Johannes Vermeer, The Love Letter, about 1669-70. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

My next two talks are dedicated to single works by two artists who had a lot in common – and yet were completely different: Vermeer and Caravaggio. They both worked in the 17th century painting religious subject matter and genre scenes, and both produced relatively few works. They died young, and were all but forgotten soon after their early deaths, only to be rediscovered in the 19th and 20th centuries, reaching an unparalleled level of popularity in the 21st. As a result, every painting by them is fascinating – and the arrival in London of even a single work associated with either of these masters is something to be celebrated. This Monday, 1 December (how is it December already?) we will start with Seeing Double: Vermeer at Kenwood. We will explore the Guitar Player in depth, taking it as a stepping-off point for a consideration of Vermeer’s career as a whole, and compare it to a remarkably similar, although by no means identical painting which is on loan to Kenwood House from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Two weeks later, on 15 December, I will turn my attention to Caravaggio, as his remarkable Victorious Cupid will be on display at the Wallace Collection: it has never been shown in public in the UK before.

The New Year kicks off with talks introducing two Tate exhibitions, Turner & Constable at Tate Britain on 5 January and the following week (12 January), Theatre Picasso at Tate Modern. After that my sights will be set on Scandinavia, with the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s exploration of the richly coloured paintings of Danish artist Anna Ancher. At the moment I have this planned for 26 January. Just before then I’ll be heading to Hamburg to see an exhibition of the great Swedish artist, Anders Zorn. Despite giving a couple of talks about his work around five years ago, and a few visits to Stockholm, I’ve seen very few of his paintings – so I can’t wait! He was a contemporary of, and equivalent to, John Singer Sargent and Joaquín Sorolla. Like them, his works are highly painterly, with full, lush brushstrokes, and, like Anna Ancher, his paintings are vibrantly coloured with a richness that contradicts the dark and brooding notion of ‘Scandi Noir’. That talk should be on 2 February, but I’ll post more details in the diary in the New Year… if not before. Today, though, I want to look at a painting by Vermeer which has some features in common with Kenwood’s The Guitar Player. Music is one of its themes, and yet it goes by the name of The Love Letter.

Vermeer manages to give us the impression that we have stumbled on something we should not see. We’ve arrived at a doorway to witness a scene which appears to invert the standard social order – a maid lording it over her mistress. Not only that, but neither has been doing what they should, judging by the appearance of the outer room – dark, dirty and messy – not to mention the inner room, which may be well appointed, but is nevertheless showing signs of neglect.

A curtain has been drawing back – and maybe it shouldn’t have been. There is a real sense of theatrical revelation though, a bit like someone sharing the gossip: ‘look what I’ve just seen…’. It is a curtain that very probably belonged to Vermeer, and he used it in other paintings, notably The Art of Painting. It’s also worthwhile remembering that some paintings were covered by curtains on rails – in part, to keep the dust off them – and sometimes artists even painted trompe l’oeil curtains to make what was being revealed appear more real, and to remind you that it was a valuable work of art by an esteemed artist. The curtain also has a classical reference, but I won’t go into that now. In this case, Vermeer is playing with both ideas – what is being revealed in the back room, and the suggestion that this is a painting that is worth looking after. On the left wall of the entrance hall – or whatever the room is – there is a map, a reference to the world outside this house. Vermeer may well have owned several maps (although I can’t see any in the inventory of his belongings), but he could equally well have borrowed them, choosing them sometimes for their significance, and sometimes, simply for their appearance. Here, I think it is a reminder that we are coming into the story from ‘elsewhere’, but also that whatever is going on in these rooms is in some way connected to the world outside this house – which is where the letter that the lady is holding must have come from.

Although drawing back the curtain has revealed the inner room, the lower half of the painting is, in some ways, more revealing. For one thing, our point of view becomes apparent. On the right is a chair, upholstered in red velvet with gold trims. It is facing directly towards us, so that the front of the seat is parallel with the bottom of the painting. Our view is cut off just below the tassels along the front of the chair. The bottom of the painting probably coincides with the threshold of the adjacent room. This implies that our viewpoint is relatively high, with our supposed eye-level demonstrated by the perspective. The bottom edge of the map, and the diagonals of the diamond floor tiles, create orthogonals which continue to the vanishing point of the painting, just above and to the right of the brass ball on the chair back. Looking at the bottom of the map, though, what is most striking is the state of the wall – dark muddy drips staining the light paintwork. This is the only painting by Vermeer that I can think of in which something is actually dirty – and this is just one of the signs of neglect. The messy, crumpled paper on the chair itself, and the objects in the doorway, are others.

A broom leans against a wall behind the door, and two slippers are left on the floor. Between them they take up the full width of the doorway. They are not in their proper place, and nor are they put to their proper use. The household chores – and the management of the household – are apparently being neglected. The maid would be responsible for the former, and the lady of the house the latter. Maybe the lady of the house has other things on her mind… Not only that, but once you get close enough you can see that the crumpled paper on the chair is actually sheet music. Even though what is written makes no sense, musically speaking (Vermeer seems not to have been worried about that), the implication is that the harmony created by well-played music has been set aside. This might have a bearing on the state of the household: there may be discord, and disorder.

Having negotiated these obstacles to get into the room, we are in the presence of a finely dressed lady and a maid – presumably her maid. The difference in status is marked by their clothing. Whereas the lady wears a yellow satin jacket trimmed with broad bands of fur, as well as a pearl necklace and earrings, the maid has a plain brown top over a chemise, plain blue skirts, and no jewellery. However, the maid stands over her mistress, dominating her. Not only that, but her left arm is ‘akimbo’ – a pose almost always adopted in 17th century Dutch portraits by men rather than women (although there are a few exceptions). You could see this as an equivalent of contemporary ‘manspreading’, allowing the men to take up more space and so look more important. Not only that, but the maid’s headdress is quite tall, and catches the light brilliantly, thus enhancing her importance within our visual field. Nevertheless, there seems to be a good relationship between the two. We do not know what has happened – and that is one of the great strengths of Vermeer’s art. He gives us so much of the evidence we need to work out what is going on, but not everything: we can tell our own stories through his paintings, and they can all be different. The lady is holding a letter, which appears to be unopened. She looks round, and up, towards her maid – who has presumably given it to her (although we have no way of proving that she has) – and the maid looks back, her face slightly lowered, with the hint of a smile. The lady is clearly concerned, the maid, somewhat amused. Her stance is down to earth, matter of fact, though: whatever the contents of the letter (and how could she know?), it clearly isn’t going to affect her that much. However, the two are pictorially bound together. Quite apart from the fact that they are perfectly framed by the door, the top of the maid’s white apron, which we see above the blue overskirt which has been hitched up, continues along the line of the white fur trim of the lady’s jacket, tying them together visually. The upper edge of the brown sleeve on the maid’s left arm also leads to the top of the lady’s head, and the inside of the crook of her elbow is level with the top of the gilded leather panel we can see through her arm. Both coincide with the lady’s right eye: everything in Vermeer’s compositions was always very precisely planned, and extremely specific. Notice the placement of his signature at the bottom left of the detail above, for example – not stuck away in a corner at all, but conveniently close to the action.

Given the title the painting has now, how do we know it is a love letter that the lady is holding? The musical instrument is one of the clues – as is the crumpled music we have already seen.

It is a cittern, as you can see by comparison with this example (from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford), which was made in Italy around 1570, and is attributed to Girolamo Virchi. Citterns tend to have a flat back, as opposed to the rounded back of the lute, and the strings are made of metal, as opposed to the gut, which is used for lutes. As a result, they sound very different. In the interpretation of Dutch 17th century paintings this difference is important for a very specific reason: the Dutch word ‘luit’ was used as slang for the female genitalia – which can have implications for any woman holding a lute, or any man playing one anywhere near a woman… Nevertheless, the cittern is still a musical instrument, and given that we are in the 17th century, and that Shakespeare probably wrote Twelfth Night around 1601-02 at the beginning of the century, it is well worth remembering that the play opens with the lines,

If music be the food of love play on

Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken, and so die.

So, as likely as not, given that the woman is (or was) playing music, we are probably being invited to think that she is in love. The paintings in her room support this suggestion.

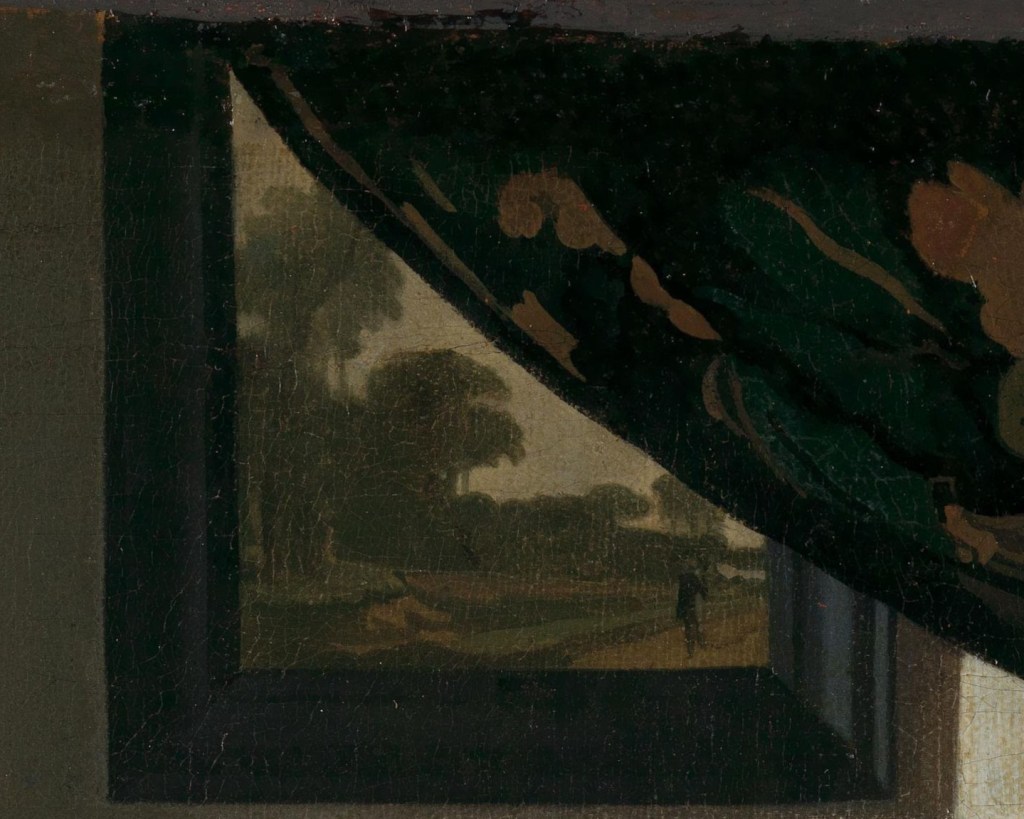

Not only has drawing back the curtain allowed us to see what is going on in the inner room, but, as this detail shows, it has also revealed most, but not all, of the upper of two paintings. I’m sure there’s not much we can’t see, as the curving line of the fabric traces the height of the distant trees: all that is hidden must be sky. This could be a version of a real painting. As we will see on Monday, it was quite common for Vermeer to use paintings he knew. Some were in his mother-in-law’s personal collection, some were by artistic associates – members of the Guild of St Luke in Delft – and some might have been passing through his hands as an art dealer. However, he would often edit them, taking just one detail, or changing their scale, according to the composition he was working on. I don’t know if anyone has ever found a source for this particular image, but I’m sure the trees have been edited to fit the curve of the curtain. It is a landscape (though in a portrait format, but this isn’t unusual), with a path or track leading towards us in the bottom right corner. There is a single figure, which I see as a man walking towards us – his two legs are distinct (a woman would be wearing a full-length skirt). I’m assuming he’s walking towards us as that was a reasonably common occurrence in Dutch landscape paintings. He is, arguably, the last thing to be revealed by drawing back the curtain, leading us to ‘dis-cover’ (quite literally) a man approaching us. This may well relate to the contents of the letter, which might inform the lady that a man is returning from the outside world.

The lower painting is another common genre in Dutch 17th century painting: a seascape. Billowing clouds are seen against a clear blue sky, and are lit at the top by bright sunlight – fair weather, if windy. There is a single sailing ship approaching us, listing to port (OK, I don’t know ships well enough to tell if it is approaching us or going away – but it makes sense to me that it would be approaching, in which case I can at least tell it is listing to port… or, leaning towards the left in the direction of travel). Notice how the maid is so overtly associated with this painting: her shoulders are painted against the lower edge of the frame, so that her head is framed by the ebony surround. Her tall, rounded, white headdress catches the sunlight coming through the window of the inner room in the same way that the clouds catch the light in the painting.

Seascapes can refer to many different journeys – our journey through life, for example, or the status of a relationship: ‘Stormy weather, since my man and I ain’t together’, to quote Ted Koehler (1933). Here the sky is blue, the clouds are fluffy, and even if the sea must be rough because of the wind (the bottom of the painting is not at all clear) it does imply that the person on the ship is making a speedy journey. The two paintings suggest – to me at least – that someone is on their way home and making good time. I’m assuming it is the lady’s lover… It is not clear whether she is married or not, though. And is she really the lady of the house, or one of the daughters? Is this an accepted relationship, or a secret between her and her maid? Again, Vermeer gives us all of the clues – but doesn’t draw any conclusions. We are left to decide, and then, if we so choose, to moralise.

There is no doubt that this woman is a member of a wealthy household, though. It’s not the art – most members of the merchant classes in the Dutch Republic (who were, after all, the ruling classes in the 17th century) had paintings, and many paintings, on their walls. But the brilliant illumination implies large windows, which implies a lot of glass, which implies a lot of money. The gilded leather panel also suggests wealth, even if it wasn’t especially expensive: this example was one of Vermeer’s studio props, and also appears in his Allegory of Faith. The mantel piece was also a way of showing off your wealth, with carved columns supporting a projecting shelf. It could be carved from wood or stone, or, for the richest, fine marble. To be honest, it’s hard to tell what this one is made of – it could be painted wood, or it could be stone, but not, I think, marble: this isn’t the richest of houses. There is also a dark green satin pelmet around it to make it look more refined. One of the things that is not as expensive as it appears is the lady’s jacket, which is the same as the one worn by The Guitar Player. The original probably belonged to Vermeer’s wife, and is mentioned in the inventory drawn up in 1676, the year after the artist’s death: a ‘yellow satin mantle with white fur trimmings’ – it was kept in the ‘groote zael’, or great hall. For those of you familiar with ermine, the fur worn by members of royalty, you will realise that this doesn’t look quite right: the black spots are too large and irregular – and don’t look like the tips of tails. This is a cheaper white fur (possibly rabbit) which has been died with black spots – to look like ermine. This is the sort of information you can find in what is my go-to source for Vermeer – Essential Vermeer. People often ask me what books I recommend, but I think this website beats everything for the amount of information it covers, the detail it includes, and the number of different approaches to Vermeer and his art that it explores. I’ll see you in 2027 when you’ve finished reading it all…

Whatever its material, the mantelpiece is profoundly rectilinear, with the vertical column supporting a horizontal mantel. The paintings, too, emphasize horizontals and verticals, and are framed by the vertical door jambs. This allows us to measure the movement of mistress and maid – the former leaning to our right, the latter tilting her head to our left. Notice how these movements echo the forms of the two highest billowing clouds in the painting behind them, and how the lean of the lady echoes that of the ship, as if she too is listing in the wind.

As I’ve already suggested, neither is doing what they probably should be doing. A laundry basket has been placed on the ground in what I presume is the groote zael of this house – which I imagine is not the right place for laundry. The maid could have plonked it there while delivering the letter. Next to it is a blue sewing cushion – and sewing, which implies occupying yourself in a focussed manner to put something right or to make something good, was commonly seen as indicating domestic virtue, something that every good woman should aspire to. And yet, the sewing cushion has been put aside, left on the floor (not even on a table), while the lady sits and strums. But then, If music be the food of love…

Despite the blue sky in the painting, maybe things are stormier than we think – it’s not plain sailing. The dark, dirty streaks on the wall beneath the map could have told us as much – and despite the brilliantly illuminated interior maybe the outlook is not as bright as it might appear: there could be clouds on teh horizon. But remember, this is just one interpretation – there are many others which could be equally (or more) valid. And, as we shall see on Monday, that is one of the things that keeps bringing us back to Vermeer.

Dear Richard,

I just finished reading Andrew Graham-Dixon’s book Vermeer: A life lost and a life found. It has mixed reviews but I couldn’t put it down. I will never see a Vermeer in the way I used to see them. He has totally changed my perspective and cleared up several mysteries. I strongly recommend it.

Thanks so much for previous info on attending the Fra Angelico exhibition. I’m going in January and look forward to it.

kind regards,

Bernie Baker

LikeLike

Thank you, Bernie – I’m glad you enjoyed AG-D – although I’m afraid I probably won’t get to read it. I manage to skim half a catalogue before each talk and then have to move on! But maybe one day, who knows?

Enjoy Fra Angelico – I’d love to go back!

LikeLike

I zoomed in on the ship in the Rijksmuseum’s Closer to Vermeer website and it looks to me as if it’s sailing away, I’m afraid! So heeling to starboard with the wind on the port beam. You can tell because the banner at the stern is blowing to the right from the staff, with the sail beyond it. You wouldn’t have such a large flag at the bow where it would obscure the forward look-out.

Maybe the lover has run away to sea and the maid is saying “Told you so… “

LikeLike

Thank you! The more I looked, the more I was beginning to suspect that the boat was moving away – as much by the shape of the main sail and the position of the mast. But, whatever it’s indicating, despite the blue sky, I don’t think it’s plain sailing!

LikeLike

Dear Richard,

I wonder if I am paying twice for tickets now. It may have happened when I was on holiday in the Wirral, so if I buy a ticket, I seem to get two replies with tickets!

Is it possible to remove one of my accounts.

Best wishes

Margaret Rice-Oxley

Sent from Outlook for iOShttps://aka.ms/o0ukef

LikeLike

Dear Margaret,

You have booked twice for Vermeer and Turner & Constable, and I have asked them to refund one of the ticket fees for each. You have only booked once for Picasso, though. I’m afraid I can only think that you booked twice by accident yourself – it is not something the system could do… it will only book you the number of tickets you ask it to book. As for having different accounts, I’m afraid I don’t know what that refers to – apologies – but anything you have on the system you should be able to access. If the problem continues, could I ask you to contact Tixoom directly? They have more access to your bookings than I do, and know how their system works – thank you,

And best wishes,

Richard

LikeLike

That was an excellent read, with so much to speculate on, and you don’t do the thing that many art historians do (or used to) where they state speculation as fact, thank you! Definitely one of my favourite artists, well he’s almost everyone’s favourite artist! The well-dressed woman looks to me a little like the sitter in Girl in a Pearl Earring, the slant of her eyes. I’m imagining her with the blue scarf around her head. She has such an amusingly guilty expression, like a little girl caught eating cakes from the cupboard, and I love the maid’s ‘I know what you’re up to’ expression. Those slippers are so gorgeous that I sought something similar for myself, and found them in a pair of Timberland black leather sandals! I adore the blue of the maid’s skirt. Prussian blue maybe? Mixed with viridian and white? With black in shadows? I don’t know what they called colours in those days, I think Prussian blue was around?

LikeLike

Thanks, Rose, I’m so glad you enjoyed it. I’m really not a fan of ‘proof by assertion’, or ‘proof by repetition’ which still do occur often enough, and I’m glad that more art historians are willing to confront the uncertainty.

The blue is probably ultramarine – Vermeer tended to use the best! Prussian blue didn’t really come in until the 18th century…

LikeLike