Netherlandish or French, The Madonna and Child with Saints Louis and Margaret, about 1510. The National Gallery, London.

My first talk about the newly refurbished Sainsbury wing, this Monday, 30 June at 6pm, is entitled Opening up the North. There are various reasons for choosing this title, which I will discuss during the talk itself. If you click on either of those two links you can book for that talk on its own. However, up until 6pm on Monday you will still be able to book, on the next two links, for all three of the Three Sainsbury Stories at a reduced rate – which admittedly equates to what has been the price up until now. The other two talks will be At home in the Church on Monday 7 July, and In Church and at Home the following week. I shall then head off to the northern extremities of the British Isles for a holiday, before returning to revisit Duccio’s Maestà with a repeat of my National Gallery ‘in-person’ lecture, Seeing the Light – which I will expand a little – on 4 August. For any other dates which might arise, do keep an eye on the diary – although I might add that, by 4 August, I will already be in rehearsal for two plays at the Sidmouth Summer Play Festival, which seem to confirm my type-casting as either a police detective or a vicar… But before we get there, let’s think about Opening up the North – one of the things that the National Gallery’s latest acquisition certainly does. Have a good look at it before reading further! I make no apologies for this being one of the longest posts I have ever written, it’s that intriguing, and I’m indebted to the entry on the National Gallery’s website, which says some of the following far more concisely!

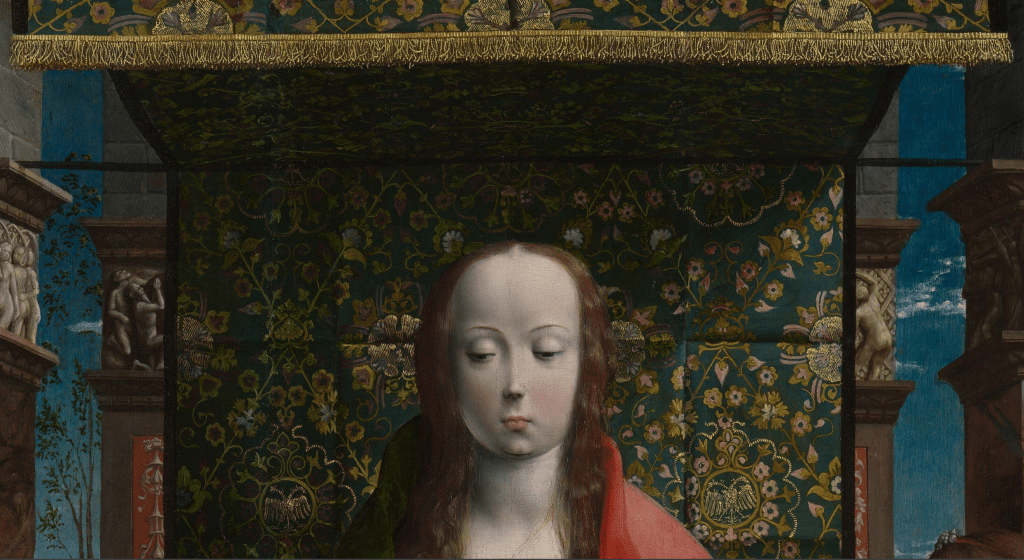

I was first alerted to the NG’s acquisition of the painting by one of you, wanting to know more about it: thank you! That’s one of the reasons why I’m writing about it today. Well, that, and the fact that, initially, I was equally baffled! However, the more I have looked, the more I have become intrigued, the more I appreciate the acquisition – and the more I like the painting. I don’t know what first grabs your attention, but I was initially shocked by some of the awkwardness, ugliness and crudity – and that is precisely what I have come to love about it. It’s not what I expect of the Northern European Renaissance, and that is exactly why I think it is such a good acquisition: it opens up our idea of what the artists could do. Maybe, at first glance, you realised what an entirely traditional painting it is: a Madonna and Child Enthroned with two angels (one on either side) and two saints (one on either side). Within an open loggia, with a row of square columns on either side, a richly embroidered cloth of gold is hung to create a canopy which defines Mary’s seat as a throne, and therefore confirms her status as Queen of Heaven. Although seated, she is higher than the other characters, and steps lead up to the throne. However, the steps are mere wood, and there is what is probably the most grotesque monster I have ever seen lurking front and centre.

However, at the top of the painting everything appears calm, even placid. Mary sits formally, facing front, a flower between left thumb and forefinger, and the Christ Child sat naked on her right knee, supported by her right hand. He looks towards our left, either at the angel doing something strange with its mouth, or the royal figure who looks across the pictorial field, almost as if he is unaware of being in the presence of God. On the right a woman has her hands joined in prayer, holding a cross, with a dove sat calmly on her shoulder, for all the world like the holy antithesis of Long John Silver and his parrot. Behind her an angel holds a book. The colonnades stretch back into the space, with the capitals – or are they mini-entablatures? – carved in high relief, and forming diagonals which lead our eyes towards the Virgin’s face.

That face has the most perfect complexion, pale, as it was believed befitted someone pure, and without blemish: immaculate, like the Virgin herself. I know, the proportions are slight odd, but a high forehead was considered beautiful – so this must be the most beautiful – as was a long, slim nose with a petite rounded end, and a narrow, cupid’s bow mouth. The light falls from above and from the right, although Mary’s right jaw (on our left) is also illuminated by reflected light. It can only have come from her son. Her eyes are lowered, solemn, as she is aware of what will pass after another three decades or so: his crucifixion, references to which abound in the painting. The cloth of honour is one of the most delicately embroidered I have seen, with stylised flowers, leaves and stems, and a pair of double-headed eagles in roundels, one on either side. They bring to mind the Hapsburgs and the Holy Roman Empire. A pole spans the gap between two of the columns, and the cloth of honour has been hung over it. There must be another pole further forward from which the fringed end of the fabric hangs, thus making a canopy appropriate for the royal presence. We can’t quite see where it is hanging though, which might suggest that the painting has been cut down – but apparently not: underneath the frame there is unpainted wood on all four sides of the image: this is the full extent of the painting. The result is that the canopy is pushed forward towards us, thus bringing us closer to the holy figures. The detailing is so precise that we can see folds in the fabric – a horizontal at the level of Mary’s eyes, and a vertical on either side of her head, going down to her shoulders. They make a cross on both sides – which reminds me of the two thieves crucified on either side of Jesus. The horizontal fold also connects two of the relief carvings: people in prayer, looking up to God, on our left, and the back of a naked boy looking down on our right.

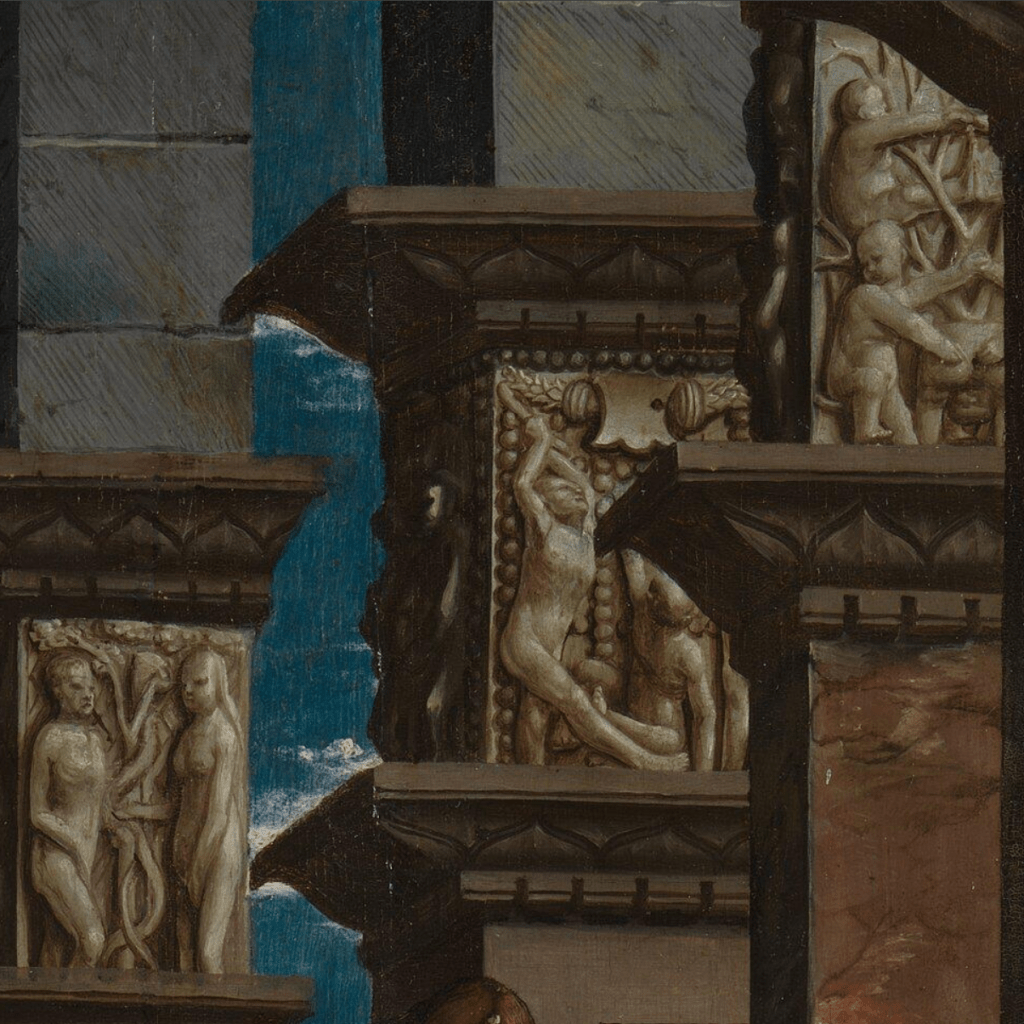

I have suggested that these might be capitals, but the more I look the more I realise that they are not high enough up the columns to be capitals. Each column is treated as a pier (a supportive mass of masonry) with its own entablature, which suggests that the reliefs are remarkably short friezes below the cornice. Each is intriguing, and some can be easily interpreted. Naked boys are playing on the far left – one is blindfold, two others hug or fight. On the next column the friezes focus on grapes. On the side facing us is the Drunkeness of Noah. The one good man survived the deluge (with his family), grew vines, made wine, got drunk and revealed his nakedness: one of his sons lifts his elbow above his father’s head and covers his eyes to avoid seeing the paternal shame. The implication of this story is that even the one good man was still in need of redemption. The side which faces into the space shows two men carrying a pole from which is hung the most enormous bunch of grapes. These are the Grapes of Canaan – a story from Numbers 13:21-24 in which Moses sent spies into Canaan. It truly was a fertile place, and the grapes were just some of the evidence that this, a land that ‘floweth with milk and honey’, really was the promised land.

On the other side, Adam and Eve stand under the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, with the serpent snaking up between them: The Fall. Further forward, a man lifts something while another cowers beneath: Adam and Eve’s sons, Cain and Abel, and the former killing the latter. And if these two scenes didn’t persuade you that mankind was in need of redemption, the last will: a group of naked boys are playing around in a barren tree, with one of them bending over and peering between his knees to show you his bottom. Two of his friends are pointing at it. This is not what I meant by ‘crudity’, when I used the word before, but it is remarkably rude. It reminds me of some of the grotesque and low-comedy carvings you get on misericords, the underside of fold-up chairs that monks and priests could perch on in many European churches and cathedrals during the long religious services. I think that it is there as light relief after the murder of Abel – something we can snigger at, perhaps, but learning through laughter. It belittles those who misbehave, whilst our enjoyment of it might also bring us up short in the presence of God, guilty about our own enjoyment of the bawdiness. Before we move on, just look at the stonework above these friezes, with the careful, insistent diagonals showing us how the masons finished the blocks at the top of the columns, rougher than the more smoothly dressed surfaces below – but don’t forget that we are in need of redemption.

After all, redemption is what the painting is about. The Christ Child may be distracted by the curious behaviour of the angel on the left, but that wouldn’t seem to excuse his cruel treatment of the bird he is holding. However, you have probably seen this bird in other paintings: it is a goldfinch. The red patch on its head is supposed to have come from Jesus’s blood, when one of the birds either ate a thorn from the Crown of Thorns – or, in another version of the story, pulled one of the thorns from Jesus’s forehead. It is a symbol of Christ’s passion, and in this painting Jesus manages to show that, far from fearing his own death, he has it in hand – quite literally. He can take our sin upon himself and can even turn his own death on its head. Notice how the bird casts a dark shadow on his thigh, with another shadow – that of Jesus’s own right arm – forming a diagonal which leads to the goldfinch’s head. Another reminder that this painting is about redemption is the flower which the Virgin holds. The Ecologist has let me know that it could be Honesty or a single Stock (i.e. not the horticultural ‘double’ variety), but whatever it is, the flower is white – a symbol of purity – and cruciform. This means, basically, that it has four petals in a cross formation. There are no prizes for guessing the symbolism.

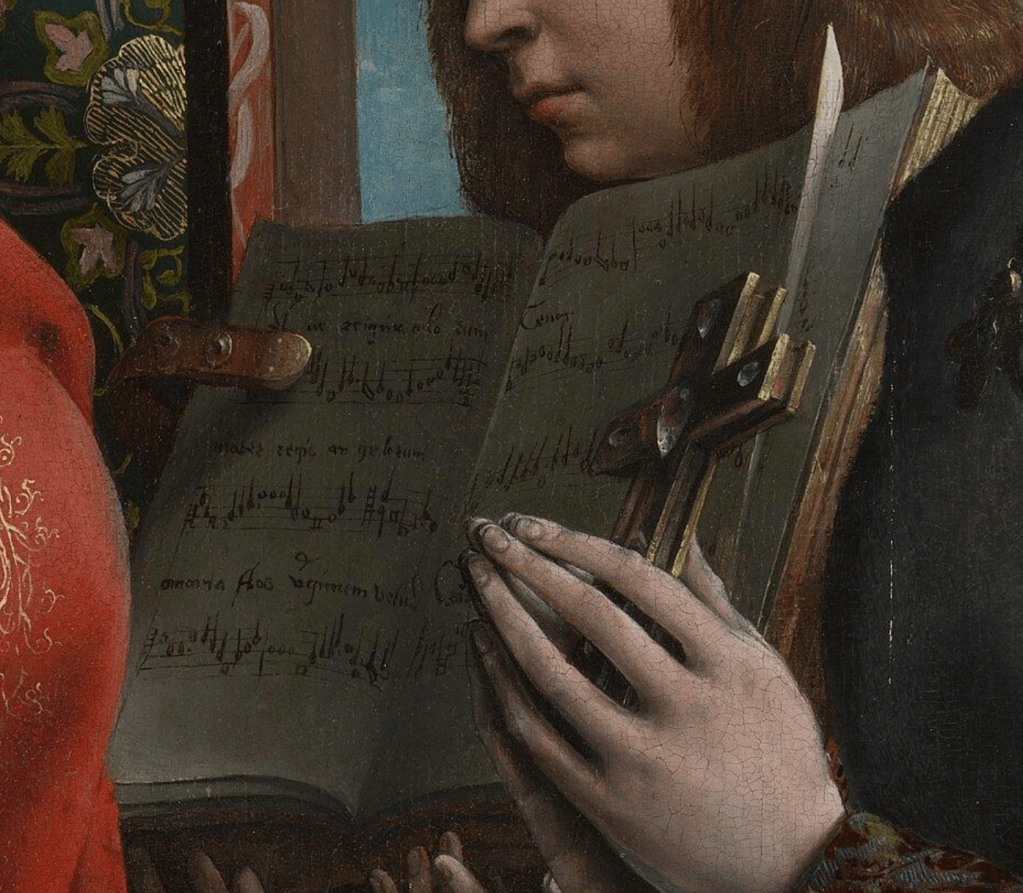

The angel on the right holds an open book – a music book – and although the music looks accurate – with the correct symbols and staves for music of the time – it is not a transcription of anything known. However, the words are. This is a medieval hymn, Ave Regina Caelorum, Mater regis angelorum (‘Hail, Queen of Heaven, Mother of the King of Angels’). The music is, of course, a clue as to what the other angel is doing.

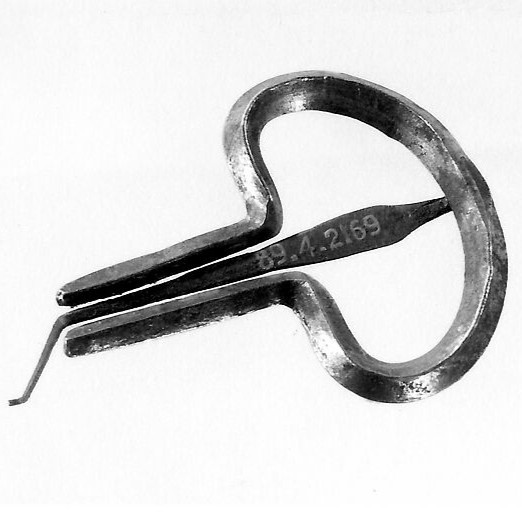

He’s playing a musical instrument, a mouth harp, or jaw harp (you might know it as a Jew’s harp, although the term has fallen out of favour because there doesn’t seem to be any connection with either the religion or the people – the instrument originated in China). To quote one website I have found, “To play, position it between your slightly parted teeth and lips, ensuring the tongue [of the instrument!] is free to vibrate. Pluck it gently with your finger while shaping your mouth cavity to control pitch and tone. Your mouth acts as a resonator, so subtle breath control and movements of the tongue, cheeks, and throat help create varied sounds.” It is remarkably rare to see one in the world of art, although it is played by an angelic musician on the mid-14th century minstrels’ gallery in Exeter Cathedral, and by one of Dirck van Baburen’s ‘young men‘, in a painting from 1621 in Utrecht.

Jesus appears to have been distracted by the curious twanging sounds it makes, and this has stopped him torturing the goldfinch, or paying attention to the two visitors to his court – or us, for that matter. He sits on a white cloth, which is undoubtedly a reference to the shroud: notice how the shadows of Christ’s legs fall over the extended folds of the cloth. It is also reminiscent of the white cloth spread over the altar during mass, or for that matter, the corporal, another white cloth, which is also placed on the altar, as a fitting place for the chalice (containing the wine, the blood of Christ) and the paten (with the host, the body of Christ). In this painting Christ’s body and blood are also set on a white cloth – in the person of Christ himself…

On the left, the specific details of the man’s face suggest that this could be a portrait – but if it is, the subject appears in disguise as a saint. Although there are no haloes – and the angels have no wings – we need not doubt that they are all holy. Why else would they be there? He is a king – a fact emphasised not only by his crown and sceptre, but also by the ermine cape around his shoulders. His deep blue robes are embroidered with gold thread to form a pattern of large fleur-de-lis. The robes have the colours and emblem of France. This is St Louis – but not the Franciscan St Louis of Toulouse, who would only have dressed like this had he not abdicated the throne of Naples to become a Franciscan (in which case he may well not have become a saint): there is no evidence of the Franciscan order here. This is St Louis of France, King Louis IX (1214-1270), collector of relics such as the Crown of Thorns, which he housed in the Sainte Chappelle in Paris, built specifically for this purpose. More relevant is the fact that he granted the Premonstratensian order the right to use his fleur-de-lis in their coat of arms: it is no coincidence that this altarpiece was first recorded in the Premonstratensian Abbey in Ghent in 1602. We don’t know that it was painted for this Abbey, but it seems highly likely. Apart from anything else, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was born in Ghent in 1500. At the time his grandfather, Maximilian I, was Emperor, and Maximilian was the one who really cemented the use of the double-headed eagle as a symbol of the empire – which could explain its presence on the cloth of honour. The painting was probably painted around 1510: there are very specific features which help to restrict the image to what is admittedly quite a broad range of dates.

St Louis is wearing the French Order of St Michael. The badge hanging from it shows St Michael himself defeating the devil. The Book of Revelation 12:7 says that ‘Michael and his angels fought against the dragon’ – who is then identified in 12:9, as ‘that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world’. The chain, which has double knots on it, was altered by Francis I in 1516 – suggesting a date before this for the painting. In addition, dendrochronology tells us that the panels on which it was painted date, at the earliest, from 1483. It’s a 33-year timespan, which isn’t very specific, but stylistically 1510 makes sense. However, we have no clue as to who might have painted it. Some of the stylistic features are French, whereas the panels are made of Baltic oak, used by Netherlandish artists (the French used locally sourced oak) – and this does seem to have come from Ghent – so ‘Netherlandish’ seems more likely.

While the depiction of the chain and medal – the ‘collar’ of the order – is highly accurate, the sceptre which St Louis is holding appears to be entirely original. There are lots of figures squirming around, and the best suggestion so far is that it represents a detail from the Last Judgement. This would make sense next to St Michael defeating ‘the dragon’, as St Michael is supposed to weigh the souls of the dead at this time. Again, it brings us back to the need for redemption. Without it, we would be one of these squirming figures being dragged down to hell. The collar and sceptre are entirely fitting for St Louis, King of France, but as yet there are few clues as to the identity of the woman on the other side of the painting. She holds a cross, yes, but then all female saints could. And she has a dove on her shoulder – which I’ve never seen before – but then so many of the saints were inspired by the Holy Spirit. The real clue is at the bottom of the painting.

This is undoubtedly the most hideous monster I have ever seen in any painting. Most devils end up looking cute and endearing (check out Bermejo’s, in Picture of the Day 5, or Andrea Bonaiuti’s in POTD 24), whereas this one is truly scary. It’s the teeth, I think, with three fangs coming down from the top and four from below, interlocking like some destructive machine. The teeth themselves are black and brown with dirt and decay, and emerge from raw, red gums. Even if it’s not clear on this detail, they are also strung across with streaks of saliva, which in the flesh (if not on a screen) are truly repulsive. And then there are the bloodshot eyes, the weirdly shaped ears and the pointy head. Even the neckless way the head joins the torso is unpleasant, with a scaly carapace and spotted wings adding to the effect. It creates such a contrast with the beautiful, and beautifully depicted, brocade of the woman’s cloak which falls across its wing, and even seems to emerge, just below her bent knee, from the monster’s back. But this is the clue! This is St Margaret of Antioch, a Christian martyr who was thrown into prison, and subjected to many hideous tortures. According to the Golden Legend, which I’m quoting here in William Caxton’s version from 1483,

And whilst she was in prison, she prayed our Lord that the fiend that had fought with her, he would visibly show him unto her. And then appeared a horrible dragon and assailed her, and would have devoured her, but she made the sign of the cross, and anon he vanished away. And in another place it is said that he swallowed her into his belly, she making the sign of the cross. And the belly brake asunder, and so she issued out all whole and sound. This swallowing and breaking of the belly of the dragon is said that it is apocryphal.

It may well be ‘said that it is apocryphal’, and yet artists loved to paint it! She very often holds a cross, as if she has cut her way out with it, and she certainly holds one here. But what about the dove? Well, that’s there in the Golden Legend too, though this is the only time I’ve seen it. After the dragon, Margaret was subjected to even forms of torture,

And after that, they put her in a great vessel full of water, fast bounden, that by changing of the torments, the sorrow and feeling of the pain should be the more. But suddenly the earth trembled, and the air was hideous, and the blessed virgin without any hurt issued out of the water, saying to our Lord: “I beseech thee, my Lord, that this water may be to me the font of baptism to everlasting life.” And anon there was heard great thunder, and a dove descended from heaven, and set a golden crown on her head.

The dove has remained, but the ‘golden crown’ is not what you might have thought – at least, not in the painting.

Margaret’s hair has been plaited together with threads strung with gold sequins, and the plaits piled on and around her head. There is also a garland of flowers, including daisies, placed delicately round her coiffeur. In French, daisies are marguerites – no doubt a pun on her name. Above the dove’s head, to the right of Margaret’s piled up hair, the column is decorated with a red panel with white relief sculptures – what is known as a candelabrum. At the very top are two swans with their necks intertwined. Given that the main feature of the Ghent abbey’s coat of arms was a swan, this would seem to confirm that the painting originated there. At the left of this detail you can also see the beautifully embroidered (for which read ‘painted’) double-headed eagle.

So the dove confirms that this is St Margaret, although the dragon would have been enough. I wanted to return to this detail, though, to think about the steps of the throne: another ‘I have never’. In this case, I have never seen steps to Mary’s throne made from ‘raw’ planks of wood. Sometimes the steps might have been wooden, I suppose, but painted to look like marble, but in this case, as a royal throne, the steps are remarkable crude in their construction. Unpainted, undressed (there is no rich fabric laid over them), and with simple nails driven into them, there is no attempt to disguise the simplicity of the making. Three nails are visible on the lower step, and two (one partially hidden) on the upper. This basic construction might be a symbol of humility, but there is an unmistakable reference to the crucifixion too. In the open, well-lit space beneath Jesus, the reference is not only to the making of the cross, but also to the three nails driven through his hands (one nail for each) and feet (one nail for both). The contrast with the ermine and royal blue of Louis’ cloak couldn’t be more striking. Again, we are right there, so close to the image, given that the bottom of the cloak, of the central step, and of the dragon are cut off by the frame. Again, like the canopy at the top, this is the original extent of the painting. We are pushed close to these holy figures – and to the most unholy – so that there is no possibility of escape. The threat of damnation, and the possibility of redemption, are opened up to us as the unknown artist of this remarkable painting expands our expectations of what the art of Northern Europe can be.

Sent from my iPad

LikeLike