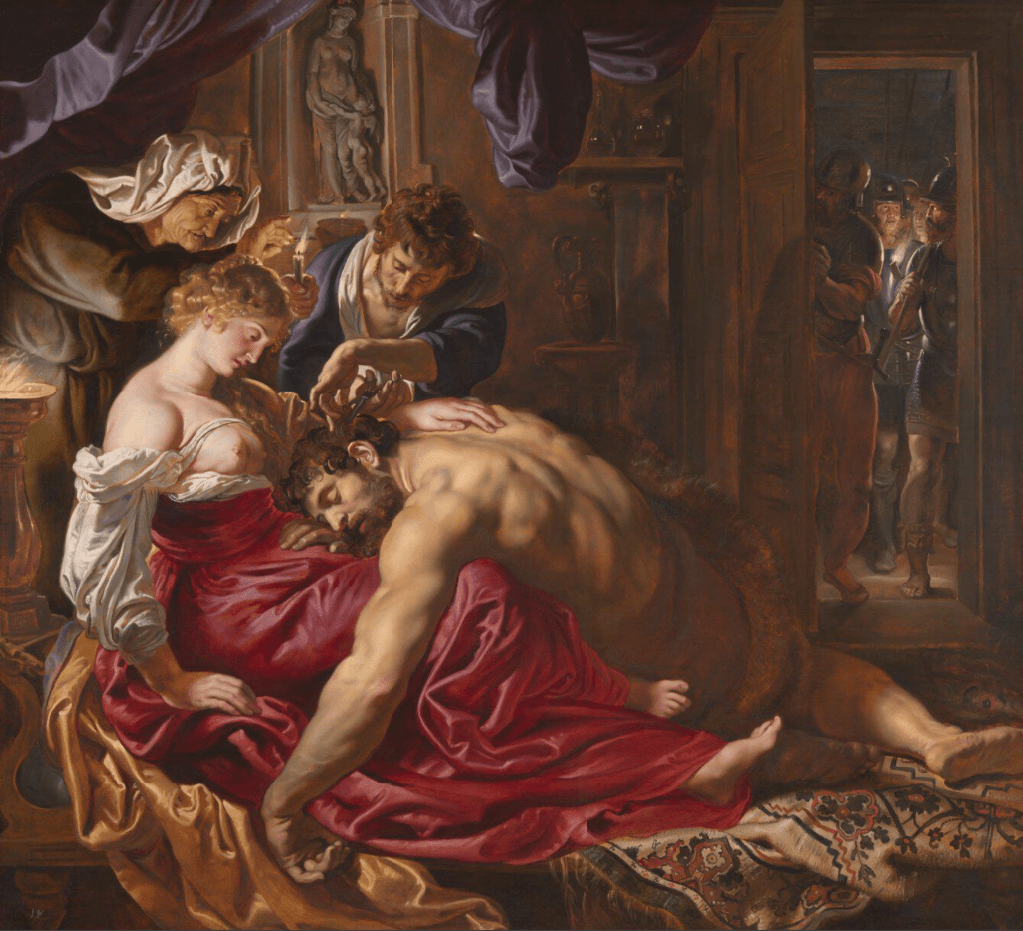

Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah, about 1609-10. The National Gallery, London.

Relatively few people get their own adjective, but as far as Rubens is concerned, that could be a good thing. ‘Rubenesque’ can be positive or negative, or an all-too-obvious attempt to be polite, I suppose, it depends on your attitude. A basic definition would probably be ‘curvaceous, womanly, voluptuous’, while it also implies the sexualisation of the fuller female figure. The curators of Rubens & Women at the Dulwich Picture Gallery – about which I will be talking this Monday, 23 October at 6pm – are aiming to find more nuance in the great Flemish master’s appreciation of the female form. Indeed, they successfully show that he did paint all aspects of womanhood (as I hope to explain) even if (as I shall also discuss) they have stretched their optimism a little far at times. I am currently in Hamburg, though, and have just seen Ingenious Women at the Bucerius Kunst Forum – it’s a superb exhibition, and, I think, a valuable contribution to the study of women as artists. It will be the subject of my talk on 6 November. The week after that I will head back to the National Portrait Gallery for part I of The Georgians. The autumn’s theme of portraiture will then continue with two talks dedicated to the Queen’s Gallery exhibition Holbein at the Tudor Court on Monday 20 and 27 November – they will go on sale soon (keep checking the diary). Both of my November in-person tours are full, I’m afraid (or rather, I’m glad to say…), but I’ll see how those go, plan accordingly, and let you know about future developments.

It’s such a pity that this painting is not in the exhibition in Dulwich – it may not have occurred to the curators, or they may not have been able to borrow it, or there may not have been space. But I really think it does have ‘nuance’ (even if I confess to being wary of the over-use of this increasingly nuance-free term). The story of Samson and Delilah is a complex one, but one of the things I have always admired about this painting – and about Rubens generally – is the brilliance and clarity of the story telling. Even if you don’t know it (and I’m going to pretend that we don’t), you can get a pretty good idea of what is happening just by looking. Before you read any further, have another look and ask yourself what is the first thing that you notice? What is the brightest part of the painting, for one thing?

Four people are gathered in a room, with soldiers just outside the door. It is night time – the sky is black, and there are numerous light sources, from the brazier on the far left to the torches held by the soldiers. A strong man, all but naked, is slumped over the lap of a young, blonde, fair-skinned woman, while an older woman leans over this couple and a second man attends to the hair of the first.

What is the brightest part of the painting? To my eye, it is the young woman’s flesh: her shoulder, neck, and the lower part of her face. And her breasts, of course, which are, for some reason, uncovered. She is reclining on a chaise longue in a flowing, rich red dress, with a similar golden-orange fabric hanging beneath. Above, a deep purple drape enhances the sense that this is a day bed – even at night. It is the brazier on the far left which illuminates the young woman’s flesh, and there is a warm, orange glow at the bottom of the painting, giving a warmth to the legs of the chaise longue, and to the man’s back where it would otherwise be in shadow.

Earlier I said that the soldiers were holding torches – plural. One is immediately apparent, held centrally in the doorway and reflecting off the armour and face of the man holding it. But over his shoulder is a younger man, with no beard, whose neck is illuminated – he must be holding another torch, hidden behind the first soldier. They are pushing their way into the room, the tentative gaze of the man on the left, who has his arm on the door, and the commanding stare of the man on the right – as if he is worried that the other is making too much noise – suggest that this is a form of ambush. To the left of the door a flagon casts a shadow onto a column which supports two glass vessels – decanters – which both reflect and refract the light. It shines on the surface of the glass and illuminates a patch of the wall at the back.

The details at the top of the painting tell us what the story is about. There is second brazier which illuminates the statue above it of an all-but naked woman holding the hands of a boy with wings – Venus and Cupid, the Roman gods of love. This tells us that we are in a pagan environment, and, although Rubens is giving us the wrong religion, we know that this is neither a Christian nor a Jewish household. The purple curtain hangs down, looking almost like over-ripe fruit, next to the glinting decanters, and to the right of them the soldiers appear at the door. This is a story about love (or is that lust?), about drink, and about the army. Meanwhile, the old woman shades her eyes from the glare of the candle so that she can see what is going on.

The light in this painting is playing so many roles. It highlights the details which Rubens has included in the background to tell us what the story is about, and it gives us a sense of character as well. It is the brazier on the far left which illuminates the young woman so brightly, after all. It also enhances her appearance: she is blonde and pale skinned, features which were celebrated as signs of beauty and of refinement throughout western European history. The man is darker skinned, and muscular: it is the fall of the light and the resulting shadows which tell us precisely how muscular he is. He appears to be fast asleep. The head resting on his right hand suggests as much, even if the hanging left arm might imply death (but if Rubens had wanted to show him dead, he would probably have painted him paler). And then there is the fact that his hair is being cut so cautiously: if you don’t want him to wake, you would need to be careful. Why worry how you do it if the man is dead? And while we’re at it, why is she topless? Why is he nearly naked? I’m sure you don’t need to ask: something has been going on… Or has it?

For those of you who don’t know the story, the account I am going to give you is not exactly what it says in the bible (the Book of Judges, Chapter 16) – but it is a version of the story which Rubens’s painting would allow, even if I am taking some licence. Samson was an Israelite hero, enemy of the Philistines (not Christian, not Jewish, but not Roman either, despite Venus and Cupid, but we’ll have to let that pass: the sculpture functions as a non-biblical ‘idol’ suggesting ‘love’ and a religion outside ‘the book’). The Philistines could not defeat Samson, and wanted to know his secret. He clearly liked the Philistine beauty Delilah, so they got her to find out. She invited him round, flirted with him, offered him drink, and implied she might offer him more. He seemed interested, so she offered him more drink, and asked him the secret of his strength. After more flirting, and quite a few more drinks, and, I suspect, a certain amount of pouting on both sides, Samson eventually confided that he had never had his hair cut, and that was where his strength lay. At that point he collapsed unconscious on her lap, she called in the barber – and her maid, it seems – and then summoned the soldiers. End of story – almost… You’ll have to look up what happened next.

The barber does seem to be going about his job in an oddly complex, even awkward, way. OK, so this is a very strong man who doesn’t want a haircut, so you’d have to be careful, but crossing the hands over like this doesn’t seem to be entirely necessary. I can’t help thinking that Rubens was showing off how well he could paint hands: not everyone could. Not only that, but the fall of light is extraordinary. It’s not just the brilliant illumination of the back of the left hand which is holding the lock of hair, or the light glinting across the top of the left forearm, but especially – and remarkably – the shadows that the scissors cast on the forefinger of the right hand which is holding them.

But why is the maid there? She’s not mentioned in the bible. Admittedly, anyone as wealthy and refined as Delilah would be expected to have a maid. However, given the way that Delilah is dressed, and that she has a sculpture of Venus and Cupid in her room, together with the ‘over-ripe’ appearance of the purple curtain, maybe she isn’t really that refined after all. There are quite a few northern European paintings with an old woman watching over a young woman in a low-cut dress (admittedly lower than low-cut in this case), with a young, handsome man (who has been drinking) in attendance. The implication is that the younger woman is a prostitute, the older a procuress, and the man a client. Samson is visiting a prostitute. That’s hardly heroic, you might think, hardly biblical, but think again. Judges 16:1 says ‘Then went Samson to Gaza, and saw there an harlot, and went in unto her.’ However, that’s not Delilah. Verse 4 says, ‘And it came to pass afterward, that he loved a woman in the valley of Sorek, whose name was Delilah.’ Rubens is combining the two verses, and is doing it deliberately. What is the moral of the story, after all? It’s quite simply, ‘Don’t Trust Women’. They may be beautiful, but they will betray you, and hold a power over you which will unman you. It was a commonly told tale. In German this ‘trope’ is known as Weibermacht – the Power of Women. The story of Samson and Delilah is just one of the oft-cited examples. Others include Aristotle and Phyllis, and Hercules and Omphale, you’ll have to look them up. After all, it was the 17th Century, hardly an enlightened era, and this was painted by a man, for a man – Nikolaas Rockox, art collector, patron, and friend of Rubens who served as the Mayor of Antwerp on more than one occasion. He hung it over his fireplace, which explains the warm glow at the bottom of the painting and across Samson’s shadowed back (Rubens, being a brilliant artist, includes real light from outside the painting as part of the narrative, thus making his image look more ‘real’). Here’s a painting from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich by Frans Francken the Younger, painted around 1630-35. It’s called Supper at the House of Burgomaster Rockox, and it shows the painting in its original location.

So that sums it up. Painted by a man, for a man, and it’s the 17th Century, so what do you expect? It’s misogynistic, and Rubens ratchets up the misogyny by suggesting that Delilah was a prostitute – which is not what the bible says. Not much nuance there, really. And not only that.

Have another look at the old woman, and at Delilah. Look at their heads, and the angle of their heads to their shoulders, and the curve of their shoulders. Look at their profiles. This could be the same woman. Delilah may be beautiful now, but the older woman – that’s what you’d end up married to. Don’t trust physical beauty, it won’t last – you should rely on ‘inner beauty’, which she clearly doesn’t have, because she’s so deceitful.

However, let’s think again. Look at the expression on Delilah’s face – she’s not the evil, triumphant villainess, is she? And look at her left hand. Yes, it’s ‘too big’, but no! Rubens did not ‘get that wrong’ – I’ve ranted about his before. I get so annoyed when people get caught up in petty naturalism. This is art, it’s artifice, it’s not meant to be real, it’s meant to show us something beyond what looks ‘right’. And that over-sized hand tells us that she has power, yes, but she also has a care for him: that hand is not oppressing him, or containing him. It is a consoling hand, even if he cannot sense that, given that he’s asleep.

Any great work of art allows of more than one interpretation – just look at all the different interpretations of Shakespeare you’ve seen (well, I hope you’ve seen) – and I think the same is true of this painting. I’ve given you the standard interpretation, let’s call that the ‘Male Chauvinist’ interpretation. I’m using broad brushstrokes here (though sadly not with as much skill as Hals). And surely this interpretation is supported by the bible. Why is Delilah doing this, anyway? It say in Judges 16:5, ‘The rulers of the Philistines went to her and said, “See if you can lure him into showing you the secret of his great strength and how we can overpower him so we may tie him up and subdue him. Each one of us will give you eleven hundred shekels of silver.’ So she was doing it for the money. She was little better than a prostitute.

But did she have a choice? Let’s face it, the whole of the Philistine army is waiting outside the door – she had to do it. Interpretation 2: This is a woman being used as part of the men’s power struggle, a cog in the male machine, a victim of men’s needs. What choice does she have? I’m going to call this the ‘Old School Feminist Interpretation’. As I say, broad brushstrokes. Very broad.

But wait yet again – eleven hundred shekels of silver? Each? That’s a lot of money. And she has the means to get it. Try looking at it this way (interpretation 3): this is a woman using what she’s got to get what she can. She is entirely empowered. This would be the ‘Post Feminist’ interpretation. I used to call it the Spice Girls interpretation (‘I’ll tell you what I want’), but that only tells you how long I’ve been talking about it. I think the painting allows all three interpretations – but not just the first. Look at that hand, how softly it lies on his back, large as it is, and potentially damaging, and look at her face, the regret in her eyes, after she has betrayed him. That’s nuance.

Such a good post Richard! Hope you’re well.

This was sold for a record sum about 20 years ago and it is indeed a stonking picture!

<

div dir=”ltr”>Hope to see you so

LikeLike

Ah yes – money changing hands for beauty, how very apt!

All good, thank you, and enjoying Hamburg… Let’s meet soon to discuss Piero!

LikeLike

<

div dir=”ltr”>Yes please. I need to recce plan for it

LikeLike

Samson and Delilah- I’ve always thought that Samson was in deep post-coital slumber- petit mort- and that Delilah had rather enjoyed herself, hence the tender glance. Her left hand coveys the delight in the feel of a warm muscular back. She and her mother are both enjoying that sense of power we women have when you have conquered a powerful male with your body.

Great article thanks.

LikeLike

Thank you! And yes, that would work… Add another interpretation to the list!

LikeLike

Hi Dr. Stemp. I was surprised and almost disappointed to learn recently that some scholars now believe this painting may not be by Rubens. I note you didn’t mention this possibility. Any thoughts on the certainty of the attribution? Maybe that’s why it’s not at the Dulwich Exhibition? Thank you.

LikeLike

It’s true – some have doubted the authorship, but I didn’t mention it as it wasn’t relevant to my discussion. There are lots of other things I didn’t mention, for that matter, and yet I still wrote too much. However, I have never had any doubts that it is by Rubens, and neither do the curators, conservators or scientific department at the National Gallery. I would trust them rather than myself!

LikeLike

Dear Richard.

Re: Trip to Hamburg

<

div>I have been trying to connect to the Artemisia website to find out details of the trip to Hamburg. The page cannot be found – would you know if this trip still availab

LikeLike

That’s weird, Simon, I haven’t had any trouble accessing it. Try this link:

https://www.arthistoryabroad.com/dates-fees/artemisia/artemisia-trips/hamburg-december-2023/

However, the trip is currently full – someone might drop out, though, so it might be worthwhile contacting them to go on the waiting list.

I’ve just seen that they are thinking of repeating the visit next year, although I’m not sure if I will be doing that one… we’ll see!

LikeLike

Dear Richard

<

div>Thanks for your ema

LikeLike

Hi Richard did you post a blog last Thursday as if you did I did not receive it. Just concerned that I have not lost the link to your blog! Regards and genuinely many thanks for all your brilliant posts and talks .

LikeLike

No, none since Rubens… there’ll be another one this Thursday though!

LikeLike