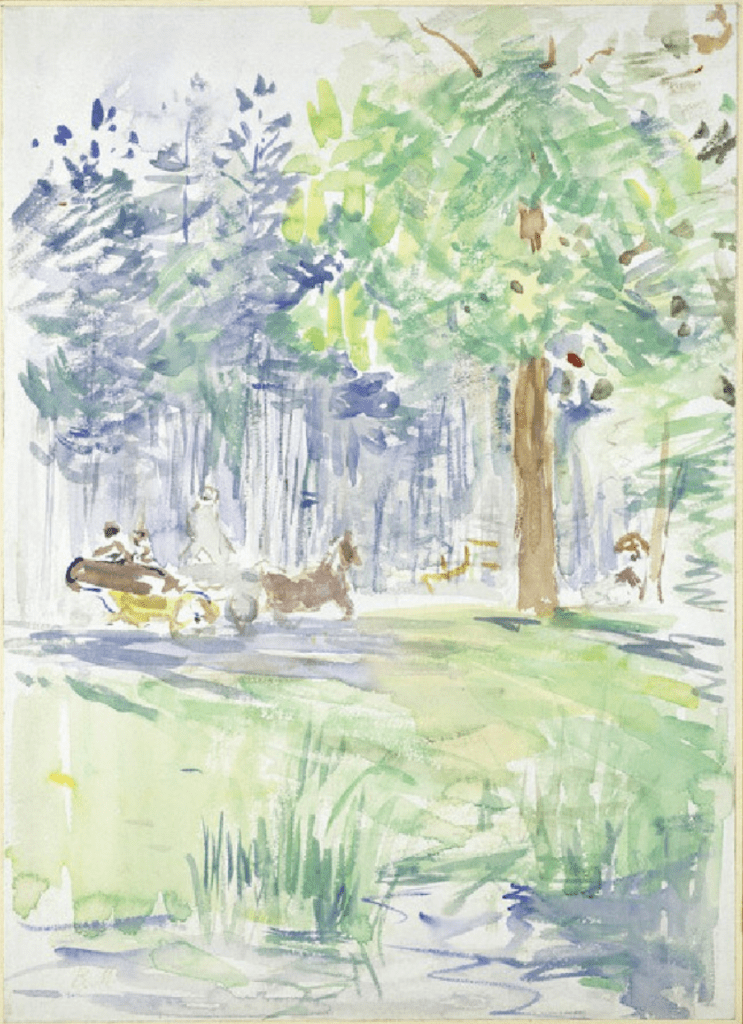

Berthe Morisot, A Horse and Carriage in the Bois de Boulogne, after 1883. The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

If you want an exhibition to help you cope with the stress of Christmas, or to get you going – gently – in the New Year, you could do worse than heading to Impressionists on Paper at the Royal Academy – the show I will be introducing this Monday, 18 December at 6pm. Each painting or drawing is a delight to the eye, and includes the most famous, such as Monet and Van Gogh (admittedly not an Impressionist…), as well as some who are less familiar: I’ve been particularly struck by the works of Zandomeneghi. There will then be a break for Christmas, and I will return in the New Year determined to increase our knowledge of the different techniques used to make prints – thanks to the National Galleries of Scotland and their exhibition The Printmaker’s Art: Rembrandt to Rego. On that link you can book both talks at a slight discount, or you can book the free-standing talks individually. On Monday, 8 January I will talk about the earlier artists (1: From Rembrandt…), and then the following week, 15 January, we will get up to the modern day (2: …to Rego). I am also offering some more in-person tours of the National Gallery in London. The morning tour of The Early Italians filled up very quickly, so I will do another at 2.30pm on Wednesday, 17 January. For those who have done this tour I am also doing ‘National Gallery 2’ – i.e. The Early Renaissance (in Florence), but you don’t have to have been on the first to do the second, and there are still just a few tickets left on Tuesday, 16 January in the morning (11.00am) and afternoon (2.30pm). All this information is also in the diary.

I’ve written about Berthe Morisot a couple of times before this year, in March, when the Dulwich Picture Gallery staged their exhibition of her work (see 192 – Role Reversal), and before that, in February, when I was delivering a series of talks on women artists (186 – Morisot and Motherhood). But I wanted to look at her again today because, in many ways, she was the archetypal Impressionist, and because her works on paper best express that idea. Indeed, as Ann Dumas says in the catalogue of the RA’s exhibition, ‘Watercolour was ideally suited to Berthe Morisot’s fluent, luminous technique as her evocation of a summer’s day in the Bois de Boulogne reveals’. Similarly, Christopher Lloyd tells us that her watercolours ‘were constantly praised at the Impressionist exhibitions for the variety in their execution and wide-ranging subject matter’. As it happens, the fluent, flickering brushstrokes were commented on by contemporary critics, some of whom noted their ‘feminine’ nature. They too pointed out the fact that this made Morisot one of the best exponents of the style – but this was not necessarily a compliment. It fed into the idea that the artists were imprecise, and created works of art which were not ‘finished’. The ‘femininity’ was, if anything, a criticism, the sign of a lack of focus. If I’m honest, I’m not convinced that we have entirely escaped this condescension, as the context of the quotation from Christopher Lloyd’s essay reveals. While talking of Édouard Manet, he says,

‘Watercolours by his sister-in-law, Berthe Morisot, were constantly praised at the Impressionist exhibitions for the variety in their execution and wide-ranging subject matter. Indeed, the brushwork of Morisot’s stronger watercolours is comparable with Manet’s in its energy and confidence.’

First, I would suggest that defining Morisot primarily as Manet’s sister-in-law, rather than putting that fact into a bracket or subordinate clause, could be seen as belittling her status as an artist in her own right. Second, we could also argue about the use of the terms ‘energy’ and ‘confidence’, which, like the comparative ‘stronger’, could be seen as masculine qualities, particularly when compared to Manet. This might imply that the more ‘male’ Morisot’s work was, the better… You might disagree with me, and fair enough if you do, I’m probably being over-picky, but the fact remains that Morisot exhibited in seven of the eight Impressionist exhibitions – three more than either Monet or Renoir – and was a prime mover in the organization of the group. In the exhibitions she was given a status equivalent to that of her male contemporaries, as the following extract from the catalogue of the ‘first’ exhibition shows.

At the time the group called themselves ‘The Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc.’ (…it was never going to catch on!), and they were listed alphabetically in the catalogue. As a result, ‘Mlle MORISOT (Berthe)’ comes after ‘MONET (Claude)’. Both exhibited nine works, and each included four oils, and five works on paper. This in itself is part of the rationale of the Royal Academy’s exhibition: works on paper were exhibited alongside oil paintings, and given an equal status, arguably the first time that this had happened. Enough talking, let’s look.

The first thing to notice is that trees are not necessarily green. Sometimes they are blue – but they are only blue when they are in the shade. Following the general theory that shadow is the absence of light, together with the idea that sunlight is predominantly yellow or orange (depending upon the time of day – and, of course, artistically rather than scientifically speaking), then the absence of that light would be represented by its opposite. If you set out a simplified colour wheel, then yellow is opposite purple, and orange, blue. Hence the deep blue (or maybe indigo?) shadows that we can see here. We are in the Bois de Boulogne, the much-frequented pleasure park on the edge of 19th Century Paris, which by now is well within the suburbs. The horse and carriage can be seen on the left of the painting, standing out as a result of the brown and ochre hues with which they are painted, different from the otherwise pervasive blues and greens.

However sunny the bright green and greeny-yellow leaves of the tree on the right might appear, the sky is not blue. Morisot leaves the paper blank, a use of the non finito – to use an Italian term for ‘unfinished’ – for which the Impressionists became famed. You don’t have to say everything, after all, as long as you say enough, and the presence of this ‘space’ at the top of the painting is enough for us to know that we are looking at the sky. Actually, there is a very pale wash which takes up some of this space, but elsewhere the white of the paper constitutes one of the luminous, unifying features of the work. The regular, short, dabbed brushstrokes are another. From this detail alone we can’t see the trunks of all of the trees, nor can we see where the trees are growing. Nevertheless, the blue of the leaves on the left and the light greens on the right help to bring the latter forward, and make the former recede. If we check with the full image (above and below), this is confirmed: the ‘blue’ trees are beyond the track along which the horse and carriage are driving, while the ‘green’ tree is on our side.

The white of the sky is reflected in the pond at the bottom right of the painting, with the blues here being the reflections of the shadows in the trees, together with the shadows of the reeds growing in the water. Notice how deftly Morisot paints each individual leaf, a flick of the paintbrush which I imagine as going upwards, lifting the brush off so that the tops of the strokes are pointed like the leaves themselves. There is also a curved, zig-zag stroke of blue running through the water, an indicative feature of Morisot’s style, her ‘handwriting’ if you like, which she used when painting in oils as well as in watercolour – a daring gesture which speaks to her talent. You can also find it in the National Gallery’s Summer’s Day.

Two people sit at the back of the open carriage, painted in the same brown as the horse, which nevertheless seems lighter as it is not framed by the same strokes of a deep indigo. The driver is barely sketched in, and far paler. The blue of the shaded trees, and the blue shadows cast on the grass by the trees, frames the browns of the horse and carriage, thus making them stand out clearly, as well as embedding them firmly ‘in the Bois de Boulogne’, as the title of the painting suggests. Travelling from left to right, and slightly into the depth of the painting, the carriage will soon pass behind the brown vertical of the trunk of the brightly-lit tree. The horizontal axis of the vehicle and its movement, and the vertical axis of the trunk, help to stabilise the image. Before long the riders will pass a woman who is walking away from us, wearing a brown shawl and carrying a red-brown umbrella, or parasol – I don’t know for sure that’s what it is, but I can’t imagine what else it would be. There is something of the same red-brown hue in the tree above. I have no idea what that is, but its presence helps us to pick out the parasol, and reminds us that everything belongs here.

The blues and whites of the pond, and the greens of the grass and reeds, tie the bottom of the painting to the top, thus unifying the image as a whole. The brushstrokes themselves are very different, though. At the bottom the grass is a wash of colour, and there are also long, flowing lines. At the top, as a complete contrast, there are short, broken, scattered dashes, giving the sensation, perhaps, of the leaves blowing in the wind. As well as unifying the image from top to bottom, and making sense of the painting as a two-dimensional image, the colours also help to hold it together in depth. The greens of the brightly lit tree are roughly at the same depth as those of the grass, but these are framed – in front and behind – by the shadows in the pond and the shaded, further trees. Uniting the foreground and background in this way is a technique often associated with Cezanne, and I wonder to what extent these two artists were looking at each other’s work.

At first glance this may appear to be a simple, inconsequential sketch, but I think this apparent ‘simplicity’ reveals Morisot’s innate talent. I’m not sure that everything I have mentioned was a deliberate choice, but I am sure that it came to her naturally. You’ll have to go to the exhibition to see if the same spontaneous brilliance was shared by the other artists who are included – although I suppose you could also join me online on Monday.

…thank you for another really interesting blog-post and your ongoing lecture series which, without fail, i enjoy – i’ve just booked-up the two on The Printmaker’s Art… …i was pleased to see you adding more dates for your ‘in person’ sessions in the Nat. Gallery as i’m very keen to join one, or more, of these… but frustratingly i’m unable to attend either of the additional dates as i’ll be in Paris for the Rothko exhibition and sundry other art museum visits… hopefully there’ll be subsequent opportunities…

>

LikeLike

Thank you, Nigel – I’m glad you’re enjoying them. And sorry you can’t make it to the tours… there will be more, at the end of January, and then probably every two weeks or so.

Enjoy the Rothko – I think I’ll be there at the end of that week!

All best,

Richard

LikeLike