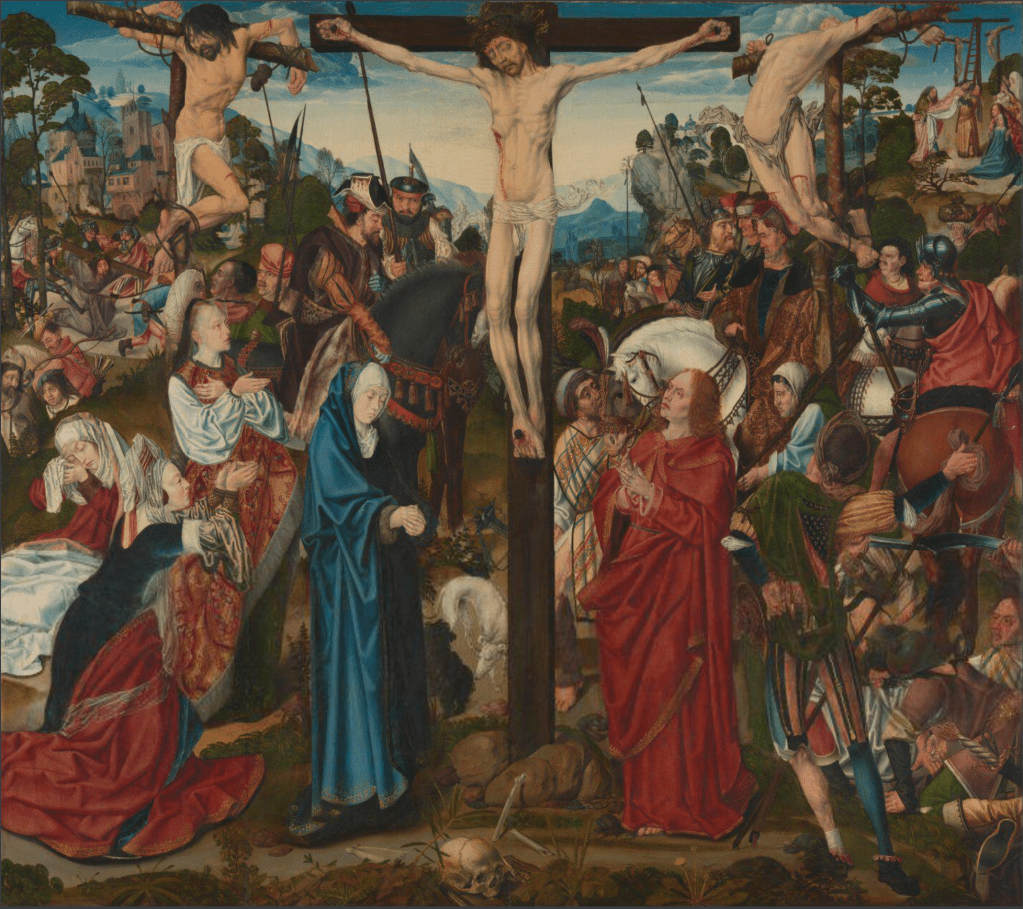

The Master of the Aachen Altarpiece, The Crucifixion, about 1490-5. The National Gallery, London.

I’m really enjoying getting to know the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool – it has a fantastic collection, with some real gems – and am looking forward to starting my online stroll around the museum this Monday, 12 February with a talk entitled Renaissance Rediscovered. This name is derived from the gallery’s own title for the refurbishment of the rooms housing the earlier parts of their collection. One of the things we will consider is how appropriate it is, particularly as I will start with works from the 13th and 14th centuries, which would be counted as medieval, rather than renaissance, according to most accounts. We will look in detail at the most significant paintings, while also discussing the value of works which in other situations we might overlook. This exploration will continue the following week with The High Renaissance, or, to be more precise, with works from the 16th Century. I will then take a break from the Walker to visit the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, and their exhibition Victorian Radicals (the Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts Movement, 26 February) before heading down to London, and Tate Britain, for Sargent and Fashion (4 March).

I wasn’t sure which of the Walker’s many treasures to write about today, and then realised that one of the paintings is actually on loan from the National Gallery: it’s the central panel of a triptych of which the Walker owns the wings. It makes sense to look at it in detail today, as this will allow me to spend more time on the wings on Monday. Another reason for writing about this particular image is that Lent starts on Wednesday (yes, it’s Shrove Tuesday, or Carnival, next week). Three years ago, in 2021, we were in lockdown, which meant I had the time to write a post every day during Lent. Each post looked at a single detail of a single painting, thus gradually building up a fuller understanding of it – without initially knowing what that painting was. As it happens, it was in many ways similar to today’s example. You can start following that, if you feel like it, by clicking on the word Lent…

This is not the prettiest painting. Indeed, it is one of the more grotesque works that I’ve written about, but art is not only about beauty, it is also about truth: the grotesque elements of this image say a lot about the cruelty of the acts performed over Easter, and speak to the suffering of Jesus. This is not Charles Wesley’s ‘Gentle Jesus, Meek and Mild’, even if he does appear remarkably at peace, despite everything. The cross on which he is crucified is planted in the centre of the painting, his figure placed frontally towards us. His mother, the Virgin Mary, and apostle, St John the Evangelist, stand at the foot of the cross in what, by the time this was painted, had long been their traditional places. Mary is on our left and John, our right, under Jesus’s right and left hands respectively. There is more space around these three main figures than anywhere else, and their pure bold colours – blue for Mary, red for John, and pale, naked flesh for Jesus – make them stand out from the crowd. They are isolated in the midst of what is otherwise a riot of forms in movement, of rich, patterned colours, and bold emotions. There is almost too much to look at.

You could argue that Jesus’s unique being – both fully God and fully human, two natures in one being – is expressed by the placement of his body. Above the waist his background is the sky, the ‘home’ of his Father in Heaven. Behind his legs we see the earth, and the impinging human figures. His loin cloth flutters above the horizon like a low flying cloud, the tonal values close to those of the distant mountains, rendered pale by the aerial perspective. He is framed by the sky, the open space around him allowing him to be seen more clearly than anyone else, and isolating him from the noise and activity with which the painting is otherwise filled. This space is created by the valley sloping down between the hills to the left and right, the line of the horizon echoing the curve of his arms. The hills on either side also connect the two thieves to the world with which they were so nefariously involved. They are traditionally disposed, with the Good Thief at Christ’s right hand, and the Bad at his left. Even if they do not have the ‘signifiers’ which in other paintings can help to identify them, there are subtle differences in the way they are depicted which confirm that the hierarchy of ‘right’ and ‘left’ – from Jesus’s point of view – is enough to tell us which is which.

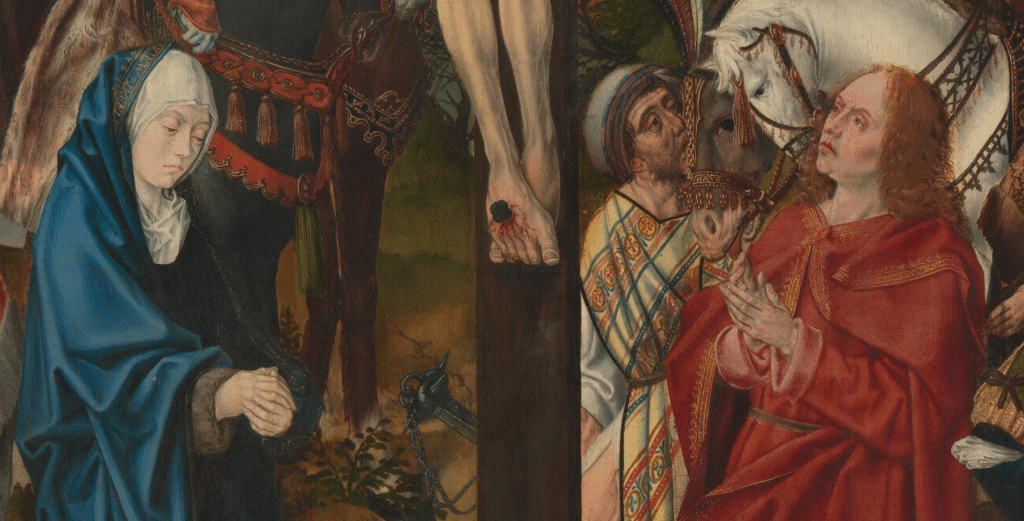

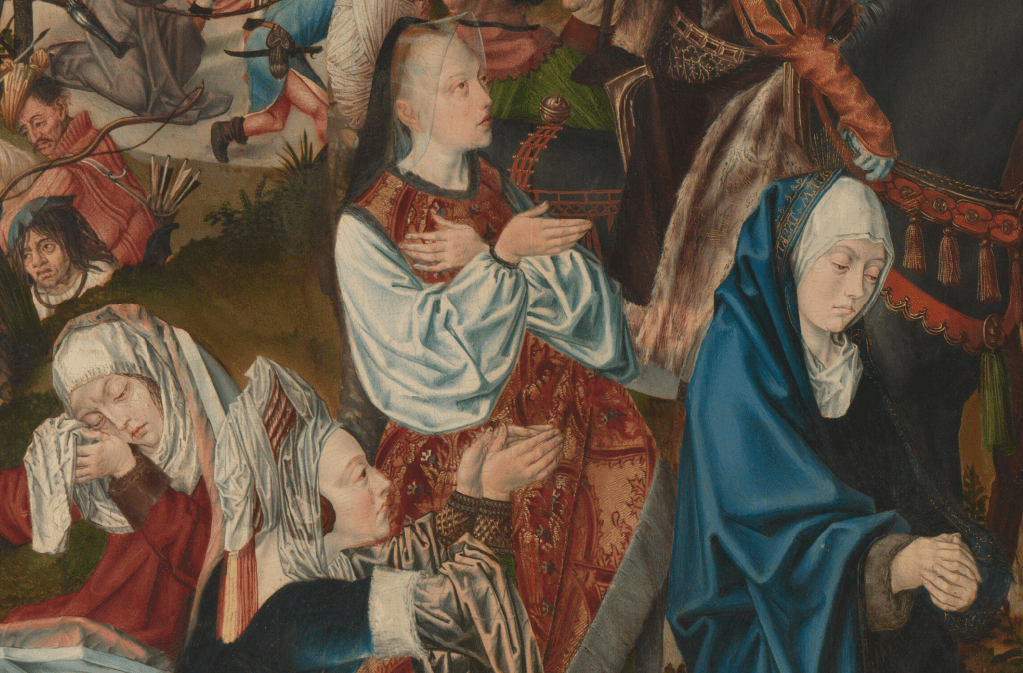

It is better to be at the right hand of God, particularly as regards the Last Judgement (the damned will be on his left), and although the Virgin and Evangelist are both assured of their salvation (well, Mary has no sin, so does not need to be ‘saved’), her placement on Christ’s right tells us that her status is higher than that of John, however close to Christ he might be. Both their verticality, parallel to the cross, and their location directly under right and left hands, tie them to the figure of Christ. Otherwise, the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ are in their respective places. Mary, at Christ’s right, is flanked by three holy women, all of whom were also called Mary. In the left foreground the diagonal formed by the kneeling woman continues through the fur hem of her standing companion, this diagonal leading our attention towards Jesus on the cross. John, at Jesus’s left, is surrounded by reprobates: soldiers, and others bent on Christ’s destruction. Although this side is more disordered, there is also a more subtle diagonal, formed by the hilt of the sword, and the back of the crouching man who wears it right in the bottom corner (this will be clearer in a detail below). The standing soldier, whose right arm holds onto an angled spear in an exaggerated gesture typical of the Master of the Aachen Altarpiece, also acts as a repoussoir: with his back to us he is looking into the painting, which encourages us to do the same.

John’s upward gaze also encourages us to look towards Jesus. His eyes are red with sorrow, his hands uncertain, at a loss what to do. Mary looks down, her grief contained, her pale and perfect complexion a reminder that, free of original sin, she will not age: at the very least she must be forty-eight by now (the age she was assumed to have been). You may be able to see the gold decoration of the hem of her cloak as it crosses her white headdress, and if you can, you may just be able to see that it includes an inscription: ‘stabat mater‘. This was the title of a 13th century hymn, and on its own it means ‘the mother was standing’. This only really has its full impact in the context of the phrase as a whole: ‘the sorrowful mother was standing by the cross from which her son was hanging’.

So much of what we see is derived from the bible. In the Gospel According to St John, Chapter 19, verses 25-27 it says,

25 Now there stood by the cross of Jesus his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene.

26 When Jesus therefore saw his mother, and the disciple standing by, whom he loved, he saith unto his mother, Woman, behold thy son!

27 Then saith he to the disciple, Behold thy mother! And from that hour that disciple took her unto his own home.

Not only does this explain the presence of the Virgin and St John at the foot of the cross (if not their exact positions), it also gives us the identity of two of the other Maries – the Virgin’s sister (Mary Cleophas) and Mary Magdalene. In Mark 15:40 we read,

There were also women looking on afar off: among whom was Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James the less and of Joses, and Salome.

This ‘Salome’ is completely unrelated to the daughter of Herodias who danced for Herod. The woman we see here is usually called Mary Salome. Like Mary Cleophas (who was identified as ‘the mother of James the less and of Joses’) she was often said to be a stepsister of the Virgin. Together with Mary Magdalene, they are the three Maries who are often seen at the Crucifixion, and later, at Christ’s tomb. Without inscriptions bearing their names it is not always possible to tell which is which, although Mary Magdalene often carries a jar of precious ointment, her main attribute. Here, though, she does not. However, she does stand, giving her a higher status (and making her more prominent, more on a level with the Virgin and St John), and she also wears the most elaborate and expensive clothing. Although Christian myth implied that she renounced her worldly past on meeting Jesus, for artists it was important to retain this display of finery, if only to help us identify her.

Clothing is also significant to define the character of the people surrounding St John. Apart from anything else, there is too much leg on display: the man in the splendidly patterned yellow robe at the left edge of this detail reveals a lot of thigh as his leg extends from his split skirt, while the soldier with his back to us reveals his calf. In neither case would this be deemed appropriate, which tells us that these are not respectable people. Facial features are also telling: the distorted, wrinkled, and scarred faces were thought to reveal the inner person, as ugly on the inside as they are without. The inelegant postures do the same. In this regard, the confusion at bottom right deserves closer attention.

In the foreground we can see something I haven’t seen before. In paintings like this, it is not uncommon for the cruel, even evil, to be mocked, and often it is as if the slovenly soldiers have allowed their ‘trousers’ to fall down, thus rendering them ridiculous, and taking away their power. Here, however, the man appears to have rolled up his ‘trouser leg’. His right calf is clad snugly in blue hose, a straight seam running from behind the knee down to his heel. However, the equivalent left leg of the hose has been peeled off, it seems, and the lower end pinned up to his waist. However, it is still attached to the red and black striped sections, decorated with a pattern of a gold knotted chord, with cover his thighs. We can see that his calf is ridged with varicose veins, and his ankle or shin is bandaged – which might explain why he has looped up his hose. Whatever the precise implication of this injury, there is surely a lack of decorum here, someone who is not dressed respectably, and so someone we need not respect. The same is true of the man crouching on the ground to the right. He is actually kneeling, with one foot crossed over the other. He bears his weight on his bent left arm, the gold-lined sleeve rolled up to reveal a black undersleeve, and in his right hand he holds a pair of dice. His companion, a particularly gormless looking man in a striped tabard, pulls at a black mop of hair belonging to a third man, who is bending over towards us, on one knee, with the more upright leg visible and clad in red hose. It’s a complex arrangement of figures which is hard to read, but they are the men mentioned in Matthew 27:35 –

And they crucified him, and parted his garments, casting lots.

These men are a fulfilment of Psalm 22:18 –

They part my garments among them, and cast lots upon my vesture.

Above them, at the top of the painting, we see the Bad Thief, in the most remarkable, contorted pose. This extreme stretch, with body arched and taut, and arms and legs twisted, confirms his identity, and reflects the convoluted wickedness of his soul. The flesh pulls against musculature and ribs, and we cannot see his face, just glimpsing the underside of his chin, his nostrils and a hint of an eye. The jagged, discoloured loin cloth adds to the sense of unpleasantness, even discomfort. This pose is echoed in the background as part of the next episode in the story: Jesus is taken down from the cross by Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, while John supports the Virgin – who has collapsed to the floor in her grief – and two of the Maries look on. The pose of the Good Thief here is also an echo of the main image.

His body is also contorted, with the arms and legs wrapped in different directions around the cross. However, I can’t help thinking that he looks more tranquil: his body is more relaxed and not wracked with either tension or guilt. On being told by Jesus that they will see each other in Paradise he is assured of his own salvation, and his face appears both rested and serene. Even the loin cloth is an indicator of his serenity – particularly when compared to the jagged energy of the Bad Thief’s greying fabric. His hair is curiously dark (it is usually shown the same light brown as Jesus’s), and oddly long, falling over his face in what seems to me a peculiarly 21st-century way. In the background we see another image of Christ, some way behind the Good Thief’s feet.

This is an earlier episode from the story, the Via Crucis, or ‘Way of the Cross’. Still wearing the purple robe and crown of thorns with which he was dressed in mockery by Pilate’s men, Jesus is carrying the means of his execution on the road to Calvary, the place where he will be crucified. He is still mocked and beaten. A rope is tied around his waist. One end is held by a man in a blue smock with red leggings who leads him forward, the other end by a man in striped blue hose and armour who kicks him as he falls. There are two other soldiers, one of whom prods Jesus with a long stick or spear. The other stretches back his right arm as if preparing to strike.

The two small, additional scenes form a continuous narrative leading from the background on the left (the Via Crucis) to front centre (The Crucifixion), and then to the background again (The Descent from the Cross), almost as if a camera were panning across and zooming in to the most important part of the story. However, the painting was originally more complex than this. As I said at the top, The Crucifixion is currently on loan to the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. They own the two side panels of the triptych, and together they help to complete the story. When they were closed, another, less usual narrative could be seen, not only brilliantly painted but also surprising in content: we will look closely at these outer panels on Monday.

In the detail above I said that Jesus was on the road to Calvary, a place name derived from the Latin word calvaria, meaning ‘skull’. It has another name, which is actually the same: ‘Golgotha, that is to say, a place of a skull’, to quote Matthew 27:33. The skull in question can be seen in full view, front and centre at the base of the cross.

In legend this was the skull of Adam, the first man, and the first to die. On his grave was planted a shoot of the tree of life, which was eventually used to make the cross on which Jesus was crucified, the cross being planted in exactly the same place as the tree from which it was hewn. No, none of this is in the bible, but it was widely believed anyway. In the painting it gives the Master of the Aachen Altarpiece an excuse for a glorious still life detail. The skull is expertly depicted, and is flanked by a caterpillar and a frog, neither of which is entirely of the earth. The frog started life as a tadpole, and regularly returns to the water. It is somewhat slimy and not necessarily pleasant, and was often related to death, decay and even the forces of evil (think of the witches in Macbeth, with their ‘eye of newt and toe of frog’). The caterpillar, worm-like, might seem similarly ‘unpleasant’, but at least it will be redeemed: it will ‘die’, and enter a tomb – its cocoon – before emerging as a butterfly, far more beautiful and destined for the sky. This death and resurrection into a superior, heaven-bound form is not only related to the death and resurrection of Christ, but of mankind in general. From being gross, and earthly, we will transcend our mortal remains to become pure spirit: the butterfly was a symbol of the human soul. In Ancient Greek ‘butterfly’ and ‘soul’ were even the same word: psyche.

On either side of the skull are beautifully naturalistic renderings of different plants. From left to right they are – with different degrees of certainty – common knotgrass (Polygonum aviculare), prickly sow-thistle (Sonchus asper), oleander (Nerium oleander), maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes) and plantain (Plantago major). There’s a nice dandelion further to the right of this detail, too. Whatever the symbolism (and it varies, from the results of sin to the possibility of salvation), the Ecologist reliably informs me that they are all – with the exception of the more Mediterranean oleander – plants that grow in settings which have been disturbed by humans. This very specific ecosystem has no symbolic value, nor would the concept have been understood by the artist. Nevertheless, it is an example of superb observational skill, and an embodiment of the interest in the world around us which was an essential element of renaissance thought. You could argue that the observation of the humans in the painting is not of the same order – but how ‘human’ are they? The heightened depiction of their grotesque behaviour is, perhaps, an accurate rendition of their inhumanity. The outer wings of the triptych constitute similarly astute observations of church practices of the day – but we will have to wait until Monday to think about that.

Dear Richard

I have really enjoyed your on line talks over the last year, whether you do them direct or through artscapade (which has the bonus for us of not needing to see them live). You always give us a new way to look at the work.

Following your talk I went to see the Pesellino; every bit as good as you said and stunning in the flesh as it were. I watched your talk on catch up but the question I wanted to ask was about the use of silver leaf when it is going to tarnish to black. Why do it since the effect is not going to last, unlike gold? Sorry if you answered this after I switched off the Q and A but what was the reason since they must have known what would happen? Was it because they liked the eventual effect; they assumed someone would re-do it at some future date; or they didn’t care since they were looking to demonstrate wealth and craft not permanence? Or some other reason?

It’s not just Italy; I have seen lots of examples including icons of blackened silver so it must have been fairly common. If you could enlighten me, that would be great

All the best

Jonathan Tross

LikeLike

Hi Jonathan,

Thank you – I’m so glad you’ve been enjoying the talks!

Apologies for my delay in replying: I’m in too many places at the moment.

Often the artists – and their patrons – were interested in ‘immediate impact’ i.e. what the work looked like when they were first created. It takes a while for silver to tarnish, and so they would have looked impressive for some time. By the time the initial lustre had balckened, the patrons might have decided to redecorate anyway, and cassoni, or similar items of furniture, would have gone from being visually impressive to ‘merely’ practical objects.

Silver leaf was also used on altarpieces, of course, which one might expect to have had a longer life – although they were often replaced too. I remember reading a while back that artists sometimes had contracts which allowed for the replacement of silver leaf, though, and that it would be renewed. Annoyingly I can’t for the life of me remember where I read that. However, once the techniques of naturalistic depiction had been fully developed, the silver leaf was sometimes painted over with grey-to-white paint that looked like shiny silver. However, that overpainting is likely to be removed by contemporary conservators…

Icons quite often have revetments, a form of cover, which reveal the face and hands of the saint. These are often silver, which has tarnished. That could be cleaned relatively easily, but sometimes the black patina is seen as a sign of respect over the ages, I suspect, making the image more venerable. But that’s not really something I know much about.

I hope that goes some way towards answering your queries – but if I bump into any art historians or conservators I may just ask them.

All best,

Richard

LikeLike

Thanks Richard. Th

LikeLike