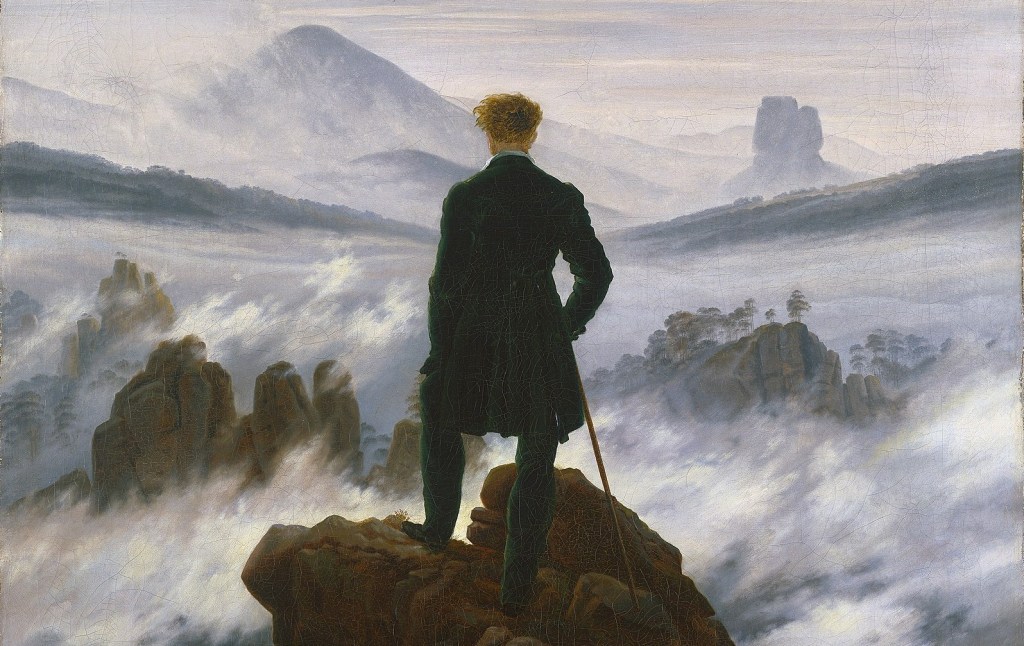

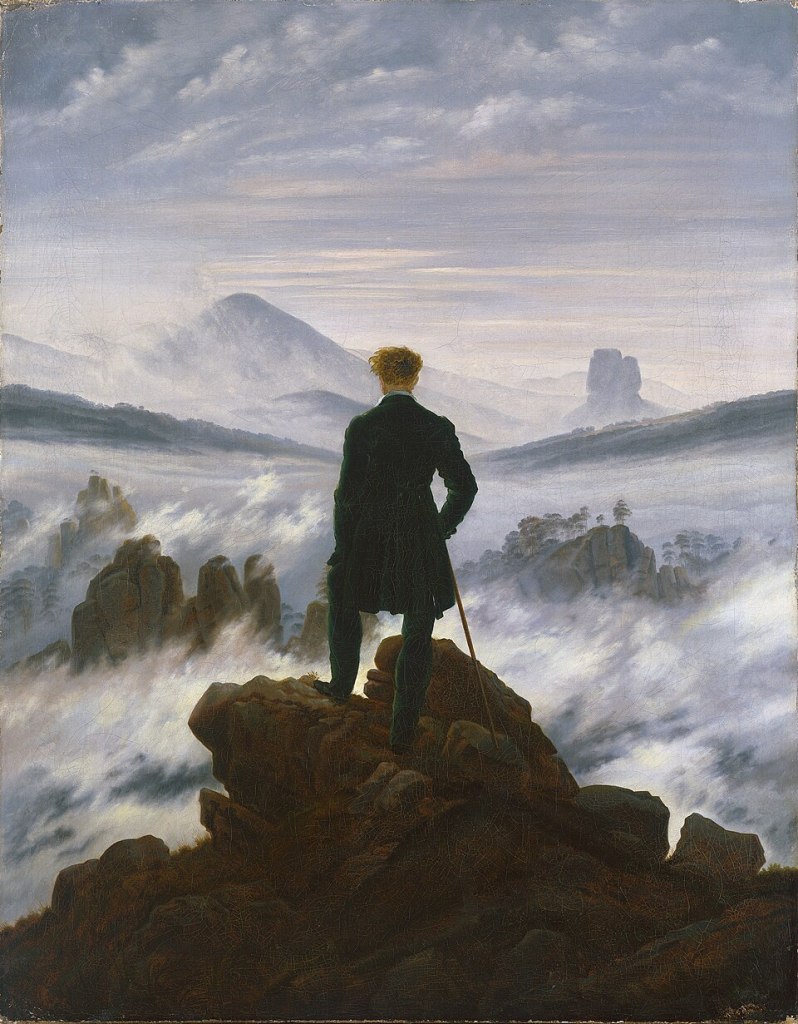

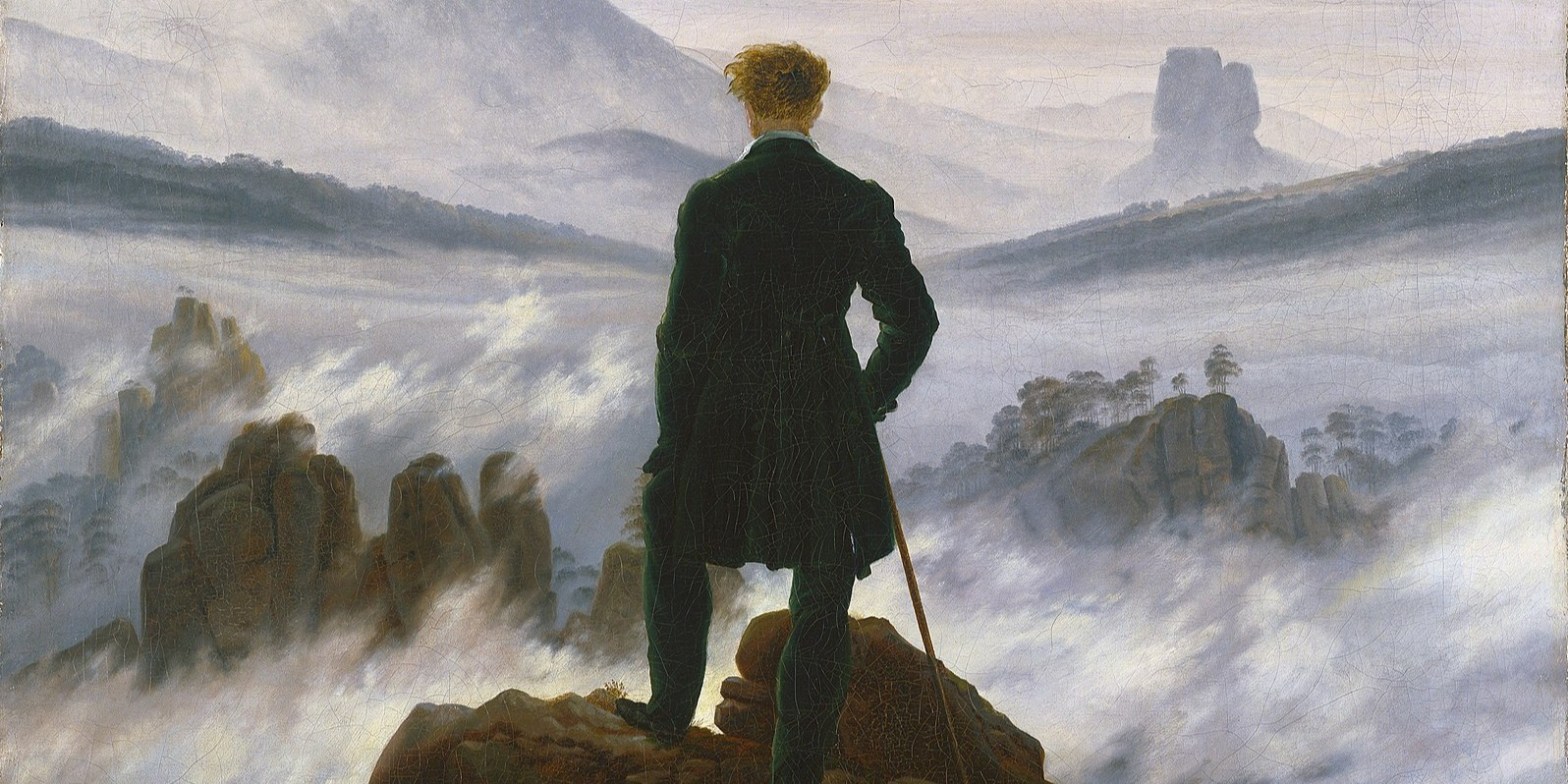

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, about 1817. Kunsthalle, Hamburg.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is one of the archetypal images of German Romanticism – so what better painting to look at as an introduction to my eponymous talk this Monday, 5 May at 6pm? To be honest, I’m not sure if I’ve ever seen it in real life, as the last time I was in Hamburg (December 2023) they had moved it into an exhibition looking forward to the 250th anniversary of the artist’s birth (1774), which unfortunately didn’t open until the week after we’d left… Since then, different embodiments of the show have been seen in Dresden and Berlin, and it is currently at the Met in New York, marking over a year of celebrations. The American incarnation closes on 11 May, in case you are stateside and on the East Coast: the first half of Monday’s talk will effectively walk us through it. However, I’m hoping that the Wanderer will be back on the walls of the Kunsthalle in Hamburg by the time I get there on 29 May – who knows if I’ll be lucky? As well as Friedrich, Monday’s talk will also look at the intriguing and idiosyncratic paintings of Otto Philipp Runge, an acquaintance and colleague of Friedrich, and another of the leading Romantic artists. I shall try and include others when appropriate. In the weeks that follow I will gradually work my way through German art history, looking at The Nazarenes (12 May), German Impressionism (19 May), and Ernst Barlach (26 May). All of these talks are now on sale, and you can either click on these links or look in the diary for more information. In the midst of it all I am heading to Paris for two days to catch the exhibitions Revoir Cimabue (‘A New Look at Cimabue’) at the Louvre and Artemisia: Héroïne de l’art at the Musée Jacquemart André. I am hoping to give lectures on both in June. Meanwhile… Germany.

This is undoubtedly one of Western Art’s ‘iconic’ paintings – the sort that is widely recognised, and often quoted. Maybe it’s not as familiar as the Mona Lisa, Munch’s The Scream, or ‘Whistler’s Mother’, but it is up there somewhere. Like all of them, there is a single figure forming a bold silhouette, so that the composition makes a strong, initial impact. This is easily remembered, and so can be instantly recognised: the boldness creates a sense of familiarity. This painting has the added bonus of mystery: who is this man? We would not recognise him even if we met, as he stands with his back it to us. We cannot see what he is thinking, or guess how he feels. He stands atop a rock formation looking out over the title’s ‘sea of fog’ (‘das Nebelmeer’ in the original German), and over the mountaintops which project from it. He wears a dark green, well-tailored coat, knee-length and gathered at the waist, with matching trousers. The rocks on which he stands are as dark, although brown, while the fog ranges from white to bluish-grey, with hints of lavender and pink, colours which are echoed in the sky.

These colours, and the shapes they form, help us interpret the painting, I think. I don’t know how much time you spend looking at the sky, or thinking about what you see, or even where it is, but if you look directly upwards, you are looking at the part of the sky that is closest to you. The sky above the horizon, or just touching it, is furthest way. I know this is obvious, but it’s worth considering, and I suspect it is not something we often register explicitly. When painted, the sky acts as a sort of external ‘ceiling’, directly above an equivalent, perspectival floor, so that, at the top of the painting, the sky is in the foreground, and the lower down the painting it goes, the further away that section of the sky is: where it meets the horizon the sky is in the background. This is still really obvious, I know, but it’s worth clarifying. In this detail, which shows all of the sky above the distant mountains, the clouds at the top are turbulent, with puffs of strongly contrasted light and dark, whereas those below are calmer, with stable, horizontal streaks of similar, close-hued, light tones. This implies that the weather nearby is rougher than that in the distance. If we are travelling in that direction – as the gaze of the ‘Wanderer’ suggests – things are going to get better: we are looking towards the calm on the horizon, both visually and metaphorically.

However, it is not entirely clear where the Wanderer is standing: on top of some rocks, yes, but not quite at the very top. And we don’t really know where these rocks are. Placed against a backdrop of fog, and with other rocky peaks which seem to be lower, we inevitably assume that he is at the top of a mountain. However, as we see these rocks out of context, we have no way of telling how broad, or high, this mountain is, nor how close he is to any vegetation… or for that matter, civilisation. He seems to be alone in the world, and potentially on the edge of a precipice. Nevertheless, these rocks do create that archetypal artistic construction – a pyramid – and he is placed on top of it, the focus of the composition. His left foot is higher and placed at an angle. His right foot points directly into the painting, stable at the end of a straight, supporting leg. The left leg is bent. I have no doubt that he is poised, stationary, to contemplate the view – he has a walking stick which projects to the right, helping to create visual, as well as physical, stability. Nevertheless, there is still the possibility that he could straighten that bent left leg and take a step forward with his right, either onto the higher stone, or even over the brow of this particular peak. Is he content to reach this summit, or will he head on to the mountains in the distance?

To the left, the rocky peaks are broad, and rounded, and, like the foreground where he is standing, they are devoid of vegetation. To the right, a larger mass of stone is topped with trees, but trees which, thanks to their distance, appear quite tiny: each would easily fit, pictorially, into the gap formed by crook of his arm. But has Friedrich got the perspective ‘right’? The trees seem too small, making that distant outcrop seem even further away than the shapes made by the fog would suggest. Of course, there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ about it: the artist is using our understanding of perspective to show us the size and scale of the world around us: the world is enormous, and we are tiny in comparison. The painting is an example of the ‘Sublime’ which, in philosophical terms, represents a greatness beyond all possibility of calculation, measurement, or imitation. It can be exciting, or terrifying, or even both. For observers of a painting it works particularly well, though, because we know that, how ever large and potentially dangerous the world is, we, at this moment, are safe in the comfort of our own home.

Having said that, this man does not appear to be ‘tiny’ in comparison to the world. By making the rocks on which he stands equivalent to those in the distance, and by showing him as so much larger than the trees, this man is made truly monumental – heroic, even. Indeed, he is the very essence of the Romantic hero. His head is of the same order of size – on the picture surface – as the rock formation to the right. This is actually a fairly accurate depiction of the Zirkelstein, a table mountain which overlooks the River Elbe about 50km South East of Dresden, where Friedrich lived and worked. I can’t help thinking that the mountain has a head and shoulders not unlike the ‘Wanderer’. He is part of nature, and yet separate from it – another essential Romantic idea. Nature seems to converge on him. Notice how, just below the Zirkelstein, the top of a long, gently-sloping hill emerges from the clouds, and leads down in a shallow diagonal from the right edge of the painting to the Wanderer’s right arm. Another hilltop leads down in a similar shallow diagonal from the left to his left arm. There are mountains visible on either side of the flared skirts of his coat, and, as we saw above, he stands on top of a pyramid of rocks – which could in themselves be the tip of a far larger mountain.

Our eye level should be where we see the horizon, which suggests that the distant mountain is higher than his current position: it looms above his head. The slopes are apparently less rocky, and we might assume that it would be relatively easy to climb – an uphill walk, maybe, arduous, given the scale, but not a scramble. Some people think this is either the Rosenberg, or the Kaltenberg, but I’m not sure that either has exactly the right profile – but again, that is immaterial. Friedrich went out into the countryside, made sketches, and later rearranged them and altered them according to what would work in the painting – ‘pictorial necessity’. Here it is notable that the right slope of this mountain leads down behind the man’s face: he is looking at this very slope, and the hills beyond.

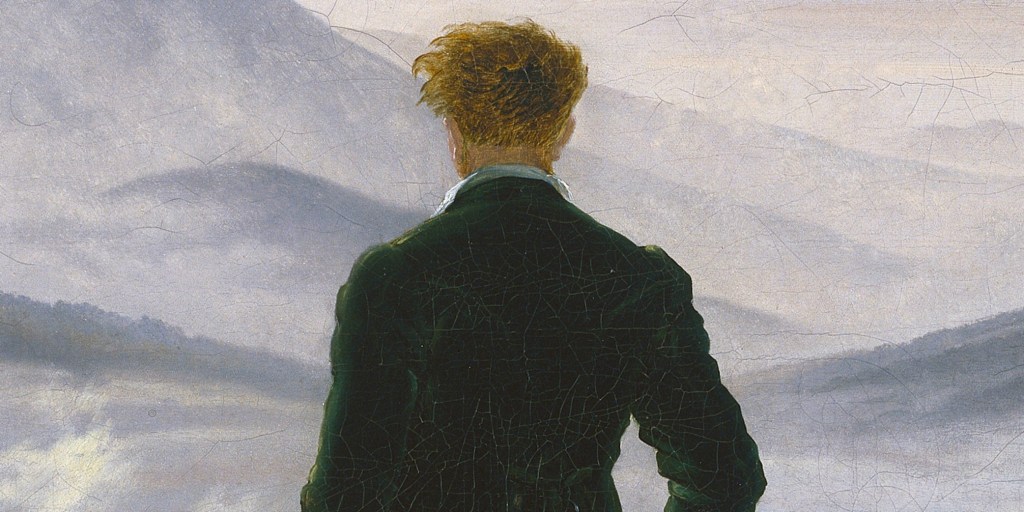

However bold the composition as a whole, the details are remarkably delicate. Notice how the light catches his shirt collar on the left, and to a lesser extent, also on the right. If you look closely enough, you can also see that it glances over the outline of his left ear. His ginger hair blows in tufts in the breeze. Caspar David Friedrich had red hair, by the way. This could be him.

But what does it all add up to? Everything focusses on the Wanderer: the rocks in the foreground support him, the apex of a pyramid, and mountains frame him to the left and right. The tops of the hills slope down towards him on either side – as if pointing towards him – and a distant mountain even resembles him. He is also exactly in the middle of the painting, his body lined up with the central vertical axis. We are looking directly at him, and yet we cannot see his face. However, by painting him from behind – what the Germans would call a Rückenfigur (literally, ‘back-figure’) – we are invited to look at what he is seeing, the ultimate repoussoir. We are looking at the act of looking, and the implication is that we consider not only what we can see, but also, how that would make us feel. This is the very essence of Romanticism: a personal response to the world around us. The movement grew as a reaction against the Enlightenment, during which the world was explored, measured, evaluated and rationalised. Romanticism invites a more emotional response. Friedrich is not documenting a precise geographical location, telling us physically where he stands, but is provoking us into a metaphorical consideration: how do we feel about our place in the universe? However, he doesn’t tell us how to feel. As a result, the interpretations of this painting are many and varied. It has been suggested that Friedrich’s concerns were political – relating to German Nationalism, as a response to the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, just two years before the painting was begun. Ironically, by occupying many of the small independent states that made up the fragmented political landscape of Germany, Napoleon’s actions provoked a greater sense of what it meant to be German. He therefore helped to promote unification (the same was true in Italy). Alternatively, the painting could be a religious statement, expressing awe at the majesty of God’s creation, with the rocks as a symbol of a secure Faith, standing strong and reaching to the firmament. Friedrich profoundly believed in God’s presence in nature, as we shall see on Monday. Or it could be a meditation on his own journey through life. Every peak of achievement can turn out to be the brink of a precipice. And even if that’s not the case, how can we ever know if we have reached the ‘top’? How many more mountains must we climb – metaphorically – before we can find the peace promised by the calmer skies and gentler slopes on the horizon? As far as Friedrich’s own life is concerned, is it a coincidence that not long after he began this painting he would get married?

However we see the painting, the formalised composition implies that there should be a metaphorical interpretation. The sense of life’s journey, and the Romantic notion of an individual’s response to the situation in which they find themselves, is expressed explicitly through the notion of the Wanderer himself, and the very idea of Wandering. You only have to remember what William Wordsworth was doing in the opening line of what is surely most famous poem by one of Britain’s most famous Romantic poets: ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud…’. Wandering – and the discoveries which result – is essentially Romantic. However, for Caspar David Friedrich – judging by this painting, if nothing else – clouds were anything but lonely.

Do you actually really want to talk about David Casper Friederich if you have not seen the painting ? I have seen it, in Hamburg a few years ago, he was and remains one of my most favourite artists.

LikeLike

Hi Barbara,

I’m so sorry, but I’m not entirely sure what the point of your question is. Do I actually really want to talk about Caspar David Friedrich if I haven’t seen the painting? Well, yes, I do, and yes I have. And would you have known I hadn’t seen it, if I hadn’t said so in the first paragraph? I am so glad to hear, though, that he is one of your most favourite artists. Nevertheless, for future reference, his name is Caspar David Friedrich, not David Casper Friedrich. Caspar was his first given name, and is spelt with two ‘a’s.

LikeLike

RichardBrilliant article..about a painting I gave seen ( not

LikeLike

Might you also have time in Paris for super Susanne Valadon exhibition at Centre Pompidou? Would love to hear you thoughts on her work on a Monday evening talk

LikeLike

Dear Ruth,

What a great idea! I would love to see the Valadon, but then I’d also like to see the Hockney, and the Degenerate Art at the Picasso Museum, which I think are still on. But I won’t even get to Notre Dame which I haven’t seen since it reopened… I arrive more or less in time to see Artemisia, and then am only there for one night. I’ll go to the Louvre the next morning to see the Cimabue, and spend the rest of my time in the Louvre, then back that afternoon, and up to Merseyside the following day. So apologies…

LikeLike

Dommage! R

LikeLike

Many thanks for your gre

LikeLike

A great pleasure!

LikeLike