Michael Craig-Martin, (title in waiting, read below), 2001. Gagosian.

I’m just back from a fantastic week in Italy following The Piero della Francesca Trail – and looking forward to doing it all again next March (go right to the bottom of the page). I’m also looking forward to picking up on Van Gogh’s idea of ‘a colourist such as there hasn’t been before’, a phrase I quoted in Monday’s talk, by jumping into the deep end, colouristically, with Michael Craig-Martin this Monday, 21 October at 6pm – the exhibition at the Royal Academy is superb. And talking of the Royal Academy, tomorrow I’m off to Manchester to see the Whitworth’s introduction to one of the most recently elected Royal Academicians, Barbara Walker – an artist who, as I keep saying, I think you should know, and whose work I think you will like. This exhibition will be the subject of my talk the following week, on 28 October.

In less than a month’s time, the Royal Academy will open this Autumn’s highlight, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c. 1504, which will form the subject of my following four talks, from Monday 11 November to Monday 2 December. Not only will this tie into my Mono/Chrome season, but it will also form the start of a longer series of talks about the Italian Renaissance, about drawing, and about different ways of thinking about the Renaissance itself. The first two talks will focus on Michelangelo and Leonardo respectively, and are already on sale. The other two will come online on 11 November after the first talk, with a reduced price for those who have booked for Michelangelo. There is more information on the diary, and via the appropriate blue links. But now, as I mentioned different ways of thinking – which can imply different ways of looking – let’s look at one of the paintings by Michael Craig-Martin which I have most enjoyed discovering, and which has most intrigued me.

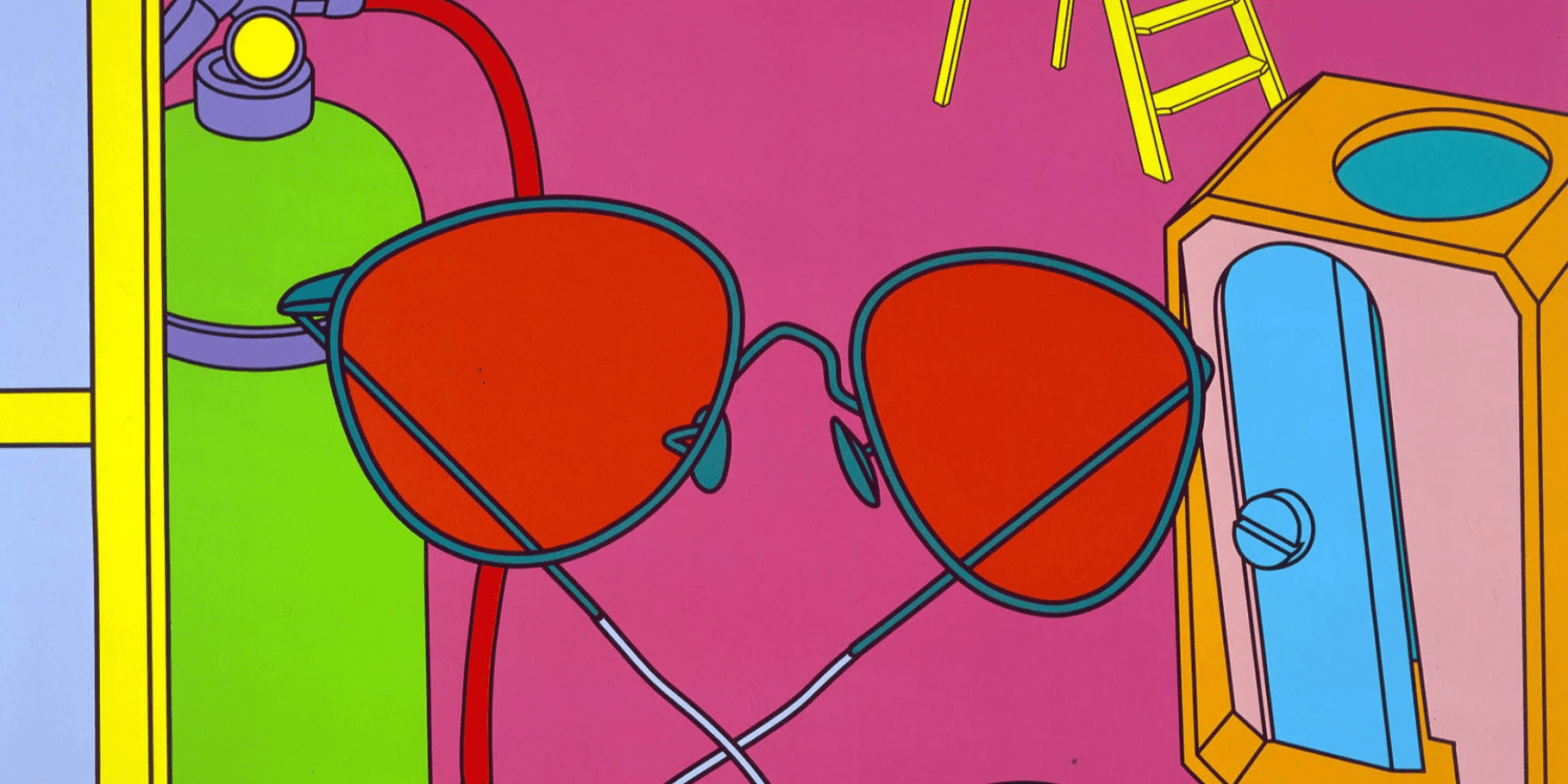

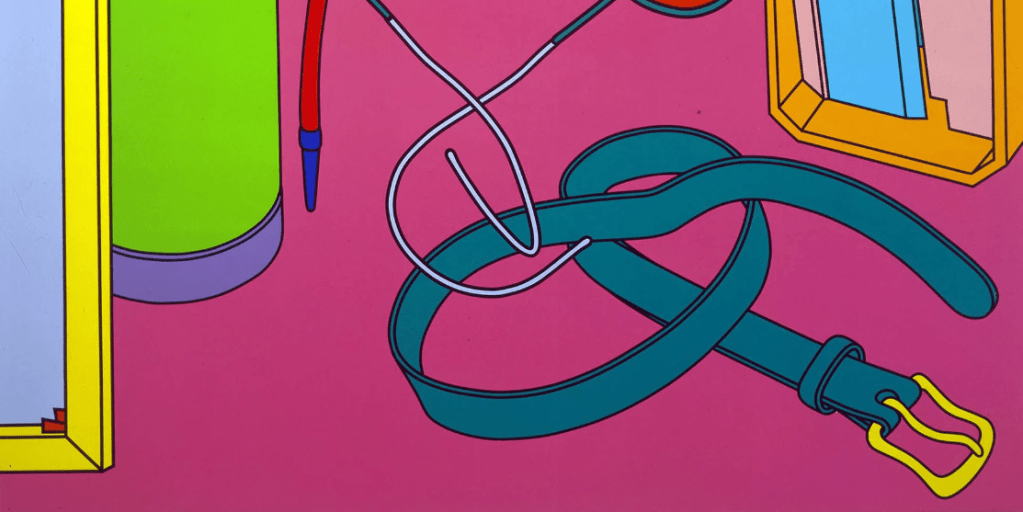

It would be easy to make the mistake that Michael Craig-Martin’s early work was highly cerebral – but that would be to deny its essential materiality, its solidity, and the implied drama inherent in its construction: so many things are only precariously secure. And in the same way, you could – and several critics do – deny that the later, highly coloured works are anything more than superficially decorative, given their saturated, attention-grabbing colour and commanding scale. But of course there is, as there always is, more to them than meets the eye. What we see in this painting is a collection of objects which may or may not be connected. Or rather, they are connected, if only because they all appear in the same painting – but is there anything else that unites them? Reading from left to right and top to bottom, we can see the back of a canvas, a mirror, a ladder, a fire extinguisher, a pair of sunglasses, a pencil sharpener and a belt. I have no doubt that these are the objects depicted in this painting, although art is subjective, and you might be seeing something else.

One of the ideas that fascinates Craig-Martin is the unavoidable fact that we do see these objects, and yet none of them are there. There is only a canvas covered with acrylic paint. Not only that, but we see solid objects, even if we know that this is a two-dimensional surface. We can identify the objects, if we are familiar with them, even though we know that they are not these colours, nor are they this size. The problem with size is a complex one, of course: everything is relative. In the painting the glasses appear far larger than the step ladder, which we know is not the case ‘in real life’. A fully grown adult could climb up that ladder wearing glasses, so they would have to be far smaller than we see them, surely? The canvas measures 274.3 x 223.5 cm, as if happens, which would make the pair of glasses more than a metre wide. However, being a sophisticated bunch of people, we read into the image the conventions of post-Renaissance painting. We know about perspective. We know that nearer things look larger, and further things smaller – so the glasses must be far closer than the ladder. They fill up about half the width of the painting, and must be hovering in front of our eyes.

Inevitably we try to make sense of what we are seeing. Indeed, we already have. I have suggested that the ladder is further away than the glasses, and that the latter are hovering. But that doesn’t make sense. Glasses don’t hover. We know, however, that artist’s make choices, and before long we ask ourselves ‘what does it mean?’. Now, Michael Craig-Martin has said, more than once and in different ways, that art should be experienced rather than interpreted, and I do hope that you can go and experience this superb exhibition in person. I say ‘superb exhibition’: it is, undoubtedly. It is a thorough display of Craig-Martin’s work, with good examples of his output representing all stages of his career from its beginning to the present day. It is well-presented, beautifully designed, and superbly interpreted. Most critics can’t get past the stage of wondering whether they like the art or not, nor are they sufficiently engaged to question whether or not it is a good exhibition of art that they do not actually like. Trust me, it is a good exhibition of Craig-Martin’s work, the best that you are ever likely to see. However, I can’t guarantee that you will like the art. I’m not even saying that it is good art (although I really do think that it is), but it is definitely a good exhibition of that art.

What Michael Craig-Martin has done is to depict a collection of objects which wouldn’t normally go together, in colours that they wouldn’t normally have, in an arrangement which might not initially appear to make any sense. And one of the results of this is that we start to ask ourselves why all of these unrelated objects are all depicted on the same canvas. He wants his art to be experienced, not interpreted, but we are hard-wired to try and interpret what we see. If we weren’t, humanity would have been killed by wild beasts in its earliest days, and we wouldn’t be able to go shopping now. The relationship between the word ‘milk’, an actual bottle of milk, and the arcane symbols £1.45 and 2.272L makes life possible: we grow up connecting the things that we see, making sense of them, and making decisions accordingly.

All the images appear in front of an intense, fuchsia-coloured background, which is undoubtedly flat, and with no spatial value – although we do see it as being ‘behind’ everything else. The objects ring out against this luscious, rich colour, putting each one into a form of splendid isolation. The image of the canvas, which I mentioned earlier, is possibly the only object that requires specialist knowledge. We see the stretcher, which is a wooden frame, usually rectangular in shape (as it appears to be here, but we can’t see it all), around which the canvas is stretched and then attached with tacks or nails along the edges. Although we can see the back of the canvas – it appears to be mauve – we cannot see it wrapping round the stretcher, nor can we see any tacks. We can however see the small wedges (red in this case) which help to keep the corners at right angles and which are used to adjust expandable stretcher frames. They are called tightening keys, corner keys, or corner wedges: they were developed in the mid-18th century. The mirror is of a type you would expect to find attached to a bathroom wall. Thanks to the criss-cross structure, it can be pulled out, or pushed back, and could presumably also be swivelled – which can be important if you’re shaving and want to catch the right light, or the right side of your face. It would also be useful when applying make-up, I would have thought. I don’t remember seeing a mirror like this in Craig-Martin’s other work, but I could easily be wrong: I haven’t seen it all. However, the back of the canvas and the step ladder feature regularly in his vocabulary. In the Royal Academy’s exhibition, the ladder appears as early as 1980 in a wall drawing entitled Reading with Globe, for example – it’ll be in Monday’s talk – while the painting appears first (in this exhibition at least) in 1990, as one of the objects in Order of Appearance (we’ll see that on Monday as well).

At the bottom of the painting the belt – a subdued dark teal with a brilliant yellow buckle – is another object I’m not familiar with from the rest of his oeuvre. The yellow of the buckle – unusually close to the gold-coloured material from which a buckle could be made – links it visually to the yellow frame of the painting on the opposite side of the painting, and also to the ladder at the top right. The other objects are in some ways contained by this yellow triangle. The three larger objects are more elements in Craig-Martin’s lexicon which feature regularly, although not necessarily before today’s work was painted.

The fire extinguisher occurs fairly often. In Alphabet, a painting from 2007 – six years after today’s work – a full 26-letter alphabet is overlaid with 26 objects. It formed part of an exhibition that year entitled A is for Umbrella. The fire extinguisher is associated with the letter ‘T’ – for no particular reason – although that is not the ‘meaning’ it carries here. It had already appeared in 1996 (five years earlier than today’s painting) with very similar colours in Innocence and experience (fire extinguisher), which is illustrated above right. Its appearance in the earlier work, alongside office lockers and a pair of handcuffs, implies a dramatic situation, or novelistic encounter, which we are effectively invited to reconstruct. Given the title, which of the objects would you say represent ‘innocence’, and which ‘experience’? Is there even a distinction?

There are glasses like the ones we are looking at today, as well as another ladder, in another of the wall drawings in the exhibition, Modern Dance (1981). Here is a photo I took earlier.

The appearance of the spectacles here suggests that they are not necessarily sunglasses, whatever I may have said earlier: the glass might be colourless, but is shown red anyway, in the same way that every other colour is different from ‘normal’. Or are they meant to be rose-tinted glasses? Does that help with the interpretation of the painting? Or is it a red herring? Colour often has a powerful metaphorical value…

The pencil sharpener might not be a frequent symbol, but it does occur in the exhibition on its own at an enormous scale. The canvas on the right, Sharpener (2002), measures 289.6 x 172.7 cm.

What does it all add up to? What is the relationship between these objects? What is it that brings them together on the same canvas? We have one further piece of evidence to bring in to play, which might just help: the title. I have omitted it at the top of the post, going against my usual convention. The painting is called Las Meninas II. Las Meninas I was painted in 2000, the year before this version. It is slightly smaller, but has a very similar composition, with the same objects in slightly different sizes but with very different colours. If you’re interested in the art market, it was sold by Christie’s in 2016 for £149,000. They are both, of course, transcriptions by Michael Craig-Martin of one of the world’s greatest works of art (I’m not alone in making this assertion), Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez.

As with other aspects of Michael Craig-Martin’s work, some of the connections between the two paintings are obvious, while other objects tantalise with their tangential relationship to the original. And what seems obvious to me might result from the assumption I am making that there is a 1:1 relationship between the objects in the two works – which, as will soon become clear, there is not. However, what is undoubtedly ‘obvious’ is that both paintings show the back of a the canvas on the left hand side. There are differences, though. Velázquez’ example has three cross bars arranged up the painting, as opposed to Craig-Martin’s one. Velázquez paints the edge of the canvas wrapped around the stretcher (you’d need a bigger image to see that, though), but not any tightening keys (but then, they hadn’t been invented yet).

In the background, the Queen’s chamberlain looks out towards us from a doorway, his feet on two different steps – and I have no problem in equating the stepladder with this short staircase. To our left of him hangs a mirror, reflecting both King and Queen as they watch Velázquez create his masterpiece. Or are they standing there as models, while the artist paints their image in the mirror? Whichever it is (it is both), we stand just to their right, our point of view being equivalent to the vanishing point of the painting, which is at the chamberlain’s raised elbow. To me, the connection between the mirror in both paintings seems clear. In the original canvas, Velázquez himself peers out from behind the work in progress. In the same way, the fire extinguisher could be described as peering out from behind Craig-Martin’s canvas, with its one yellow eye, and a hose which is not entirely unlike the Spanish master’s left arm. Why Craig-Martin should depict Velázquez as a fire extinguisher is not clear, but of all the possibilities that painting provides, of all the different flames of inspiration, this is the one that Velázquez has chosen, thus extinguishing all others. He has things under control, and has contained the burning need to paint. Or maybe this is Craig-Martin himself? What would that say?

And what of the glasses, the pencil sharpener and the belt? Given that there are seven more people in Las Meninas who are not, as yet, ‘represented’, is it possible that these things can stand in for more than one person each? I don’t think it is that simplistic. These three objects can be interpreted in whatever way you will – but then, so can the other four. However, I really want the belt to stand in for the dog, sprawled across the floor in a not entirely dissimilar way. After all, it’s not unlike a collar, or lead. In a similar way (and this really is what I want it to be, what suits me and my mood now), the pencil sharpener makes me look to one of the court dwarves, Maribárbola, a little taller than the Infanta, perhaps, but a fully grown woman. I’ve always assumed that she was a redoubtable character who would take no prisoners – and probably wouldn’t take any nonsense from the young Infanta either. She would keep everyone sharp. She was also one of the court jesters, and probably had a sharp tongue too. Which leaves us the glasses.

Ah! The glasses! Probably my favourite detail. And they are my favourite because, as one object, they have to relate, somehow, to the six people we haven’t mentioned so far. Or to the paintings hanging on the walls, all of which can be identified by reference to inventories of the Royal Palace. Well, I can’t make them tie into all of this – but I’m sure they represent many different things. The interpretation of paintings is rarely ‘either/or’, but more frequently ‘maybe/and’. In this case, there are several ‘and’s. For a start, their size suggested earlier that they might be hovering in front of our eyes. Maybe they are actually standing in for our eyes, looking at the work, and trying to work out what is going on. They represent the act of looking itself, and our presence in front of the canvas.

Earlier I pointed out the implication that we are standing to the right of the King and Queen: maybe the glasses are also two royal lenses joined as one, the King and Queen, who watching the proceedings, watching Velázquez painting them watching as they are reflected in the mirror. But there are also Las Meninas, the eponymous ladies-in-waiting, standing on either side of the Infanta and watching over her, keeping a close eye, framing her so that we see her clearly, diminutive in the middle of this enormous painting. Maybe Craig-Martin has painted lenses-in-waiting, watching over a notable absence, the Infanta herself, the powerless hope for the future of the dynasty. I don’t know. But I want all of these interpretations to be true. However, I would also be very happy if you saw things differently: it depends on your point of view. Unless Michael Craig-Martin tells us exactly what he was thinking, we will never know. And I suspect he might not even have known himself: that is what makes him an artist, I suppose – or one of the many things. There are always different points of view, different ways of seeing. It depends how you focus your lens – so I’ll try and keep things focussed on Monday.

My work is simple and sophisticated at the same time….My picture of our society is that the things that unite us, at a very simple level, are the ordinary things we make to survive.

—Michael Craig-Martin