David Hockney, My Parents and Myself, 1976. The David Hockney Foundation.

David Hockney must surely be Britain’s most famous, and successful, living artist. He also happens to be one of those who is most interested in the art of the past, which is the point made by the National Gallery’s capsule exhibition, Hockney and Piero: A Longer Look which I will be talking about this Monday, 26 August at 6pm. In just three paintings, and some relevant documentation, it becomes clear that he has spent years enjoying the paintings in the National Gallery, and is intrigued by the many different ways we can interact with the art of the past. Today I would like to look at some paintings and drawings which don’t make it to this exhibition, nor for that matter the catalogue, but which are, nevertheless, entirely relevant. The following week (2 September) I will consider the question Who’s Who in Heaven? This is one of two talks, with the second following on 16 September. The first will look at the figures Around the Queen – focussing on Jacopo di Cione’s Coronation of the Virgin in the National Gallery, which includes as many as 48 different saints. In the second we will see who is Behind the King in the glorious Wilton Diptych. Two weeks later (30 September) I intend to take a quick tour around The Piero Trail – thus returning to Piero della Francesca, one of Hockney’s major sources of inspiration. But I’ll post that on the diary nearer the time.

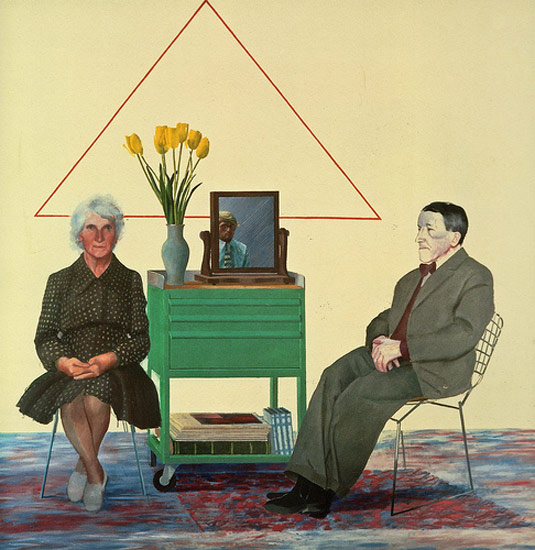

There are only three paintings in the small exhibition, but they form a perfect triptych. Nevertheless, I won’t have time to cover all of the material related to them on Monday, so this is a somewhat convoluted exploration of the origins, and implications of just one of the three paintings, David Hockney’s My Parents (1977). Above is an earlier version, My Parents and Myself, which was started in 1975 while Hockney was living in Paris, but then abandoned – much to his parents’ distress. Unfinished, it languished for decades in his Los Angeles home until seen in public for the first time in 2020. Hockney’s mother and father are seated to our left and right respectively on what looks like a square platform, with curtains slung on a rail above as if they are on stage. In between them is a bright green cabinet with a vase of yellow tulips on one side, and a mirror, reflecting the face of the artist, on the other: this is a triple portrait.

The light brown lines you can see rising above Mrs Hockney’s head, above the tulips, and to the right of the mirror are remains of masking tape which was left in place when the painting was abandoned. I can’t for the life of me think what he would have been masking here, but he might have been planning to overpaint the background and leave a geometrical framework of the underlying layer: there is a similar geometric structure in another version of the painting there were three) which we will see later. I am especially interested in curtains at the top. They are not especially detailed, but then, this is an unfinished painting. As a result it is not at all clear how they are attached to the pole, which stretches from one side of the painting to the other with no visible means of support. The light brown colour suggests that it is made of wood, but given the weight of the curtains, and the slim profile of the pole, it is surprising that it does not bow in the middle. The curtains are a jade green, or very light turquoise, and serve to frame the images of mother and father below. The curtain on the right is slightly more open, with the lower end brought forward and slung over the back of the pole further to the right. The bottom edge and corner of the curtain are visible to the right of the other folds. It spreads further than its equivalent on the left, which is slung over the pole in a more compact way: it isn’t stretched out as much, and the lower end is hidden between the folds of the front and back sections. The curtains echo the placement of the figures.

Mrs Hockney faces directly towards us, her shoulders parallel to the picture plane, while her husband is at an angle, in three-quarter profile, with his body aligned on a diagonal from back right to front left. As a result, like the curtain above, he is more ‘spread out’, while Hockney’s mother is more contained. In a similar way, there seems to be an equivalence between the objects on the cabinet and the human figures. The vase has the same light colouration as Mrs Hockney’s hair, and both have swelling forms which narrow towards the bottom, with a neck and shoulders (or equivalent) at the top. The mirror is framed with wood, and could be swivelled, not entirely unlike the diagonals and verticals of Mr Hockney’s wooden chair (Mrs Hockney’s chair is only just sketched in, but looks as if it would have had a slim metal frame).

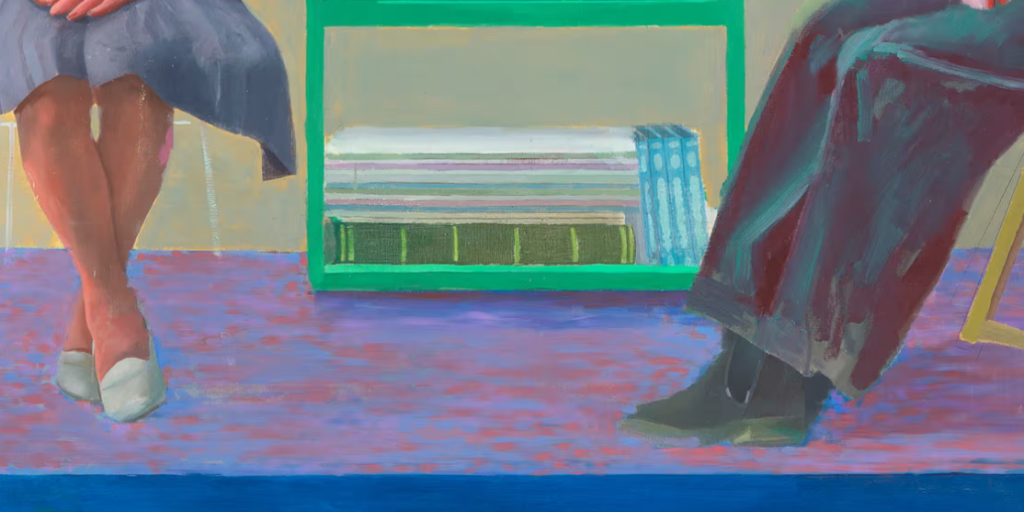

Mum’s feet are crossed over, while dad’s rest flat on the ground (I mention this as the finished painting of 1977 is different). They are on a mottled blue and red carpet, with a dark blue band at the front, one of the things which creates the sensation of them being on a platform or stage. In between them, the lower shelf of the bright green cabinet is stacked with books. A large, thick tome and several slimmer volumes of the same height lie horizontally on the left, while four smaller, light blue books stand upright, if slightly leaning, on the right.

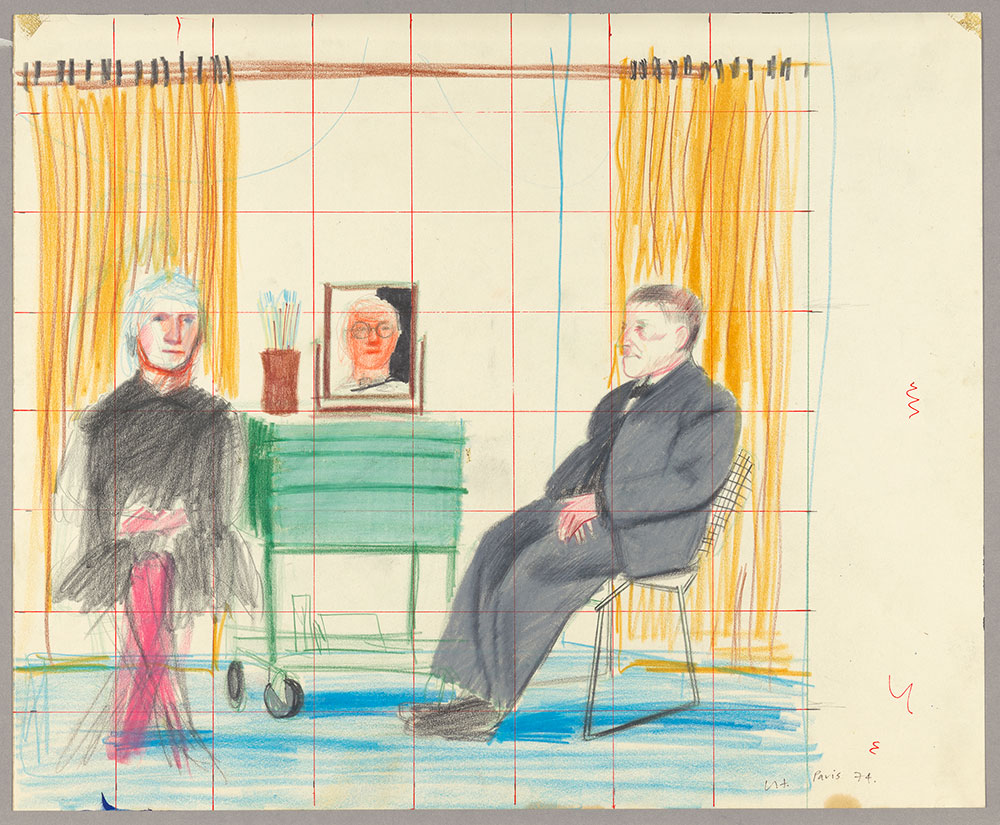

The David Hockney Foundation has a study for My Parents and Myself which was drawn in coloured pencils in 1974. It shows that the original idea for the composition was fundamentally the same, with his mother on the left facing front with feet crossed, and his father on the right, at an angle. The green cabinet is there – though on wheels, and slightly angled – with the vase (which is darker) and mirror standing on it. Hockney’s reflection is there, although his face takes up more of the surface: the intention was definitely to have all three members of the family given an equivalent presence. The curtains are very different, though. They still hang from an apparently wooden pole, but have black curtain rings clearly visible. They are a yellowy-orange, and hang the full height of the back wall of the room. Why did he change the colour, and the way they hang?

A photograph of the sitting (also in the David Hockney Foundation) suggests that there weren’t any curtains there at all – although they are present in the painting which has been placed behind Mrs Hockney (this is clearly a highly staged photograph). The light vase contains the yellow tulips, and the mirror reflects the artist – though at a far smaller scale than in the Study, given his distance. The reference to Old Master Painting should be clear. With a mirror, reflecting an otherwise unseen presence, seen between a married couple, one looking towards us, one at an angle, he can only have been thinking of the Arnolfini Portrait. In addition to Jan van Eyck, at least two other artists have influenced this painting. The books on the cabinet (which is nowhere near as brightly coloured as in the painting) are in a different arrangement. There are now five vertical blue books on the left, and fewer large, horizontal volumes to the right. The one at the top is clearly titled ‘Chardin’, and is a monographic study of the 18th Century French artist famed for his timeless still life and genre paintings. Both parents sit on the same type of chair – the wooden, angled form that the father uses in the unfinished painting – and they are both half on and half off a very specific rug.

It is a woven version of Piet Mondrian’s unfinished Victory Boogie Woogie (1942-44, Kunstmuseum, The Hague). Not an ‘old master’ perhaps, but another artistic reference, and also one which speaks of timelessness and balanced, careful composition.

I mentioned that there were three versions of the painting. Unlike the one we are looking at today (on the right) the version to the left was completed, and exhibited, but no longer exists: Hockney later destroyed it as being ‘too contrived’. This is the version I referred to which has a geometric structure, a triangle rather than the implied rectangle formed by the masking tape. The base cuts behind the heads of Mrs Hockney and her son (in the reflection), with the bottom right corner pointing toward Mr Hockney. It binds the family together. However, given my interests in religious art, and Mrs Hockney’s profound Christian faith, I wonder if there was something else? The relationship between Mother, Father and Son is clearly important, but is there also a nod towards the Holy Trinity? There is an implied reference in a painting seen in the third iteration of the composition – even if I’m not sure that Hockney would have been interested in that aspect of the work in question. Mrs Hockney seems to be sitting in a metal-framed chair – the one planned for the unfinished painting, perhaps – while Mr Hockney sits in the one seen in the pencil Study, rather than that in the photograph. The carpet stretches the full width of the painting, and the green cabinet, on wheels, is at a slight angle, as in the Study. There are no curtains.

The completed version was finished in 1977 after Hockney had returned to England. By now you can pick out the themes and variations for yourselves, but I will point out that the arrange of books is the same as in the photograph (although the Chardin monograph is now at the bottom of the pile, and there are six vertical books), and that the rug, scrubbed clean of the Mondrian, is neatly placed within the frame and on a wooden floor. As a result there is no sense that they are on a platform. The chairs, as in the photograph again, are half on and half off the rug, and it’s curtains for the curtains. Or is it? They are there, but hidden in plain sight. As you will have realised, there are a number of other differences. Mrs Hockney’s feet are not crossed, her husband’s are raised at the heels, and he bends over to look at a book lying on his lap. I’ll talk more about the relevance of these details on Monday. But something else is missing, which is reflected in this version’s title: My Parents, rather than My Parents and Myself. We do not see Hockney’s face in the mirror. However, he is reflected there, albeit symbolically.

Two images can be seen in the reflection. One is a print of Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ – the painting exhibited alongside My Parents in the National Gallery’s Hockney and Piero. The other shows a green curtain. The catalogue entry on Tate’s website suggests that this is a reflection of Hockney’s Invented Man Revealing Still Life (1975, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City) which I’ve illustrated on the right. However, the National Gallery’s catalogue for the current exhibition implies (but doesn’t state explicitly) that the curtains are those from the unfinished version of My Parents and Myself. What do you think? My personal feeling is that we are seeing a reflection of the unfinished painting. In any image of Invented Man… that I have come across, the curtain at the right (seen at the left of the reflection) is at the very edge of the painting, to the extent that it is slightly cropped in the image from the Hockney Foundation website I’ve used above. However, in My Parents and Myself there is a gap between the curtain and the side of the painting – as there is in the reflection. Not only that, but in Invented Man… we can see the black curtain hooks which Hockney had shown in the Study for My Parents which are not in the unfinished painting. They are not visible in the reflection – suggesting that it is My Parents and Myself, which must be propped against the back wall of Hockney’s studio in London. The National Gallery catalogue suggests that the reflection of the unfinished My Parents and Myself seen in the finished My Parents suggests an idea of spiritual renewal which is not entirely unlike the act of baptism. I would further suggest that the ‘missing’ figure in Piero’s Baptism – God the Father – would complete the Holy Trinity implicit in the figures of Jesus and the dove (the Holy Spirit). This would be the connection with the red triangle in the destroyed version of the painting. There is a profound sense, therefore, that Hockney is associating himself with Piero and his work. He is subtly making us aware of his heritage, as the product both of his parents, and of his artistic forefathers, his physical and artistic ‘families’.

However, none of this explains my interest in the curtains. Where do they come from? Somehow I know, but I don’t know how I know. I suspect that I’d have to read everything I’ve ever read about Hockney to find out, but I really can’t remember what that was. Nevertheless, have a look at the next two images.

The first is a detail from My Parents and Myself. The second has all the black curtain hooks in Invented Man… – and sketched in, even with different curtains, in the Study for My Parents and Myself. It also has the vertical support from which the un-bowed pole hangs in Invented Man… It is a detail from the predella panel of Fra Angelico’s San Marco Altarpiece, painted for the eponymous church in Florence and now in the eponymous museum. David Hockney discusses his love of Fra Angelico in an interview in the current National Gallery catalogue, and picks out the Annunciation frescoed at the top of the stairs in the former Dominican friary which now houses the Museo di San Marco. However, the borrowed curtains are not mentioned, so I’m very glad I remembered them [since writing this post I have found a reference to the Fra Angelico painting on the David Hockney Foundation website, on a page about the year 1975, when Invented Man Revealing Still Life was painted – but that’s not where I know it from…]. There are others references, too, adding up to an entire ethos. But that’s what I’ll be talking about on Monday.

Wonderful insight and memory! I hope Mr Hockney reads this and comments on those curtains.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I said on Monday (if you were there) I have since found a reference to the Fra Angelico – and have amended the text above accordingly. It on a page about the year 1975:

https://www.thedavidhockneyfoundation.org/chronology/1975

That’s not where I would have seen it… but the knowledge is out there!

LikeLike

Thank you! I’m sure it’s common knowledge (for the cognoscenti at least) – and if I ever went to a library to check what’s in the literature I would know, but my mind is too scattershot to focus like that…

LikeLike