Fra Angelico, Christ Glorified in the Court of Heaven, about 1423-24. The National Gallery, London.

I have just returned from my first visit to the glorious exhibition Fra Angelico in Florence. Spread across two venues – Palazzo Strozzi and San Marco – it is the most comprehensive collection of works by this Dominican master that have ever been brought together. The curators want us to reassess the way we appreciate his works – and they are entirely successful. Since the 19th Century Fra Angelico has been seen as clinging on to the tails of the medieval (and, as a result, he was very much in vogue post-Pre-Raphaelites), but he now emerges as one of the great innovators of the Florentine Renaissance, up there with Masaccio who was, as it happens, slightly younger than him. To understand his work fully, and to put it in the appropriate contexts – both the artist’s life and faith (which were pretty much one and the same thing) and also the artistic developments of the time – I have planned four talks. The first, this Monday 6 October, is called The Melting Pot, and will reflect the remarkable range of styles and influences current in Florence in the first quarter of the fifteenth century. It will build, as much as anything, on the San Marco section of the exhibition, and on the first room in the Palazzo Strozzi. In addition to the earliest paintings by Fra Angelico, there will also be works by Ghiberti, Masaccio, and Gentile da Fabriano, not to mention an artist from another religious order, Lorenzo Monaco (the clue is in the name). After I’ve been back to Florence to see the exhibition again, I will return to continue the series with As seen in the Palazzo Strozzi (20 October), which will walk us around the remainder of this, the larger part of the exhibition. Fra Angelico 3: At Home in San Marco on 27 October (going on sale after the first talk, with a reduced price for those who have attended that one) will take us back to the Priory to look in detail at the many frescoes which the artist and his workshop carried out in the friars’ cells, and in the communal spaces. Finally, Fra Angelico 4: Students and Successors (3 November) will look at the artist’s work after he left Florence, and at his heritage. This will include not only the students and assistants with whom he worked, but also some ‘official’ Dominican artists from subsequent generations, including Fra Bartolomeo and Plautilla Nelli – arguably the first successful woman who worked as a painter in Florence.

Beyond that, I’m already looking to cover two exhibitions from the National Gallery (Neo-Impressionism and Joseph Wright of Derby), and three exhibitions of Loans to London (from the Barber, of a Vermeer, and a Caravaggio). But more news about them later – keep an eye on the diary, as I’m still juggling my dates! Today, though, I want to look at one of the National Gallery’s paintings by the hero of the moment.

There are actually eight paintings by Fra Angelico listed in the gallery’s catalogue, only one of which has made it to Florence. Five of them (see above) originally belonged together as the predella panel of one of his earliest surviving works: the San Domenico Altarpiece – painted for the high altar of the eponymous church in Fiesole, which is where Fra Angelico’s vocation and career are first recorded, and which remained his ‘house’ throughout his life. Because of its rich detailing, these five panels are hard to look at thoroughly in the National Gallery. It is, in its own way, encyclopaedic, and given that the individual figures are so small, it is all too easy to assess the amassed company of heaven, marvel at the multitudes, and move straight on without really looking. I’ve shown it to several groups, but don’t feel that I have ever done it justice. As a result, I think it’s time to slow down our looking, and look at each of the five sections individually. Well, one each for the first three weeks, and then two together for the fourth – using each text to introduce one of the talks. Although we read words from left to right it doesn’t make sense to approach the painting in this way. Instead, we will start in the middle this week, and then gradually work our way out.

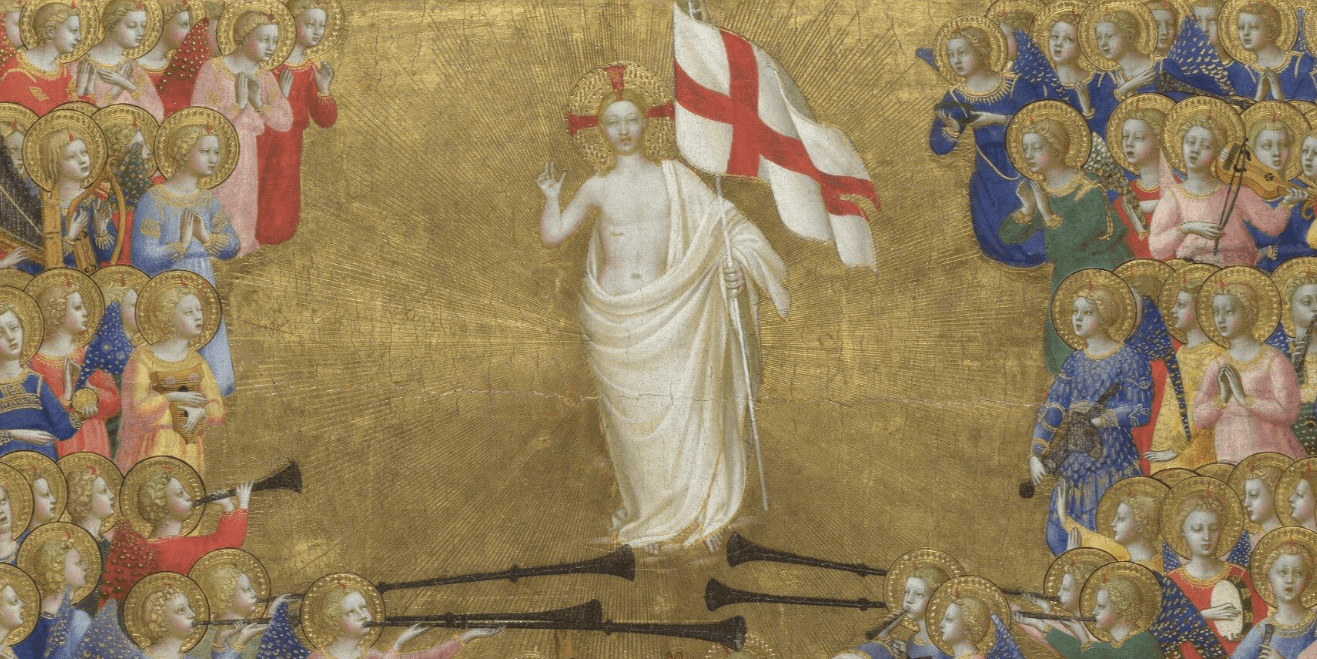

The title of the central section could equally well be the title for the predella as a whole, Christ Glorified in the Court of Heaven – but that will become clear as we work our way through the panels over the next month or so. Starting from this point we see Jesus himself at the centre of the painting, splendidly isolated against a golden background. He wears something akin to a white toga, its colour barely distinguished from that of his skin, or for that matter, the background colour of the flag he is holding – white. The flag also has a red cross, as does his halo. He is surrounded, at a discreet distance, by a vast number of figures dressed in what at first glance appears to be a multitude of colours, but which could be broken down to red, pink, green and blue, with a hint of yellow here and there. Precisely who they are and what they are doing will become clearer as we get closer. Remembering that the best place to be is at the right hand of God – the position of honour – we will start by looking at the top left corner of the panel.

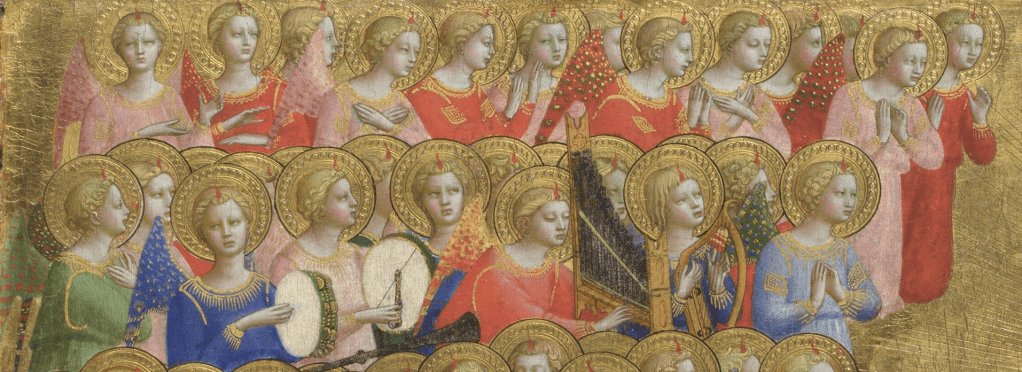

Every single figure has a halo, and every single figure has a pair of wings: these are just some of the angels. All of them also have a flame above their heads – something I would usually associate with Pentecost – which suggests to me that they are all inspired by the Holy Spirit. While there might not appear to be any way to distinguish these angels, the top row are all wearing red or pink, which implies that they are the Seraphim, the highest of the nine choirs of angels. Their name comes from the Hebrew word for ‘burning’, and they were considered by some authorities to be the only beings who could withstand the full glory of the deity. Isaiah describes them as being ‘above’ the throne of God, occupied in constant prayer and praising: ‘And one cried unto another, and said, Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of hosts: the whole earth is full of his glory’ (Isaiah 6:3). Thomas Aquinas – a leading Dominican theologian – considered them to burn with the love of God, and as Fra Angelico himself was a Dominican this is surely relevant. Looking from right to left you can see how one has both hands raised, one has the palms of his hands pressed together, and a third crosses his hands over his chest. As you keep going along the line you will see that these gestures are repeated: they are all associated with prayer. Fra Angelico went as far as demonstrating these acts of devotion in frescoes for the novices’ cells at San Marco, as we shall see when we get to Fra Angelico 3. Having said that, the two Seraphim at the far left appear to be practicing the hand jive – but then, dance has often been considered an essential part of worship (the National Gallery’s catalogue entry, to which I am indebted, suggests that most of the angels are dancing – but I’m not sure that I would go that far). The second row down in this detail has a wider range of colours, with the addition of green and two shades of blue. Several of the angels play musical instruments. From left to right I can see a tambourine and a tabor, beaten with a drumstick. There is also a portative organ (i.e. a portable organ – the right hand plays the keys while the left hand pumps the bellows) and a harp. The angels at far left and right repeat some of the gestures of prayer we have already seen.

If it is ‘higher’ status to be at the right hand of God, it is not at all bad to be at his left hand: at least you are close – unless you are a soul at the Last Judgement, of course, in which case you be be heading down to hell. The second most important group, then, is made up of the angels at the top on our right. They are all clothed in a rich deep blue – the blue of heaven – and represent the Cherubim. Thomas Aquinas associated them with knowledge – and so in some way, they are the ‘head’ as opposed to the Seraphim who could be seen as the ‘heart’. Having said this, different theologians – and artists – had different ideas, and as a result the colours with which they are represented can also vary. In this case the Cherubim echo the Seraphim’s constant prayer and praising – including the dance-like gestures with one hand held to the chest, and another indicating Christ: this gesture is repeated in some of the larger-scale figures in other altarpieces. Many angels have their mouths open – they are singing – and one, on the far right, looks up towards God the Father in the highest firmament. I’d recommend taking this opportunity to look at each angel individually, as it’s hard to spend the time doing this when you’re surrounded by the general public – and when there are another 2000 or so other paintings to look at in the Gallery. In the second row the angels sport a similar colour palette to the figures on the opposite side, although there is a figure strumming a lute whose robe shifts from yellow to green. Just to our left of him one of the number plays a viol.

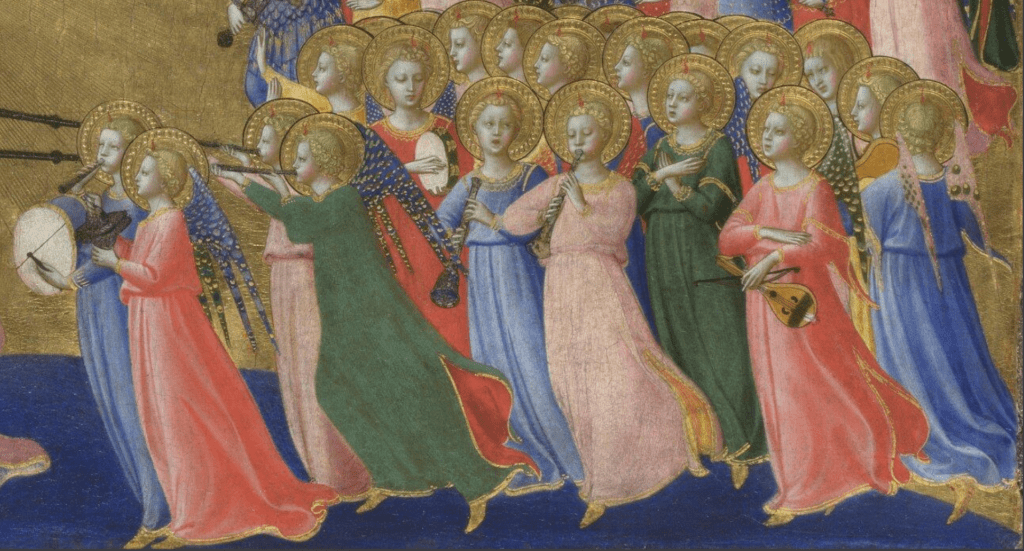

If we move back to the left of the painting, and down a tier, there is another colour shift in the figure on the far right. He is clasping a zither, and his robes are a combination of pink and yellow. This is a fabric in which the warp and weft are made from two different coloured threads – a shot silk, effectively – and the colour you see depends on the way the light is catching the fabric as you look at it. In paintings, this changing colour is described with the Italian word cangiante (‘changing’), and although it does exist down here on earth, in paintings it is especially associated with angels, as it tends to dematerialise the form and gives them an other-worldly air. Just to our left of this cangiante robe, one of the angels, wearing the deepest blue, holds an orb in his left hand. He could be a Dominion. According to the most common hierarchy, they were the fourth rank of angels – after Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones – and they helped to maintain order in the universe. However, although the orb is a common symbol for the Dominions, and we have already seen the Seraphim and Cherubim, Fra Angelico doesn’t appear to be concerned with the enumeration of all of the nine choirs of angels, as described by a number of different theologians, not to mention Dante (who some considered was a theologian anyway). In this painting it would be difficult to point out the Virtues, Powers, and Principalities, for example, or to distinguish between an Archangel and an Angel. I’ll have to try and do that with another painting in another post on another day… There are more musicians here, though, with the angel on the far left blowing a long trumpet picked out in what is now tarnished silver leaf (the organ pipes in the row above were also made of silver). In the centre of this row the angels playing the harp and lute look at each other, as if to keep in time, but none of this row appears to be singing, as none has their mouth open – with the exception of the zither player on the far right, perhaps.

The equivalent, central row of angels on the right of the painting is similarly disposed. Two may be singing, most are praying, and three are instrumentalists. There is another long, silver trumpet – although most of this is hidden behind other angels. Nevertheless, a figure playing double pipes (also silver leaf) looks towards the trumpeter – who is wearing a helmet. It is possible that he represents one of the Powers, the fifth choir of angels, who are sometimes shown wearing armour. Just below the double-pipe player, a figure in blue holds what I take to be an angelic shawm. I say ‘angelic’, as shawms, which can be this shape (particularly if they are higher-pitched examples), tend to be made of wood, whereas this is clearly silver leaf, which I’m taking as being simply more heavenly. On the left of this choir is the only angel in the company that we can name.

In many ways he looks exactly like all the others – short, blonde, curly hair and an innocent face with a perfect complexion. These features remind us that the angels are in a state of grace – they have no taint of sin, and so are without mark or stain: they are immaculate. Like all the other angels (you can go back and check!) his halo is picked out with a black circular outline, and tooled with one circle just inside the black, and two more further in. In between these is a ring of small, circular marks each of which would have been made by tapping a small ring-shaped tool (basically a tiny tube) onto the burnished gold leaf, using a small hammer or mallet. His clothes and wings are all blue, but touched with gold, and while the feathers appear to continue across his clothing, if you look carefully at the gold trims at the shoulders, elbows, cuffs and skirt, you should be able to see that he is wearing blue armour – a different version of ‘heavenly’, perhaps. He also holds a silver shield and sword. This is St Michael, one of the archangels (the 8th choir, just higher in status than the ‘angels’ themselves), responsible for weighing the souls at the Last Judgement. He also defeated the dragon – “that old serpent, called the Devil and Satan” (Revelation 12:9) when some of the angels rebelled – and fell.

At the bottom left of the painting it is worthwhile noticing that relatively few of the figures are dressed in the deeper, richer tones – there are more light blues and pinks, a few yellows, and maybe as deep as a salmon pink and jade green – but this is partly to make a lighter, more ethereal contrast to the dark blue ‘ground’ which slopes up from the bottom left corner of the painting towards the right of this detail. On the right there are more trumpeters, and on the left, two viol players. Others sing, and even dance – there is a sense of movement from left to right, towards the centre of the image, and so towards Christ. All of the haloes are depicted in the same way as St Michael’s, although they overlap here more than anywhere else, telling us not only that the angels are several layers deep, but also that Fra Angelico already knew how to create imaginary space and depth on a two dimensional surface.

For whatever reason there is a greater preponderance of musical instruments at the bottom right: two more trumpets, a tabor, silver cymbals, two more shawms and two more viols (one of which is not being played). The angels on this side lean also lean towards the centre, and again they are layered several rows deep. They are also standing on the same sort of blue slope. On the far right, one of the angels appears to have turned away from us – but look how beautifully his wings are foreshortened, another indicator of Fra Angelico’s spatial awareness.

The blue base of the painting reaches a curved summit in the centre. It is the very top of a blue sphere, the vault of heaven, or, to put it another way, the sky. We are down on earth, in the middle of this, with the blue sky above and around us. Were we to penetrate this blue sphere – which surrounds us on every side – we would be in heaven. The medieval mindset saw the cosmos as being structured by a series of nine crystalline spheres, each of which was moved by one of the nine choirs of angels. Set in these were the sun, moon and five known planets (though not in that order), and the ‘fixed stars’. The blue of the sky – which we now know to be a result of the dispersal of sunlight – was seen as the last boundary between our ‘world’ and the golden light of heaven. The angels in this painting are therefore seen as dancing on the sky, or poised in the heavens above. In the centre of the painting here we see the full length of five silver trumpets, the cheeks of the angelic musicians puffed out as they look up towards Jesus – whose feet are just visible. Below him, two angels kneel playing portative organs, the one in pink again shown with the most brilliantly foreshortened wings, both of which come down on a slight diagonal. It is a beautifully conceived figure, I think, with the back of the head seen tilted subtly to the left, and a twist through the torso. The feet come back to our left, while the shoulders are facing more fully away from us. Even in this tiny detail the colour chords are superb – on the left, blue and gold wings with pale green robes lined with red, and a yellow underskirt. On the right the subtly modulated pink robe is lined with a violet blue, almost as if breathing in the sky beneath, and it is trimmed with the finest hem of gold.

Christ stands in the centre, made prominent not only by the golden radiance surrounding him, but also the white of his robes and flesh, as well as the brilliant red of the crosses on his flag and halo. The gold is incised regularly with lines which – as the word ‘radiance’ suggests – radiate from behind him, reaching slightly different distances into the burnished gold background. They would have been made using a ruler as a guide, and a stylus gently applied to indent the thin gold leaf without cutting through it. As candles flickered in front of this, the central panel of the predella, the glow around Jesus would have been modulated, reflecting the flickering of the candles, while the white of his robes would have maintained a more steady brightness. His right hand is raised in blessing, and shows the wound from one of the nails which held him to the cross. The wound in his chest, caused by a spear, is also visible. This is after the resurrection – indeed, it could be the resurrection itself. His white robe is effectively the shroud in which he was buried, now used as a form of toga, and the pallor of his skin reminds us that he was dead. He stands, as he does sometimes in the resurrection, on wispy white clouds. They are almost invisible now, as they were painted on top of the gold, in between the silver leaf of the trumpets, and much of the paint has worn away: it doesn’t adhere well to gold leaf. His halo is picked out, like those of the angels, with concentric circles, but there is more texturing: groups of four rings arranged in diamonds, and additional indents in the form of dots. His subtly rosy cheeks hint at his new life, and pick up on the red of the cross in his halo. And then there is the flag.

This is the flag of Christ Triumphant. It shows the red of his blood, and of his suffering, in the shape of the cross, the instrument of torture on which he was executed. The red stands out against the white of his purity and innocence. This is the flag he carries to mark his victory over death, and over sin, and he carries it, as often as not, at the resurrection. As a soldier fighting for good, and for God, it was adopted as a sign for St George, a figure shrouded in myth – but, as the first churches dedicated to him appear to date from the 4th century, it seems he was a very early Christian martyr. The dragon, of course, is just a symbol… His precise ‘nationality’ is by no means clear, but the most common belief is that he was from Cappadocia, in Turkey. As soldiers fighting for Christ – theoretically, at least – St George and his flag were adopted by the Crusaders, and finally, at some point in the late 1340s, he became one of the patron saints of England – gradually eclipsing St Edmund and St Edward the Confessor. He may have been born in Turkey, although some people think he may have come from Palestine, Syria, or even Israel. Let’s face it, he was not ‘English’ – even if he is now. Indeed, he is arguably England’s most successful immigrant. So the ignorance of people who have perverted this flag with their racist and xenophobic views appals me. As Jesus himself said (Matthew 25:35-36),

35For I was an hungred, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in: 36Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me.

If you’re doubting the ignorance of these people we may have a problem on our hands. I would go further: it is stupidity. If they are using the flag to support the notion of ‘uniting the Kingdom’ then they have the wrong flag. It is the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (for the moment, at least), and, although England is a Kingdom, there is no United Kingdom of England. They should have the Union Flag – or at least a whole collection, including the saltire and dragon alongside the flag of Christ Triumphant.

Pardon the rant, but… But no, I stand by every word of it. However, on Monday I guarantee we will just look at the paintings, with not a word of politics. Well, that’s not true, of course. Art has always been about politics, and in this case there will be the politics of the Dominicans, and of Florence: the politics of the unelected Medici, for example. But that’s history, so it tends to be less divisive (with an emphasis on ‘tends to be’). The pictures are glorious, though – and we are free to make of them what we will. My aim is just to pick out the more relevant interpretations.

The lovely faces of the angels. A bit dubious about the flag, though.

Your blogs are always a highlight.

LikeLike

Dear Dr Stemp,

Just reading this most interesting overview of the Fra Angelico exhibition, after returning from a work trip.

I have friends in Florence who have also been entirely beguiled by the exhibition – and of course they’re lucky enough to be able to go several times.

I very much look forward to your two talks that I shall be able to attend.

Thank you also for your point towards the end regarding the flag of St George and the many vile ways in which too many people are trying to use it as a symbol of bigotry and worse, too often based on the most profound ignorance.

And yes, how right you are: politics and art are forever intertwined.

Janet GvK

LikeLiked by 1 person