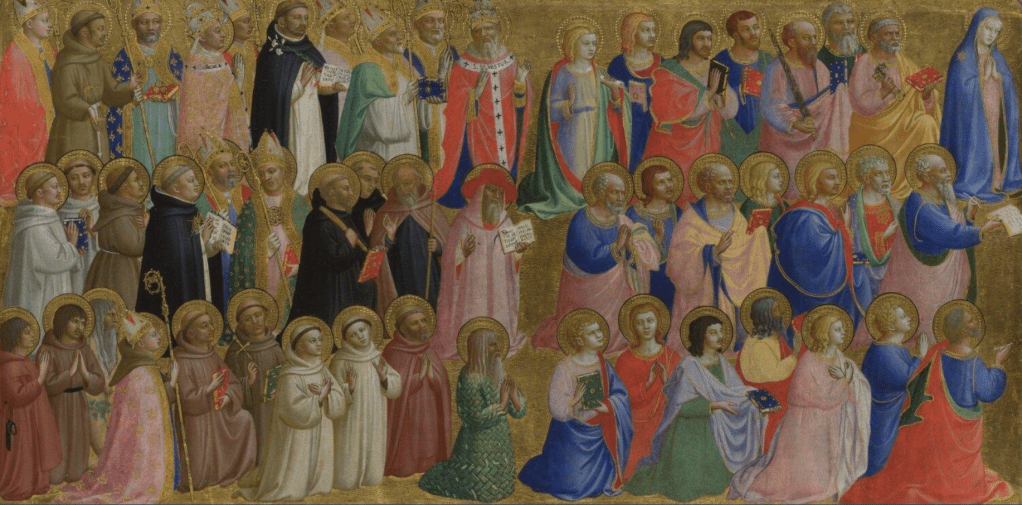

Fra Angelico, The Virgin Mary with the Apostles and Other Saints, about 1423-4. The National Gallery, London.

Greetings from Florence! I’m currently in the middle of introducing a second group to the delights of the first half of the 15th century, with a rich array of works related to the career of Guido di Pietro, who we now know as Fra Angelico. The day before I left home I talked about the earliest works in his career (as currently exhibited at the exhibition Fra Angelico in San Marco), and on Monday 20 October (the day after I get back) I will explore the superb range of paintings spanning the rest of his life As seen at Palazzo Strozzi. We will return to the convent to think about Fra Angelico: At Home in San Marco on 27 October, exploring the frescoes he painted for the friars’ cells, and for the communal areas of the building, as well as a selection of manuscripts he made for the Dominican order. My last talk in this series (3 November) will introduce some of his Students and Successors, as well as discovering what remains of the artist’s work after he left Florence. We will also explore the ‘School of San Marco’: painters including Fra Bartolomeo, Fra Paolino and Plautilla Nelli – the first woman recognised as having a successful career as an artist in Florence – who were the most important Dominican artists of their day.

Subsequent talks will cover two exhibitions from the National Gallery, Radical Harmony on 17 November and Wright of Derby: Out of the Shadows on 24 November, and they will go on sale soon. In December I will probably be talking about Vermeer at Kenwood, the Barber Institute at the Courtauld, and Constable and Turner at Tate… Details will be in the diary before too long!

As a reminder, this is the predella of Fra Angelico’s first major altarpiece, originally painted for the high altar of San Domenico in Fiesole, the priory he joined sometime between 1418 and 1423. The convent (a term which can refer to the homes of either nuns or friars) remained his ‘House’ for the rest of his life, despite the widespread assumption that he moved to San Marco in Florence when the Dominicans took over that building in 1436. The church of San Domenico developed over the centuries, and the altarpiece was adapted by Lorenzo di Credi in 1501, changing it from a polyptych to a single-panelled pala. At some point in the 19th century the predella was removed from the convent, ending up in the hands of a dealer, and later, in 1860, it was acquired by the National Gallery. I talked about the central panel two weeks ago, so this week I will turn to the panel which has the next highest status – at Jesus’s right hand (or, from our point of view, to the left of centre).

Similarly to the way in which the angels are arranged in the central panel, there are three rows of figures in brightly coloured clothing. However, as you look from right to left (and so away from the centre of the altarpiece) there is a gradual decrease in colour, with more neutral hues and monochrome costumes. This is related to the decreasing status of the subjects the further away from the centre they are and, more specifically, who they are and why they wear those clothes. Even on this scale it is possible to see that all of the figures have circular gold haloes, and so they must all be saints. What you might not be able to see is that the haloes of the bottom two rows are ringed with black paint, just like the angels in the central panel, whereas those in the top row are not. However, you should be able to see that here.

Starting closest to the centre (on our right), no figure is closer to Jesus than the woman at the top right. Kneeling in prayer – as all the figures are – she wears a long blue cloak which also covers her head. This cloak has an olive green lining, and is trimmed with a gold hem. Her dress is pink. On her shoulder we see a star, derived in part from the medieval canticle Ave Maris Stella – ‘Hail, Star of the Sea’. In it, she is compared to the Pole Star, which sailors use to navigate, the implication being that we should use her example as our guide in life. The Latin for ‘of the Sea’ – Maris – was also a pun on her name: Mary. All Catholics are supposed to have a special devotion to the Virgin Mary, but for Dominicans she has a particular significance. In his superb book, Fra Angelico at San Marco, William Hood compares each convent to a beehive, and, ‘…like a honeybee every friar had his place in the collective at whose heart was the Virgin Mary, the legal abbess of every Dominican convent, or by extending the metaphor one could even say its queen’. It is perhaps for this reason that Mary is seen not only closest to Jesus in the predella, but also separated from everybody else. Just below her is St John the Evangelist in his older embodiment as the author of the gospel, rather than being shown as the youngest of the apostles. His quill is held, rather curiously, in his left hand: I can only assume that this is for purely aesthetic reasons. But then, he is using his right hand to offer his gospel to Jesus, which might explain also explain it: holding the bible in his right hand might be seen as more suitable (everyone trustworthy was assumed to be right-handed, especially given that the Latin for ‘left’ is sinister). John’s arm is clad in the same rich blue worn by Mary, and this colouristic similarity creates an affinity between them – as does his pink cloak lined with green, colours which are also used for the Virgin’s clothing. Bizarrely, the open page of his bible is illegible, made up of scrawled lines, whereas elsewhere on the panel there is writing which can be read – but perhaps that is because the first verse of St John’s gospel is so well known ‘In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God’. His gesture is therefore important: the bible – the Word of God – is here being held towards Jesus – the Word of God…

The remainder of the figures in this detail (I’ve repeated the same one), have been identified as ‘apostles’, but that creates a bit of a problem. We ‘know’ there were twelve of them, but here there are fourteen. Even after Judas’s suicide there were twelve: the community gathered together to appoint a replacement, St Matthias (see Acts 1:15-26). Nevertheless, St Paul is often represented as one of the number, because, together with St Peter, he was seen as one of the first heads of the Church after Christ. Indeed, he is depicted in this panel. Just to our left of Mary there is a figure with short grey hair and a short grey beard carrying a pair of keys. These are the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven which Jesus said he would give to St Peter. Now, St Peter very often wears yellow and blue, but here he has yellow and pink. There is a real sense that Fra Angelico wanted Mary to stand out, and if Peter was also wearing blue that might not happen. However, given that he is wearing pink he is more closely associated with the man to our left of him, who has a longer, darker beard and a receding hairline. He carries a sword, which, like one of Peter’s keys, is picked out in silver leaf: this is St Paul. Consequently, the first two heads of the Church are in the top row, and are more-or-less the closest to Jesus after Mary. It’s only ‘more-or-less’ because there is another figure squeezed between Peter and Paul. He has white hair and a long white beard, and is wearing green – which is the most common way in which Italians represent St Andrew, the brother of St Peter. However, as yet we haven’t sorted out who all these people are. If we have St Paul and St Matthias numbered among the apostles, that would still only bring us up to thirteen. So – who is the fourteenth? This is what it says in Acts 14:13-14

Then the priest of Jupiter, which was before their city, brought oxen and garlands unto the gates, and would have done sacrifice with the people.

Which when the apostles Barnabas and Paul heard of, they rent their clothes, and ran in among the people…

So Barnabas – who travelled widely with St Paul and is mentioned more often that Matthias – also appears to be counted as one of the twelve. It’s clear, though, that the role of ‘apostle’ is not strictly limited to the number originally chosen by Jesus. Nevertheless, if we include Barnabas together with Matthias and Paul we have arrived at fourteen. However, although St Paul is clearly distinguishable, the others are not. Have a look, though, at one of the figures who stands out in the lower row in the detail above. He wears a cangiante pink and yellow cloak (see the previous post for an explanation), which in itself makes him more prominent. He also seems to take up a bit more space than anyone else in this row, with one elbow sticking out to our left, and the book held up to our right. Now compare him to the figure standing in the position of honour – at the right hand of the throne (i.e. on our left) – in the Fiesole Altarpiece. This part of the predella would have been directly below this Saint.

It is surely no coincidence that both have short grey curly hair and beard, and have a receding hairline. They wear cloaks which are mainly pink, but also include yellow, and their other clothes are blue. Both figures are carrying a red book. It is also no coincidence that the figure in the main panel is St Barnabas. He occupies the position of honour as he is the patron saint of the donor, Barnaba degli Agli, who died in 1418, twelve years after the convent had been founded. It took a long time to finish the building – partly, no doubt, because the Dominicans have a vow of poverty, and had run out of money. In his will Barnaba ‘left 6000 florins towards the completion of the church, as well as liturgical furnishings and chalices’ (quoting from Dillian Gordon’s superb catalogue entry, to which I am also indebted for many of the identifications below). This sum covered not only the completion of the church (which was consecrated in 1435) but also twenty cells for the friars.

It would be all but impossible to name all fourteen of the figures in the detail above, although that hasn’t stopped people trying. St John the Evangelist and St Matthew were both apostles and evangelists, and it is possible that St Matthew is the figure holding a quill to our left of St Barnabas. But then, St Barnabas has a quill as well, and he didn’t write any of the bible. Admittedly there is an apocryphal Epistle of St Barnabas, but no one after the fifth century or so seems to have considered it relevant.

There are even fewer certainties about the members of the group at the bottom right, although it may include the remaining two evangelists, Sts Mark and Luke. Three figures hold a book, and one, on the far right, a quill, so these attributes wouldn’t appear to help. However, it has been suggested that the saint at the bottom right is St Luke. He is closest to Jesus in this row, and as the patron saint of artists, he might have been granted a higher status by one of his own trade. Luke does often (but not always) wear red and blue.

The top row on the left of the panel has some figures who are more easy to recognise. Going from right to left (and so, theoretically, in decreasing order of importance) we can see St Silvester, an early pope, who can be identified quite simply because his name is painted across the white strip on his robes. Behind him are three bishop saints, each wearing a mitre – St Hilary, Bishop of Poitier (with his name on his blue cope), St Martin of Tours (the name is on his book), and another, who remains unidentified. If you can’t see the writing – or any of the other details – look up the panel on the National Gallery website and zoom in! The next figure stands out because he wears the black cappa and white tunic of the Dominican order. He is also wearing the white scapular, which hangs across the chest and down below the waist, although here the end is out of site, hidden behind the saints below. This is the founder of the order, St Dominic himself. The lily is a sign of his purity, while the star in his halo denotes his unquestioned sanctity. The book is open at a paraphrase of Psalm 37:30, ‘The mouth of the righteous speaketh wisdom, and his tongue talketh of judgement’ – which could be taken as expressing the Dominican mission to suppress heresy though preaching, their wisdom founded on a profound study of orthodox beliefs. Next to him is another unidentified bishop, and then St Gregory the Great. He was a pope – hence his ‘hat’, the triple tiara – and was considered to have been especially inspired by the Holy Spirit. Indeed, if you can see a small white blob on his halo in front of his forehead, it is a tiny representation of a dove speaking into his ear. Next to him is another bishop wearing a deep blue cope covered in what I would have assumed were fleur-de-lis – which might have led me to assume that this is St Louis of Toulouse. However, he doesn’t have a Franciscan habit under his cope. Instead, there are three golden balls resting on his bible: it is St Nicholas of Bari (aka Father Christmas – the gold is for giving). The saint to our left of him is wearing a Franciscan habit (brown, with a rope belt) quite simply because this is St Francis – he is holding his hands out to show the stigmata. The row is completed by (yet another) unidentified bishop.

In the middle row, again going from right to left, we can see St Jerome, in his red cardinal’s hat and, unusually, a pink robe, then St Anthony Abbot, with beard and staff. There are two Benedictines in black, one with a stick, St Benedict, and another, who might be one of his followers, St Maurus. The two bishops could be St Augustine and St Zenobius (one of the patrons of Florence), and then another Dominican. Slightly plump, with a star at his chest and a book, this is the great theologian Thomas Aquinas. Another Franciscan is followed by two monks in white. I realise I am in danger of merely listing, and it really is worthwhile looking closely at the details – so here is St Paul the Hermit, wearing something that looks surprisingly like a basket.

St Paul was said to be the first ever Christian hermit, living in the Egyptian desert for 97 years – dying at the age of 113. He lived near a spring of clear water, next to which grew a palm tree which provided not only his food, but also all the materials he needed for clothing – and the detail is fantastic. Look at the care with which every strand of the woven palm leaves is depicted – the frayed ends, the veins, the variations of light and shade, and even the projecting fronds at his right wrist, everything seems so delicately painted, and the figure can only be around ten centimetres high. Now have another look at the predella as a whole (either at the top or bottom of this post), and think about the level of detail which Fra Angelico has included in almost every figure, and you’ll realise that this painting is truly remarkable.

I think it’s rather charming that, as the first hermit, St Paul is shown suitably isolated. Behind him a monk in brown is followed by two Carmelites in white, and then St Giovanni Gualberto, founder of the Vallombrosan Order, with one of his companions. Usually they wear a greyish brown habit, often darker than this, and with far fuller sleeves, but here they really doesn’t look that different from the Franciscans – although there’s no rope belt. Next to them is a bishop saint with a Franciscan habit under his cope – so this is St Louis of Toulouse. The last three are St Onophrius, a hermit who wore nothing but leaves, and two other unidentified monastic figures.

There are several things I find remarkable about all of this. The first is that, although we can’t identify every figure now, Fra Angelico would have known who every single one was. The second is that he could characterise them all, and had designed every single figure – even though there must be a considerable contribution from the workshop. Having said that, the panel is too small for more than one person to be working on it at any one time – but the master could have handed it over to his assistants when he had done the most important parts. The next is that this is just one of five panels from the predella, which would have been on the high altar out of reach of everyone except the officiating Dominicans. Even then, how could they have stopped to look at the whole company of heaven during Mass? Or would they have returned later, individually, for prayer and contemplation, gradually working their way through, naming every figure and addressing a different, appropriate prayer to each individual saint? Or is this painting ‘simply’ an act of devotion, painting each figure to illustrate the respect due to them, even if no one subsequently bothered to address them individually? Or – and this may make more sense – is the fact that we know that the artist knew who they all were enough? This would mean that we know that they are all identified saints, which adds to our understanding of the power of Christianity, given that so many recognised figures witnessed their faith, and died in that faith (the saints who are called ‘confessors’) or died for that faith (the martyrs)? We don’t need to know who they all are, we just need to know that somebody did, and that there are so many of them. And remember, so far we have only seen two of the five panels of this astonishing predella. What we find in the remaining three is in some ways more surprising. But then, the remarkable richness of Fra Angelico’s work is surprising, and that is one of the things we will think about on Monday.

I also wonder who, other than someone steeped in theological knowledge, could have painted so many saints with their individual distinguishing characteristics. Are there examples of “secular” painters doing the same without, perhaps, input from the religious advisor for the commission?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a good point, and one that I will try and answer in the next post… Any artist, whether a member of a religious order, or a ‘layman’, would have received advice from the patron – or the patron’s advisors – and often that would have included a learned member of the community for which the work was produced, whether religious or not. All works of art were effectively collaborations between the person who knew what they wanted, or had an advisor to tell them what would be best, and the artist themselves whose job it was to realise that vision.

LikeLike