Oleksandr Bohomazov, Sharpening the Saws, 1927. National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kiev.

The Royal Academy’s exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s, about which I will be speaking this Monday, 12 August at 6pm, is undoubtedly one of the most visually exciting exhibitions I have seen for a long time. Relatively few of the artists who are included were known to me, and those who were, such as Kazymyr Malevych (Ukrainian, rather than Russian transcriptions are favoured throughout) and Sonia Delaunay, do not have the same impact as some of the brilliant artists who are, for me, discoveries, such as Vasyl Yermolov or Oleksandr Bohomasov, about whom I am writing today. The fact that the paintings have made it to the UK is a story in itself, and if you can’t make it to the talk on Monday I would urge you to get to the Royal Academy before the exhibition closes in October. The following week, on 19 August, I will return to Laura Cumming’s superb book Thunderclap, to think about at The ‘other’ artists – i.e. the ones she discusses who are not Carel Fabritius. To round off the talks in August, on the 26th I will look at the act of looking itself, alongside Piero della Francesca and David Hockney, by introducing the National Gallery’s Hockney and Piero: A Longer Look, which opened yesterday. After that things are still pretty much up in the air, but will probably include two talks looking at saints from medieval paintings in the National Gallery, an introduction to the NG’s forthcoming Vincent van Gogh exhibition, and a tour around ‘the Piero trail’ – thus returning to one of our heroes from the end of August, in anticipation of what looks like being a very ‘Renaissance’ autumn. But as soon as things are pinned down I will post details in the diary.

This painting was never meant to be seen on its own. It was originally supposed to be part of a triptych, a form which is otherwise unknown in modern Ukrainian (or for that matter, Russian) art. But for now I’d like to look at it as an object in and of itself. We can see three men performing various actions relating to the title of the painting, Sharpening the Saws – and, even if the definite article didn’t tell us that ‘the’ saws were the subject of the painting (rather than the men), the painting itself makes that clear. I can see six, painted in a variety of rich colours, and at two predominant angles: just off vertical and just off horizontal. Both of these features – colour and angle – are essential aspects of Bohomazov’s work. His major concern was how an artist could communicate with his audience, or, in other terms, what it was in a work of art which conveyed the feelings and sensations an artist experiences to the viewer. He wrote several theoretical texts about these concerns which seem to have anticipated the ideas – and art – of the likes of Kandinsky and Malevych, but even now they have been relatively little read (including, I confess, by me). In this painting, for example, both the colours and the angles of the saws help to convey the energy of the activity. Rhythm was another essential aspect of his work, something which he saw as not only quantitative but also qualitative, an element of art which could express concepts as diverse as speed, energy, regularity or mood: something which can be both measured and felt.

This detail shows the bottom left corner of the painting – which disguises the fact that the titular activity – sharpening – takes place at the exact centre of the canvas. A man in a fuchsia-coloured top and burgundy trousers is sitting on a section of a log with what appears to be a dark green saw resting across his lap. Holding a file in his two hands – the handle in his right, the working end in his left – he is sharpening one of the teeth of the saw about a fifth of the way along: the file is almost at the dead centre of the painting. Given that there are three other saws lying next to him, he clearly has his work cut out. These three saws – in deep blue, an even darker green, and cerise – splay out from a single focus. This is a technique which Bohomazov had developed in his earlier, more abstract works, and is one way in which he conveys movement. This can be read as energy either leading in to the focal point, or radiating out from it. Bohomazov’s prime interest could be rendered as ‘we see what we feel’, and the way you personally see this movement – in or out – is, I suspect, dependent on your own temperament. As well as having this rhythm of forms, there is also a rhythm of colours – blue, green and cerise – which helps to create the visual excitement of the painting, and reminds us that the saws are the subject: the colours are far more intense than those of the partial logs on which the man is sitting, and so they grab our attention. The saws are all tapered, with the broader end closer to us – the exception being the more vertical example held by the man in yellow on the left (we’ll come back to him later). The broader end has a thin bar attached to it, with a ring at the end, through which a small round pole, presumably made of wood, has been inserted. There is an unusual object in the bottom left, the same colour as the poles (so presumably also wood), the function of which is not immediately apparent (unless, perhaps, you are a sawyer). It is circular, with round poles projecting from opposite sides – similar to those on the end of the thin bars – and square protrusions at right-angles to the plane of the circle. There is also a black line describing the diameter of the circle.

The man standing on the left of the painting is checking that the process of sharpening is complete, looking along the saw to check that everything has been done correctly, and that each tooth is correctly aligned and suitably sharp. This is perhaps the most naturalistically coloured example, with the blade arguably a tempered yet slightly rusty steel. The harmonious way in which the men work with each other, and with their tools, seems to be expressed by the way in which the saw is aligned with this man’s left leg, on the same off-vertical diagonal. His weight is supported on his vertical right leg, almost like a classical contrapposto. This leg is the only significant vertical in the painting, suggesting that the man is clearly stable, in control, and, we can therefore assume, reliable. Lying on the ground behind his right foot is a log, a section of a tree trunk which has been cut transversely, but not yet longitudinally. Once the saws are sharpened and put to good use, this log will be turned into a series of rectangular beams, some of which we can see to the left of this standing man’s leg, stacked in an open, square formation to dry, or ‘season’, the lumber. Above this is an orange structure, presumably constructed from even more beams.

A similar orange structure forms an almost theatrical backdrop to the man in green with a yellow-green hat. The striations in this structure again suggest that it could be formed from a series of cut wooden beams, which admittedly look as if they are rather precariously stacked. One of the problems of interpretation is that, apart from the deep blue sky, the dark blue distant hills, the green grass, and some of the logs, colour is not used for its descriptive function, but for expression, differentiation, and – as ever, with Bohomazov – the creation of rhythm. The man in green smiles, and looks over to his colleague who is hard at work. He looks relaxed – which might imply that the work for the day is almost done. He holds a red-pink saw with a hand that looks slightly oversized – presumably gloved, given the way he wraps his hand around the teeth of the saw: even if it were blunt this wouldn’t be comfortable! On the far right there is a pink cloth draped over a pole – presumably a tent-like construction to store the wood, or the saws.

If we return to the centre of the action – the sharpening of the saws – but this time looking at the bottom right corner of the painting, certain things become clearer. For one thing, we can see the curious circular structure from the bottom left corner put to its proper use: it is at the thinner end of the cerise saw, the black line across the diameter being a slit into which the saw has been inserted. The two short, round poles are handles: the saw could therefore be held at either end, but, given how long it is, it would need two people to operate it. The man in green is sitting on one of several logs which have been sawn longitudinally – along the trunk – but have not yet been refined into rectangular beams. The different qualities of the wood and bark are expressed by different non-naturalistic colours – pale blue on the outside (the bark, effectively), a thin a layer of pink and a thicker one in pale green, and underneath a more-or-less naturalistic wood colour. These hues are less saturated than those used for the saws: while these sawn logs are relevant as part of the process, it is the saws, as ever, which are most important. This is insistently stated, even evoking the action of the saws. The angle between the green saw (being sharpened) and the blue one could be read as describing the sawing motion itself, back and forward, with the repeated regularity of this movement restated by the nearer green and cerise saws.

As a whole the painting is a paean to this process – from the trunk, cut into logs transversely, the logs cut longitudinally, then refined into beams, which are stacked openly to dry, and then, when fully seasoned, stacked more densely. The work has resulted in the blunting of the saws and the need for them to be sharpened. But, however complete this process may appear, it is not the whole story. As I said above, this painting was just one from a triptych, of which only one other was completed.

The central section, Sawyers at Work (1929), is also in the National Art Museum of Ukraine – but sadly, not in the exhibition (for historical reasons I suspect it is rather fragile). It shows the saws in action – being used just as supposed. The men standing atop the open platform hold the handles attached to the thin poles at the broader end of the saws, while the men on the ground hold those on the circular structures which are threaded over the thinner ends. The saws are operated vertically, or at a slight angle, as they make the long longitudinal cuts. As they work their way through each trunk, the trunk itself would also have to be moved, edged further out, or they would find themselves sawing through the supporting platform. Note how the most active man wears the deepest colour – a dark blue – and is about to thrust down the most richly coloured, red, saw. Meanwhile, a man in green (possibly the same one as in the other painting – he also wears a pale hat) sits on a completed beam at the top right. Maybe this contrast between action and rest, and the tones and hues used to portray it, could tell us about Bohomazov’s language of colour. And maybe one day I will read Bohomazov’s Painting and its Elements (1914) and find out.

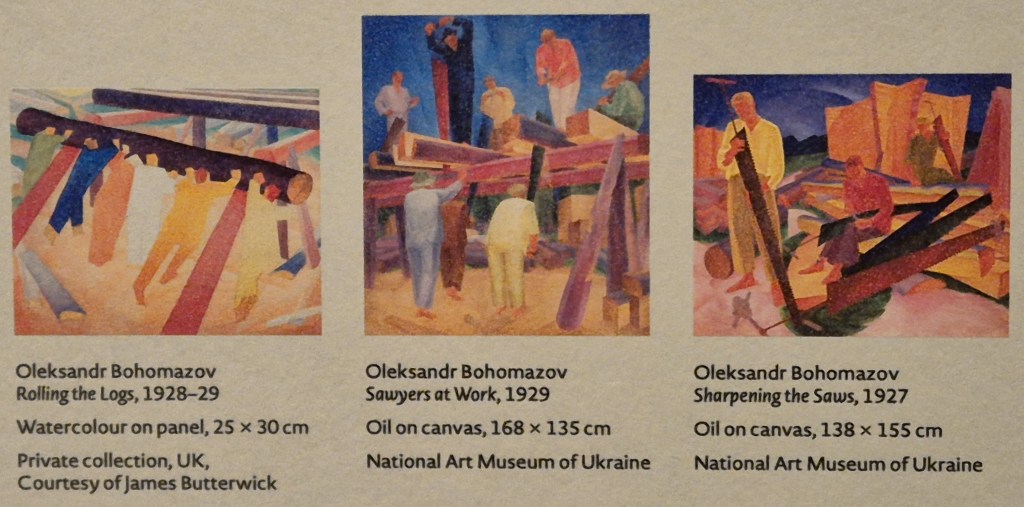

Sadly, as I have said, the triptych was not completed, although it had been fully planned. Among many other drawings and sketches, a watercolour study survives, which was sold relatively recently by James Butterwick, the leading dealer in Ukrainian art (and one of the Partners in the publication of the superb catalogue, £10 from the sale of which goes towards supporting museums in Ukraine). The watercolour has has been used in a reconstruction of the triptych in one of the interpretation panels at the Royal Academy.

When seen together we can see how the rhythms of the painting are all-important – with the dark diagonals formed by the logs in the left hand image leading from the top left down towards the central painting, in which the vertical action is paramount. On the right, the man in yellow frames the edge of the painting, with his saw leading us in, but also framing the man who is sharpening, who is ‘supported’ but the three saws on the right. At a lower level these echo the logs in the left hand painting, and lead our eye in from the right of the triptych towards the centre. The standing man’s saw in the right painting is reflected by the beams which support the platforms in the two other paintings. From left to right – or right to left – the rocking rhythms surely echo – once again – the act of sawing itself. This triptych was executed from right to left, and could equally well be read that way: all the elements of the process – and the art – work together.

Whichever way you read the triptych, the watercolour sketch Rolling the Logs (1928-29) shows what could be seen as the first stage in the process, with the unsawn logs being rolled up onto the wooden frame in preparation for work to begin. The logs are large, and extremely heavy, and six men work together to perform this task – the colours suggest that they could easily be six of the eight men in Sawyers at Work. If it hadn’t been obvious before, this act of collaboration could help our understanding of the overall meaning of the triptych: this is the work of a collective, with the citizens of the soviet working together. The irony of this is that, at the opposite end of the political spectrum, fasces – which give fascism its name – are bundles of sticks. A single stick can be broken easily, but as a bundle it is unbreakable. In both cases the group effort is seen as essential to the survival of the whole society. The problem with both systems is, I suppose, that individual rights get suppressed by the directives of the few in control. But let’s face it, I’m not a political theorist. Yet here we are, realising that art is not necessarily an escape from the everyday world (which, of course, it can be), but also an essential element in understanding who we are and how we live. It’s not the icing on the top – it is an expression of the whole thing.

But what were the politics of the artists themselves? There is, apparently, a lot of work still to be done on the motivation of Ukrainian artists at the time. Bohomazov’s work is some of the first you will see if you visit In the Eye of the Storm – but his early output is unrecognisable when placed alongside The Sharpening of the Saws. Many artists – and Kazymyr Malevych is the most famous example – changed their style from abstract, or at least highly stylised, to a more politically acceptable form of socialist realism, which is how we could describe Sharpening the Saws. However, it is not clear, for each individual artist, whether this was the result of obligation – effectively a pragmatic stratagem for survival – or genuine political conviction, or even inwardly motivated artistic development. Whichever it was for Bohomazov, it is chilling to think that, had he not died of TB in 1930, he may well have completed the Sawmill Triptych, but, even so, he would probably have died in the Stalinist purges of the 1930s, like many of his contemporaries. The fact that these paintings survived at all is effectively an accident of history – but more about that on Monday. And that fact that they have been brought to safety speaks of the dedication of some determined and courageous people who realised that this art – this witness to the power of the human spirit – should be seen more widely. For this reason, if none other – the brilliance of the art, for example – I cannot recommend the exhibition highly enough.

Thanks Richard for your flowing description of this amazing painting. I very much enjoyed it at the exhibition, but to realise that it is the centre of a triptych was very moving. And also to learn that the benighted painter died of TB…

LikeLike

Thank you, Lalage – a remarkable artist. I loved his early works in the exhibition, and I loved this… but I didn’t connect the two styles! The whole show is so vibrant, exciting and optimistic… and as a result, rather moving. Tragically parts of eastern Europe (Hungary, Slovakia…) seem to be going the same way now…

LikeLike

Dear Dr Stemp

Looking forward to your talk. Not yet visited the exhibition but will do soon. If your example is anything to go by, they look exciting, vibrant and vital.

Stephen Brooks

LikeLike

It is wonderful! I do hope you can get there – exciting, vibrant, and vital – profoundly optimistic… so also, in retrospect, rather moving.

LikeLike