As I said on Monday, when talking about Michelangelo, the Royal Academy’s Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c. 1504 constitutes, for me, the perfect exhibition. It is beautifully focussed, with great art, all of which has a reason for being there, and it elucidates with clarity a small moment in the History of Art which had an enormous impact. I will continue my exploration this Monday, 18 November at 6pm by looking in detail at the works of Leonardo da Vinci which are on display, putting them into the context of his career up to this date. By doing this for all three artists I am hoping that, by the time we get to week 4 (1504, 2 December) all of the connections between the three protagonists and the art of their time will fall neatly into place. By then, though, we will also have had the chance to see the masterful drawings and paintings by Raphael (25 November) in the exhibition – and which are so brilliantly hung that the relationship between the works and the interactions of the artists are clear to see. Details of these talks, and the first few of Artemisia’s tours for next year, are now on the diary (apologies if you looked last week: somehow my edits didn’t upload…)

No one has ever thought about saving the pieces of paper that sit on my desk, where I take notes and make the occasional doodle, and were you to see them you would know why. Thankfully, however, so many of Leonardo’s musings, doodles and scribbles have been saved – and they really are the feature of his output that makes him so truly fascinating. Having said that, I find people’s attitude to art can be surprisingly contradictory. So many people dismiss ‘modern’ art out of hand for its lack of ‘skill’ or ‘finish’ without even stopping to think about what they are looking at (or rather, what they have not even bothered to look at). On the other hand, we are drawn to a mess like this – an untidy page of preparatory scrawls which were never meant to be seen, covering two different ideas at least. The other side of the paper has nothing to do with art at all, although the insistent ideas seep through the page to confuse the appearance of the drawings we really want to look at.

Where does the fascination lie? Of course, even among the untidy mess, Leonardo’s innate talent remains unquestioned. I’m not sure that there is enough on this one piece of paper to qualify him as a ‘genius’, though – but we probably all realise that this page is just one of the facets of his remarkable creativity, all of which are expressions of his agile mind, which together add up to nothing less – genius. But is it ‘art’?

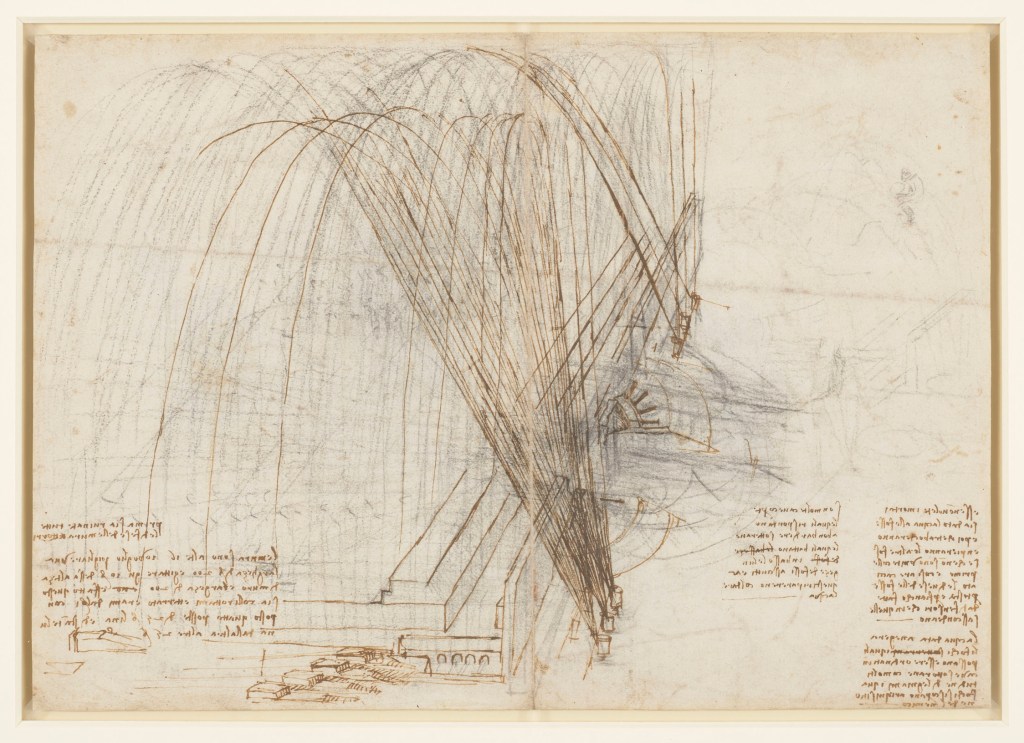

As far as I am concerned there are four main areas of interest on this page, which is catalogued in the Royal Collection as RCIN 912337r. The ‘r’ stands for ‘recto’, meaning it is the right way round, or, in other words, that this is the front of the paper. We will see the back (or ‘verso’ – ‘v’) later. Calling this ‘recto’ implies that this is where Leonardo started – or it could be that, when it was catalogued, this side was considered to be more important – probably because it has the artistic ideas. The four sections I am interested in show a rearing horse, at the top of the paper just to the right of centre, and then three sketches, unconnected to the horse, which all explore the same idea. They are lined up on a diagonal going from half way up the paper on the left, to the bottom of the page to the right of centre. However, I doubt this was the order in which the three sketches were drawn. I will start with the horse.

Standing on its hind legs, the horse rears up to our left. Leonardo has settled on the form of its torso, which is firmly outlined in a sharpened black chalk, with softer, broader strokes merging together to model its haunches, belly, flanks and shoulder (I know nothing about horses, but the Wikipedia entry on Equine anatomy might help). However, there is much for him still to decide – and that is the purpose of this drawing. While the position of the near hind leg (i.e. the left one, apparently) is fixed, the far one is shown in two different places – both further back and further forward than the left, with the former variation being sketched in at least two slightly different positions. The forelegs are not subject to this variation, but the far leg is only faintly delineated. Nevertheless, their position seems secure, even if they were not deemed important enough for the purposes of this study to draw them more strongly. Alternatively, it could be that the far foreleg is fainter in order to remind us that it is further away. The tail is only hinted at, with faint lines suggesting potential positions for its top and bottom. The same is true of the head: the position is apparently fixed, and it even has a slight tilt to the horse’s right, but Leonardo was not interested in the detail (there are other drawings which cover that). If you look just below the horse’s head – at the top of the neck – you may be able to pick out something else: the head of a rider, with the profile and a mop of hair sketched in, and an eye clearly marked with a couple of dark stabs of the chalk. This is Piergiampaolo Orsini, a captain of the Florentine army, and the drawing is related to Leonardo’s planned mural of The Battle of Anghiari – but as I will discuss that in detail on Monday I won’t go into it now. The sketched outline of Orsini’s back can be seen curving up from the horse’s, with the human shoulder just to the right of the equine neck. Orsini’s right arm is bent, and held behind him, while the left reaches down in front of the horse’s shoulder. Leonardo has decided how the rider will be sitting, but in this drawing he is still focussing on the precise forms of the horse. The writing, and scrawled, almost-parallel lines you can see around the horse are actually on the other side of the paper, so let’s not worry about them now. Instead, we will think about the gradual development of an idea which is completely unrelated to The Battle of Anghiari.

This is the faintest of the three sketches, the one towards the bottom of the page just to the right of centre. It looks as if it has been crossed out, but the rusty-looking diagonal lines which pass through it are the result of the iron gall ink seeping through from the other side of the paper. Although only a whisp of an idea, it is still possible to make out the form: a human figure kneeling on its right leg, the left knee bent, with the foot planted on the ground. The hips face outwards on a diagonal to our left, while the shoulders are twisted the other way, with the chest facing out and to our right. The head is tilted to one side, and the right arm crosses the torso. Together with the left arm, it gestures behind the figure. A small oval may indicate another form, and a curve to the right of the neck might imply another, lower position for the head, potentially looking at whatever the oval represents. There is also something else above the figure, to the left. At the bottom of this detail a line is marked with equally spaced dashes, which might allow for the sketch to be scaled up – although looking at the page as a whole, this scale appears to relate to a different idea, which is difficult to interpret.

The image on the far left – here seen at the same scale as the first – has been far more thoroughly worked. It is impossible to tell which of the two sketches came first, but this one clearly triggered more ideas than the one we have already seen. The drawing looks rather frantic, as if the figure is scrabbling around, trying to settle – and in a way, that is what Leonardo’s mind and hand are doing: scrabbling around, trying to settle on the right form – the best form – for this particular idea. This is a technique he would have learnt in the studio of Verrocchio: drawing different possibilities for the same image on the same piece of paper, gradually focussing in on the one that is most of interest (again, I will talk about this more on Monday).

Eventually the effect can become confusing, and there were at least two means of clarification. The first was to transfer the best idea – the most interesting lines – to a new piece of paper, either by putting the first drawing over a blank sheet and drawing over the lines you want to keep with a stylus, pressing hard, thus creating an indented but colourless line on both pieces of paper. Alternatively, you could prick the outlines on the top sheet with a pin: the holes in the blank piece of paper underneath would be enough to sketch the outline. Here, though, rather than transferring the drawing to a fresh page, he has decided to clarify the outlines with pen and ink – the only problem being that the idea has so much potential there are yet more confusing possibilities in ink. Nevertheless, what we are looking at is basically the same idea as in the first sketch. More obviously than before, it is a female figure: the breasts are clearly marked (and if you know where the drawing is going they are just visible in the previous sketch). She is still kneeling on her right knee and turning to her left, and has various other features drawn around her, although it is still not clear what they are. In the black chalk I can see at least four possible positions for the head, with a fifth picked out in ink, probably over a black chalk original. Leonardo has decided to focus his attention on a particular area of the composition, and has sketched a rectangular framing element in ink: this is the part of the drawing that he is interested in, leaving some of the roundish forms to the bottom left of this detail out of the picture – quite literally.

The same composition is repeated in the third sketch – the one in the middle of the three – which is also shown at the same scale here. Again there is a mass of chalk marks, which, if anything, are even vaguer, but the pen and ink outline settles the composition firmly and with greater clarity than before. As in the first sketch we can see that both arms reach back to another figure, a small child, or even baby – the circle with a line across it can be read as having two eyes, a nose and a mouth. There are two hemispherical forms below it. Other elements of the chalk drawing – a mad mass of hair, and undefined details to the left and right – have not been picked out in pen. To follow the idea further we have to switch to another drawing, dated c. 1505-07, in the Devonshire Collection at Chatsworth House.

The idea has evolved: there will have been other drawings we haven’t seen, and which may not have survived. Although she is still kneeling on her right knee, with the left knee raised, the woman is no longer turning to her left – thus taking out the twist in her torso. Instead, she faces towards us, her head tilted to one side, and she gestures towards not one, but four babies, all wriggling on the ground. Near them are a number of rounded forms, the development of the two hemispheres I mentioned above. The babies have just hatched from eggs, obviously… Well, it is obvious if you know the story, and realise that we are in the world of classical mythology where anything is possible. In addition, a new character has been introduced: a swan stands next to the woman, its left wing folded, its right protectively – or possessively – round her shoulders. It whispers sweet nothings into her ear – or nibbles her hair as if it were pond weed. This is, of course, Jupiter, King of the Gods, who has transformed himself into a swan in order to seduce Leda. The end result – pregnancy, inevitably – was followed by the safe delivery of two eggs. Each egg hatched a pair of twins. Castor and Pollux were in one. Associated with horses and war, they brought news of victory and defeat, as well as saving those in trouble at sea or danger in war. The other egg hatched to reveal Helen of Sparta – the most beautiful woman in the world, better known as Helen of Troy – and Clytemnestra, who murdered her husband Agamemnon because he had sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia… It’s a long story, and even telling in at greater length might not clarify the twins’ paternity. Let’s just focus on the drawing. It was one of two versions of Leda which Leonardo developed, but no paintings by him of the subject are known. He doesn’t seem to have painted this composition – but other people did.

This version is in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Kassel (central Germany). It was painted by an artist known as Giampetrino (probably Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, but it’s not certain), who was active between 1495 and 1549, and a member of Leonardo’s circle in Milan. The idea is different again – so again there must have been more drawings. The swan is gone, and the twins are distributed on either side of Leda, with one of them held in her right arm. Raphael did paint a version of the other composition, although it hasn’t been seen since 1625, and may have been destroyed deliberately. I am hoping to write about it next week, but it looks like I’ll run out of time… However, I will eventually show you Raphael’s drawing of it – but not on Monday, when I will be focussing on Leonardo.

Oh, of course – I was going to show the other side of the drawing – the verso. Here Leonardo focusses on warfare, an expertise he had stressed when applying to work at the court in Milan back in 1482. The drawing has been given the title Mortars bombarding a fortress, and RCIN 912337v shows just that, with an all-out assault over the walls from mortars stationed just outside the building. Leonardo sketches the parabolic trajectory of the missiles with apparent ease, with explanations provided by neat, ordered notes in his idiosyncratic mirror writing: contained, controlled, inhuman. I’ll stick to the other side – even if the implications are inconceivable…

Dear Dr Stemp,

This is sort of related to your blog.

I always note with interest the topics of your lectures + wish that I lived in England so that I could listen to them.

I enjoy your blog as I did your book on the Renaissance.

I note that your lectures are not recorded. Have you thought of recording them + making them available for a fee.

In that way, despite the fact that I live in Australia, I could enjoy listening to you.

With kind regards – Paula

Paula Nathan, AO

paulanathan1@outlook.com

LikeLike

Hi Richard,

you are on fine form with your blogs, superb!

I’ve been meaning to check in with you for a while! How is everything going with you? Are you and Wayne still based in Liverpool? How is everything there? Are you still mainly working online?

Main reason to write is to send love to you lovely man.

All love and good wishes,

Marc

Marc Woodhead

http://www.marcwoodhead.com http://www.marcwoodhead.com/

>

LikeLike

Thank you, Marc – a fuller reply on its way elsewhere!

LikeLike