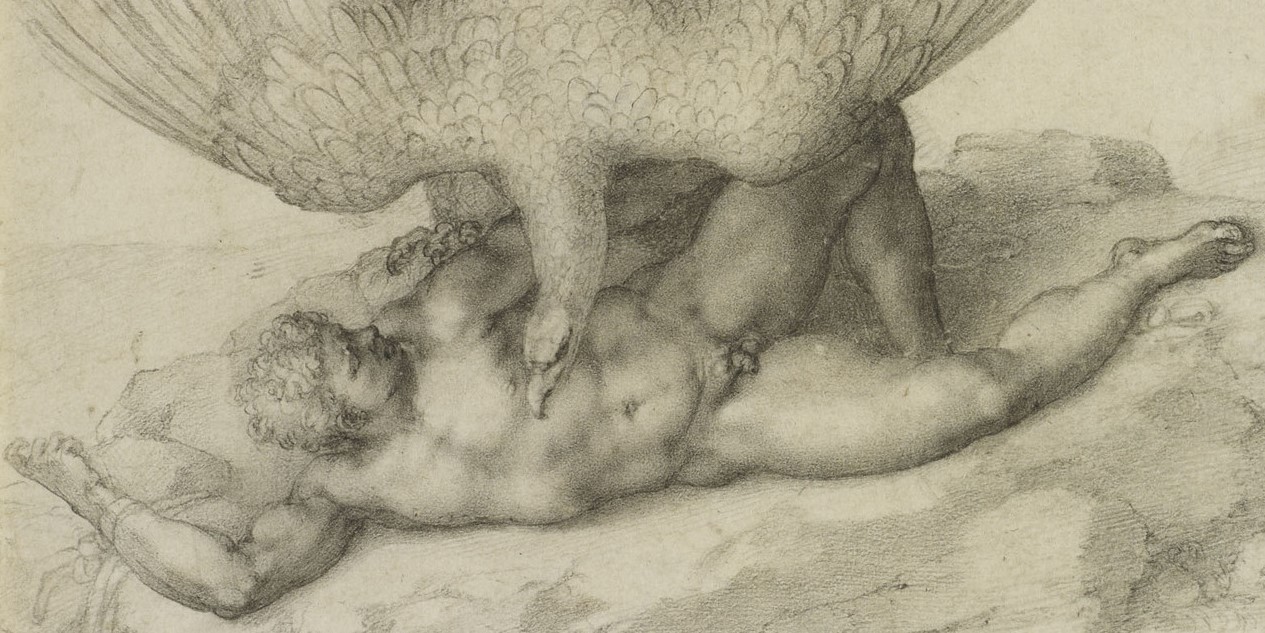

Michelangelo, Tityus, 1532. Royal Collection Trust/HM King Charles III. RCIN 912771 r. & v.

The phrase is, of course, ‘two sides of the same coin’, but today I’m looking at a piece of paper. However, ‘two sides of the same piece of paper’ isn’t a figure of speech… The sheet in question is included in the British Museum’s current exhibition, Michelangelo: the last decades, which will be the subject of my talk this Monday, 3 June at 6pm, and I wanted to take the opportunity to tell you how brilliantly I think the exhibition has been curated and designed. This particular sheet of paper, and the way in which it has been displayed, will, I hope, demonstrate the fact. The following day I will be heading off to Venice, In search of Giulia Lama – a forgotten late-baroque master. As well as being the title of my next talk, on Monday 10 June, it is also what I am planning to do: I am physically going in search of her work. A number of her paintings have recently been conserved, with funding from the charity Save Venice, and they are currently on view in an exhibition called Eye to Eye with Giulia Lama – which sadly comes to an end the day before my talk (I couldn’t get there any earlier). As the paintings are usually metres above eye level, and not in the most accessible churches, I can’t wait to see them up close. While I’m in Venice I will also be on the look out for anything else she painted. I already know where to look, to be honest, having encountered a number of her works scattered across La Serenissima during previous visits, and will let you know what I find – and what I think – on 10 June. I will then continue into the summer looking at Lama’s British equivalents – women working from the 16th to the early 20th Centuries as seen (now) in Tate Britain’s Now You See Us. I think it is such an important survey that I want to break it down into three talks, thus doing at least some justice to the artists who are represented. However, I will introduce that series with a talk which might initially seem to go against the grain, Velázquez in Liverpool. You’ll have to check out the description on Tixoom (via that link) to work out why it is completely in line with the rest of the season. The Now You See Us talks will go online soon: keep an eye on the diary. But for now – let’s look at that paper.

It is, of course, one of Michelangelo’s most exquisite drawings, and one of several made for the young nobleman Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. I will talk about these drawings in depth, while also thinking about the relationship between the two men, at the Wallace Collection on 19 June (follow that link for more information). As it happens, I have already written about one of the other drawings (see 170 – Drawing to an end), but wanted to post something new today precisely because there is something on the other side.

The story of Tityus is included in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The giant had attempted to rape Latona, the mother of twin gods Apollo and Diana. As punishment he was chained to a rock, and his liver was gnawed out by a vulture. The organ – seen as the seat of lust – grew back every night, and the punishment was repeated every day… for all of eternity. While we cannot be entirely clear why Michelangelo’s chose this subject, it seems likely that he wanted to warn the young Tommaso about the dangers of lust.

Any of you who have an eye for the birds might have noticed that the vulture looks more like an eagle – but this was a deliberate choice rather than ornithological incompetence. Another drawing for the young nobleman shows the Abduction of Ganymede, the most beautiful of boys, who was carried away by Jupiter in the guise of an eagle. By making Tityus’ vulture look more aquiline Michelangelo must have intended to link the two stories – the drawings were clearly intended as a pair. However, the meaning of the Ganymede is by no means so clear (as I will explain on 19 June).

Lying on his right side, with his left leg bent and the other extended, Tityus appears like an impotent version of Michelangelo’s Adam. His right arm is extended and tied to the rock, which means that he cannot support his own weight to raise his body from the ground, as Adam does – but then, the vulture looming over him would prevent this anyway, trapping the right hand which Adam raises towards God. This comparison might not be coincidental: as well as giving Tommaso avuncular guidance in moral concerns, Michelangelo might also have wanted to encourage artistic debate, both in terms of formal elements – the similarities and differences in the composition – and also of meaning. As a result of the Fall, Adam introduced sin into the world, and so the possibility of transgression and the need for punishment, as illustrated in the image of Tityus. Both were malefactors, even if their stories were derived from different traditions. By drawing on one of his most famous images, Michelangelo was perhaps putting himself forward not only as a moral advisor, but also as an artistic role model, while also provoking the comparison of different works of art, one of the accomplishments any cultured young person should develop.

Vasari tells us something different: that Michelangelo had produced the drawings to teach Tommaso how to draw. The technique is indeed exquisite, some of the master’s most refined work. While hair and feathers are sketched in with short, curling, expressive lines, the modelling of the flesh is handled with great softness and delicacy, defining tonal variations with small touches of the chalk which look almost like stippling. The outlines of the forms are secured with longer, bolder, taut strokes, which occasionally show signs of repetition, honing the precise form, as they do on the right bicep. The rock and the background are picked out faintly with long, parallel strokes, as is the curious, anthropomorphic tree to the right. The high quality of the work tells us that it was a presentation drawing, made as a work of art in its own right, rather than preparatory for something else – but that didn’t stop Michelangelo’s ever inventive and restless mind from sketching another idea on the back.

There are two figures on the other side of the paper. The one further up is traced from the recumbent body of Tityus, one leg bent, the other stretched, the torso sloping down toward the short edge of the paper, with the lower arm extended. Coming through the paper at the top you should just about be able to make out the dark, ominous form of the vulture’s wings – but no trace of them has been repeated here. The upper arm of the figure, hidden behind the vulture’s neck on the other side, is here more active, and some apparently abstract, geometric lines have been sketched in around the figure’s feet. All of this makes more sense if we rotate the paper by 90° and compare it to another drawing which was also executed around 1532, this one in the collection of the British Museum.

Apart from the fact that the figure has been reversed – possibly the result of another tracing – the compositions are remarkably similar, and clearly represent the Resurrection. The lines drawn around the feet in the sketchier version (on the back of the Tityus) can be seen as representing the sarcophagus from which Christ triumphantly rises, with the higher foot resting on the edge of the lid, which has been pushed back away from it. The other figure on the initial sheet is also identified as a sketch of the Risen Christ, although the way the hands are raised above the head and brought together on either side of the head, which turns to our left, makes it reminiscent of the fresco of God separating Light from Darkness, which, like the Creation of Adam, was also frescoed on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

The dramatic, active pose of Christ in the second drawing – surely a development of the first – might remind you of another image from the Sistine Chapel – but not one from the ceiling. With the right hand raised, the left crossing the body, and the beardless face looking down to our right, this particular drawing would appear to be one of the stages in the development of the central figure of Jesus in the Last Judgement on the altar wall. The commission for this fresco was precisely the reason why Michelangelo returned to Rome, where he would live for the last three decades of his life. Now, it would clearly not be possible to fit the whole of the Sistine Chapel into the British Museum, but the curators – together with the designers and what must be a brilliant team of digital editors – do have a projection of the Last Judgement which pans across the painted surface and zooms in on details which are relevant to the various drawings which are exhibited nearby – making the connection between the preparatory drawings and the completed fresco clear and easy to understand. Here is a photograph I took of the two drawings I have shown you – the ‘back’ of the first and the ‘front’ of the second (verso and recto if you want the technical terms) – and just look what you can see in between.

The curation and design of this exhibition helps you to see the development of Michelangelo’s ideas with such ease and clarity. You don’t have to flick from one page to another, or turn around to see objects on different walls while holding images in you head, or for that matter, head to Rome and back (not that that’s a bad idea…) in order to understand what’s going on. And it was this that made me realise – in the first room of the exhibition – that it would be one of the really good ones: brilliantly conceived, beautifully presented and showing works of the highest order. I do hope you can get to see it, and whether you can or not, I do hope you can join me on Monday. I can also recommend the catalogue by Sarah Vowles and Grant Lewis – highly readable and with a similar clarity of thought and design. They also point out – which I haven’t so far – that with a sketch for the Risen Christ on the back of the Tityus, not only did Tommaso de’ Cavalieri get a warning against sin, but also the possibility of redemption. Two sides of the same coin.