Johann Michael Fischer, Ottobeuren Abbey, 1737-1766, Bavaria, Germany.

Frescoes: J.J. and F.A. Zeiller; Stucco: J.M. Feichtmayr.

Today’s picture is a building! Or rather, the decoration of a building. I’ve named Fischer as the architect, although, to be honest, so many people were involved that it is hard to know who did what – but Fischer is generally credited with the overall concept of the building as it now stands. I’ve been to the abbey three times, once on my own, and twice leading groups – and it is visually one of the most exciting places I have ever been. Each time I have gasped, and I think the groups did too, although maybe not so audibly. Today’s post is a response to yesterday’s (Picture Of The Day 57) – and refers back to POTD 51, in that it is the best illustration I know that, contrary to popular opinion, the Rococo is not, of necessity, frivolous.

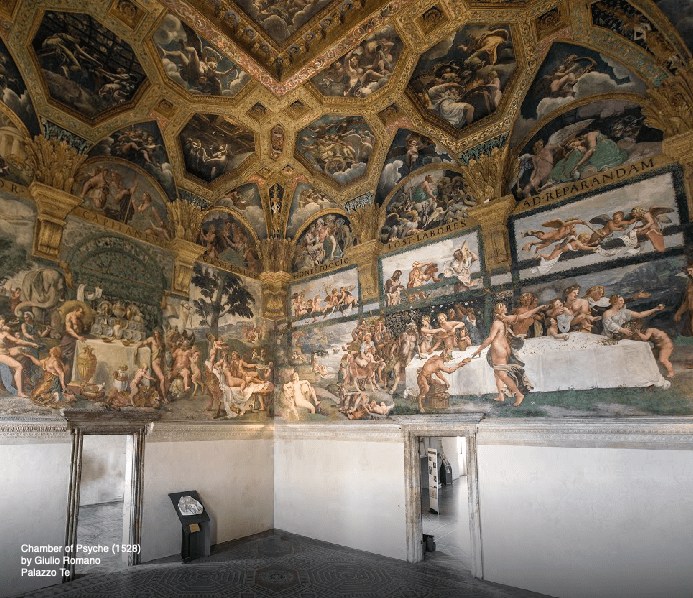

The Abbey has a long and complex history, but all I am going to say is that is was founded by the Blessed Toto in 764. Little is known of him, but he was certainly not the patron Saint of Oz. Or Kansas, for that matter. Long story short – it was secularised in 1802, and re-founded in 1834. The irony about the secularisation was that, after over 1000 years of history, it had only reached its present, glorious form some 46 years before. At first glance it is – incomprehensible. Every surface is decorated – I swear, every square centimetre – but everything has a purpose and a reason. In most books the style is described as ‘Bavarian Baroque’, but that can only be justified by the alliteration, or if you deny the existence of the Rococo – because it is definitely Rococo. The architectural forms are dissolved in the complexity of the decorative details, the walls dematerialise, and nothing is solid. The predominant colour is white, and the windows – although not visible in this photo, which is part of the genius of the architecture – are large, allowing vast quantities of light to flood the building. It is, simply, heavenly. And that is its very purpose – the dematerialisation, the lack of solidity, the other-worldliness of it all, is the very opposite of the material world in which we live and work – this is a world of light, of spirit and of joy. If Heaven is like this I want to go!

There are quite a few side altars, all dedicated to local saints and Benedictine heroes (it is, and always has been, a Benedictine establishment), but I will just focus on the central themes. In the image above, you have to imagine that we have just entered through the West Door, through the narthex and under the organ loft. We are looking towards the high altar, seen impossibly far away in the distance. There is one dome above the choir, and a second, closer to us, above the crossing – the large arches opening to the north and south transepts (left and right) are just visible – and that is where we shall start. Imagine walking along the nave until you reach the crossing, and then looking up. This is what you would see.

In the midst of the thin blue luminous sky, the zenith is even more brilliant. At its centre we see a dove – the Holy Spirit is descending, surrounded by a circle of angels. There are seven of them, so they must be all the archangels as mentioned by Raphael (POTD 4). Light flows down past the broken pediment of a monumental arch, which is flanked on either side by two obelisks – which, in their turn, return our gaze to the Holy Spirit. Framed by the arch – a succession of arches, even – is a woman standing in prayer, wearing a red robe and a blue cloak: the Virgin Mary. She is surrounded by a group of men, looking up to the sky, hands raised or clasped in prayer, each with a small flame above their head. We are witnessing Pentecost – the descent of the Holy Spirit, when, fifty days after the Resurrection of Christ, the Apostles were gathered in an upper room, and everyone outside could suddenly understand them as if they were speaking in their own native tongues. This was the point at which the Apostles were truly empowered to go and evangelise, to teach the Word of God. All around the base of the dome we see different trees, different animals – and, above all, different people. The whole world is represented here.

If we head back half way towards the West Door, turn around and look back up at the dome, Mary is just as clearly visible. The dome is supported by four massive arches. The one on the far side leads to the choir, those on left and right to the North and South Transepts respectively, and the one closest to us, to the Nave, where we are standing. The base of the dome rests on the top of these arches, and in between four triangular forms hang down – we can only see two of them here. They are known as pendentives – because they hang down. Each has an elaborate stucco frame, almost like an inverted pear, containing a fresco. As there are four of them, you can often guess who would be painted there, and in this case you would probably be right – the Four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. In the pendentive on the left you may be able to see a seated man wearing red and green – the traditional colours of John the Evangelist – and on the right, there is an angel reaching down towards a man in blue. The angel is symbolic of St Matthew. The Holy Spirit has inspired the Apostles to evangelise in the dome, and their message is put into words by these four Evangelists. The arches supporting the dome spring from an entablature, which is continuous around the whole building. At the crossing it is supported by faux-marble pilasters and columns. Underneath each of the pendentives, sitting on top of the entablature, there is a figure modelled out of white stucco. They are too small to identify here, but the one on the left wears a papal triple tiara, while the one on the right has a Bishop’s mitre. They are two of the four Doctors of the Church – Sts Gregory, Ambrose, Augustine and Jerome. The other two are on the side nearer to us, underneath Sts Mark and Luke, who are in the pendentives that we cannot see. Their writings, an interpretation of the gospels, have a special authority within the church, and are fundamental to its teachings.

If we bring our eyes down from heaven, we will see the font on our left, and the pulpit on out right. I’ve always liked Baroque and Rococo pulpits, because I know that, should I ever be stuck there in the midst of an especially long and dreary sermon, there would be plenty to look at. Some of the best are in Belgium, as it happens – maybe the preachers there are more than usually dull. Nevertheless, this is where the Priest will interpret the Gospels, and the teachings of the Doctors, to the uneducated masses like myself (I couldn’t possibly speak for you). He would inevitably be inspired by the Holy Spirit to do this, which is why the dove appears more often than not on the underside of the sounding board. Both this and the font are remarkable structures, but I am especially fond of the font. In the photograph above, on the left, you can just see the lid of the font itself at the very bottom of the image. It is then topped by the most remarkable superstructure. Standing on what appears to be a platform you can see the Baptism of Christ, with John the Baptist standing on the left, pouring water over the kneeling figure of Jesus. Beams of golden light descend from the Holy Spirit, which is as far above Jesus as he is above the font, and just above him, God the Father peers down from a cloud. As it happens, that is not a platform on which the Baptism is taking place, but a sort of frame. And if you were a baby being baptised, held in the arms of a priest, and looked up, this is what you would see.

It is a remarkably good thing that babies are myopic, because I think this would be absolutely terrifying. The angel at the bottom right is gesturing towards a gilded serpent, with an apple in its mouth. There you are, a tiny baby, about to have water poured over your head, and already temptation is in view. And just over the brow of a marble frame, there is a gilded relief with a tree. You can’t see it from here, but that relief shows the Fall – Adam and Eve are in the process of accepting another version of that self-same apple. And then beyond… let’s get in a little closer…

Yes, the Baptism in full view, and above that, the Holy Spirit, and even higher, God the Father. The Holy Trinity, looking down over you, which, if only you could focus, might calm your nerves – although the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is still the closest thing to you…

So – overall – we enter the church, and above the crossing we see the Dome in which the Holy Spirit inspires the Apostles with the gift of tongues so that they can go out and preach the word of God. Below them, the Four Evangelists write down the Good News of the Gospels, interpreted by the Four Doctors, who complete the teaching of the church. Once we have undergone the Sacrament of Baptism, we become full members of this church, and the Sermons we hear from the pulpit explain all of this – from the Holy Spirit, through the Apostles to the Doctors – so that we know what to believe, and understand our duties and our responsibilities, and we can head back out into the world to lead good lives. It covers just about everything, really. And ‘everything’ could hardly be called frivolous.