Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Proserpine, 1881-82. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

With the appalling news that over the next two years the Birmingham City Council will be cutting its arts funding to leading institutions by 100%, I am especially looking forward to talking about the exhibition Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement this Monday, 26 February at 6pm – I hope it will persuade you to see a superb exhibition and support at least one of the city’s cultural institutions. As far as I can tell, the cuts do not apply to the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, but my guess is that they are using this paying exhibition of their own extensive holdings to build up some money for a rainy day, just in case – even if it was planned months, if not years, before the recent news. The exhibition has toured the States with enormous success, as has another which has just opened at Tate Britain: Sargent and Fashion (which I will be talking about the following week, 4 March). On 11 March (keep an eye on the diary) I will cover the Royal Academy’s Angelica Kauffman, an exhibition I’ve been looking forward to since it was postponed during lockdown: at the time it seemed like it had been cancelled for good. There are still a couple of places available for my In Person Tour NG03 The Northern Renaissance at the National Gallery on Wednesday 13 March at 11:00am and Wednesday 13 March at 2:30pm, but the others are full – more will follow, I hope, in April.

Rossetti painted eight versions of Proserpine, not all of which have survived. This is the last, completed in the year he died, 1882. There is also a version in coloured chalk. Why was he so obsessed with the subject? The model is his muse and lover Jane Morris, and a consideration of the painting and its place in their lives might help to explain his infatuation with the story. I’ve started with an image of the painting in its frame. As we will see on Monday the total image was a key element of Pre-Raphaelite practice, but all too often museums focus on the paintings themselves while cropping the frame – an essential element in the way the work is seen, and often the creation of another (or even, the same) artist-craftsperson. The tall thin format is enhanced by the almost plain bands of gold on either side, giving us the sense that we see Proserpine – to use the painting’s title – through a narrow doorway. She looks out to our left, apparently unaware of our presence, clasping something to her chest, and holding one wrist in the other hand. Her full, sea-green dress falls over a ledge on which stands a lamp or censer, and a whisp of ivy climbs the wall at the back, passing the edge of a brilliant patch of light. Pieces of paper appear to have been stuck to the painting at top right and bottom left.

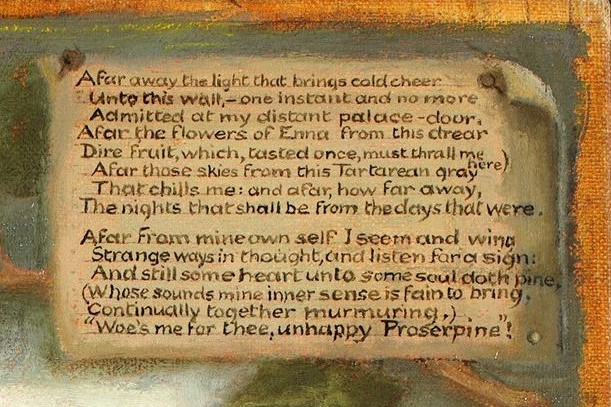

This detail comes from a photograph of the painting taken out of its frame – we can see the edges of the canvas which have not been painted. This close we can also see that the piece of paper at the top right, although painted, appears to be attached, trompe-l’oeil fashion, with pins at the corners, although these don’t stop it from curling back at the top right. It is tightly inscribed with the fourteen lines of a sonnet. The paper is affixed over the ivy, which spreads behind the head of Proserpine, the woody stem a subdued version of her flaming red hair, the leaves echoing her green eyes. The sonnet is Rossetti’s own, and entirely legible – here is a detail, and a transcription.

Afar away the light that brings cold cheer

Unto this wall, – one instant and no more

Admitted at my distant palace-door

Afar the flowers of Enna from this drear

Dire fruit, which, tasted once, must thrall me here.

Afar those skies from this Tartarean grey

That chills me: and afar how far away,

The nights that shall become the days that were.

Afar from mine own self I seem, and wing

Strange ways in thought, and listen for a sign:

And still some heart unto some soul doth pine,

(Whose sounds mine inner sense in fain to bring,

Continually together murmuring) —

‘Woe me for thee, unhappy Proserpine’.

Given that sonnets are always fourteen lines, they can be remarkably varied. This one is presented as two verses, the first of eight lines, the second of six. The rhyme scheme is intriguing. For the first verse, A-B-B-A-A-C-C-A, implies a particularly heightened pronunciation of ‘were’ at the end of the eighth line – more like ‘weir’. The rhymes of the second verse, D-E-E-D-D-E, tell us that Proserpine should rhyme with ‘sign’ and ‘pine’. Like ‘were/weir this suggests to me that Rossetti and his associates spoke very posh English. Rather than Proserpine, the Greeks called her Persephone, and she was the daughter of Demeter. One day, picking flowers in Enna (as mentioned in line 4) she was abducted by Hades and taken to the Underworld. For the Romans she was Proserpina, her mother Ceres, and the God of the Underworld was Pluto. The Latin names might make more sense given that Enna is in the centre of Sicily, and Rossetti was essentially an Italian born in England. However, although it is now part of Italy, it is worthwhile remembering that Sicily played an important part in the Greek world. Indeed, some of the best surviving Greek temples are to be found on Sicily. But maybe that’s beside the point.

According to Ovid, Pluto had been checking the roof of his realm after Phaeton had crashed to the earth when Cupid shot him with a golden arrow. Proserpina, who was indeed picking flowers with her friends, was the first living thing he saw. He fell madly and desperately in love with her, grabbed her and headed back home. Ceres mourned the loss of her daughter, and as a result, given that she was the Goddess of Agriculture and Fertility, all the plants started to die. Eventually she got permission to reclaim her daughter from the Underworld on the condition that Proserpina had not eaten anything. However, the pomegranate was her undoing. She had eaten just one seed (according to some sources) but that was enough to force a compromise: for six months a year she must remain in the Underworld. For the rest of the year she could return to the light of the sun. Once above ground, Ceres relented and everything started to grow again, but when Proserpina had to return to the Underworld, the creeping death set in once more. And so on, year after year – hence the cycle of seasons, Autumn, Winter, Spring and Summer. As with everything in Ovid, everything is always subject to change, to Metamorphosis.

Proserpina holds the pomegranate close to her chest, and the gash in its skin, from which she has eaten, approximates to the red of her lips, not to mention her hair. And as well as the leaves, her eyes also echo the colour of her dress.

Her right hand holds her left wrist, the elongated, but elegant fingers holding lightly, and suggesting a sense of regret – if only she could have pulled the other hand away, and not eaten. The fingers of the left hand, equally elongated, equally elegant, also touch the pomegranate delicately: a melancholy memory it would be better to forget, but which cannot be let go.

Pinned to the parapet is a thin scroll bearing the signature DANTE GABRIELE ROSSETTI 1882. Above it, on the marbled surface, a space left clear by the abundant green fabric, which appears to have been swept to the side specifically for this purpose, is occupied by a censer. It’s bittersweet perfume matches the melancholy of the image. So many of our senses are engaged: sight, as Proserpina looks out to the illuminated world (and we look in to the painting), touch and taste, given that Proserpina holds the pomegranate and remembers its flavour, and, with the censer, also smell. Maybe even hearing as well, if we imagine someone reading us the verse, telling us the story. The censer reminds me of the words of the carol We Three Kings, which tells of the interpretation of the gifts brought to the baby Jesus: ‘Incense owns a deity nigh’. That was certainly the reason Rossetti included it here. In 1877 he wrote to W. A. Turner, a collector who had bought an earlier version of the painting:

“The figure represents Proserpine as Empress of Hades. After she was conveyed by Pluto to his realm, and became his bride, her mother Ceres importuned Jupiter for her return to earth, and he was prevailed on to consent to this, provided only she had not partaken of any of the fruits of Hades. It was found, however, that she had eaten one grain of a pomegranate, and this enchained her to her new empire and destiny. She is represented in a gloomy corridor of her palace, with the fatal fruit in her hand. As she passes, a gleam strikes on the wall behind her from some inlet suddenly opened, and admitting for a moment the sight of the upper world; and she glances furtively towards it, immersed in thought. The incense-burner stands beside her as the attribute of a goddess. The ivy branch in the background may be taken as a symbol of clinging memory”

Looked at again as a whole, the painting could easily be titled ‘Clinging Memory’. Notice how two of the ivy leaves to the left of Proserpina’s forehead reach up to the top left corner, while the branch below starts from the right, below them, and then continues down the painting curving left, and then back again to the right. The ivy echoes the flow of her head, neck and then dress, the last of these trailing off into the bottom right corner of the painting just as the last, tiny leaves of ivy trail off at the bottom right of the stem. She echoes the ivy, she too is ‘clinging memory’.

It is, surely, the archetypal Pre-Raphaelite painting – a good story, beautifully told. And Jane Morris is surely the archetypal Pre-Raphaelite woman, with her flowing red hair and pouting red lips. This is so much the case, that I often used to wonder how much ‘art’ was going on here? How much was Rossetti making her into his ideal through his use of paint? On seeing photographs, though, you realise there was no invention. She really did look like this. You just have to compare the painting with this detail from a photograph taken by John R. Parsons in 1865, one of a series in which Morris was posed by Rossetti himself.

This print, together with many others, is in the collection of the V&A. You can click on that link – or here – to see them all. I sometimes wonder if even Rossetti couldn’t quite catch how remarkable she was. In 1881, the year today’s painting was begun, Henry James met Jane Morris in Italy, and wrote to a friend that she was ‘strange, pale, gaunt, livid, silent, yet in a manner graceful and picturesque’. He also remarked that she was not without her merits. ‘She has, for example, wonderful aesthetic hair’.

Born Jane Burden in Oxford, she was the daughter of a washerwoman, and a stablehand. Rossetti was in the City of Dreaming Spires in 1857 to paint murals in the Oxford Union, and it was at this time that he got to know second-generation Pre-Raphaelites Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. Having met her in the street, and being struck by her beauty, Burne-Jones and Rossetti asked Miss Burden to model for them, but it seems that she didn’t even know what they meant. However, once she’d found out, she agreed, and the rest, as they say, is history. But not the history one might have expected. It was William Morris who proposed to her: the two were married in 1859. Rossetti would marry Elizabeth Siddal the following year, but sadly that was not to last: within two years she had died. Having modelled for him before their respective marriages, Jane Burden – now Morris – returned to Rossetti’s studio in 1865. Their mutual interest was rekindled, blossoming into a full-blown affair. In 1871 William Morris visited Iceland, while his wife and friend, Jane and Gabriel, leased Kelmscott Manor, not so very far from Oxford. From then on her winters were spent in London, summers in the country. Kelmscott was hardly Enna, but there were flowers in an extensive garden. London was not exactly the ‘Tartarean grey’ of Rossetti’s sonnet – even if it was one of the most polluted cities in the world at the end of the 19th Century. Nevertheless, the parallels are clear. Jane continued to be Rossetti’s main model and muse, and even though their affair did not last so very long after that idyllic summer of 1871 (‘the light that brings cold cheer’?), they were friends until his death in 1882. In the painting, Proserpina looks out at a flash of light from the world of the living, while Dante Gabriel Rossetti remembers his moments in the light with Jane, who was trapped in her loveless marriage. It wasn’t William’s fault, and he certainly didn’t abduct her. He was a totally devoted husband, and devastated by her betrayal with his good friend Rossetti. He coped with it all with extraordinary dignity. But, towards the end of her life, Jane quite clearly stated that she had never loved Morris, even if marriage to him had changed her life. Given the chance, she would have done it all again. Year after year.