I can’t believe it’s a year since I started this blog – more on that below, but if you want to celebrate this anniversary by reading, or re-reading (if you’ve been with me all that time) the first entry, it was Day 1 – The Rape of Europa. But for now, I want to concentrate on The Good Thief. Did you know he had a name? Both of them do, as it happens – Dismas and Gestas (for the Good and the Bad). The names come from the Gospel of Nicodemus, an apocryphal text which reached its ‘finished’ form at some point in the fourth century, although some elements may have an even earlier origin. The names recur in the 13th Century in the Golden Legend, although Jacobo da Voragine, the author, gives the Bad Thief’s name as Gesmas.

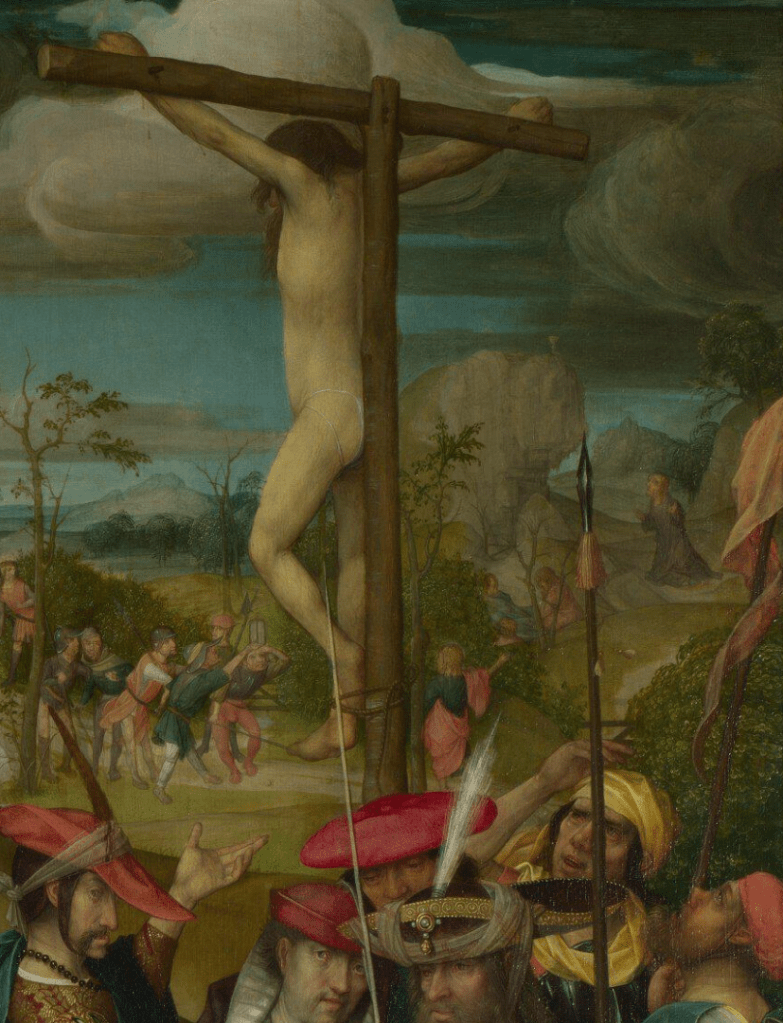

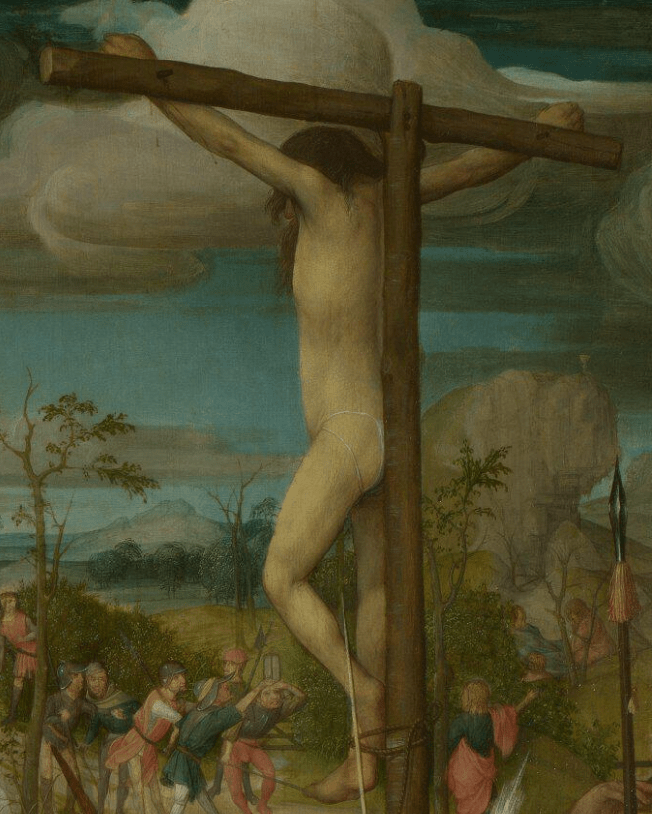

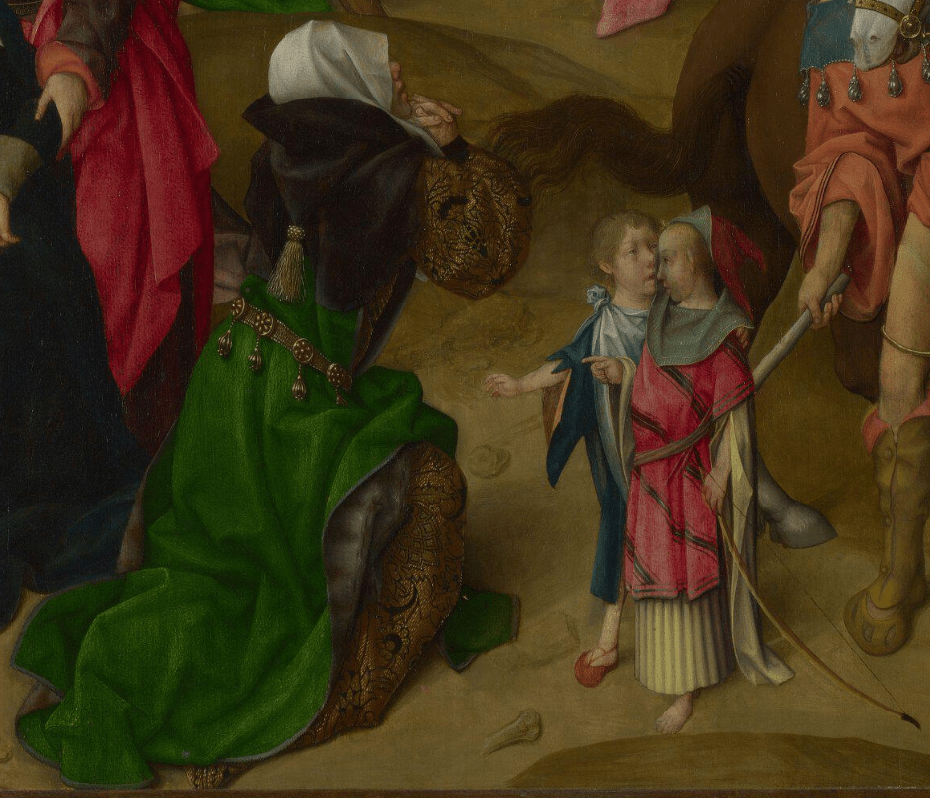

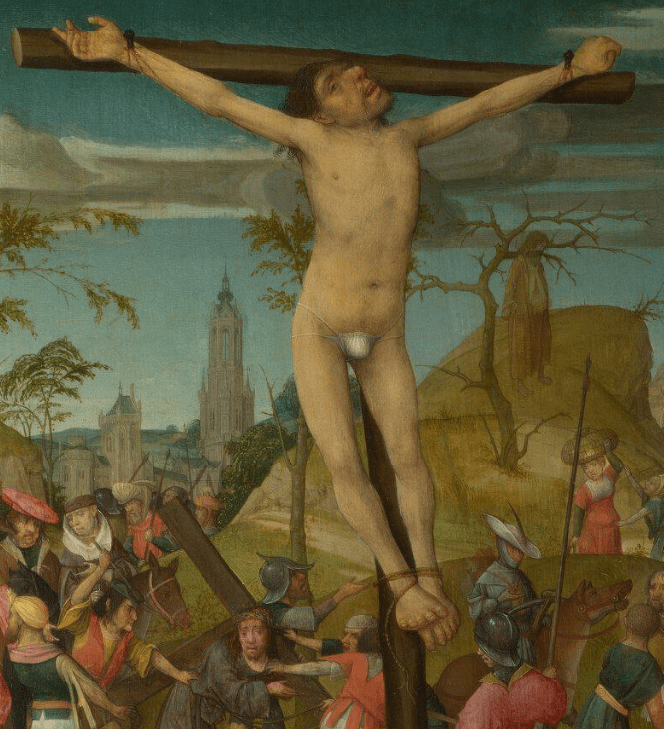

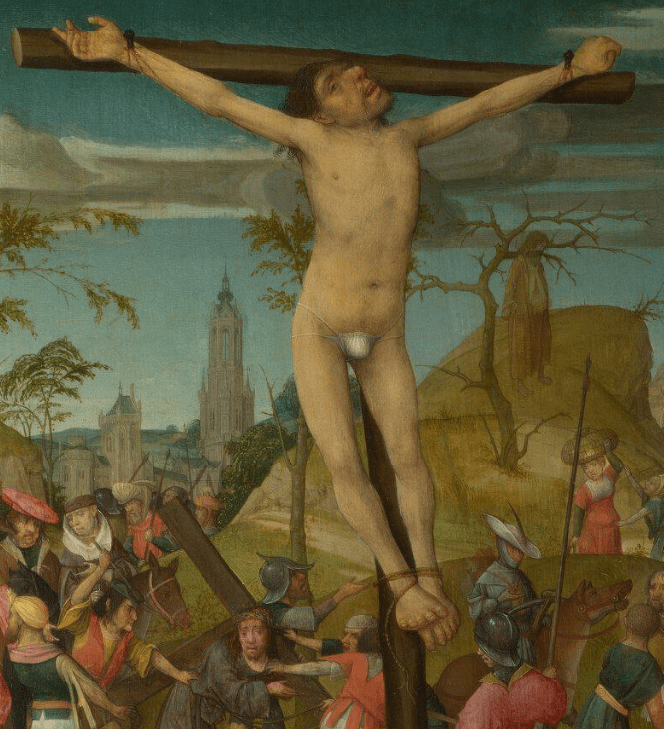

In the same way that I did yesterday, I’m going to ask, ‘How do I know’ that this is the Good Thief? Well, he is at Christ’s right hand (so, the side of the Blessed), and above the Good (the Virgin, John, and the Holy Women are just below him, although I have left no evidence of that in the detail I have picked out for today). He is also associated with Christ and with the Church: in the background we can see Jesus on the Via Crucis and the New Church in Delft. Although Dismas is contorted – a sign of his guilt, and of his repentance, perhaps – his back arches and his head tilts upwards – and so he faces heaven. He also has good weather… However, we can also see the post-suicidal Judas to the right. Maybe this implies that by taking his own life we know that Judas was repentant, and this, at least, could be considered ‘good’? I don’t know. As Hamlet says ‘the Everlasting… fix’d his cannon ’gainst self-slaughter,’ and surely two wrongs don’t make a right. But Judas must be there for a reason, and it is something along these lines. Maybe, at least, it is that ‘Justice’ is being done.

The text I quoted yesterday, in which Dismas admits that he and Gestas have done wrong, continues like this (Luke 23:42-43):

And he said unto Jesus, Lord, remember me when thou comest into thy kingdom. And Jesus said unto him, Verily I say unto thee, Today shalt thou be with me in paradise.

There is a problem here, as Jesus could not have seen him in paradise that day. To quote the Apostle’s Creed, he

…was crucified, dead, and buried.

He descended into Hell; the third day He rose again from the dead;

He ascended into Heaven…

It would be quite some time until he got to paradise. Maybe the problem is with the punctuation in the King James Version. Move the comma, and swap two words round, and it reads, ‘Verily I say unto thee Today, thou shalt be with me in paradise’ – which would work. However, I have just checked a parallel text website, and every single version (in English) implies that they would be in paradise that very same day. But then, as God, and the Heavenly Kingdom, are outside time, maybe that is actually possible.

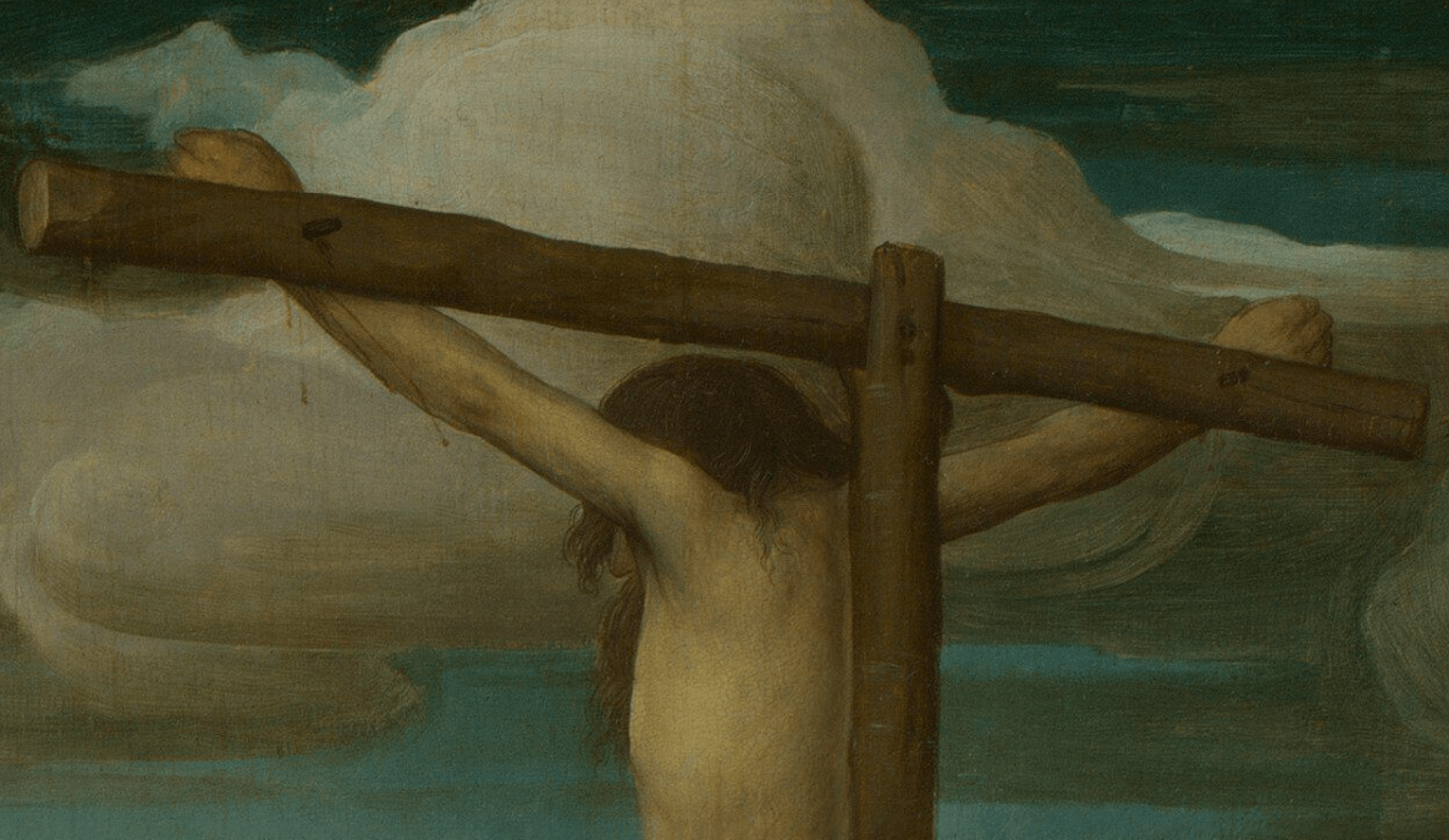

Like the Bad Thief, Dismas has the nails driven through his wrists, with his feet tied rather than nailed. This last detail is quite common. Both features probably derive from the will to make Jesus unique – no one else should be seen as dying in exactly the same way. That was why Peter chose to be crucified upside-down, according to church tradition (…but not the bible): he didn’t think himself worthy to die in the same way as Christ. Dismas, like Gestas, also wears a pouch with the thinnest of ties. Crucifixion was a humiliating form of execution – the very reason why the early Christians did not use it as a symbol for centuries – and for the thieves it is made even more humiliating, as a result of their degrading state of undress.

And another intriguing detail: the Good Thief has his right wrist nailed so that the palm of his hand is showing – like any other crucifixion – whereas his left hand is twisted round, so that the back of the hand is visible. I only noticed this yesterday. Maybe it is a frequent feature of Netherlandish art, but I have never seen it in any other painting. I will have to start looking. I can’t imagine what the reason for it might be. For now, I will just point out that it puts his hands into the same configuration that Christ’s adopt in so many images of the Last Judgement: raising with the right hand, and condemning with the left. This parallel with Jesus would certainly confirm his status as ‘Good’, but it seems to go a bit far… I must do some research!

The world has had a truly dreadful year, I know – but the last paragraph is an illustration of one thing that has been good about it, for me at least: I’ve learnt so much, given the time to look at paintings, to think about them, and then, to clarify my thoughts by writing. So thank you for giving me a reason to do this! And special thanks to those of you who have been along for the ride since Day 1. For those who haven’t, I started the ‘Picture of the Day’ on my Facebook page, and only migrated to this blog some weeks later. I had no idea where we were going – none of us did – but I wound down ‘Picture of the Day’ after 100 days just as we were coming out of lockdown, and museums were re-opening. Back then none of us knew (we really should have done) that we would go into lockdown again. And again. Once more, the signs are positive (I had my first jab this week!), and I am continuing to learn. So thank you all, for all of your support – first of all with this blog, and then with the latest thing I have ‘learnt’, which is how to work for myself! Which reminds me – it reminds me to remind you that my second series of talks, Michelangelo Matters, starts on Monday with The Development of David at 2pm and 6pm GMT – some details are on the diary page, and the links there will lead you through to Tixoom who deal with all the bookings, where there are longer descriptions of the three talks. I do hope some of you can join me. And after that – well, the third series has already been planned, but more about that another day. In the meantime, it’s still Lent. So – until tomorrow, enjoy the rest of your day!