Pinturicchio, The Baglione Chapel, 1501, Santa Maria Maggiore, Spello.

Another request today, and this time, for an entire chapel! It’s in the charming Umbrian hill town of Spello, and well worth the visit – something to look forward to when we can get out again, and travel. One of the things I love about Umbria is the fact that there isn’t a huge amount of art. This may sound counterintuitive, but this does mean that you can look at things properly, give them the right amount of attention, and still have plenty of time to wander through the picturesque streets and enjoy a relaxed and delicious lunch. By the time I’ve got into the Uffizi in Florence – and even before I’ve seen any of the paintings – I am already in need a holiday. It’s all a lot more relaxed if you go to some of these less visited towns.

We know very little about the artist, or about this particular commission, to be honest. We’re not even sure when he was born – although the traditional date, based on dodgy information, is 1454. Nor do we know with whom he trained. The only things we do know about his early life is that he was born in Perugia, the son of Betto di Biagio, and was christened Bernardino. His first important work was in Rome, and after painting the apartments of the notorious Borgia Pope Alexander VI, he was summoned to Spello in 1500.

The chapel he was commissioned to paint is an addition to the church of Santa Maria Maggiore. For years it served as the Sacrament Chapel: the consecrated host, which Roman Catholics believe is the actual body of Christ, was reserved in a tabernacle so that you could pray there in the physical presence of God. But the function of the chapel changed in 1874, as it did again 100 years later when a restoration removed any traces of Ecclesiastical furniture. Now it is hard to see how the chapel would have functioned. Of course, this does mean that you can see the frescoes better, as well as the delicate, 16th-Century ceramic pavement from Deruta.

The chapel is almost square, and entered from about two thirds of the way along the nave of the church, which is decorated in a rather overblown baroque style. Don’t get me wrong – I love the Baroque – but it’s not always good. Entering through a round-topped arch, you are confronted with three more almost identical arches opening up into three alternative universes – although it is worth remembering that the entrance arch is the only one that is solid. All of the ‘architecture’ that you can see in these photographs was painted by Pinturicchio and his studio. The ceiling is decorated with four Sibyls – the female equivalents of prophets – but as they are by a different artist, and in a rather poor condition – I shall let them go for the time being.

Directly in front of you is the Nativity. It is framed in the same way as the frescoes on the walls to left and right: two square pillars support an arch decorated with inlaid marbles, and a low wall prevents us from climbing in to the verdant landscape. But remember, there are no pillars, no arch and no wall – all of this is painting – fictive, or imaginary, architecture. Central, and just below our eye-level, the Christ Child lies on the ground – a true sign of his humility. His mother Mary kneels to our right, with Joseph standing still further off, the Ox and Ass looking on from behind. The stable has been scrappily thrown together from the ruins of a Roman building, including two square pillars not unlike the two framing the fresco. This is a common symbol that the rise of Christianity will coincide with the fall of Rome. A choir of angels stands secure on a cloud, slightly closer to us than the stable roof, and the shepherds approach from the left. Meanwhile the Magi wait their turn in the middle ground.

If we now turn our attention to the wall on the left as we enter, we see the Annunciation (compare it with Piero’s version, POTD 7). It is framed in the same way as the Nativity, but rather than a green meadow, we seem to have a stage that stretches away at the same level as the top of the low wall. The fictive entrance acts as the proscenium arch in a theatre, with entrances left and right. The continuity of the space is evoked by the door on the back of the left wall, which is cut off by the pillar supporting the proscenium arch, and by the equivalent wall continuing off to the right. Mary would have been on stage as the curtains opened, standing at her lectern reading of the prophecies of the Messiah’s birth. The angel has entered Stage Right – the audience’s left – and… I think I’ve just had a revelation! Almost all Italian Annunciations have the Angel Gabriel on the left, and the Virgin Mary on the right. About 5% show them the other way round, and no one has ever been able to explain to me why that should be. The assumption has always been that, as we read from left to right, that is the way that the story should progress. However, in Northern European art, the image is more often the other way round. I can’t give you the figures, but maybe as many as 25%. So – why does Gabriel enter from the left? I’ve just realised that it must go back to the societal ‘leftism’ I mentioned on Saturday (POTD 38). Christ raises the blessed with his right hand, and condemns the damned with his left. As a result of this, in medieval mystery plays the angels would always appear Stage Right, and the devils, Stage Left – a tradition which continues with the goodies and baddies in a traditional pantomime. So of course it makes sense for Gabriel to enter from Stage Right, and therefore appear on our left. And I’ve been worrying about that for 30 years! Maybe the Germans didn’t have so much religious drama. Meanwhile, God the Father flies in from above, a true Deus ex Machina, and the Holy Spirit descends. He is currently just above the Virgin’s right arm, heading towards her ear. I’ll explain why another day. On the wall to our right a portrait is hanging.

This is a self portrait. It shows a painting of the artist as part of the decoration of the Virgin’s house, his name written on the plaque underneath in Latin, ‘Bernardinus Pictoricius Perusinus’ – Bernardino Pinturicchio from Perugia. He came from Perugia, but couldn’t use ‘Perugino’ as his nickname, because that was already taken. Indeed, Perugino had already painted a self portrait like this, with a very similar inscription. It’s in Perugia, his hometown, in the frescoes he painted for the Money Changers Guild between 1497 & 1500. This was just before Pinturicchio did the same thing – the date of the completion of the Baglione Chapel is at the top of the pilaster on the left of this detail: MCCCCCI, or 1501. The name he signs himself with, Pictoricius – Pinturricchio – tells us something else about him. He was very short. It means ‘little painter’.

The perspective of the Annunciation suggests that we have not fully entered the chapel – we are not in the middle of the square – as the arches do not recede symmetrically. There also appear to be a slight shift in the perspective as you get beyond the marble floor, and into the enclosed garden – maybe this is all meant to be a painted backdrop? The situation is different on the opposite wall, which shows Christ Among the Doctors.

It is now twelve years since the Nativity (according to Luke 2:42), and Jesus is centre stage, standing on a marble pavement discussing theology with an array of adults. They have given him space, and many have discarded their books on the floor, because their knowledge and experience is no match for this boy. Worse than not being able to keep up with your child’s home schooling, Mary and Joseph had headed home after their yearly visit to Jerusalem, only to realise that they had left Jesus behind. I hope you have never lost your children but it must be terrifying.

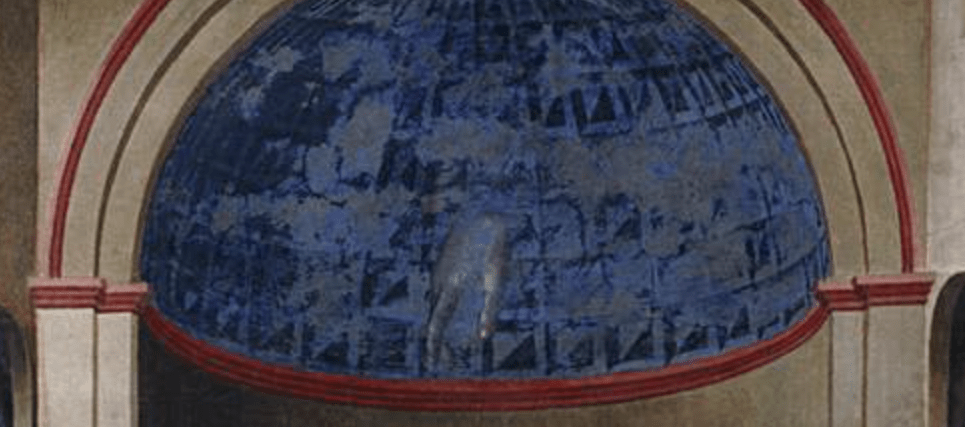

Finally they have found him, and appear, with haloes, and gesturing towards him, at the front on the right. They are wearing their traditionally coloured clothes – yellow for Joseph and blue for Mary. He stands on the central axis of the painting, with the orthogonals – the parallel lines going away from you into the painting – converging on either side of him. However, he is not at the vanishing point. That is located in the dark entrance to the temple – the perspective is encouraging us to go to church. Pinturicchio has created the renaissance architect’s dream – a symmetrical, centrally planned church. Octagonal in ground plan, it has a porch on four sides (I’m taking the one at the back for granted). It is orderly and symmetrical, and therefore approaches perfection: symmetry is, simply, divine. The dome is also octagonal, and not entirely unlike the dome of Florence Cathedral – although, unlike most of his contemporaries, including those from Umbria, it seems likely that Pinturicchio never visited the Tuscan city.

The temple sits in the middle of a field, not entirely unlike San Biagio, just outside the walls of Montepulciano – although the fresco can’t have been inspired by that example, as the church we see today, with its cruciform ground plan, would not be started until 1518. The idea actually comes from the Sistine Chapel, and Perugino’s fresco of Christ Giving the Keys to St Peter, in which the action of the painting takes place in the foreground, with a vast, perspectival pavement leading back to an octagonal temple with porticoes on four sides. One of Pinturicchio’s first jobs might well have been assisting Perugino in the creation of this fresco in 1481-82. Twenty years later, he still remembered the experience – and the composition – and adapted it for his own use.

A large number of the learned have gathered around Jesus, but more of them crowd in on the left of the painting. This leaves more space for us to see Joseph and Mary clearly on the right.

At the front on the far left – behind the two children who are clearly part of the Temple’s early learning programme – is a man entirely dressed in black. Compared to all the other faces here, his is far more specific: a long chin, sagging jowls, swept back, greying hair and a protruding nose above a pinched mouth. Compare it with the idealisation of the face on the right in this detail – the large, oval eyes, the simplified forms of the nose, mouth and chin. Clutching a book, on the right we have scholarship’s young dream. The man in black is the reality. He is the patron of the chapel, after whom it is named: Troilo Baglione. He was Prior of Santa Maria Maggiore from 1499-1501, after which he left Spello having been appointed Bishop of Perugia. He died five years later. Sadly we don’t know how he knew Pinturicchio, nor what he wanted from this decoration, but it is wonderfully coherent. Despite their poor condition, the Sibyls on the ceiling are there to prophesy the coming of the Messiah, whose immanence is then announced on the left-hand wall. But this is only an introduction – the perspective tells us that we have not yet fully entered the chapel, we are not yet at the centre of the story. Christ’s presence is made manifest as we move around in a clockwise direction. Starting with the left wall, we move to the one opposite the entrance, where Christ, as a baby, is lying on the ground, entirely central to the story and in the painting. Shifting once again to the wall on the right, he is still central, but now standing on his own two feet, already breaking free of parental constraints at an unnervingly young age. With the perspective centred, we too have arrived, fully, into the chapel, into an understanding of Christ, and we are witnesses to his understanding of the world. As the Sacrament Chapel, this would have made perfect sense – Christ is announced, is born, and is present in the Temple, both as a painted image and in the consecrated host. As a work of art it is a perfect three-act play – with prologue. And, if we have visited in the morning, it should set us up nicely for a wonderful Umbrian lunch.