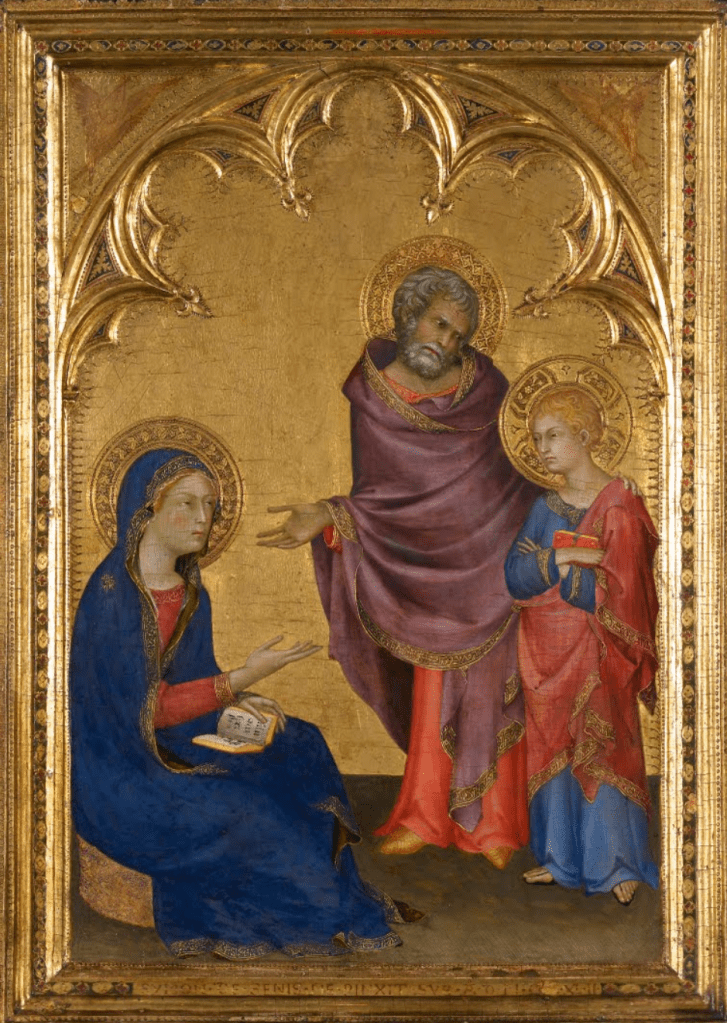

Simone Martini, Christ discovered in the Temple, 1342. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

As an undergraduate studying the History of Art, I and my fellow students held Simone Martini in especially high regard, finding our developing vocabulary inadequate to describe the ineffable beauty of his paintings. We were incredibly lucky to have a great, local treasure, the panels showing three saints and three angels in the Fitzwilliam, a public museum which belongs to the University of Cambridge. I will, of course, talk about these panels when I look at Simone‘s work this Monday, 3 March, the third in my series of lectures building up to the National Gallery’s Sienese exhibition, even though, sadly, they will not make the journey into London themselves. There will be no talks the following two weeks: I have regrettably had to reschedule the talk about the fourth artist, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, to 31 March – apologies to those who have been trying to book in the interim. So the fourth talk in the series will be the overview, Siena: The Rise of Painting, on Monday 24 March. To be honest, this won’t upset the flow of the series too much, as Ambrogio turns out to be the least well represented of the four main artists in the exhibition. His greatest work is undoubtedly a remarkable secular fresco cycle, the Allegory of Good and Bad Government in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. A thorough exploration of these paintings will be a fitting conclusion to the series, as the frescoes help to explain the ideology which made Siena such an important centre of the arts in the first half of the 14th century.

Having celebrated Simone Martini as a student, I have had little opportunity to talk about him since. Apart from anything else, none of his paintings have made their way to the National Gallery in London. However, I have now been in Merseyside for a year and have a new local treasure (which also happens to be one of the best): the so-called Christ discovered in the Temple at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. Having said that, it hasn’t been there for the past four months and won’t be for the next four either: it has recently returned from New York and will shortly be going on show in the exhibition in London.

I say ‘so-called’ because there are no signs of the titular Temple. What we do see is the Holy Family – Jesus, Mary and Joseph – engaged in a conversation which looks all too familiar, and familial, but not entirely happy. The painting was clearly a luxury object, the elaborate, engaged frame being both gilded and painted, with the flat gold background delicately tooled to enhance the framing and to create the resplendent haloes. Mary is seated on a gold cushion, while Joseph stands, his left arm on Jesus’s shoulder, apparently presenting him to his mother. The boy stands with his arms crossed, looking for all the world like a contemporary teenager – with the exception, of course, that he is wearing what the 14th century considered to be standard biblical clothing. I don’t doubt that the subject of the painting is related to the incident in which Jesus was discovered talking to the Elders in the Temple, but it would be worthwhile revisiting that episode so that we can see exactly how it fits in. The story can be found in the Gospel according to St Luke, Chapter 1, verses 41 – 52:

1 Now his parents went to Jerusalem every year at the feast of the passover. 42 And when he was twelve years old, they went up to Jerusalem after the custom of the feast. 43 And when they had fulfilled the days, as they returned, the child Jesus tarried behind in Jerusalem; and Joseph and his mother knew not of it. 44 But they, supposing him to have been in the company, went a day’s journey; and they sought him among their kinsfolk and acquaintance. 45 And when they found him not, they turned back again to Jerusalem, seeking him. 46 And it came to pass, that after three days they found him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the doctors, both hearing them, and asking them questions. 47 And all that heard him were astonished at his understanding and answers. 48 And when they saw him, they were amazed: and his mother said unto him, Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us? behold, thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing. 49 And he said unto them, How is it that ye sought me? wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business? 50 And they understood not the saying which he spake unto them. 51 And he went down with them, and came to Nazareth, and was subject unto them: but his mother kept all these sayings in her heart. 52 And Jesus increased in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man.

So – Jesus was 12, an age at which a child knows what’s what, although we still wouldn’t feel safe letting them travel to a nearby city on their own. Consequently, as far as I’m concerned, the idea of travelling for a day before realising that your son was not with you is (a) almost inexplicable and (b) surely terrifying. And then to go back and not find him for three days… I can’t imagine. This time-frame must be relevant, though – three days until he was seen again, as if he had died, and come back to life… It must look forward to the resurrection. Having finally found him, Mary attempts to get an explanation. “Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us? behold, thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing”. Is Jesus contrite, ashamed, or even apologetic? No! In one of those slightly insensitive statements which he very occasionally made, he replies, “How is it that ye sought me? wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business?”. I’m using the King James Version (published 1611) as I usually do, and find it interesting that when Mary says ‘father’ she says it with a small ‘f’, whereas when Jesus say ‘Father’, it is capitalised. It’s not something that Mary and Joseph could have heard, and I’ve always thought it would have been a real slap in the face for poor Joseph, the loyal stepfather, caring for Mary and bringing up somebody else’s Son. I’m also a little surprised that Mary and Joseph “understood not the saying which he spake unto them”, given that Mary had experienced the Annunciation, and Joseph had been blessed with an equivalent dream. However, it is notable that from this point on Jesus “was subject to them” – he clearly did as he was told – and “increased in wisdom and stature.” He grew up, in other words, both physically and mentally, and he presumably learnt how to deal with problems with more sensitivity and greater compassion.

Having reminded ourselves of the story, let’s have another look at the painting.

This is undoubtedly the right situation, but not the setting suggested by the title of the painting. We are not in the temple, as I said earlier, but then, there is no evidence where we are. Mary is seated on a very expensive looking gold cushion, on a nondescript floor. I suspect that, by removing the specifics of time and place, the story becomes more universal – and I wouldn’t mind betting that we have all experienced a similar situation, either with our own parents, or with our children. Let’s have a closer look to see how the details help us to read the narrative.

There’s not a lot to go on in this detail, admittedly, but it does help us to appreciate the material qualities of the painting as an object. The precisely carved, engaged frame includes a number of differently shaped and decorated elements. From the outside, going in, there are two flat sections, wider and narrower, with the inner one being carved in greater depth. Both are tooled with a repeating sequence of round forms. The next section has an undulating, wave-like profile, and contains another flat area tooled with ovals which enclose quatrefoils. These are alternately painted in blue and red. A projecting element frames this coloured border, and this curves down to the flat picture surface, after one final, thin strip. Inset within the top of the rectangular frame is a semi-circular moulding forming an arch, which is itself inset with five more semicircles containing further tri-lobed arches, with finials in the form of fleur-de-lis. Could this complex sequence of arches represent the Temple, I wonder? The spandrels to the top left and right of the main, round arch are painted with seraphim: six-winged angels’ heads. The thin, transparent paint allows them to glow, the light reflecting from the gold on which they are painted, their ethereal forms probably rendered more ethereal by some thinning of the paint over time – although there is little about this painting that suggests wear and tear. The seraphim, looking down from above, remind us that we are looking at a religious scene. They could also imply that, while absent from his earthly family, Jesus was nevertheless under the protection of the Heavenly Host – present, as he was, in his Father’s house. Joseph’s concern is all too clear. The tilt of his head to our right, and his eyes, looking in the same direction, speak of the attention he is paying his stepson, while the furrowed brow tells us he is worried. The grey hair, beard and eyebrows speak of his maturity.

Seen in relationship to Jesus – and a little closer in – Joseph’s expression might read another way. Concern, yes, but possibly a little disappointment too. Maybe even a little anger – it depends which eye you look at (emotions are so complex). Meanwhile, Jesus’s expression is very hard to read. From this detail alone we wouldn’t know what was going on, but having already seen the painting as a whole, we know that he is looking towards his mother.

Whatever Joseph’s expression says to you – and I think we all read expressions differently – there can be no doubt that the delicate placing of his hand on Jesus’s shoulder implies tender care, and the raised tip of the thumb, at the base of Jesus’s halo, implies that the boy has not been hauled into the presence of his mother by brute force, nor is he in any danger of running away. I could elaborate all the different elements of these two haloes, but I will leave you to look at them, differentiate between the forms from which they are constructed, and wonder at the number of different tools which must have been used by a highly-skilled goldsmith to make them. What I will point out is the cross in Jesus’s halo, which is just one of the things that tells us that this is indeed the Son of God. The gold on the hems is stuck on rather than tooled – it’s called mordant gilding. I love the way in which the patterning around the hem of Joseph’s cloak starts in front of his chest, curves down and then up to our right around his neck, emerging to curve up further before swooping down again across his chest, and leading to Jesus’s halo. This spiralling form seems to express the complexity of the relationship between stepfather and -son, and they way they are bound together. It also delicately frames the hem of Joseph’s red robe.

Isn’t body language eloquent? On its own Jesus’s expression wasn’t saying much, but with the crossed arms it speaks of mute refusal to communicate. Joseph’s subtle sway says so much, his head focussed on Jesus, the torso leaning towards Mary, led by the open offering of the hand – a gesture suggesting an opportunity to talk. Mary looks directly and clearly at her son, and gestures towards him just as clearly and directly, as if to take a welcome explanation. The hands are so important – Joseph’s and Mary’s outlined against the flat gold background, hanging unanswered in space, Jesus’s tucked away, ineloquent (and yet saying so much), Mary’s, resting on the open pages of her book, the thumb indicating the first word of the text…

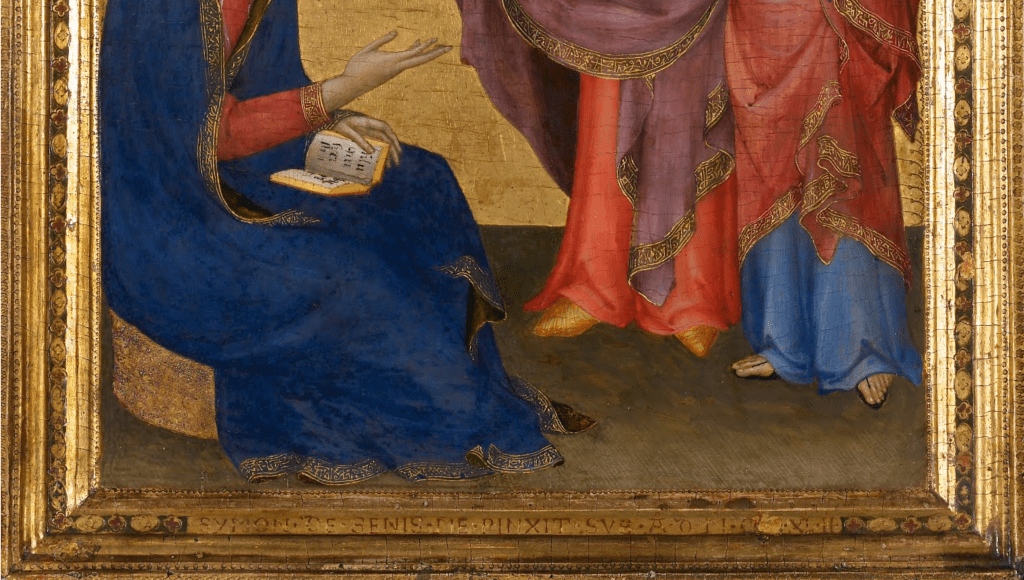

There is some distance between Mary and the men of the family – the gold, flat background seems to keep them apart. The men, on the other hand, are bound together not only by their physical proximity, and the way their forms overlap, but also by the echoing of their drapery. Jesus wears his traditional red cloak over a blue robe, while Joseph wears purple over vermillion. To my eye, the transition from vermillion to red, and purple to blue, results in a beautiful colour harmony. The lines, too, play their part: trace the patterns of the hems in your mind’s eye. The gold decoration falls along parallel, broken diagonals, and in both case the underside of the cloak, with no golden hem, hangs in a point at the bottom. The rise and fall of these fragments of golden embroidery remind me of a musical duet, with the melody rising and falling, shared between the two instruments – or the rhyming lines of a poem, perhaps. Maybe I am being overly imaginative, but Simone was friends with the poet Petrarch, who once described him as ‘our most delightful Simone’. He dedicated two of his verses to one of Simone’s portraits. I don’t think I’m going too far if I say that poetic beauty can be expressed in the fall of drapery or the echoing of hems. Simone also communicates through footwear, whether it is seen or unseen. Mary’s feet are completely hidden: she is a pure, respectable woman. Joseph, the most worldly of the three, wears ‘normal’ shoes, which are delicately hatched with the fine brushstrokes typical of egg tempera. Jesus, on the other hand, wears sandals. He would later tell his apostles to take no money with them on their travels, “Nor scrip for your journey, neither two coats, neither shoes, nor yet staves” (Matthew 10:10) – meaning no bag, no spare coat, no shoes and no walking stick. This text inspired the ‘unshod friars’ – members of a religious order who, following Christ’s exhortation, wore no shoes, or, at the most, only sandals. Even as a boy – who has, admittedly, just spent three days in his Father’s house – Jesus has already renounced contemporary footwear. At the bottom, running along the painted section of the frame, is the signature:

·SYMON·DE·SENIS·ME·PINXIT·SVE·A·D·M·CCC·XL·II·

“Simone of Siena painted me in the year of Our Lord 1342” – I can’t find any reference to the meaning of the letters ‘SVE’ though – if any of you are good at Latin (and in particular, medieval Latin inscriptions), what do you think?

What might seem to be most important for the understanding of this painting, though, is the book which Mary is holding, and what that text says.

Although worn, it is possible to read “fili quid fecisti nobis sic” which can be translated as, “Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us?” This is, of course, part of Luke 10:48, a quotation from the passage cited at the top of this essay. What we are witnessing is is undoubtedly the conversation arising from the discovery of Christ in the temple – but the biblical text only serves to confirm what we already knew. The sense of the painting, the ‘meaning’ of the narrative, is clear to the eye, given the eloquence of the imagery, the expressions, the body language… in many ways the image transcends the text. In one of his poems Petrarch said, ‘Simone must have been in Paradise…’ and at times, when he is not depicting a narrative, his heavenly style goes beyond words. No wonder our vocabularies failed us as students.

Fascinating Richard. I’m not sure about the SVE. Could it relate to the Servite order? Martini painted an altarpiece with Three Saints around 1320 for the Church of the Servites (Orvieto). The members of the order dedicated themselves to Mary.

Just a thought! 😁

LikeLike

Thanks – an interesting idea – but I don’t think it’s that. There is a really good suggestion for the patron of this painting (more of that on Monday), and it’s not the Servites.

LikeLike

Dear Richard,

As scholars have ascertained that Simone Martini painted the panel in Avignon I thought SVE could mean Siena Urbs / Vrbs Exeat

Anne-Marie

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a great idea – thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Richard, I registered for tonight’s lecture but it appears that 2 lots of £10 are being debited from my account. Also I’ve not received any link for the session but perhaps this is on its way! Thanks, Angela (Fenwick)

LikeLike

Hi Angela – I’ve just sent an email!

LikeLike