Hans Holbein the Elder, The Basilica of St Paul, 1504. Staatsgalerie Altdeutsche Meister, Augsburg.

I am looking forward to the exhibition Holbein at the Tudor Court at the Queen’s Gallery, and so wanted to write about Holbein today. This is by Hans Holbein, although probably not the Hans Holbein you are thinking of. Today’s painting is by Hans Holbein the Elder, father to the better known artist, and I’ve chosen this painting as it will be the first image in the first of my two talks about his son, Holbein I: Religion and Reform on Monday, 20 November at 6pm. I want to look at it today because there won’t be nearly enough time to talk about it in detail on Monday. The following week I will talk about the Queen’s Gallery exhibition in Holbein II: Realism and Royalty. While the first talk will introduce Holbein himself, his background (including his training in his father’s studio) and the early part of his career, the second talk will be a thorough investigation of his work in England at the court of Henry VIII. After a week off, during which I will visit Hamburg with Artemisia, I’ll try and bring some colour to the winter months, in the hope that they won’t be as dour as the autumn has been. I’ll look at the spectacular Colour Revolution at the Ashmolean in Oxford, and then Impressionists on Paper at the Royal Academy. It’s all in the diary, of course. Before you read any further, I should warn you that I’ve written a ridiculously long post – possibly the longest ever – but I make no apology for that, it’s a remarkably intricate painting. If you just want to know the precise reason why I chose it, you might want to jump straight to the final paragraph!

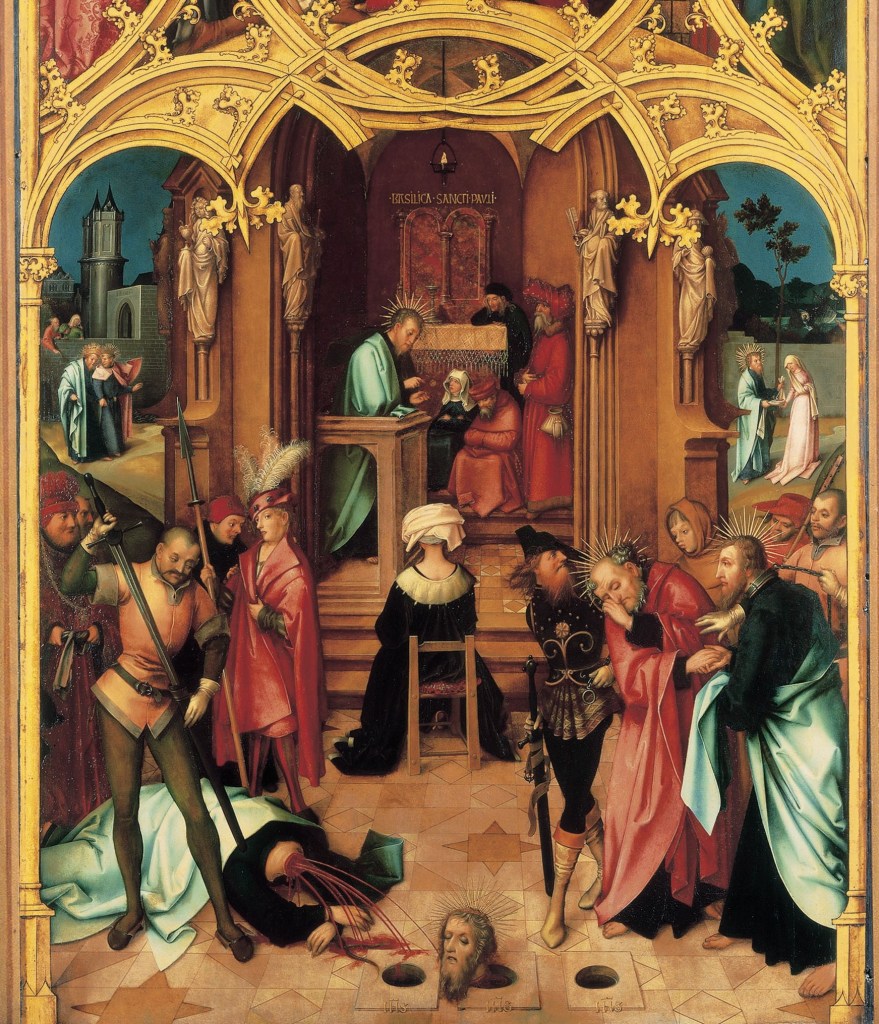

This complex work could be described as a triptych, painted as it is on three separate panels which are then elaborated by arched framing elements painted in gold, typical of German architecture and design in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. It was one of a series of paintings representing different Roman basilicas which decorated the Dominican convent of St Catherine. The building of the former convent now houses the the Staatsgalerie Aldeutsche Meister in Augsburg, which owns the paintings. As well as this one, the Staatsgalerie has a painting dedicated to Santa Maria Maggiore, also by Hans Holbein the Elder, and a San Giovanni in Laterano by Hans Burgkmair the Elder. All are of a similar format, and contain an image representing the church in question, together with scenes from the life of the dedicatory saint. Each also has a scene from the life of Jesus, top centre: we can see that here, and will come back to it below. On a small scale like this it is not that easy to read, but Holbein the Elder makes it perfectly clear where St Paul is by giving him an unusually coloured cloak – effectively a light sky blue, which rings out across the surface in ten different locations. The saint actually features more often than that, though – you could argue that he appears in the painting as many as fourteen times. It’ll be easier to look at each section individually, though.

Although the disposition of stories isn’t strictly left to right, that is roughly how they are arranged. The first, and one of the most important parts of the story, is to be found at the top of the left panel, with St Paul, in his sky-blue cloak and deep turquoise robe, reaching up from a white horse which has collapsed underneath him. He stretches up to the sky, looking towards the beams of light which shine down from heaven, the latter effectively represented by the area above the curved, painted framing element which acts here as the vault of heaven. This is the conversion of Saul (later Paul) as described in the Acts of the Apostles, Chapter 9, verses 3 & 4:

3And as he journeyed, he came near Damascus: and suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven:

4 And he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?

Saul had been on his way to Damascus to punish the Christians on behalf of the Roman Empire, and he was blinded by this brilliant light. The Lord then appeared to a man called Ananias, and sent him to seek out Saul of Tarsus.

17 And Ananias went his way, and entered into the house; and putting his hands on him said, Brother Saul, the Lord, even Jesus, that appeared unto thee in the way as thou camest, hath sent me, that thou mightest receive thy sight, and be filled with the Holy Ghost.

18 And immediately there fell from his eyes as it had been scales: and he received sight forthwith, and arose, and was baptized.

We see the baptism at the bottom left – this is the point that ‘Saul’ takes his Christian name ‘Paul’. Ananias is clearly identified: his name is embroidered multiple times around the hem of his black cape. However, we have to assume that the man being baptised is Saul from the context and from his facial appearance – light brown hair and a medium-to-long beard – as the sky-blue cloak is nowhere to be seen. Holbein the Elder shows himself to be a skilled painter of the male nude, not to mention being aware that baptism in the early Church (and up until the 11th and even 12th centuries) was a matter of full immersion, rather than sprinkling.

Paul appears twice more in this section, though. Behind the font, to the left, is a circular tower, in which Paul is imprisoned – we can see him, his beard and halo, but most clearly, the cloak, through the diagonal bars that prevent his escape. He hands a letter through the bars to a man dressed in early 16th Century clothing. Although Paul was arrested at least 5 times, according to the Acts of the Apostles, this is presumably a reference to the last, in Acts 28:16:

16 And when we came to Rome, the centurion delivered the prisoners to the captain of the guard: but Paul was suffered to dwell by himself with a soldier that kept him.

It is assumed that he wrote many of his epistles – to the Ephesians, Philippians, and Colossians, for example – whilst imprisoned at this time. As a result they are sometimes referred to as the “prison” epistles. The ‘soldier that kept him’ may be the one represented at the top right of the detail above, leading Paul over a bridge to the right of the depiction of Saul on the road to Damascus – the cloak and halo are the most visible parts of this tiny representation.

Paul appears at least six times in the central panel. The Basilica of San Paolo fuori le Mura (St Paul without the Walls) is represented as a stylised cut-away, in a form unlike any it ever took. At the top centre of this detail we can see the chancel arch, with three steps leading up to the chancel itself. Paul is preaching to the gathered assembly – three men and a woman – in front of the high altar. The altarpiece is represented by two Romanesque arches, not unlike the tablets of the law. As with the baptismal font, Holbein the Elder appears to be aware that, early on, the church used the rounded arches of the Romans before it adopted what were, in the north of Europe, still considered to be the ‘modern’ gothic forms (although, as the tracery shows, he was already moving on towards the Renaissance). The name of the Basilica is written above the altar, and the flame of a lantern reminds us that a service is in progress. A second woman sits on a chair outside the chancel, her back to us, but looking in towards the preaching Saint. The piers which flank the chancel arch are enriched with sculptures, three on each side. Those on the far left and right are in profile, and in shadow, so that I, for one, can’t identify them (at a guess, they are Aaron and Moses). However, the four in the light are clearer. From left to right they are St John the Evangelist, carrying a chalice from which a serpent emerges; St Paul himself, anachronistically carrying the sword with which he would later be executed (see below, both in picture and text!); St Peter, with the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven; and St James the Great, dressed as a pilgrim and carrying the cockle shell awarded to pilgrims reaching his shrine in Santiago di Compostela.

The beheading is shown in the foreground. Paul arrives from the right, an iron collar around his neck attached to a chain. He appears to console St Peter, dressed in a red cloak (German artists did not use the colours for saints with which many of us are familiar from Italian art). On the left the executioner sheaths his sword, while the corpse lies below, blood gushing from its neck. The serene looking head sits in the centre of the floor. Two other images of Paul appear at the back left and right: they are also related to the beheading. None of this is in the bible by the way – Paul was very much alive at the end of the Acts of the Apostles. It is all reported in apocryphal sources though. These details are derived from the Golden Legend (to which I have often referred), a collection of stories, some of which were already nearly a millennium old when they were gathered together by Jacopo da Voragine towards the end of the 13th century. As he was being led to his execution, we are told, Paul met a noble woman, a Christian, named Plautilla, and said to her,

Farewell, Plautilla, daughter of everlasting health, lend to me thy veil or kerchief with which thou coverest thy head, that I may bind mine eyes therewith, and afterwards I shall restore it to thee again.

We do not see the kerchief in the beheading itself – the head is left uncovered so that we can see it clearly for our own devotions. But he must have had it. After his execution – and yes, he had been beheaded – this is what he did:

The blessed martyr Paul took the kerchief, and unbound his eyes, and gathered up his own blood, and put it therein and delivered it to the woman.

Hard as this is to believe, it might be easier to understand if we could actually see it. But only some of the elaborate account is illustrated. After the execution, Plautilla confronted the butcher, the man responsible for beheading Paul:

Then the butcher returned, and Plautilla met him and demanded him, saying: Where hast thou left my master? The knight answered: He lieth without the town with one of his fellows, and his visage is covered with thy kerchief, and she answered and said: I have now seen Peter and Paul enter into the city clad with right noble vestments, and also they had right fair crowns upon their heads, more clear and more shining than the sun, and hath brought again my kerchief all bloody which he hath delivered me.

And, if you don’t believe that, on the left (below) you can see Peter and Paul entering the city ‘clad with right noble vestments’ with ‘right fair crowns upon their heads’, and on the right Paul is delivering the kerchief, in which he has ‘gathered up his own blood‘, to Plautilla.

Paul’s head appears twice in the detail above, which is taken from the top of the right-hand panel. At the top left it can be seen on a pole which is held by a man surrounded by sheep, whereas in the centre of the detail it is the Pope himself who carries it with reverence in a white cloth, much as a priest might hold a monstrance containing the consecrated host: it is clearly considered to be a holy relic. Again, we are with the Golden Legend. It seems that, according to the stories, the heads of people who were executed were all thrown into the same valley. At a certain point it was decided that the valley should be cleaned:

… and the head of S. Paul was cast out with the other heads. And a shepherd that kept sheep took it with his staff, and set it up by the place where his sheep grazed; he saw by three nights continually, and his lord also, a right great light shine upon the said head.

The shepherd is the man in red, on the right, whereas the ‘lord’ is to the left of the head, in grey, and wearing a fashionable grey hat – a chaperon. The story continues:

Then they went and told it to the bishop and to other good christian men, which anon said: Truly that is the head of S. Paul. And then the bishop with a great multitude of christian men took that head with great reverence …

The body of the Saint appears centrally in the right-hand panel on its funeral bier, the scantly clad torso echoing the scene of baptism on the left. Having been promised a new life through baptism, Paul now has gained that new life – in heaven – through death: the pairing is deliberate. However, his head has been placed, somewhat unexpectedly, at the corpse’s feet. Yet again, this is a direct reference to a story in the Golden Legend – indeed, it is the continuation of the same sentence:

And then the bishop with a great multitude of christian men took that head with great reverence, and set it in a tablet of gold, and put it to the body for to join it thereto. Then the patriarch [presumably the man shown as Pope] answered: We know well that many holy men be slain and their heads be disperpled in that place, yet I doubt whether this be the head of Paul or no, but let us set this head at the feet of the body, and pray we unto Almighty God that if it be his head that the body may turn and join it to the head, which pleased well to them all, and they set the head at the feet of the body of Paul, and then all they prayed, and the body turned him, and in his place joined him to the head, and then all they blessed God, and thus knew verily that that was the head of S. Paul.

Yes, this is an old translation, and I love it – it is the version by William Caxton, no less, and was published in 1483. ‘Disperpled’ is an obsolete word for ‘scattered’. I’m going to start using it more.

Holbein the Elder does not attempt to show the body turning to join the head… but that is hardly needed. To right we can see Paul’s final appearance on the altarpiece, being lowered from a window in a basket, and we are back with biblical authority: Acts 9:23-25. Paul – still known here by the name he grew up with, Saul – has been very successful and the local Jews are not happy that so many people have been converted:

23 And after that many days were fulfilled, the Jews took counsel to kill him:

24 But their laying await was known of Saul. And they watched the gates day and night to kill him.

25 Then the disciples took him by night, and let him down by the wall in a basket.

We see the act of escape on the far right of the painting, opposite the image his imprisonment on the left of the left panel. This symmetry is a metaphor, surely, of the soul being freed from its earthly prison, the body, as a result of death. There is one final section of the painting to look at.

At the top, almost as if mounted on the vault of San Paolo fuori le Mura, we see the mocking of Christ, and the crowning with thorns. This is taken from Matthew 27:28-29. There is a very similar account in Mark, although Holbein the Elder has definitely drawn on Matthew, as Mark says that the robe was purple, whereas Holbein the Elder has clearly chosen scarlet:

28 And they stripped him, and put on him a scarlet robe.

29 And when they had platted a crown of thorns, they put it upon his head, and a reed in his right hand: and they bowed the knee before him, and mocked him, saying, Hail, King of the Jews!

The man kneeling beside Jesus and handing him the reed is particularly elaborately dressed, with enormous, richly embroidered sleeves and intricately patterned hose – as if Holbein the Elder is making fun of contemporary excesses in fashion. But then the soldier at the back right – one of two men ramming down the crown of thorns with a long stick, because it is too thorny, too dangerous, to hold – is hardly less ornately dressed, with a regularly studded jerkin attached at the front by a number of red leather and gold buckles. Jesus, meanwhile, maintains a serene, transcendent expression. On either side grotesque figures gesticulate – scribes and pharisees, presumably, although the man with the peaked and domed hat is presumably Pontius Pilate, given that he holds a commander’s baton (although he could be Herod, as King). The hat itself is based on one worn by the Byzantine Emperor John VIII Palaeologus to the Council of Florence in 1438, which Holbein the Elder could have known about from a medal by Pisanello.

However, whatever is in the painting, and however much I have said (without even starting on the style of the depiction, the artist’s superb control of composition, use of colour, or ability to direct our eyes around the painting), it does nothing to explain why I wanted to look at this particular work by Hans Holbein the Elder, rather than any other, in order to introduce his son. Let’s look again at a detail of the baptism of St Paul in the left-hand panel.

Paul stands demurely in the baptismal font, his hands lowered to preserve his modesty as he looks down at Ananias conducting the service. To the right there is a man looking out towards us dressed in early 16th Century clothes – a dark grey coat over a black jacket. In front of him stand two boys, identically dressed in light grey-green coats, with various objects attached to their belts. The one on the right is taller, and has longer hair, and seems to be looking after his younger brother: he rests his left hand on his younger brother’s left, and puts his right hand on the boy’s back. The younger boy rests his right hand on his own shoulder – and possibly on his father’s right hand, which we can’t actually see. ‘Dad’ seems to indicate the younger boy by pointing with his left forefinger. Dad is none other than Hans Holbein the Elder, and on the right is his first son, Ambrosius, who was born around 1494, and whom Hans taught to paint. But then, he taught his second son to paint as well. Born around 1497 he must have been six or seven when the Basilica of St Paul was painted in 1504. This is Hans Holbein the Younger, and for a long time this was thought to be his first appearance in the History of Art. Both dad and brother seem to focus on him. Was there any way of knowing that he would grow up to be more famous than the both of them? Could he already have been showing extraordinary talent at the age of seven? It seems hard to believe it, and yet… who knows? Why else is dad pointing at him specifically? Franny Moyle, author of the recent biography of Holbein, believes that he was considered a child prodigy, and may even have been educated by the nuns of St Catherine’s (whose building now houses this painting). She has even identified an earlier portrait of the boy in the same museum, with the five-year-old Hans holding a fish next to Jesus in the Feeding of the Five Thousand – he clearly was a golden boy. But we will look at that painting, and what our seven-year-old did next, on Monday.

Hi Richard

I really enjoyed your article.

This triptych is amazing.

What fun!

It’s like an early 16th Century game of Where’s Wally.

Fiona Marshall

LikeLiked by 1 person

The ubiquitous St. Paul is disperpled throughout:)

Fiona M

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Dr Stemp,

Thank you so much for this fascinating analysis of ‘The Basilica of St Paul’. I really appreciate the trouble you went to in order to describe and explain, in detail, all the scenes which are depicted here. It was really helpful that you showed quotations from relevant descriptive passages from the sources.

How wonderful to think that Holbein Senior recognized the genius of his young son and showed it in his work.

I love the word ”disperpled” too and must get into the habit of using it. As a female in my late 60s my thoughts are often ”disperpled”!!

I look forward to your talk on Monday and will book it as soon as I’m sure I’ll be able to attend.

Many thanks again for your wonderful blog.

Kind regards,

Eithne White.

https://www.avast.com/sig-email?utm_medium=email&utm_source=link&utm_campaign=sig-email&utm_content=webmail Virus-free.www.avast.com https://www.avast.com/sig-email?utm_medium=email&utm_source=link&utm_campaign=sig-email&utm_content=webmail <#DAB4FAD8-2DD7-40BB-A1B8-4E2AA1F9FDF2>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Eithne – I couldn’t make head nor tale of it initially, but the Golden Legend did its usually trick!

LikeLike

Great talk around all this last evening and looking forward to Part II. In the diary! Thank you continued thanks for all you do. Tim

Especially appreciate the ‘side bars’ on technique during the talk yesterday! T

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for the lecture last evening. Especially appreciate the sidebars on technique and approach these artists used. Look forward to part two next Monday. We are blessed with both blog and the talks. Tim

LikeLiked by 1 person