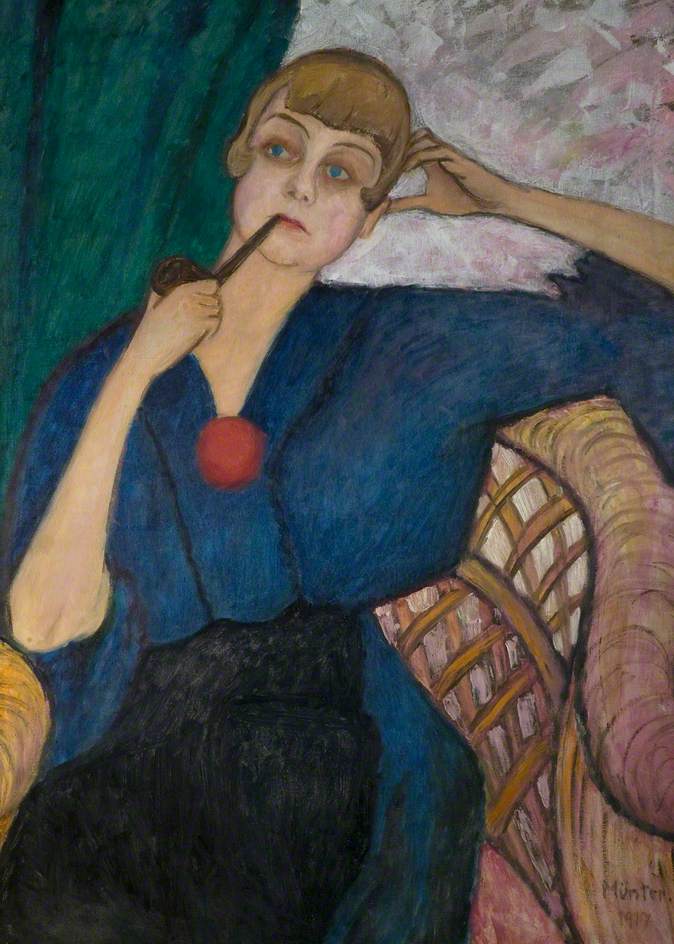

Gabriele Münter, Portrait of Anna Roslund, 1917. New Walk Museum and Art Gallery, Leicester.

I’m looking forward to talking about the Expressionists exhibition at Tate Modern this Monday, 20 May at 6pm, but as I’m currently in Delft with Artemisia I’m going to re-post something I wrote for Making Modernism, the Royal Academy’s 2022 exhibition focussing on four women who were themselves Expressionists. Two of them feature in the current show – Gabriele Münter and Marianne von Werefkin – and both are superbly represented. A couple of paintings are the same, but on they whole the exhibition features works I have never seen before, including several I really wanted to see as a result of the RA show, together with paintings by Kandinksy, Marc and Macke, the last of whom I am especially enjoying. The following week I will look at another redoubtable woman, Yoko Ono, also on show at Tate Modern, and then (although it’s not on sale yet) Michelangelo: The Last Decades, introducing the recently-opened exhibition at the British Museum which must be the must-see show for the summer. Beautifully selected and curated, it is also designed with great clarity and a wonderful understanding. Keep your eye on the diary for that.

There are still places for some of the last of this season’s In Person Tours:

Monday 17 June at 11:00am: NG05 – Siena in the Fifteenth Century

Tuesday 18 June at 2:30pm: NG07 – Perugino and Raphael (afternoon)

The day after, on 19 June at 1pm, I will be lecturing at the Wallace Collection. The talk is free, and you can either attend in person, or online, but I would love it if you could come and pack out the room: I would finally get to see you all! Entitled Getting Carried Away with Michelangelo and Ganymede it will explore the relationship between Michelangelo and the young nobleman Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, and will look at the refined drawings, heartfelt letters and complex poems which passed between the two. If you’re coming in person you can just turn up on the day, but for online viewing you should book a ticket via the blue links above. It will also be recorded, apparently, and available to view for the following week or so.

Meanwhile, today I want to look at the ‘Poster Woman’ of Making Modernism, Anna Roslund, as painted by Gabriele Münter. I would say ‘Poster Girl’, but shortly before I wrote this post back in November 2022 I had had my wrist slapped for my careless use of language…

I’m afraid I can tell you relatively little about Anna Roslund herself, but we get a strong sense of her character just by looking at this portrait. Apart from anything else, how many women have you ever seen smoking a pipe? I know there are some famous examples in history, but I can’t for the life of me remember who they are. ‘Women smoking’ is something one didn’t used to see ‘back in the day’ (i.e. a long, long time ago), and ‘women smoking a pipe’ make up an even smaller sub-group. This bold gesture is combined with an open pose, left arm resting on the arm of the chair, with her head resting on her left hand. The right arm is tucked in, holding the pipe to the mouth. Add to that the strong, bold colours of the outfit, royal blue and black, heightened by the bright red of the pom-pom (?) in front of her chest, and you have a strong sense of individuality, the image of self-confidence.

Anna Roslund has the clearest, light-blue, piercing eyes, and a stylish haircut, apparently bobbed with a fringe (although we can’t see what it’s like behind), which makes me think more of the 1920s than 1917. She is clearly a serious, thoughtful woman, her head tilted to one side and her eyes gazing into the middle distance some way above our left shoulders. Like Rodin’s Thinker, with his chin on his fist, or Dalí’s Narcissus, who we saw a while back, his chin on his knee, the head leaning on the hand adds to the sense of contemplation, albeit in a different way. Each finger is clearly demarcated (although the little finger is oddly truncated – I don’t know whether that was an anatomical fact, or an artistic abbreviation), and there is a clear space through to the light background. Presumably, given the curtain, this is a view through a window, with broad, light brushstrokes of white and pink over a darker ground, giving an idea of a light, but cloudy sky. The curtain itself, in a deep turquoise, is angled parallel to the tilt of the head, and completes the ‘virtual’ pyramid which gives this composition – and Anna Roslund – stability, and strength of presence. Another note of stability is the horizontal of the arm, marked strongly by the contrast between the upper edge of the blue sleeve and the light background (and notice how the thumb and fingers echo shapes of the arm and head).

Roslund is clearly comfortable in this chair, and I love the way in which the curve of her right shoulder, clad in blue and enhanced by a subtle black outline, echoes the curve of the left arm of the chair – it is as if she is a completion of the chair on that side. The chair itself, with the yellow arm given texture and form by the darker brushstrokes, is painted in a similar technique and colour to Van Gogh’s more famous example, a symbolic self portrait (having said that, now that I have posted the pictures the chair looks more violet than it did in the file on my laptop!). Indeed, Münter was an admirer of the Dutchman’s work, even naming her home in the country ‘The Yellow House’, as a nod to his home in Arles.

The arms of the chair curve round and in before flaring out again, as if hugging the sitter. The right arm (seen on our left) is more brightly illuminated, and, as a result, appears to be a different colour (but with colour, everything is relative – see above). The left arm (on our right) reminds me of the roads you see in some Dutch landscape paintings, which start in the bottom corner of the painting, and lead you into the middle ground, as if the artist is expecting you to go on a journey with him (I don’t think there was a woman who painted landscapes in the Dutch Golden Age). I think the same is true here: Münter is using these arms, particular the one on our right, to lead our eye into the painting – and also, as the corners of the pyramidal composition.

I’m not an expert on women’s dress (nor on men’s, for that matter), but the blue top appears to continue as an open overskirt, framing the sleeker black skirt. Either that, or she is sitting on a blue cushion of the same hue as her blouse. Whatever it is, this blue, and the uncovered section of the seat of the chair, both form triangles pointing up towards Roslund’s face. Her left leg is crossed over her right – again, a confidence in her body language which we might not think of as ‘lady-like’ for the first half of the 20th Century. The black outlines to the blue blouse might relate to the clothing itself, or they may be the result of Münter’s interest in Bavarian folk art, particular reverse glass painting (painted on one side of the glass, to be seen from the other), which often had rich, jewel-like colours separated by black outlines, a cloisonné effect not unlike stained glass windows.

So who was this remarkable, stylish, self-confident, thoughtful woman? Well, a musician and author at the forefront of the Danish Avant Garde, but that is as far as I can get, I’m afraid. Münter met her while living in Copenhagen during the First World War. However, I can tell you that Anna Roslund had a sister called Nell, who was an artist, and who married a man called Herwath Walden in 1912. And it is this that made the portrait a key image for Making Modernism, one theme of which is the nature of artistic communities and the resulting dissemination of ideas. From 1910 Walden published a weekly journal dedicated to modern art (monthly from 1914-1924). It was called Der Sturm – ‘The Storm’ – the title expressing Walden’s conviction that that was how modern art was going to take Germany. His focus was on Cubism and Futurism (he effectively introduced these movements to the German public) and also on the burgeoning German Expressionist movement. In 1912, the year in which he and Nell Roslund married, they opened an art gallery in Berlin under the same name. Both Gabriele Münter and Marianne Werefkin, stars of Expressionists at Tate Modern, were exhibited regularly. Münter’s introduction to today’s sitter came via her gallerist, effectively. It might even have been this connection that took her to Copenhagen.

One question remains: if these artists were so successful when they were alive, why is their work so little known today? One reason, for the British at least – apart from the fact that the men they were associated with took all the limelight – is that there is very little of their work in public collections. This portrait is one of the few which was borrowed for Making Modernism from a British institution. It forms part of Leicester’s notable collection of German Expressionism, one of the rich seams of great art which, when you find them, are a surprising, but rewarding, feature of our regional museums. The same is true of Expressionists: one reason for Tate Modern’s thematic hang when it opened back in the year 2000 was that the first three decades of the 20th century are notoriously underrepresented, and in a chronological hang the first few rooms would be sparse indeed: just one early Kandinsky, and a scattering of Picassos. This current exhibition provides an ideal opportunity to get to know some truly great, truly influential artists – and to re-balance the view that it was the men who were coming up with all the ideas.