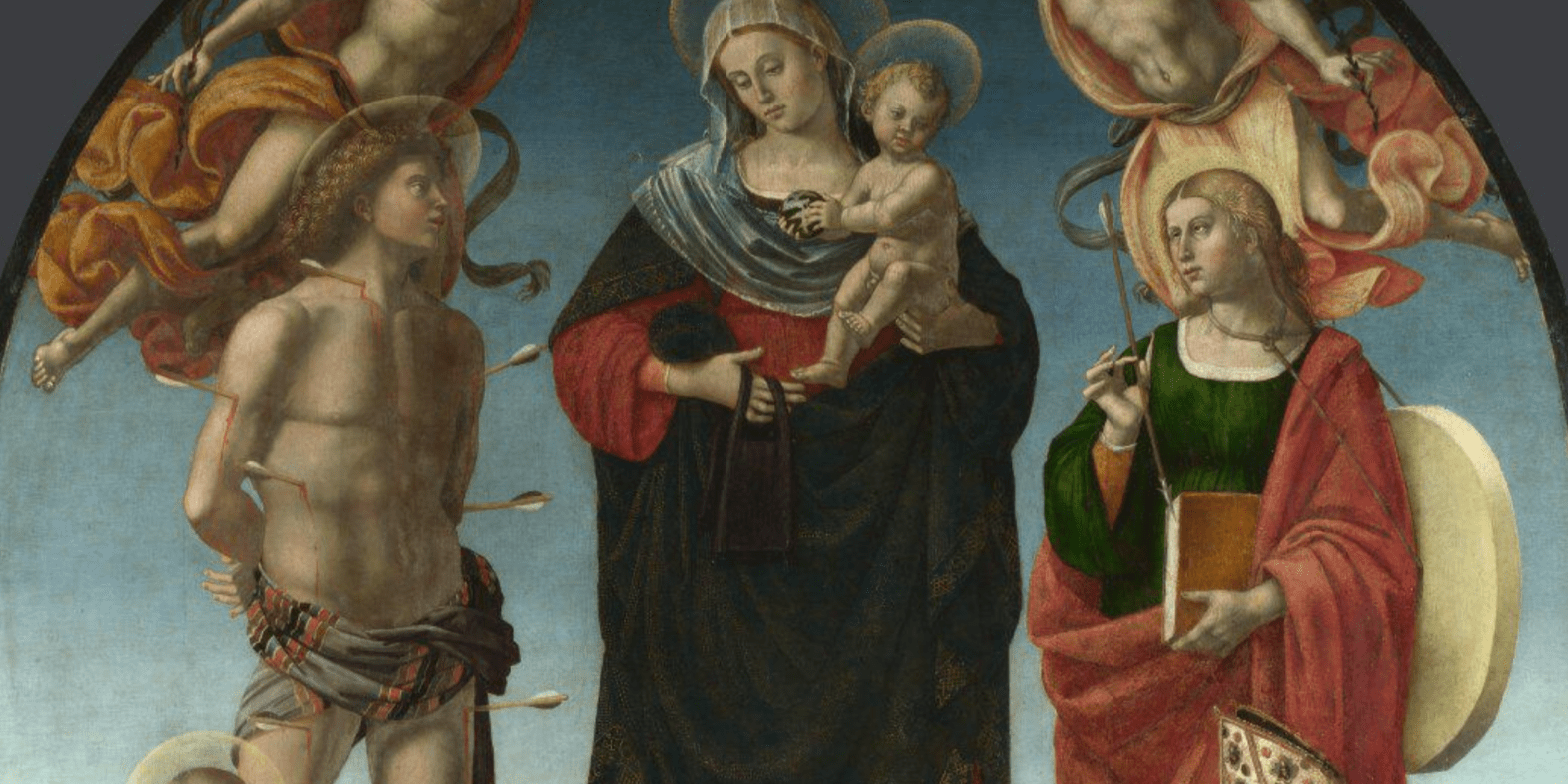

Luca Signorelli, Virgin and Child with Saints, 1515. The National Gallery, London.

This Monday, 13 January I will be talking about the National Gallery’s superb, small-scale exhibition Parmigianino: The Vision of Saint Jerome, expanding on what is on display with reference to the superb and thoroughly researched catalogue. Earlier this week, while talking about the history of images of The Virgin and Child, I briefly mentioned how the format of a painting has an effect on its composition. While I was trying hard not to discuss every illustration in detail (and apologies to those of you whose questions I did not have time to answer) I made the mistake of trying to identify all the saints in an altarpiece in the National Gallery which I don’t know very well – and failed. Thank you to all those of you who ventured valid suggestions, but it turns out to have been a saint I don’t remember having heard of before: Christina of Bolsena. This has prompted me to get to know the painting better today – giving a few hints as to its relevance for the Parmigianino on Monday. The following week (20 January) I will pick up on the style of The Vision of Saint Jerome by asking the question What is Mannerism? and on 27 January I will pick up on its patronage by taking a closer look at Women as Patrons in the Renaissance. I’m fairly sure that the week after I will talk about the origins and implications of the Sack of Rome – which is directly relevant to Parmigianino and his masterpiece – but I might change my mind: keep an eye on the diary!

Today’s altarpiece was painted by Luca Signorelli, and is of a format which became popular in the second half of the 15th century – the pala, which is a single, large painting on a unified field, and therefore different from a polyptych, an altarpiece made up of many different panels, each surrounded by a framing element. The name is derived from the Latin word for ‘cloak’, pallium, and is related to the various fabric drapes with which altars were adorned at different points in the church’s history. The simplest description of the subject matter of Signorelli’s painting would be ‘The Virgin and Child with Saints’ – like so many others – but the 16th century became increasingly inventive with the distribution of the figures across the pictorial field. One of the reasons behind this can be explained by comparing Signorelli’s pala with one of my all-time favourites, Bellini’s San Zaccaria Altarpiece, which is still in the eponymous church for which is was painted.

Both show the Virgin and Child with four saints, and both are examples of renaissance naturalism. While Signorelli locates his figures in the countryside, Bellini’s stand in a form of projecting loggia, roofed, but open to the air on either side. Our eye-level, as defined by the horizon, is about one third of the way up the painting in each, and both altarpieces have saints at far left and right standing on the ground. Indeed, all of Bellini’s saints are at the bottom of the painting, with the Madonna and Child enthroned in the middle, the throne raised on several steps, with the horizon (our eye level) coinciding with the position of Mary’s feet: we look up to her. Nevertheless, the top half of the painting is occupied by architecture, with little or no narrative or religious content. This is nevertheless an important aspect of the painting. Seen in situ, the frame of the altarpiece has the same architecture as that depicted in the painting: the arches you can see receding to the back wall theoretically spring from the entablature which also supports the arch of the frame. It makes it look as if the sacra conversazione (‘holy conversation’) is taking place in a chapel built out from the church, implying that we are in an adjoining space. It helps to make the characters look more real and immediate, thus making it more easy for us to believe in them. However, arranging them like this does limit the scale of the figures: Bellini has to fit five human figures across the width of the painting with the result that they take up about two fifths of its height (40%).

Signorelli, on the other hand, does not have all of his figures standing on the ground. Two do, and another two are poised on clouds, framing the Madonna, who is also seen in the sky. As a result, the figures can be broader, and, keeping them in proportion, also taller: they occupy about half the height of the painting (50%). Signorelli was not the only artist to do this. One result of the use of perspective – whether it is the linear, single vanishing point version employed by Bellini, or the atmospheric version out in the countryside of Signorelli – is that people, restricted to the ground, will leave the top of a portrait-format painting empty. By accepting that holy figures are not necessarily earthbound, artists could either make the saints bigger or include more of them. Parmigianino was given a more extreme challenge when commissioned to paint an altarpiece which was not only tall (nearly 3.5 m), but also relatively narrow (1.5m) – and we’ll see how he dealt with that on Monday. But how does Signorelli resolve the challenges of his commission?

Two of the saints stand on the ground, as we have said. On the left is St Jerome – there is no lion, I know, but he is dressed (anachronistically, as it happens) as a cardinal, with a long, red, hooded robe and a book resting open on his right hand. There is also a piece of paper in his left. He was known as a scholar, the translator of the bible from its various languages into what became known as the Vulgate, and the author of many essays as well as a regular correspondent – as a cardinal with a book and (probably) a letter, we don’t need to doubt that this is him. On the other side is a bishop. He is wearing a mitre (a hat with two points, effectively) and a cope (a large cloak) which is clasped below the neck with a morse. He carries a crozier, derived from a shepherd’s crook, which symbolises his care for his flock. He also carries a book, presumably also the bible, which does not necessarily help us to identify which bishop saint this is.

However, at his feet are three gold balls, representing the gold which St Nicholas of Bari threw through the window of an impoverished nobleman’s house as each of his three daughters reached marriageable age. This provided them with dowry, allowing them a respectable marriage, and meant that they would not have to resort to prostitution. St Nicholas, of course, eventually became Santa Claus, who is also associated with gift giving… To the left of this detail we see St Jerome’s broad-brimmed red cardinal’s hat, complete with its long tassels. Seen in this detail, it is more obvious that Signorelli has made the hem of his red cloak, falling across the ground, echo the disc-like form of the hat. In between these two attributes is a lengthy inscription, telling us, roughly speaking, that,

The outstanding work that you see was commissioned by the master doctor Aloysius from France and his wife Tomasina, as a result of their devotion, and at their own expense, from Luca Signorelli of Cortona, a famous painter, who brought forth these forms in the year 1515

The patron ‘Aloysius’ was indeed a French doctor, Louis de Rodez, and one of the terms of the contract was that Signorelli and his family would receive free medical services whenever – and wherever – necessary. Apart from this, the artist was not paid. The altarpiece was painted for a chapel dedicated to St Christina of Bolsena in the church of St Francis in the Umbrian town of Montone. This explains why one of the saints depicted is the relatively obscure (as far as I am concerned) Christina… but we’ll come back to her. Let’s keep our feet on the ground for the time being.

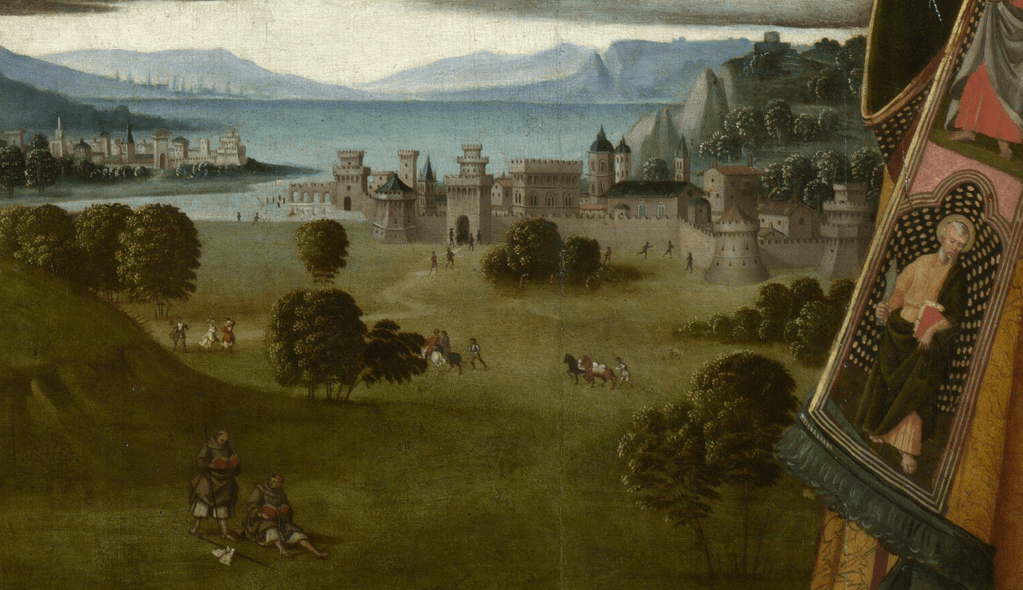

With two saints on the ground, standing to the left and right, it leaves Signorelli space for a fantastic landscape in the middle – and the details are truly delightful. To the right we see the edge of St Nicholas’s robes, and in particular one end of his embroidered stole. It is patterned with a series of niches occupied by standing saints. In the one we see here the knife in the man’s hand tells us that this is St Bartholomew. I’m guessing that all the others are apostles too, as St Peter, holding the keys of heaven, is at Nicholas’s left shoulder, partially hidden by the crozier. In the landscape we can see a broad meadow leading down to a lake. There is one walled town to the right, next to the lake, and two more on the left, each one smaller and fainter according to their distance. At the bottom of this detail are two Franciscans in their typical brown habits who appear to have taken a stroll, to appreciate the wonder of God’s creation, and to contemplate in relative solitude. Either that, or they are travelling from one preaching opportunity to another. They have both hitched up their skirts (Signorelli painted the altarpiece over two summer months – it would have been hot) and one has sat down. Both have large red books – the bible, or a prayer book, presumably. Their inclusion is undoubtedly related to the dedication of the church in which the altarpiece was located: St Francis. Maybe they are on their way to Montone. That is not the town represented, which is on a hilltop, but the lake might invoke Lake Trasimeno, which is not so far away. Well, it’s in the same part of the world (Umbria) but it is 33km away from Montone, over the hills…. It’s far more likely to be the Lago di Bolsena – Lake Bolsena – with the town on the waterfront representing Bolsena itself. This would partly explain why Signorelli has included this landscape. However, this naturalistic feature might also reflect Signorelli’s renewed interest in the paintings of Perugino and Pinturicchio which he would have seen in this area, and is also a result the renaissance interest in the world we live in and see all around us. It constitutes one of the ways of keeping us involved with the painting. If viewers can see and recognise the different elements of the landscape, it will draw them in, and help them to believe that the saints, too, are equally real. Above the head of the standing Franciscan are two women fighting, with a man who seems to be disclaiming any responsibility for their behaviour, and on the other side of the trees two groups make their way across the meadow on horseback. There is really no ‘significance’ to any of these details: they are entirely whimsical, but do keep us looking. The lake, however, is significant, and not only because Bolsena was the location of Christina’s major shrine.

The saint herself is one of the two standing on clouds on either side of the Virgin – who herself is standing on the heads of cherubim and seraphim peering down from similar clouds. Christina has long, blond hair falling down the back of her neck, but no headdress, which tells us she must be a virgin, and relatively young. She wears a green dress and a red cloak – which might be what originally confused me: she could have been a young, beardless St John the Evangelist, who often wears these colours, and can be shown with similar hair (and no headdress). However, she is holding an arrow in her right hand, and a millstone is tied around her neck, almost as if it is slung over her left shoulder like a broad-brimmed hat. The historical record of Christina’s life is remarkably blank, but devotion to her is rooted in the early church. Legend suggests she was born in the 3rd century in Tyre in modern-day Lebanon, although others suggest she was a native of Bolsena, where she is supposed to have died. Nearby, early Christian remains include the tomb of a woman with a name like Christina, and an associated shrine. She was clearly revered by the 6th century, when she is included in the procession of virgin saints in the mosaics at Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna. The legends that grew up around her suggest that, born into a pagan community, she was told about Christianity by an angel. To cut a long story short, this led to numerous tortures, until, according to the 2004 Catholic Martyrology, she was ‘thrown into the lake with a great weight of stone, but was saved by an angel’ – and this is the relevance of the lake. After enduring yet more tortures, ‘she completed the course of her martyrdom … being pierced with arrows’ – both the single arrow and the millstone are explained. If you are aware of The Mass at Bolsena – as depicted by Raphael – that too has a tangential connection, given that the miraculous event took place in the Basilica of Santa Christina in Bolsena, the location of her shrine.

The arrow which she holds, and the fact that she survived several attempts to kill her, makes her the perfect partner for St Sebastian. Although pierced with many arrows he was not killed at this attempt, but later succumbed to death by stoning. The light, falling from the left, glances across his torso, mapping the musculature of his svelte form. He stands with his legs straight and feet apart, not unlike Donatello’s St George (which Signorelli had probably seen when in Florence), or more relevantly, just like several of the figures in the artist’s fresco of The Resurrection of the Flesh in Orvieto Cathedral. It is not necessarily a coincidence that this building also contains the relic of the Miracle of Bolsena, as it could have informed Signorelli’s understanding of Christina’s story. The various stages of her martyrdom are, of course, recounted in The Golden Legend, and some were included in the predella of today’s altarpiece, which survives in the Louvre.

As so often, Mary is shown as personifying a number of distinct aspects of her character. The two angels each have one hand on a crown, which they hold above her head as the sign that she is Queen of Heaven. Each also holds a white lily in their other hand, reminding us of her purity and virginity. Meanwhile, as Theotokos – Mother of God – she holds the Christ Child effortlessly and, were we dealing with mere mortals, impossibly poised on her left hand.

Two last details: the child holds a sphere, patterned with blue and green forms. In the words of the spiritual, ‘He’s got the whole world in his hands’, even if we don’t recognise the individual land masses depicted. Christ is not just King of Heaven, but also Pantokrator – ‘Almighty’ or ‘ruler of all’. Mary, on the other hand, has what might appear to be a form of saddlebag. Two straps curl around her fingers, with a rectangular panel of brown fabric attached to each. This is a scapular, worn by specific groups of the devout as a sign of that very devotion. It’s not entirely unlike a tabard, with the two straps going over the shoulders, and the rectangles hanging over the back and chest. This is a brown scapular, which was particularly associated with the Carmelite Order, which does not seem to relate to the painting’s origins in a church dedicated to St Francis. It is not mentioned in the contract for the payment, nor in subsequent records which survive in the archives. But then – and I managed to get into the National Gallery’s library yesterday – it looks like it was added some time after the painting’s completion. When seen close to, the area around the scapular looks worn, as if it had been prepared for this additional detail to be painted on top of the original work. It has been done expertly: the way in which it loops around Mary’s hand looks entirely natural. However, without it we could see far more clearly how Mary’s left forefinger touches her son’s extended right foot with an extreme delicacy, which again gives a sense of his supernatural weightlessness. Although not original, it does remind us of the many roles played by the Virgin Mary. Of course, we’ll see more of these in Parmigianino’s Vision of Saint Jerome on Monday.