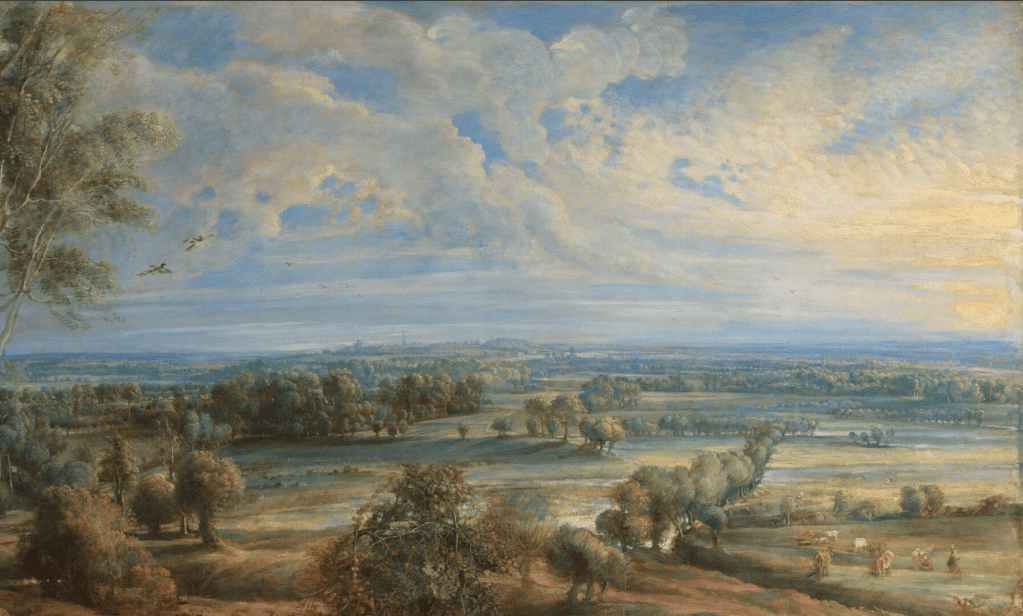

Peter Paul Rubens, A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning, probably 1636. The National Gallery, London.

After five weeks talking about the Italian Renaissance I’m going to take a break and head forward to the 19th Century. There is a direct line to be drawn, I think, from Constable, via Monet, to Van Gogh – and as all three have exhibitions in London at the moment, it makes sense to draw the line somewhere… I started with Van Gogh, soon after that exhibition opened, back in October, and this Monday 16 December I will go back (in art historical time) to Discover Constable & The Hay Wain – an exhibition which sets out to clarify how radical the oh-so-familiar nostalgia-infused painting actually was. I’m not entirely convinced that the curators succeed in this aim, but that doesn’t stop it being a great painting, or a good exhibition. Like others in the relatively recent Discover series, it focusses on the titular painting, enlarging our knowledge and understanding of the work, and giving us a better sense of its relevance for the world in which it was created. The following week, 23 December, I will creep into the 20th Century, which is when the particular views The Courtauld are celebrating were painted. If you haven’t seen or booked for Monet and London: Views of the Thames, it is a jewel of an exhibition, but I’m afraid the whole run is now sold out – so maybe the talk would be your best chance to see something of it. I will return to the Renaissance with renewed energy in the New Year, looking first at The Virgin and Child (a brief history) on 6 January. Next is another small exhibition at back the National Gallery, Parmigianino: The Vision of Saint Jerome on 13 January. I’m planning to follow that by exploring Women Patrons in the Renaissance before asking What is Mannerism? All of this will gradually make its way on to the diary, of course. Meanwhile, to get us from the Renaissance to Romanticism I want to stop off in the 17th Century. Whether this is Baroque or not I will let you decide for yourselves.

We are looking at a landscape. A cart, enhanced with posts and slats so that it can carry more, splashes through shallow water as it is pulled by horses on a diagonal to our left. In addition to the horses there are two people. At the far left there is a house among the trees, with smoke coming from one of the chimneys. The trees fill a lot of the top left corner of the painting, although there is a clouded sky visible above them. The top right corner is given over to an expanse of open sky, with clouds lit by the sun. A man in the undergrowth is out looking for something to eat – if he can lay his hands on it – and beyond the fields stretch out into the distance.

I say, ‘we are looking at a landscape’ – but not the same one. I was actually looking at Constable’s The Hay Wain – but I’m assuming that you will have followed my description while looking at the picture I’ve posted of Rubens’ Het Steen. I’ll come back to this connection later – but first we should get to know the Rubens better (and of course I will spend more time with the Constable on Monday).

Het Steen can be translated, literally, as ‘the stone’, although it effectively means ‘the fortress’. It is the title of the large manor house at the top left of the painting. Rubens purchased it in 1635, thanks to his enormous wealth – the result of his successful career – and to the status which came from being knighted by both Philip IV of Spain and Charles I of England and Scotland. A person of lower rank would not have been allowed to buy such a grand building, and anyone with less money would not have been able to afford it. At the age of 58 Rubens was effectively retiring to the countryside, leaving behind a life of diplomacy and large scale public commissions in order to paint a few portraits and more landscapes – many of which, like this one, were done for his own pleasure. His grand new home bristles with battlements and is complete with a moat. Access to the front door is across a small bridge, from which a man can be seen fishing. Sunlight flashes off the windows, and a group of the nobility (among whom Rubens could count himself) are gathered outside. My guess is that they have been up all night. At the bottom of this detail a woman in a straw hat and red jacket can be seen.

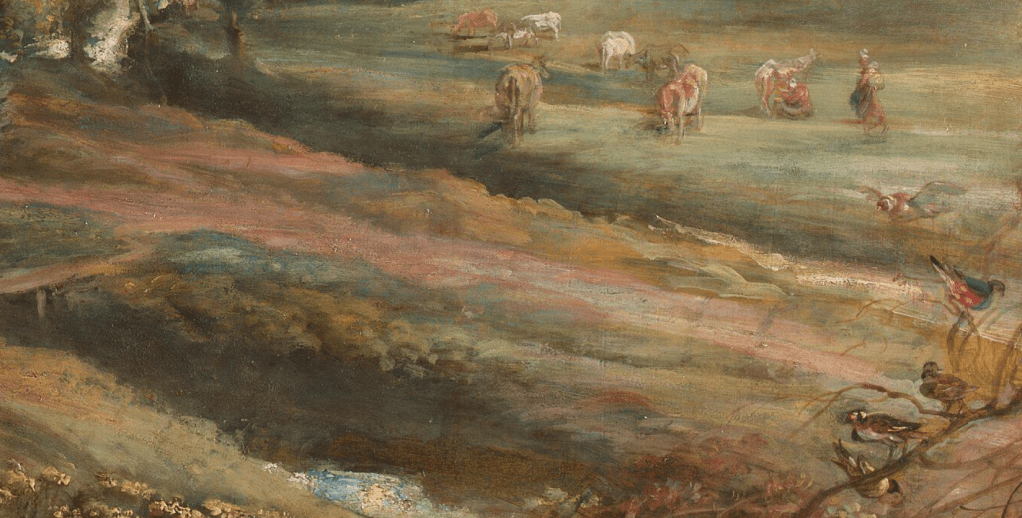

She is the only person riding on the cart. As well as the red jacket she wears a blue skirt, and looped around her left elbow is a cord tied around a large copper jug – which I suspect contains milk. This rests on a barrel, in which there may be more milk (was milk ever kept in barrels?) – although it might contain beer. There is also a calf with bound legs lying on some straw, suggesting that this couple is heading of to sell the rich produce of Flanders at the nearest market. The cart is pulled by two yoked horses, which are steered and driven forward by a man riding the nearer of the two. He holds the reins with both hands, and also clasps a whip in his right. The white splashes of paint which streak back from the horses’ feet and from the wheels of the cart tell us that they are making their way through shallow water – a ford, or, more likely, a sizeable puddle in the dirt track leading away from the manor house.

Further to the right a man is hunting for his dinner… or something to sell. He crouches down, gun in hand, accompanied by a dog. He is hiding from some ducks in the adjacent field, clearly hoping to pot one or two of them, providing that they don’t all fly away at the first shot. He hides behind the hollow trunk of a blasted tree whose lower branches have survived and spread both left and right. This is just the first element in some form of hedge, which develops into a line of trees that stretches along a diagonal to the top right corner of this detail. The huntsman’s right leg, stretched out behind him, forms the beginning of this diagonal which is continued by his back. His gaze also leads our eyes into the distance. He could almost be the definition of the word repoussoir, pushing our eyes back into the depth of the painting. A brook cuts between the trees just beyond the ducks, but there is a precarious plank bridge crossing it. As with so many landscapes, we are invited to travel through this space in our imaginations, and both the obstructions to our journey, and the way to overcome them, are shown. If the trees – and the poacher’s gaze – lead our eye to the top right, the brook could distract us to look towards the top left. The curving, flooded track along which the cart is trundling follows parallel to the poacher’s back, then later curves round to the left, where it echoes the line of the brook before disappearing out of sight. We can still see where it is, though, as its route is measured out by the bases of the trees growing on the adjacent bank.

The line of trees – the continuation of the diagonal which starts at the huntsman’s right foot – gradually diminishes until it is terminated by another row parallel to the horizon – although that doesn’t stop our eye from following the now virtual line to the sun, glowing above the horizon. The painting of the sky is one of the true glories of this landscape, with areas of clear blue interspersed with the puffs and swirls and eddies of white clouds coloured yellow by the sun, with even, I want to believe, a slight blush of pink – although that might just be my imagination. The distant horizon is blue, as if the sky has got in its way. Rubens’ control of atmospheric perspective – the effect that the atmosphere has on the way we see objects at a distance – is nowhere more subtle.

A small city can be seen on the horizon, a church tower standing tall: the distance implies that this would be a mighty structure if seen up close. There is also a small town closer to us, and a little to the right, whose buildings also look blue to the eye. I’ve never been clear if these are real places. Het Steen is 16km north-east of Brussels, and 9km due south of Mechelen. Apparently you can see the horizon 9km away if you are at a height of 6 metres above ground – and so maybe this is, indeed, Mechelen: that is certainly what I have always assumed. Rubens could have been at this height looking out of one of the top windows of the mansion, or if he had climbed the tower which is visible just behind the right end of the house. This serves to point out a basic fact about the landscape: it has a very high, and presumably imaginary, viewpoint – there were no other large structures near by. It is a format sometimes known as a ‘world landscape’, from the German ‘weltlandschaft’ – because it allows you to see so much of the world. For Rubens, it served to show how far away from the common throng he now was – and how much land he had acquired. He also painted the view looking in the opposite direction in the Rainbow Landscape, which belongs to the Wallace Collection. I’ve always wondered which market the couple on the cart are going to. My instinct is that they are heading in the direction of Brussels – but that’s a long way to go in a cart.

We could tell that the sun is close to the horizon, even if it weren’t in the painting. The trees cast long shadows across the ground, telling us that the sun must be low, and they are lit from the side with a yellowish light. If there sun were higher they would just look green. But how can we tell that it is morning rather than evening? Sunrise rather than sunset? Yes, of course I trust the National Gallery and its titles implicitly (that’s not actually true, I’m afraid… too many titles are ‘traditional’ and unrelated to the artist’s intentions), but if that is Mechelen, then we are looking towards the north and the sun must therefore be rising, as it is in the east. Not only that, but markets took place from the early morning and were usually wrapped up by lunch time. As I said earlier, I suspect that the nobility by the mansion have been up all night, whereas the poacher has tried to get up before anyone else so as not to be seen. Not that I know anything about poaching. There is also the activity of the workers in the fields to bear in mind.

Towards the right edge of the painting, we can see birds gathering on the scrubby bushes in the foreground. One goldfinch flies in with wings spread, while another stands on a branch next to what looks a bit like a blackcap. There I also something coloured, but not shaped, like a kingfisher – so I’m not sure what that is. However, above them (in pictorial terms – actually some distance away in the adjacent field) there are some cows. There are also two humans. One is walking from right to left towards the herd, while another is seated beside one of the cows: she is milking. I once asked a group of school children what time of day you milked cows, and they looked at me baffled. I thought to myself, ‘Ah, they might not even be aware of the origin of milk, as it so obviously comes from plastic bottles in the supermarket’. So I carried on, as was my habit with this painting, ‘Well, it’s something that farmer’s always do first thing in the morning’. At which point they looked even more baffled, and even alarmed. Then several of them blurted out ‘but you’ve got to do it in the afternoon as well’ – at which point I remembered that they had come from a village school, and many of them must have grown up on a farm… They were initially baffled because surely everyone knew when you were supposed to milk cows. Of course, I knew it was something that was done in the early morning because I used to listen to The Archers. All this aside, I’m sure Rubens was using it as a typical, early morning activity.

The colour in the painting is quite remarkable, and serves so many different functions. Primarily it is descriptive, of course. Grass is green, the sky is blue, and jackets can be red, for example. But it also gives us a sense of the time of year: the leaves are both green and brown, so it is presumably late summer/early autumn, before all the leaves have changed or fallen. As well as the time of the year, there is also the time of day. Even without the sun the clouds and the sides of the trees are lit yellow… And then, it gives us a sense of distance – using the standard formula developed as early as the late 15th century that the foreground should be brown, the middle-ground green, and the distance blue, thus conforming to the conventions for depicting atmospheric perspective, which are employed in this painting, as I have said, at their most subtle and organic. This was one of the formulae of art that Constable rebelled against.

But what of the relationship between Het Steen and The Hay Wain? Is it coincidence that, apart from anything else, the woman on the cart in Het Steen wears red, the same colour as the saddles of the horses pulling The Hay Wain? This is yet another function of colour: the touches of red make the green of the landscape look more green – a trick which Constable learnt from Rubens as much as from anyone else. It just helps to make the landscape look fresher. But then, Constable admired 17th century landscapes generally – both Dutch and Flemish. This wasn’t the only connection, though. Het Steen entered the National Gallery as part of the Sir George Beaumont Gift, officially dated to 1823/8. Beaumont’s promise to leave his collection to the Nation in 1823 precipitated the foundation of The National Gallery 200 years ago. He died four years later, in 1827, which is why the gift didn’t materialise until 1828. As well as being a collector and amateur artist, Beaumont was also a great patron, and even mentor, of John Constable. As a result, the artist had frequent access to his collection, and would have known Het Steen well. His painting The Cornfield (which is also in the Discover exhibition which I will discuss on Monday) is based on another of Beaumont’s paintings, Claude’s Landscape with Hagar and the Angel. Constable even carried out ‘restoration’ work for Beaumont – and it has even been suggested that some of the clouds in Canaletto’s Stonemason’s Yard were actually painting by the British artist… but that’s another story. Whether Constable was consciously basing the composition and activities of The Hay Wain on Het Steen, or if it was the subconscious result of his through knowledge of the Flemish painting and his understanding of its composition, we will probably never know. But it is almost pure luck that they have ended up in the same collection, allowing us to see the relationship at first hand.