Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People (‘Ecce Homo’), state V, 1655. National Galleries of Scotland.

Happy New Year! And greetings from Liverpool – I’ve started the process of moving here, which may take a while to complete… In the meantime, the world of ‘online’ remains, and I will start afresh this Monday, 8 January at 6pm with Part 1 of my introduction to the exhibition The Printmaker’s Art: Rembrandt to Rego. That link will take you to a reduced-price ticket for both talks, but if you are only interested in one, these two links, 1. From Rembrandt… (8 January) and 2. …to Rego (15 January) will let you to book for each talk individually. The exhibition is drawn from the collections the National Galleries of Scotland, and is housed in the Royal Scottish Academy Building in Edinburgh. Although it is organised thematically, according to the different techniques of printmaking, I am currently enjoying the process of deconstructing it, and rearranging the exhibits in chronological order to see if we learn anything in the process – a sort of ‘History of Printmaking’, if you like. After these two talks I will take a week out (to see ‘Rothko’ in Paris), but will return to consider two rather lovely exhibitions currently at the National Gallery – those dedicated to Pesellino (29 January) and Liotard (5 February). I am also planning some more in-person tours for the end of January, and will give you more information soon: keep your eyes peeled on the diary for that, and for links to book the Artemisia trips to Ravenna and Delft which I will be leading in April and May respectively.

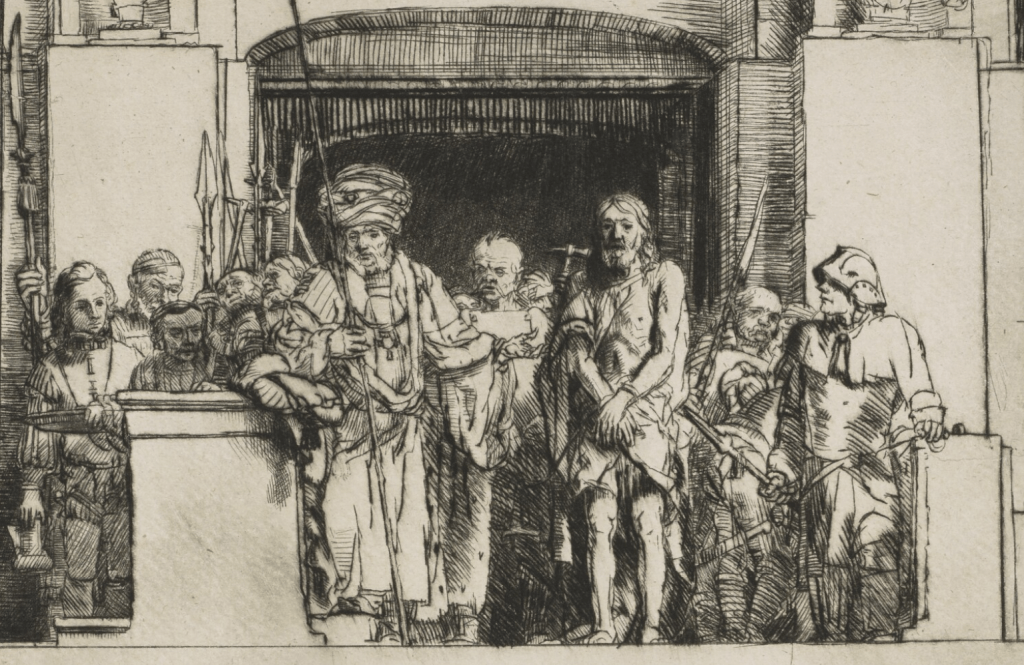

Included in Monday’s talk will be an explanation of each different printing technique, and of the specific language used by print afficionados. For today, though, I just want to think about one of each: this is a drypoint, and we are looking at the fifth state of the print – out of a total of eight. I’ll explain both of these terms once we’ve had a chance to think about the image itself. Rembrandt is illustrating a very specific text from the bible – the Gospel according to St John, chapter 19, verse 5 (or John 19:5, to use the usual abbreviation). As usual, I am going to give you the verse – and those preceding it – so we can see precisely what it is that Rembrandt is interested in. It is Holy Week, Jesus has been arrested, and brought before Pontius Pilate.

19 Then Pilate therefore took Jesus, and scourged him.

2 And the soldiers platted a crown of thorns, and put it on his head, and they put on him a purple robe,

3 And said, Hail, King of the Jews! and they smote him with their hands.

4 Pilate therefore went forth again, and saith unto them, Behold, I bring him forth to you, that ye may know that I find no fault in him.

5 Then came Jesus forth, wearing the crown of thorns, and the purple robe. And Pilate saith unto them, Behold the man!

In the Vulgate – St Jerome’s Latin version of the bible – the words ‘Behold the man’ are given as ‘Ecce Homo’ – which gives this particular image its name.

Rembrandt imagines a platform in front of a large, civic building with wings projecting to the left and right, or maybe inside an open courtyard. People have gathered in front of the platform as witnesses to the event, entering from a colonnade to the left, or coming down a staircase on the right. Others watch from windows in the façade, and a few more stand on a balcony to our right. Christ and Pilate stand near the front of the platform, framed by the dark shadows of an arch through which they have presumably entered. They are surrounded by a number of soldiers and officials.

Pilate wears a large turban – an exoticizing touch, used as a sign that we are not in Europe. Pilate was, after all, the Roman Prefect in Judea, although having said that, his first name, ‘Pontius’, could imply that he came from southern Italy. However, that is by no means certain: Roman citizens could come from anywhere within the Empire. He holds – as he often does in northern European images – an incredibly long and thin staff of office. Despite the non-European headgear, his cloak is lined with ermine, a European symbol of royalty, used here to remind us of his high status. We can see the lining thanks to the gesture of his left hand, which is held out towards Jesus, as if to say, ‘Behold the man!’ – ‘Ecce Homo’. The weapons and costumes of the group surrounding the protagonists fall somewhere between non-specific ‘biblical’ imaginings and the observed reality of the renaissance and baroque. Rembrandt is giving a sense of the near past, something the original viewers of the print might have been aware of, even familiar with, but nevertheless leaving a sense of difference: this is not exactly here and now, but something the viewer could understand. Jesus’s costume is indistinct, but he certainly does not have the crown of thorns, as John’s gospel suggests that he should, and if he is wearing a purple robe it is unusually short: his knees and calves are clearly defined. From this detail alone I would suggest that Rembrandt is more interested in the mood of the event than a precise illustration of the text, and in particular, he is interested in Jesus’s vulnerability.

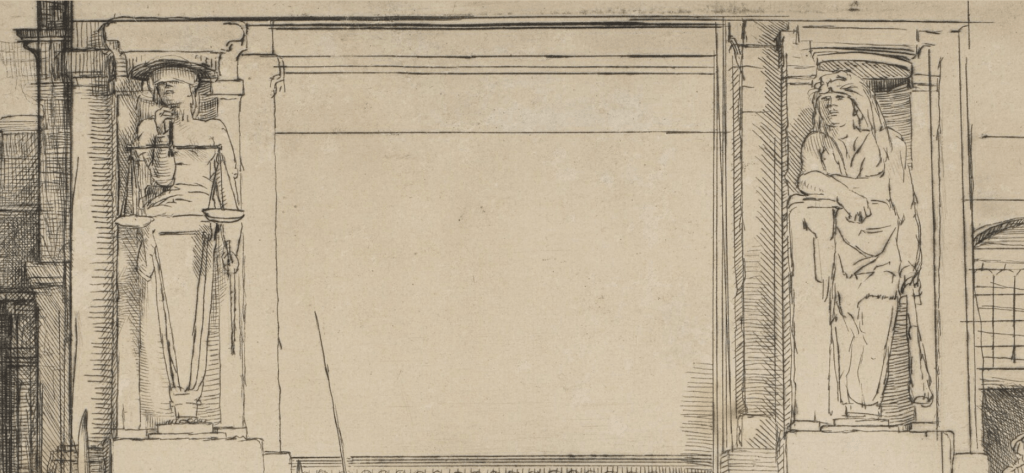

Above the archway is a blank area of wall framed by two pilasters, each of which serves as the backdrop to a sculpture. On our left a blindfolded figure holds a pair of scales, while on the right a second holds a club and wears a lion skin. These are personifications of Justice and Fortitude. Justice, considered to be unprejudiced, is therefore shown as blind, and holds scales to weigh up – albeit symbolically – the degrees of good and bad. Fortitude is represented by the classical hero Hercules, who slayed the apparently invincible Nemean lion, and thereafter wore its skin for his own personal protection. These are precisely the sorts of virtues you would find on the façade of a Dutch town hall. In Amsterdam, what is now the Royal Palace was originally designed by Jacob van Campen as the town hall. Construction took place between 1648 and 1665, although it was sufficiently far advanced to be officially ‘opened’ in 1655. On the façade facing Dam Square, a figure of Justice stands to the right of the pediment, with Prudence (rather than Fortitude) standing to the left. Given that Rembrandt was working on this print in the year that the Palace was opened, it may well be relevant. This is just one of the ways in which Rembrandt tells his story: by finding contemporary equivalents for far-off, biblical events, thus making the narrative more comprehensible for his contemporaries.

The window to the left of the façade is another example: it is designed with contemporary, classical-style architecture, including framing pilasters, the one on the left including a relief carving of a lily. Looking out of the window is a woman in contemporary (i.e. 17th Century) dress. To the right of her is a reminder that this is an ‘official’ building: there are soldiers lurking in the shadows.

And now for those technical terms. This is a drypoint. You can see that from the blur around most of the lines in this detail, most notably across Jesus’s chest. Elsewhere the blur creates a sense of extra shadow. This blurring is a feature of drypoint. Unlike engraving, in which a sharp, V-shaped tool called a burin is used to cut out distinct slivers from a copper plate, thus creating a groove with clear-cut edges, in drypoint a sharp, hard, pointed metal tool – a needle or stylus – is used to gouge out a groove. The material from the groove is pushed to one side, a bit like soil when ploughing, and remains on the plate as a bur. This bur – effectively a ridge of gnarled-up copper – gathers ink in the pits of its rough surface alongside the ink which gathers in the groove which has created it. When the image is printed this results in a blurred line. With engraving, because the burin makes a far more clear-cut groove, the lines are sharper, more clearly defined. However, with each successive print that is taken from the plate of a drypoint, the bur is gradually worn down – so later prints from an edition (I’ll get to that term on Monday – or in week 2…) are less blurry than the earlier prints.

Having dealt with one of today’s terms – drypoint – let’s move on to the second: what is a state? Compare and contrast the following two images:

It is relatively rare that a work of art is completed in one session. Admittedly some artists – notably modernists and beyond – make such ‘spontaneity’ a feature of their work. But on the whole, art is a process of trial and error, of gradual development. This is certainly the case with printmaking. It’s worthwhile remembering that, with a print, the artist is almost always working back-to-front: the process of printing results in a reversal of the imagery. Having worked on the plate the artist might want to get some idea of how the finished design will turn out – so they ink the plate and pull (i.e. make) a print. The resulting image may not be entirely satisfactory, in which case the plate could be reworked, and a second print could then be pulled. The first print would be state I, and the second, state II. For the Ecce Homo Rembrandt apparently went through a series of eight states, with the above two being states V and VIII. What is interesting about this is that we might have assumed that states I – VII were not satisfactory, which is what led to them being reworked. So why do examples still survive? Why were they not discarded? Well, drawings and sketches are of interest because they show the artist’s mind and hand at work, and the same is true of the different states of a print: the developmental process is of interest in itself. In addition to this, different collectors have different tastes, and each might prefer a different state – so keeping examples of all the states can maximise the artist’s potential sales. The numbering of the states post-dates the event: it could be that there were originally 10 different states of this image, but so far art historians have only identified 8, based on what is known now from surviving collections.

The Dutch Republic of the 17th Century was important for many reasons. Having broken away from Spanish Rule, it became officially and predominantly Protestant, as opposed to having Catholicism imposed by the Spanish. It was ruled by a rising merchant class who wanted to show off their wealth. They had the world’s first, modern stock market (and the first stock market crash), and they also had what was effectively the world’s first art market, not to mention the first dedicated ‘collectors’ – and collectors can be particularly obsessive. Not only might they want an example of the work of each of the most important artists, but they might also want examples of each of those masters’ prints, and even, an example of every state of each of those masters’ prints. By pulling multiple prints of each state, an artist was more likely to make more money from them – providing they had the right client base, of course.

But what are the differences between these two states? I’m going to leave you to consider this at your leisure, while pointing out the most obvious, and most remarkable, which can be seen at the bottom of the image. Again, compare and contrast.

The difference is striking and clear. In the fifth state there is a crowd of onlookers of all ages in front of the platform. They are mainly men, with a few women, who are looking after babes-in-arms and toddlers. A single man steps in from the right, his shadow falling onto the platform, and another figure – possibly also male – leans round at the far left. In the eighth state it is only these last two which survive. The others have been burnished out (the process of polishing the plate smooth again), and replaced with shadowy texture, and two deep, dark and ominous arches. A ghostly figure remains, central, and looking out at us – but Rembrandt seems to have lost interest in either defining this figure more fully, or removing it entirely. The effect of the change is to increase the focus on Jesus, and to make the image as a whole darker, starker, and more intense. There is now no one between us and the protagonists – which puts us in the position of the crowd: we are now the onlookers. In all four gospels a Passover ritual is related: the people present were allowed to choose a prisoner to be freed – Jesus, or the notorious prisoner, bandit, or even murderer Barabbas. They choose the latter. By removing the crowd, Rembrandt puts us in the position of those who choose. He assigns the blame to us. It’s a chilling idea.

Elsewhere he gouges again and again into the copper plate, adding more details, and deepening the shadows. One effect is to make Christ appear more haggard, more fragile, and more of a victim. It is darker, and more emotive. And yet the choice of Barabbas will always be the same.

A cold time of year to move, but… best wishes.

LikeLike

Thank you. Cold, and very wet. It rained for the first 48 hours…

LikeLike

Dear Richard,

Happy New Year.

<

div dir=”ltr”>Is there any other link th

LikeLike

Thank you, Amita – and to you too! Is this the whole message, or were you asking about a link? Some of the message might have disappeared…

LikeLike