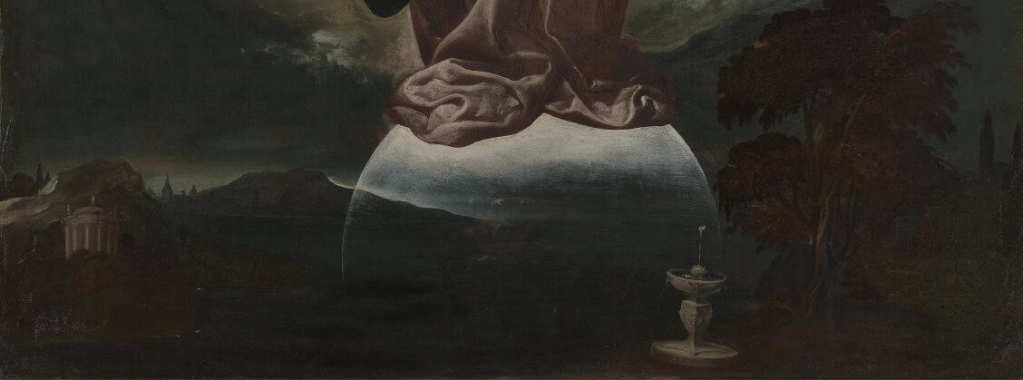

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson, 1893, Hampton University Museum, Hampton, VA.

I’m always glad to learn about new artists, and this week, for reasons which I hope are clear, I’ve decided to seek some out. Henry Ossawa Tanner promises to be the most exciting recent discovery. His style sits somewhere between Realism and Impressionism, the result of his training in the United States and his experiences in Paris, and it develops into something entirely original and personal.

Realism is nowhere near as famous as Impressionism, probably because the subject matter tends to be a little more intense and it never resorts to superficial effect. Although the term does have stylistic implications – it is undoubtedly naturalistic – ‘Realism’ refers more to the reality of the subject matter than to the appearance of the image. It was a term coined initially by Gustave Courbet in 1855 (as I mentioned in Picture Of The Day 10), and it relates to real-life events, and often subjects which are relevant to everyone, as opposed to the ‘History Paintings’ favoured by the Academies. These, are not necessarily ‘History’ but ‘Story’ paintings, narratives taken from the Bible or the lives of the saints, from classical history or myth. As it happens, Henry Ossawa Tanner was known for narrative paintings drawn from the bible – his father was a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal church – but also for his engagement with ‘Realism’, and especially in terms of the African American experience. It is true that, in previous centuries, art had dealt with what could be described as middle- or working-class subject matter in the genre of painting known, rather annoyingly, as Genre Painting. However, in focussing on normal people doing normal things for an inevitably elite audience, the artists often seemed to be looking down their noses and laughing.

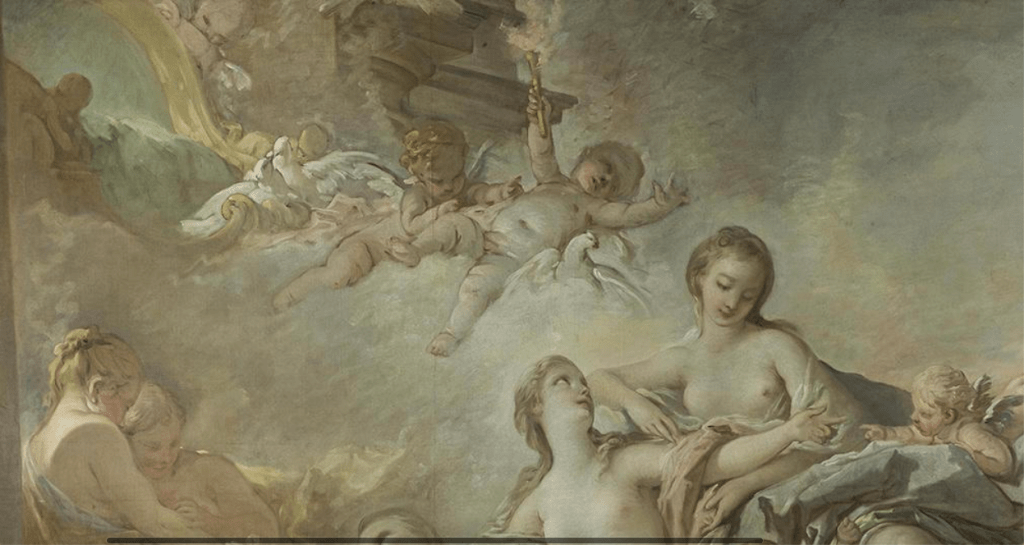

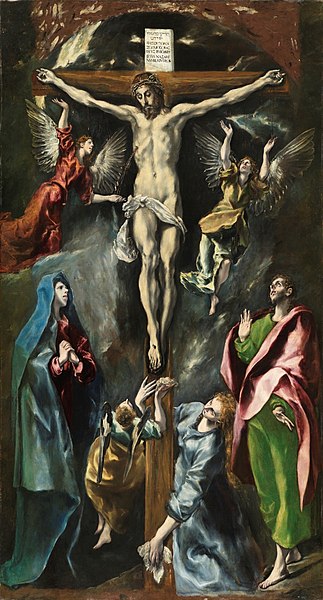

Not so with Realism – the lives of normal everyday people were dignified and given value. It was one of Tanner’s great skills: to look where no one else had, and to find value. In today’s picture we see an old man teaching a boy to play the banjo. Given the age difference we assume that they are grandfather and grandson, although there is nothing specifically to confirm this, apart from the fact that both seem so much at ease that they could easily be at home – a very humble home at that. There are pots and pans on the bare floorboards, and a jug, a plate, and some bread on the table in the background. There is a coat hook, a shelf and two chairs – the old man sits on one, a coat is thrown across the other. The room is not without decoration, though: two pictures are hung on the walls, too indistinct to identify.

There are two light sources, neither of which is visible. A fire on the right casts a warm glow on the floor, with some of the pots throwing the nearest floorboards into shadow. Foreground darkness is a traditional compositional tool, though: we tend to look from the dark towards the light, and so our eyes are led into the painting. The firelight also illuminated the back wall, with the table and jug casting shadows. This light is brighter than we might expect, but that is because illumination – or enlightenment – is one of Tanner’s themes. Light also comes from the left, as daylight enters a window or door, catching the faces of the two protagonists, giving them form, and character, and revealing their expressions.

This careful planning means that the couple are surrounded by light. It illuminates the floor around them and the wall behind, so they stand out, dark, but clear and distinct, even if the Realist attention to naturalistic detail is softened by an impressionistic blurring of form. The boy stands on the floor, legs close together and slightly bent, leaning against the old man’s leg, slightly unstable, slightly unsure. The grandfather is entirely stable, feet planted, secure. What we are witnessing is knowledge being passed from one generation to another.

The degree of focus, of concentration, is captivating. The banjo is clearly too large for the child to encompass its entire length or to bear its full weight. The old man holds the end of the neck, and keeps it raised at the right angle – but this is the full extent of his intervention. His other hand sits foursquare on his thigh. Both look intently at the boy’s plucking fingers, their joint focus, and the echoing positions of their left hands, expressing their shared experience. The fingers of the boy’s hand stretch to form a chord, while his right wrist is bent, the fingers arched to pluck. The light catches the back of his right hand in the same way that it catches his grandfather’s resting fist. It also falls on his forehead, eyelids, nose and lips. We can see that he knows he is learning: he is illuminated, enlightened. The light glancing across his grandfather’s face suggests something else: the exhaustion of a difficult life, perhaps, but with the consolation that the boy is starting to learn.

Henry Ossawa Tanner was not the first artist to depict black men playing the banjo, but you could argue that he was the first to give them real dignity. Historically it was as musicians – entertainers – that people of colour had been permitted a role (to what extent that has changed is debatable) but often in paintings this was reduced to stereotypes of mock minstrelsy. An exception might be the painting by Thomas Eakins, who was, tellingly, Tanner’s teacher.

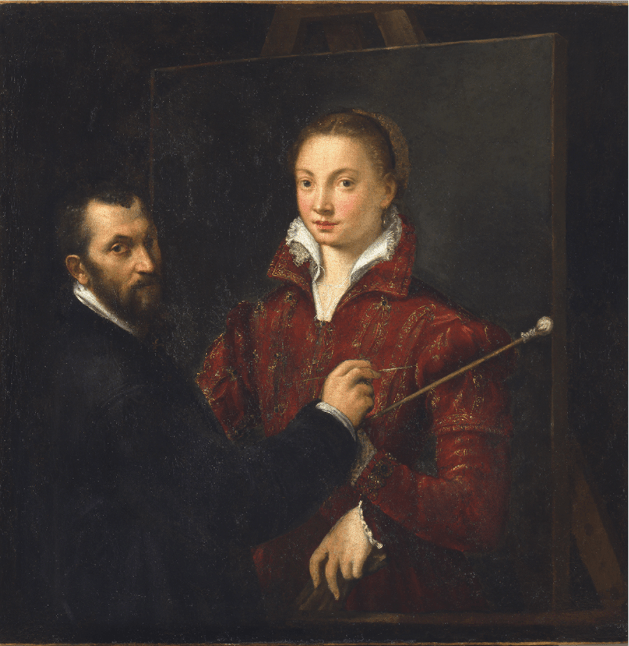

Thomas Eakins, Study for Negro Boy Dancing: The Banjo Player, NGA Washington.

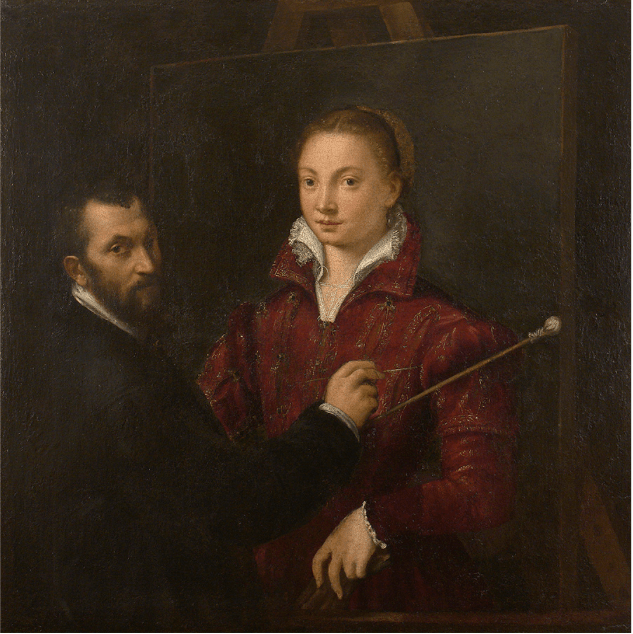

Thomas Eakins, Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, N.Y.

Tanner was born in Pittsburgh in 1859 to Benjamin – the minister – and Susan, who had been born into slavery in Virginia, but escaped to the north, and became a school teacher. Henry’s second name – Ossawa – was invented by his father, and refers to the town of Osawatomie, Kansas, where, in 1856, there had been a violent clash between abolitionists and pro-slavery partisans. Henry drew and painted from a young age, his artistic activity re-doubling while he was recovering from illness resulting from a difficult apprenticeship. Although his father had initially opposed his wish to become an artist, in 1880 he enrolled as the only black student of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Thomas Eakins’ teaching was an inspiration, and Eakins reciprocated, appreciating Tanner’s talent – not only was he a favourite student, but one of very few honoured by the master with a portrait, painted some two decades later (above right).

In 1891 Tanner visited Paris – and ended up settling there for the rest of his life. There were a few return visits to the States, during one of which he painted The Banjo Lesson. Back in France, though, he regularly had works accepted at the annual Salon, and his success there was just one of the reasons he chose to remain. That he was able to be successful was another. As he put it himself, ‘In America, I’m Henry Tanner, Negro artist, but in France, I’m “Monsieur Tanner, l’artiste américaine”’.

There’s so much more to say about this painting – about its debt to the European tradition, and to contemporary French art – but to be honest it has already been said so well by others that I am simply going to refer you elsewhere – a clear, thorough and easy-going essay, beautifully illustrated by Farisa Khalid on the Khan Academy website, and an even more thorough and entirely academic article, exploring the full significance of Tanner’s achievement, by Judith Wilson, from Contributions in Black Studies. I shall return to Tanner’s work in the coming weeks, though.