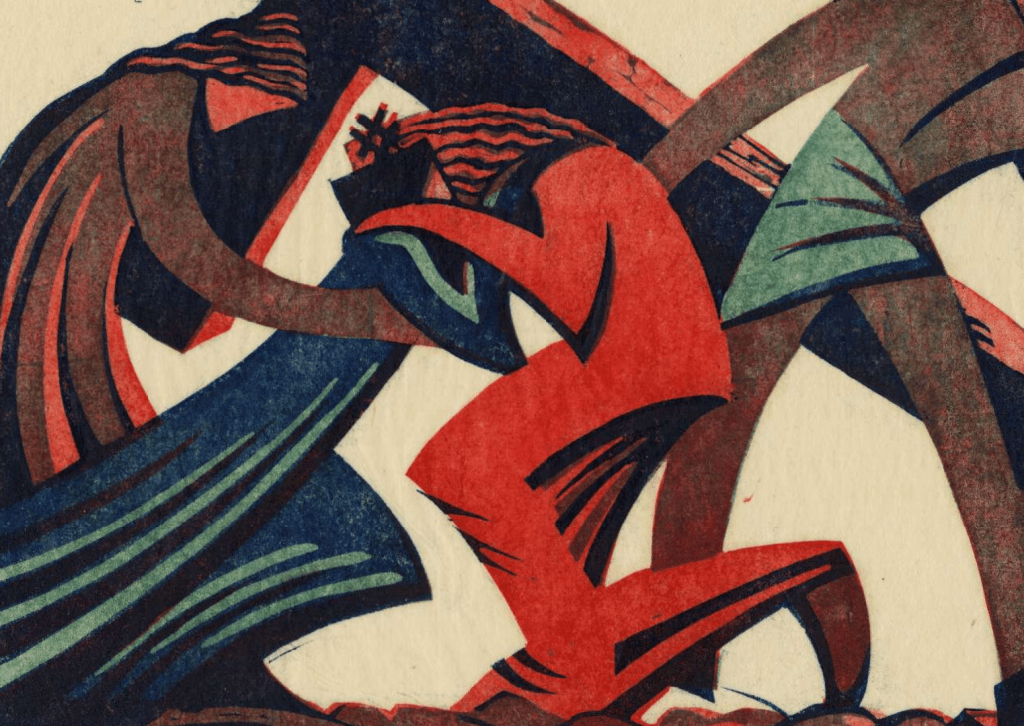

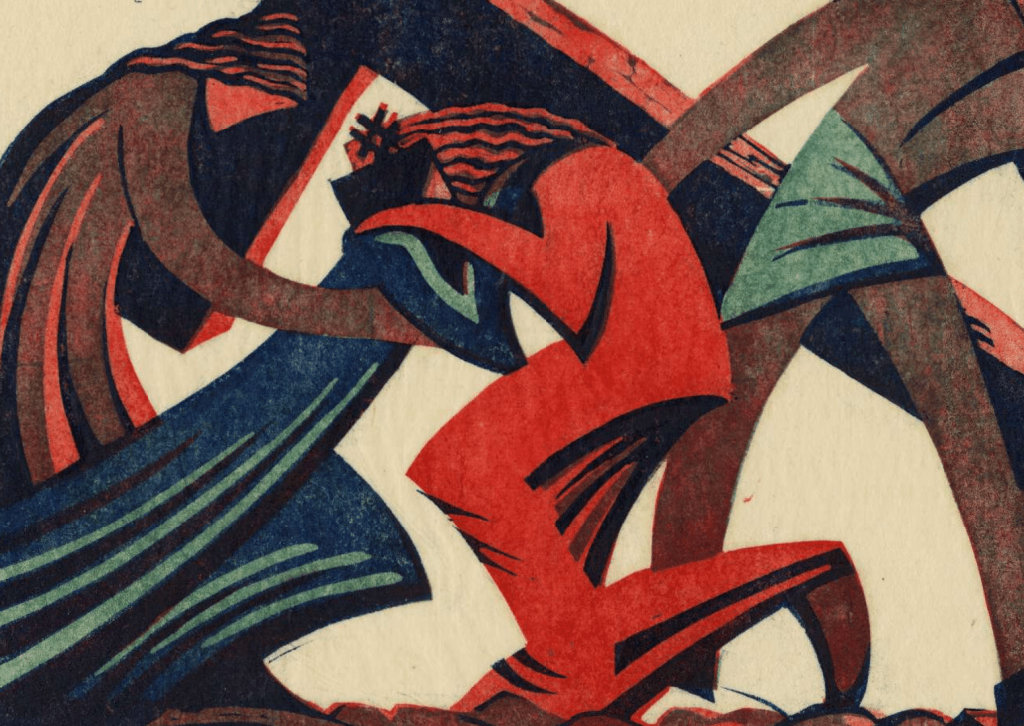

Sybil Andrews, Via Dolorosa, 1935. British Museum, London.

I started this blog, as I’m sure most of you know, just before we went into lockdown. One of the results of that remarkable year (or two) was that we realised that being negative could be a positive – i.e. testing negative for covid was a good thing. Two years later, in July 2022, I was getting particularly interested in the concept of negative space – and I wanted to re-post a blog I wrote then as it features the work of Sybil Andrews, who is also included in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition The Printmaker’s Art. I will show you the work in question in the second of my talks, …to Rego, this Monday, 15 January at 6pm, which covers the rich array of 20th and 21st century prints in the exhibition. If you weren’t able to make Part 1, don’t worry! Monday’s talk will cover different material, and introduce new ideas, so will effectively be ‘free-standing’ – and I’ll add in any ‘repeat’ information as necessary (it’ll be good revision for me!). After this, the next two talks will be on January 29 and February 5, and will introduce two exhibitions at the National Gallery, about Pesellino and Liotard respectively. In between these I have arranged another set of in-person tours of the National Gallery. If you haven’t managed to get to one of these so far, it might be as well to start at the very beginning, with NG01 – The Early Italians, on Thursday 1 February at 11:00am. This will look at work from the 13th and 14th Centuries. However, if you want to jump forward to the 15th Century, then NG02 – The Early Renaissance (in Florence), will take place twice on Wednesday 31 January at 11am and the Wednesday 31 January at 2.30pm. The day before I will also deliver NG03 – The Northern Renaissance, starting (I hope!) with The Arnolfini Portrait. Again there will be two talks, on Tuesday 30 January at 11am and Tuesday 30 January at 2.30pm. I know the dates seem odd, with the chronology going in opposite directions, but I have my reasons. As ever, all this (and sometimes more) will soon be in the diary. Click on the blue links to book via Eventbrite, and please check that you are clicking on the right link. And if you have booked already, please check you have tickets for the right time, as I might have sent out the wrong links (for which, if I did, many apologies). While I’m at it, if anyone missed my talk on The Impressionists on Paper at the Royal Academy, I will be repeating it on Tuesday 23 January at 6pm for ARTScapades – and if you’re not free then, they record their talks, so you can always catch up later. But I should return to The Printmaker’s Art, and the wonderful Sybil Andrews who I enjoyed getting to know back in 2022 – and especially the Via Dolorosa, which became a particular favourite.

The subject is not strictly biblical, but rather, part of church tradition. The Via Dolorosa is the Way of Sorrow, and is a processional, pilgrimage route in Jerusalem, taken by the faithful who want to follow the steps that Jesus took on the way to his crucifixion. The current route was established in the 18th Century, but is based on earlier, medieval versions. Although this print was executed in 1935, a version of it was later incorporated in a series of Stations of the Cross which Sybil Andrews worked on from 1946-78, in which it represents Station IV: Christ meets his Mother. The series was never completed – Andrews made only 10 of the 14 traditional Stations – and although Station V marks the point at which Simon of Cyrene takes the cross, he is already present. Simon’s role on the road to Calvary is mentioned in all three synoptic gospels. For example, in Matthew 27: 31-32 we read,

31 And after that they had mocked him [Jesus], they took the robe off from him, and put his own raiment on him, and led him away to crucify him.

32 And as they came out, they found a man of Cyrene, Simon by name: him they compelled to bear his cross.

In the linocut Jesus is wearing red, ‘his own raiment’, as opposed to the ‘royal’ purple garment in which he was dressed as part of the process of being mocked by some of the bystanders. Simon, already bearing the cross, which ways down between the broad arcs of both arms, seems to wear nothing but a loin cloth. In her grief, the Virgin, in her traditional blue, lunges at her son in desperation, her left knee bent, her right leg stretching behind. The long, urgent reach of her body makes a strong diagonal from the bottom left corner of the image up towards Jesus’s head. He collapses around her, his face lost behind hers, her face hidden by his left arm, which crosses over her right. Their hands rest on each other’s shoulders, the echoing gestures complemented by the sharp inflections of their elbows: these two people are in harmony, they share a common grief. To the left of the Virgin is Mary Magdalene – identified by her long, red, flowing robe (darker than Jesus’s to ensure that he is the focus of attention), and by her long, red, flowing hair – which echoes that of Jesus.

The Virgin stretches up between the Magdalene and Jesus, as if they are a pair of brackets containing her. The Magdalene’s form curves in from the left, and Jesus’s from the right, showing how they try to comfort Mary in her inconsolable grief, but also how they support her. One of the Magdalene’s arms stretches under the Virgin’s, while Jesus’s rests on it, setting up a rhythm linking all three figures. And yet Mary is left isolated, the blue ringing out clearly against the off-white background of the paper. The space between the Virgin and Jesus reminds me of nothing so much as a bolt of lightning, as if that is what has struck her down. It is this ‘negative space’ which fascinates me. Put succinctly (I hope), the ‘positive space’ is the space taken up by the subject matter – in this case Mary and Jesus. The ‘negative space’ is the space in between – all of the composition which is theoretically not part of the subject. It is something that intrigued Sybil Andrews, and I was, in turn, intrigued to read in a biography (details below), that she found reliefs from the Chinese Han dynasty at the Victoria and Albert Museum ‘“tremendously exciting,”… especially the artists’ use of negative space’. I’d show you an example, but, to be honest, I can’t quite pin down what (in the V&A) is being referred to here, and anyway, it might get in the way…

However, look at the negative space created by Simon of Cyrene’s legs, and the equivalent shape formed by Jesus’s leg and foot: both have a similar, straight diagonal at the top (leading in different directions), and a similar broad curve leading down from the upper end of this diagonal. These similar, off-white forms are part of the rhythm of the image. Notice also the curving, triangular section between Jesus’s legs and Simon’s. The same shape appears under Simon’s left arm: another echo, more harmony.

At the top of the image Andrews has titled and signed the work, labelling it as the ‘1st State, No. 1’ – she made other ‘1st states’, apparently, with only minor variations to the wood grain of the cross, before printing the edition. The looming diagonals of the cross help to structure the composition, and reinforce the energy of the Virgin’s dramatic move towards her son. Indeed, the two diagonals of the cross are an abstraction of the bodies of Mary and Jesus. The cross also frames the figures, with the negative space between it and the embracing figures of Jesus and his Mother pushing them towards us.

This is a linocut, or linoleum block print, a technique invented early in the 20th Century, of which Sybil Andrews was one of the first exponents. I will talk more about the technique, and Andrews’ use of it, on Monday. For now, I will limit myself to pointing out that this image uses only three colours of ink, described by the British Museum (which owns this particular version) as ‘red, viridian, dark blue’. The red defines Jesus’s robe, the Magdalene’s face and the sides of the cross, the viridian, like a jade green, can be seen in Simon’s loin cloth and the highlights of the Virgin’s drapery, while the dark blue forms the rest of this robe. Everything else you see is a combination of two of these colours, or, in the case of what might look like black, all three. Three different ‘blocks’ were used, each cut into a single sheet of linoleum, with each being inked in succession. The paper was carefully lined up, laid on top of the blocks, and pressed down. Inevitably the ink would ‘bleed’ out from the blocks, so the printed paper, as a whole, looks like this:

When framing a print, the frame is often an equivalent to the size of the paper as a whole, while the mount is cut to reveal only the image – basically, the cropped version that I showed you first. But if this is a 20th Century technique, what could be the relevance to Mary Beale, an artist working in the 17th Century? Well, compare these two details:

A version of the linocut, and the painting from which this detail comes, both belong to the Moyses Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds, and both are on show there now [or were, back in 2022…]. The museum is currently exhibiting their collection of Andrews’ linocuts in a display which will be on show until September at the latest – although I couldn’t find any secure information about the dates (I did ask, but to no avail…). Having spent some time looking at Via Dolorosa, I was then struck by this detail from one of Beale’s portraits. The deep blue in the depiction of the Virgin Mary is derived from the traditional medieval iconography, and relates, in part, to the expense of the pigment ultramarine, the very pigment which Beale is using here. Colouristically, therefore, there is a connection between the two images. In addition, though, the highlights and dark shadows in this oil painting create a counterpoint with the Virgin’s robe in the linocut, I think. Beale makes a very specific choice to splay the fingers of this hand, creating curving triangular forms, not unlike those seen in the print, which exist as blue ‘negative spaces’ between the fingers, and between the forefinger and the hem of the bodice. I was also impressed by the way in which the chemise forms a long, gentle curve which approximates to the more linear, geometric form created by the horizontal of the top of the hand and the diagonals of the blue bodice leading up to the shoulders, a rhythmic form which I imagine Sybil Andrews would have enjoyed. The detail comes from this painting:

Traditionally described as a self portrait, I was happy to read that Penelope Hunting, author of the most recent and authoritative book on the subject, My Dearest Heart: The Artist Mary Beale, doubts this identification. I’m slightly baffled as to what the subject of this painting is, though: if you have any thoughts about the urn and brazier, I’d be interested to hear them (I have some ideas, as it happens, and they make more sense if this isn’t Beale!) While I’m talking bibliography, there is also a recent example dedicated to Sybil Andrews, On the Curve, by Janet Nicol, although it has precious little about her art. Jenny Uglow’s Sybil and Cyril: Cutting through Time is certainly more incisive (pun intended).

Having been struck by the ties between what are otherwise two unconnected images – and let’s face it, if I had seen the works in two separate museums I would never have made the connection – I was also struck by the notion of ‘negative space’ – something which is not, supposedly, the subject of a composition, but is a vital part of it. Had you heard of either artist before? You’re a sophisticated lot, so I’m sure you had. But they do not exist in a standard ‘History of Art’. Indeed, until relatively recently, women had been notably absent – certainly before the 20th Century. And yet, they were vital, even important in their own day. But since their deaths they have become negative spaces – notable for their absence – and I can’t help thinking that the concept is a valuable tool for thinking about a history of the art made by women. Which is precisely why I talked about the two artists together back in July 2022.

Thanks Richard for a very interesting subject. Your last paragraph was thought-provoking. I love the idea of women’s art being a negative space- a space without which male, positive art would not exist.

LikeLike

Good morning The links below do not seem to work and on Eventbrite it comes up with the day before- Northern Renaissance I would like to book two tickets for the above tour. Thank you Elizabeth Eyre

Sent from Mailhttps://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?LinkId=550986 for Windows

LikeLike

Thank you Elizabeth, and for anyone else concerned, the correct links should now be posted in all the right places!

LikeLike