Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Musicians, 1597. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The two one-painting exhibitions in London at the moment have a lot in common, and so do the artists who are represented. Apart from anything else, music and love are major themes, and in my blog last week I quoted the opening of Shakespeare’s play Twelfth Night – ‘If music be the food of love…’ The same quotation is relevant today, so… play on! However, in Caravaggio’s Cupid, currently on show at the Wallace Collection (the subject of my talk this Monday 15 December at 6pm) love triumphs over music – and everything else, for that matter: omnia vincit amor. This is my last talk for 2025, but I’ll be back in the New Year to introduce Tate Britain’s superb show tracing the relationship and rivalry between Turner & Constable. That will be on Monday 5 January, and I’ll visit Tate Modern the following week (12 January) to explore Theatre Picasso. This truly lives up to its name: it is the most dramatically staged exhibition I have seen for years. I’ll be going to Hamburg shortly after to see the Kunsthalle’s exhibition dedicated to Swedish master Anders Zorn. He was one of a triumvirate of painterly, impressionist-inspired masters, perhaps not as well known as the other two, John Singer-Sargent and Joaquín Sorolla, but equally brilliant: I’m really looking forward to it, and to telling you all about it on 2 February. Before that, though, I want to look at another Scandinavian artist, Anna Ancher, to give you more of a chance to see her marvellous, calm and colourful paintings which are currently on show at the Dulwich Picture Gallery. I saw the exhibition earlier this week, and was completely won over. I will be talking about her on 26 January, and will get more information onto the diary as soon as I can!

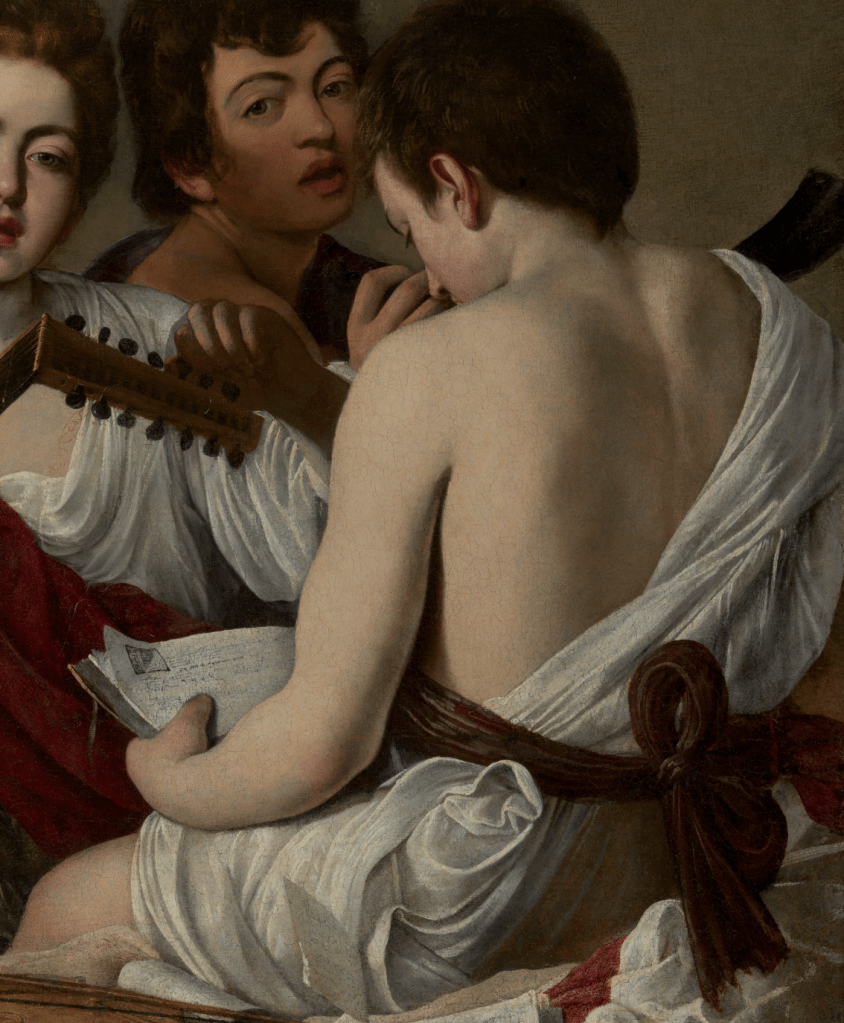

Today’s painting is typical of Caravaggio’s early work, depicting half-length, contemporary figures clearly and crisply, using rich colours, and often including beautifully detailed still life elements. His subjects were cardsharps and fraudsters, fortune tellers and gullible youths, boys offering food and wine, performing or being out-manoeuvred: the vulnerable and the manipulative inhabitants of the low-life world he had come to occupy in Rome. He settled in the Eternal City in 1595 at the age of 24, having first arrived there a few years before. In this particular work there are four youths who seem more interested in us, or in what they are doing individually, than they are in each other. They are closely, almost claustrophobically arranged, a compact composition in which the figures overlap and interlock, thus making them, of necessity, a ‘group’, even if they are not currently interacting. This is demonstrated most clearly, I think, if we try and focus on the individuals. In the details that follow, I have cropped the image to include everything that we can see of each of the four figures – and have added other details in between.

Most prominent is the lutenist. While music is clearly a major theme of the painting – these are, after all, The Musicians – no music is being played. This boy, or man – it is hard to pinpoint his age – is currently tuning his lute. His left hand turns one of the tuning pegs, while his right thumb plucks a string, the tips of his fingers resting on the teardrop-shaped soundboard. Rather than looking at his instrument, he gazes out towards the viewer – towards you – his eyes half closed and his mouth half open, a face that is totally relaxed, and either seduced or seducing. His auburn hair contrasts with dark, arching eyebrows, creating an appearance that is both unusual and arresting. We know that this is one of the first paintings – if not the first – that Caravaggio made for his patron and host the Cardinal del Monte when he became part of the prelate’s household, the Palazzo Madama, not far from the Piazza Navona. As well as being interested in the visual arts, del Monte was also an active patron of music, providing financial support for the training and performance of young castrati, the male sopranos who were an essential feature of the musical culture of the time. If this musician was one of their number, it might explain why his appearance is so arresting, and why his precise age is hard to pin down.

Technical analysis shows that his right arm was painted first, and then the full, red drapery which encompasses it was added on top. The brocade cloak, or shawl, flows over his elbow and frames his hand, its curve echoing the arch of his wrist. It fills out the figure, and broadens the form, and it is this, as much as anything else, that gives the lutenist his prominence. From his shoulder the brocade crosses his body on a diagonal, in opposition to the neck of the lute. Together they form an ‘X’ in front of his chest, the top ‘V’ of which helps to frame his sultry gaze. His left elbow is hidden behind the unclad arm of the boy on the right, while his head tilts towards that of the figure at the back.

The sculptural form of the lute is precisely defined. The soundboard catches the light entering the room from the top left, while the back, or shell of the instrument is cast into shadow, with the exception, perhaps, of the top ‘rib’. However, there is not much detail, and we can’t see all the strings. Sadly, despite its wonderful appearance, the painting is not in a very good condition. After the death of the Cardinal, the painting passed into the hands of a French collector, and was later briefly owned by another Cardinal, the famous (or infamous) Cardinal Richelieu. However, by 1675, we know it belonged to the Duchesse d’Aiguillon, as it is mentioned in an inventory of her collection. By then the canvas had been stuck to a wooden support, from which it was later removed. At either stage this may have resulted in losses to the surface, and could, consequently, explain the lack of detail in some parts of the painting (I’m indebted to Keith Christiansen’s 2017 catalogue entry for this painting on the Met’s website – you’ll have to scroll down and click on their ‘catalogue entry’ button – and, while I’m about it, I’d also recommend his Instagram feed: @keithartnature).

Despite the damage, details have survived – the subtle variation in the angles of of the fourteen pegs, and the light catching the strings passing over the end of the fingerboard, for example. There is even a beautiful and delicate arabesque formed by a long, untrimmed string, spiralling away from one of the pegs and over the lutenist’s brightly illuminated chest.

The figure at the back is also a musician: he holds a cornett, or cornetto. In case you are, like me, unfamiliar with this baroque instrument, I have included an image of a 17th century version – from the Museu de la Música in Barcelona – which I have rotated to be in a roughly equivalent position (however, they do come in many different lengths and forms). If you want to know how a cornett is played, and what it sounds like, there is a good video on YouTube made by The Academy of Ancient Music (apologies for the ad – you’ll be able to skip it after a few seconds).

The cornett player in our painting, like the lutenist, looks out towards us with his mouth slightly open, and has similar dark, arched brows – although they are a better match with his hair. Being in the background he is also more in the shade – helping to create what limited depth in the painting there is. This is enhanced by the darkness of his hair, and the black fabric which is draped over his left shoulder (at the back) but not, it seems, his right (the shoulder closer to us). We can see the curve of this shoulder outlining the hand tuning the lute, not far from his own right hand, holding what must be a fairly short, so high-pitched, cornett. We also see the hint of a white sleeve – but that could be either around the cornett player’s right wrist, or the lutenist’s left forearm. This apparent elision of forms brings the two figures together, as does the mutual lean of their heads, tilting towards each other on the picture plane, even though one figure is closer to us than the other. The implication is that these people are in harmony with one another, even when they are not playing. I was about to say ‘even when they are not performing’, but they are definitely performing – either for us, or for Caravaggio – turning to to look at us with their mouths open and those ‘come hither’ eyes. They might conceivable be singing, but I think sighing would be more likely. Having said all of that, you may recognise the cornett player, as the same model occurs in paintings throughout Caravaggio’s career.

It is universally accepted as a self portrait. These two images may not look identical, but it’s worthwhile remembering that the artist was 26 when he painted the image on the left (although I can’t help thinking that he was flattering himself somewhat – making himself look more like ‘one of the boys’), whereas Ottavio Leoni’s drawing, a detail of which is on the right, dates from 1621, eleven years after Caravaggio’s premature death at the age of 39, when he had lived through at least a decade of difficulty. Why he should choose to put himself into this composition is not clear – although it would undoubtedly have placed him at the heart of the Cardinal del Monte’s establishment, thus making him look both cultured and sophisticated: he clearly knows about music… and love. You could even argue that he was trying to show us that he had risen above the low-life… although we know that he himself hadn’t, and wouldn’t. His paintings, however, did, becoming predominantly Christian in subject matter, and he would later show himself as an onlooker at many religious events, and even, sometimes, as a participant, as we saw last April with 221 – Caravaggio: the witness witnessed.

If we move on to the third character, the way in which all four are interlocked and indivisible is especially clear. Although I have cropped the detail to include everything we can see of this boy, and nothing more, we can still see all of the self portrait – cornett included – and half of the lutenist. Caravaggio painted directly onto the canvas from the live model, rather than relying on preparatory sketches, whether drawings or painted studies (none of either survive). This was one of his most remarkable innovations. However, it would be a mistake to think that he had all four people in front of him at the same time. They appear to have sat for him individually, and the precise, controlled composition slots them close together like a well-cut jigsaw. Precisely how these four figures could have occupied the three-dimensional space is not entirely clear: if this were a real space, there might not even be enough room for all of their limbs. However, until we start to question this, it is not a problem, especially given that the patterning of the surface is so good. In some ways, the composition is not unlike another form of composition: music. Primary and secondary themes play off one another, with melodies interlocking and interweaving just like these people. The character of each is distinct, although not necessarily thoroughly developed. This boy in particular is a bit of a mystery: we don’t know what he looks like, even if we can see ‘more’ of him: he appears to be wearing the fewest clothes. If we hadn’t realised before, what becomes clear from the figure in white is that, if this is a scene from contemporary life, then these models are in costume: no one has ever dressed quite like this in everyday life. He appears to have a sheet slung over his right shoulder, which crosses his otherwise naked back (which is accurately, subtly and brilliantly modelled) on a diagonal. It is tied around his waist with a thick, dark, plum-coloured sash. The boy is sitting on the edge of a box, or table, slightly higher than the lutenist, and looks down at a musical score in what I read as calm, focussed preparation.

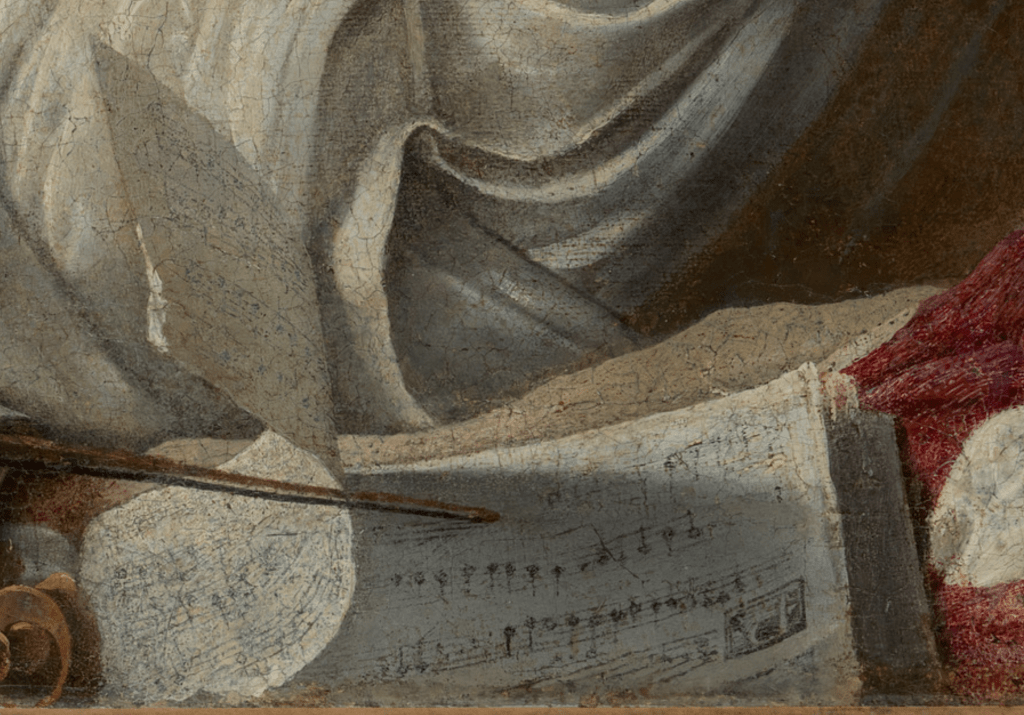

However damaged the surface of the painting, we can tell how brilliantly crafted this manuscript was. The music cannot be read, but we can tell the difference between the thick, pinkish cover of the book and the darker edges of the pages, and then see the light catching the corners, where the top page has curled up, casting its own corner, decorated with a large letter ‘B’, into shadow.

This book is just one of the still life elements in which Caravaggio both delighted and excelled in the earlier stages of his career. Another score sits on the table with a violin resting on it. They are so brilliantly conceived that I will show you more details below. The sash is tied in a bow, the ends of which appear to caress the white fabric beneath them. Bows like this occur more than once in Caravaggio’s oeuvre, and here, as in other places, it is as if we are being invited to tug on the end, and release the bow, or to toy with the loops, or the knot – but that’s probably an idea that I am transferring from another painting, Caravaggio’s voluptuous, seductive Bacchus in the Uffizi. If you don’t know it, click on that link! In our painting, the white drapery forms a turbulent swirl just beneath the belt, and wraps in numerous folds around the boy’s thigh. There is clearly enough fabric to cover his knee, but enough leg is visible to prove a point: these models are wearing less than they would normally.

This manuscript is an especially bravura piece of painting, with one page curled up, catching the light on one of the battered corners at the top, and casting shadow on the page beneath. The curl of the page mirrors the curl of the drapery next to it, and forms a counterpoint with the folds behind. Again, the music is illegible – which it may always have been – although this section was so badly damaged that a fair amount has had to be reconstructed, apparently.

The still life continues to the left with the violin – we have just seen its bow resting on the shadowed page. Caravaggio is known to have owned both a violin and a lute, and both appear in the Victorious Cupid currently on show at the Wallace Collection which we will be looking at on Monday. However, it seems too small to be a violin, certainly when compared to the lute. It could be a violino piccolo – a feature of baroque music – but it might simply be that, like the models, Caravaggio was looking at the instruments at different times, and adjusting the size according to what would work for the composition.

The still life extends to the bottom left corner of the painting, where we see vine leaves just catching the light, extending from the perfectly painted bunches of grapes above them. In between them and the end of the violin is the knee of the lutenist, who, like the boy with his back to us (is he the violinist? Or a singer?) has an uncovered knee, so close to the front of the painting that you might even think that it is in easy reach. Close to his hand resting on the soundboard – the hand that will pluck the strings – are two more hands plucking grapes.

These belong to the figure who takes up the top left corner of the painting. We see almost the full length of his right arm – a vine leaf gets in the way of his wrist – and just the ends of his left fingers. We can also see his shoulders and some of his chest, but there is no evidence that he is wearing any clothes at all. But then he does have wings: is this Cupid, or another performer dressed up as Cupid? His quiver hangs over his right shoulder on a very thin thread, with the sharp points of five or six arrows projecting from behind his right arm. Apart from this very thin strap, there is no sign of any other attachments: he is not ‘wearing’ the wings, so they must be part of him. This tells us that it is the God of Love himself, Cupid. He echoes – and transposes – the pose of the figure on the right. One of them is turned towards us, the other is turned away, but each has an unclad arm fully visible, and both look down, intent on what they are doing. Both also convey a sense of innocence, in opposition to the open-mouthed worldliness of the companions they are framing.

But why grapes? One suggestion is that, if this is Cupid, then we are clearly in the world of allegory, and while the other three are musicians, they are also a representation of the idea of ‘Music’ – which is what an allegory is. Most artists at this time, when painting an allegory, would have turned to the textbook, Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia. Published first in Rome in 1593, I would suggest that this may just be too early for it to be entirely familiar in 1597. In 1603 a second edition included illustrations, which were often more influential – and we are definitely to early for that. As a feminine noun, La Musica, like so many other personifications, was seen by Ripa as a woman – but Caravaggio was never one to follow the party line. As it happens, Ripa does mention a lute and a viol (an early form of violin, which the latter ‘eclipsed’ in the 17th century) and an open score, but he also says that music should be shown with wine, ‘perche la musica fù ritrovata per tener gli animi allegri come fà il vino…’ (‘because music was found to keep the spirits cheerful like wine does’). Maybe we’re getting in there early with the grapes, which Cupid is plucking in preparation. This was Caravaggio’s first Cupid – young, innocent, busy. A few years later, and painting for Vincenzo Giustiniani, his next major patron (who lived just round the corner from del Monte), Caravaggio would produce a very different image, brash, bold, and inherently destructive. It is that Victorious Cupid which we will be talking about on Monday.