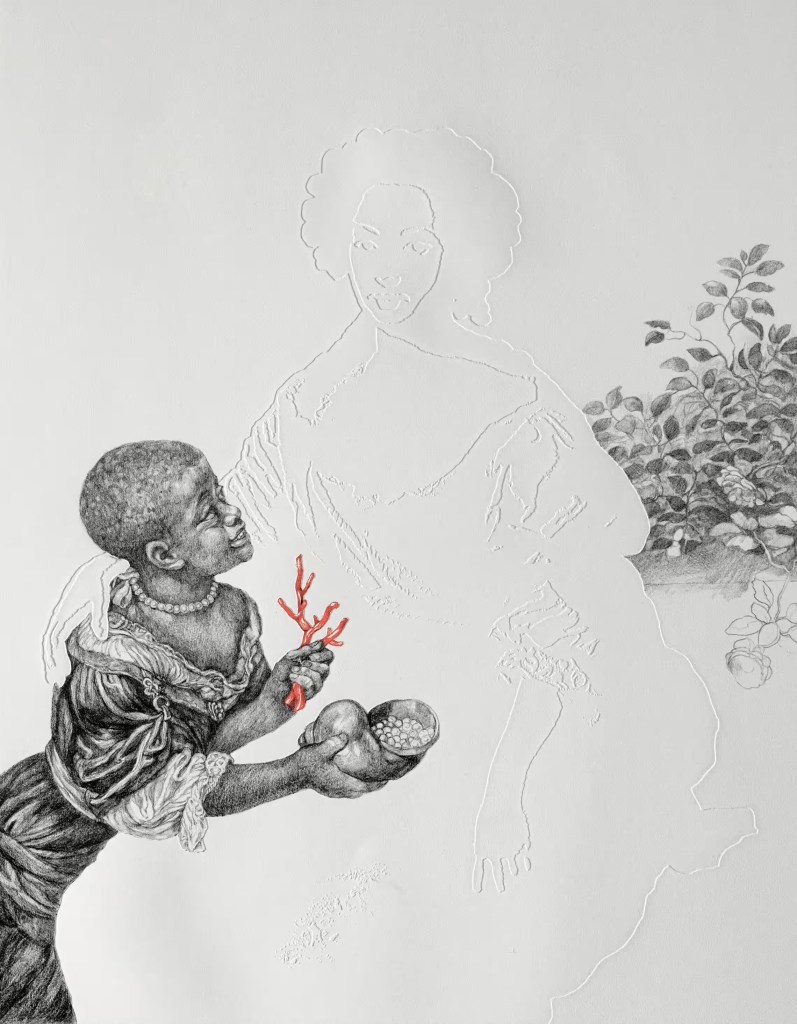

Barbara Walker, Vanishing Point 24 (Mignard), 2021. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester.

Barbara Walker is an artist I should have been aware of earlier: she has exhibited every year since she graduated from the University of Central England in 1996, and has built up a remarkable body of work, distinguished by its integrity, its compassion, and its intelligence – both emotional and intellectual – not to mention by her superb technique, which ranks among the very best. I will be talking about the first survey of her work, Barbara Walker: Being Here this Monday, 28 October at 6pm. The exhibition follows hot on the heels of her nomination for the Turner prize last year, and her election as a Royal Academician in December 2022. Although seen as a ‘retrospective’, looking back across her thirty-year career so far, Walker herself would prefer to see it differently, as she made clear in a recent interview in the Guardian: ‘It’s an introduction, so an audience can see how I’ve started … There’s so much more to say’.

After that, I’m taking a week out to see how the Ghent altarpiece is getting on, but then I will start a four-week exploration of the major offering from the Royal Academy this autumn, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c. 1504. The first two talks, focussing on Michelangelo (11 November) and Leonardo (18 November) are on sale already, with the other two coming online just after the first talk, with a discount for anyone who was there. Given this exhibition, and the forthcoming one at the King’s Gallery, there will be a considerable focus on drawing over the next few weeks, and today is no exception. Although Walker trained as a painter (and, as you will see on Monday, her technique is exceptional), she has subsequently adopted drawing as her primary focus. As she has said, “Drawing is an accessible medium that is comfortable to work with. It’s very forgiving. It’s very flexible. It’s a medium that is easy to communicate with (and through).”

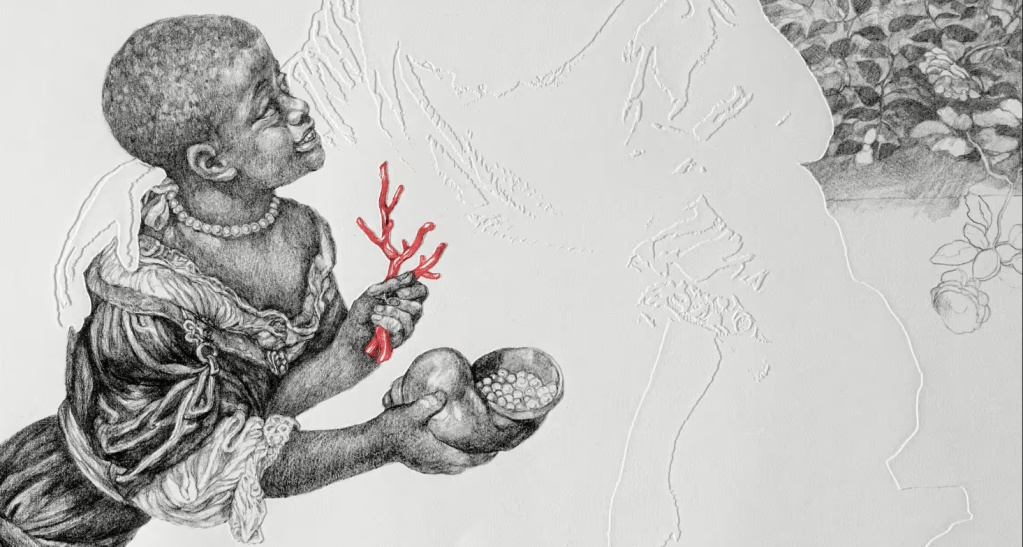

In the bottom left of a white sheet of paper, displayed in portrait format and measuring 89 x 74.6 cm – a relatively large size for a drawing – we see a detailed depiction of a girl holding some red coral and a seashell, smiling and looking up towards the top right. Her clothing is not contemporary, despite the date of this work (2021), and, given the historical dress, her hair is remarkably short. Her skirts extend to the bottom left corner of the paper, and she leans in on a diagonal which could easily form one side of a pyramidal composition. On the other side of the paper, more or less at a level with the girl’s head, are the intricately-drawn leaves of a rose bush, a couple of blooms visible, one of which is only sketched in outline. This section of drawing is marginally fainter than that of the girl, reminding us that she is the focus of interest. The two areas which are drawn serve to emphasize the void in between, an absence of form in which only a ghost remains, the seated figure of a woman with her arm around the girl. The woman’s head is at the apex of the implied pyramid, her sleeve and the outline of her dress completing its structure on the right.

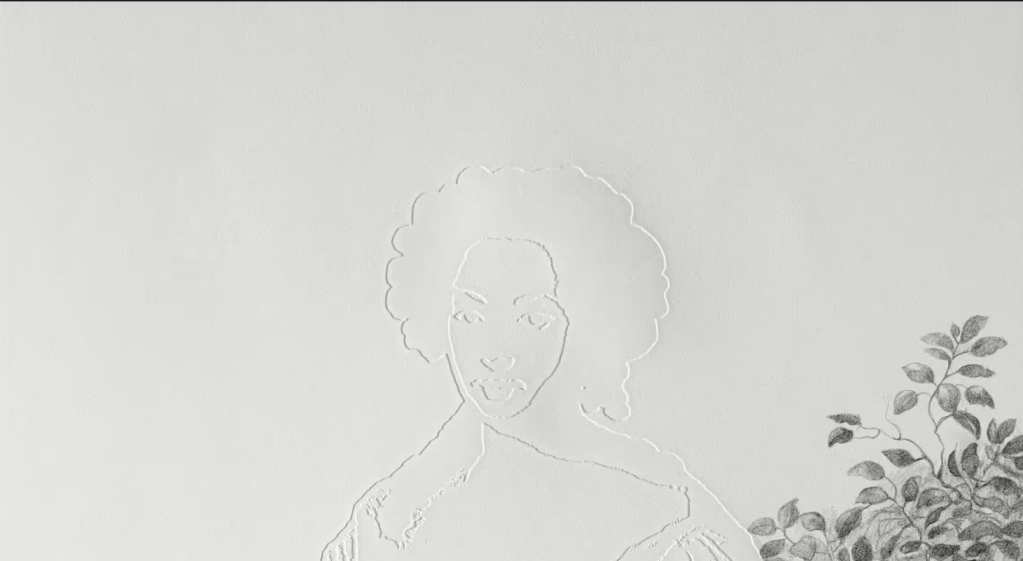

Drawing is not the only technique employed here: it is combined with a form of printing which does not use ink: blind embossing. In order to do this, rather than preparing a plate, inking it, and pressing it evenly onto the paper, two metal dies are needed. One has a raised design, effectively a low-relief sculpture, while the other has a recessed version of the same image. By pressing the paper between them the image is embossed. It works better when the paper is not thin (as thin paper might rip) and it helps if the paper is damp, to make it more flexible. In this detail the die has picked out the hair, facial features, and clothes of the subject, leaving her flesh – the face and chest – flat. And white.

The whiteness, and the lack of visibility of this person, is not exactly the point of the image: it is more relevant that we are looking at a Black girl. Walker’s intentions might initially appear to be quite simple – and yet when considered in depth they are of course complex, profound and urgent. The point is that in Old Master Paintings people of colour are rarely represented, and when they are, as here, they are seen as servants or slaves – with the exception of the occasional magus, or king. But, given that viewers tend to concentrate on the ‘main subject’ of the painting, these ‘minor’ characters have often been overlooked. Art Historians in the past have usually done exactly that, and I did too in my initial description of the image – precisely to make this point.

Walker is primarily addressing the problem of the invisibility of people of colour in Western European art, but she is also pointing out the ways in which the Black presence in these paintings has often been ignored. Her work is, as much as anything, an act of re-balancing. Inevitably it goes further than that. I spent more than two decades taking school parties around the National Gallery, and I frequently worked with classes in which children of colour formed the majority. One argument for the value of art, and why it is important for us all, is that it can reveal universal truths – and this is where the problem lies. The children were usually delighted to learn that, given that this is the British National Gallery, and they are British, the paintings belong to them. But what universal truths could I show them? What role models are there to aspire to? What function do people like them play in the universal truths of the world of art? They are servants and slaves, mainly. One musician. And the occasional king. As a whole the collection states, quite loudly, that ‘this is not about you’. Or, if it is, ‘… so now you know your place’.

Let’s take a step back, for the moment, and take another look at the technique. It is superb, using ‘Graphite and coloured pencil on embossed paper’, according to Walker’s website. The complex folds of the dark dress and the white chemise are masterfully modelled in contrasting tones of the graphite, while the coral is delicately picked out in red pencil. Notice how the embossing of the drapery is expertly handled so that it neatly frames the area on which coral and shell are drawn. Not only does it frame these attributes (in the same way that the hand on the girl’s shoulder frames her) but it also leaves a flat area on which the important details can be drawn precisely, thus making them stand out clearly. The neckline of the bodice is low-cut, while the sleeves are mid-length, and gathered in the style of the late 17th century. The girl smiles as she looks upwards, wearing a single string of pearls around her neck. There are more pearls in the shell, which functions as a cup. She is offering the ‘absent’ women the treasures of the sea, the unrecognised, and unacknowledged irony being that she too is one of those ‘treasures’ – an African slave, traded across the sea and bringing great wealth. In classical mythology, coral formed after Perseus slew Medusa, and drops of the Gorgon’s blood petrified the seaweed and turned it red. It is not this girl who has blood on her hands, though.

Walker’s work is a version of a painting by Pierre Mignard which is in the National Portrait Gallery in London, Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth with an unknown female attendant (1682). Kéroualle was French, and first came to England in 1670 as a maid of honour to Henrietta Anne, the sister of Charles II, who had grown up in France during the Commonwealth and married the Duke of Orleans. After this visit, Kéroualle returned to England in 1671, but this time as the King’s mistress: the French government was hoping it would make sense, diplomatically. She bore the king one son, and had some sway in court, but she wasn’t popular overall: neither her nationality, nor her position went down well – nor did her religion. Nell Gynn stigmatised her as Charles II’s ‘catholic whore’. The portrait was painted from life during a visit to Paris in 1682, nine years after Charles had made her, his mistress, Duchess of Portsmouth. It could be that her association with one of England’s major ports led Mignard to identify her as the sea nymph Thetis, one of the daughters of Neptune, and mother of Achilles: although there is nothing classicizing in the way she is depicted, we can at least see the sea in the background, and coral and pearls are relevant attributes. The National Gallery also has a portrait by Mignard, The Marquise de Seignelay and Two of her Sons. The late husband of the Marquise had been Secretary of State for the Navy in France, and in her portrait she too is identified as Thetis. One of her sons is dressed as Achilles, while another is cupid, wings and all, and like Kéroualle’s ‘maid’, he also bears an offering of coral and pearls in a seashell.

The fact is, we know a lot about Louise de Kéroualle, and about Mignard for that matter, but we know nothing about this girl. For the aristocracy servants were a fact of life, but it became fashionable to own Black slaves, who took the place of the servants. Pearls were highly prized for their rarity, and for their purity of shape and colour, which were seen as equivalents to the perfection and pallor of the complexions of the ruling classes. The slaves likewise functioned as an indicator of the wealth of their owners, but, unlike the pearls, they were used as a contrast, a foil to the prized pale skin. We do not know this girl’s name, nor for that matter, if this image is based on a real person: she could be just an imaginary ‘prop’, put there to heighten her supposed mistresses skin tones and to make her look richer. Real or imaginary, I’m not sure which is worse. ‘Real’, of course, but ‘imaginary’ speaks of the same inhumanity.

This is just one of a series of works given the overall title Vanishing Point. Taking its name, of course, from the standard perspectival construction, it plays on the idea of looking at things from a different perspective, while also considering the ways in which people of colour have ‘vanished’ from the history of art. Walker gives pride of place to these anonymous and often overlooked subjects in order to reclaim their lives and their dignity, and, in some way, to counter the historical injustice. As she herself has said in an interview for Art UK, ‘The girl is a possession, but she’s got this stoic look. It’s emotionally and psychologically disturbing, but as I draw, I imagine that I’m extracting and saving her.’ This is Vanishing Point 24 (Mignard), which is now part of the superb collection of 20th century works on paper by British artists at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. It is not, as it happens, in the exhibition at The Whitworth about which I will be speaking on Monday – but eleven others from the series are, a selection from just one of the ‘chapters’ in Walker’s work. So far there are 50 images in the Vanishing Point series, but it is ongoing – there will be more. For some artists individual works are best seen on their own, but for Barbara Walker’s work, seeing the images together is incredibly telling. With each repetition of what might seem like the same idea, but in a different form, the extent of marginalisation, of distancing, of covering up, of passing over and then forgetting becomes more obvious and more vital. This applies equally to each of the other ‘chapters’ into which her output can be divided, all of which are represented at The Whitworth: there’s so much more to say.

fantastic artist who exhibited as part of Fitzwilliam’ essay approach earlier in the year. The Higgins in Bedford had a similar but different approach through Peter Braithwaites work. He is having a conversation with the curator at The Higgins later in November.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Margaret – I was annoyed that I missed the Fitzwilliam exhibition… and I confess I hadn’t even heard of The Higgins: so many museums, so little time! But thanks for letting me know about the Peter Braithwaite exhibition. The great thing (for me) about Barbara Walker at The Whitworth is that it’s not too far away from me in Merseyside!

LikeLike

I really loved your thoughts

LikeLiked by 1 person