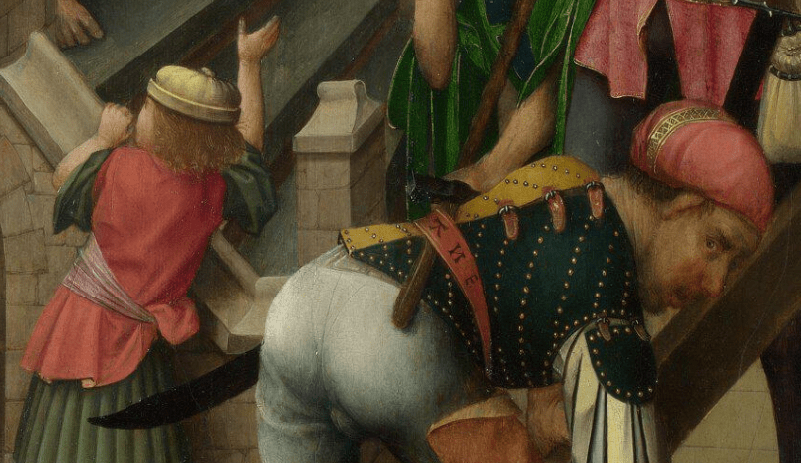

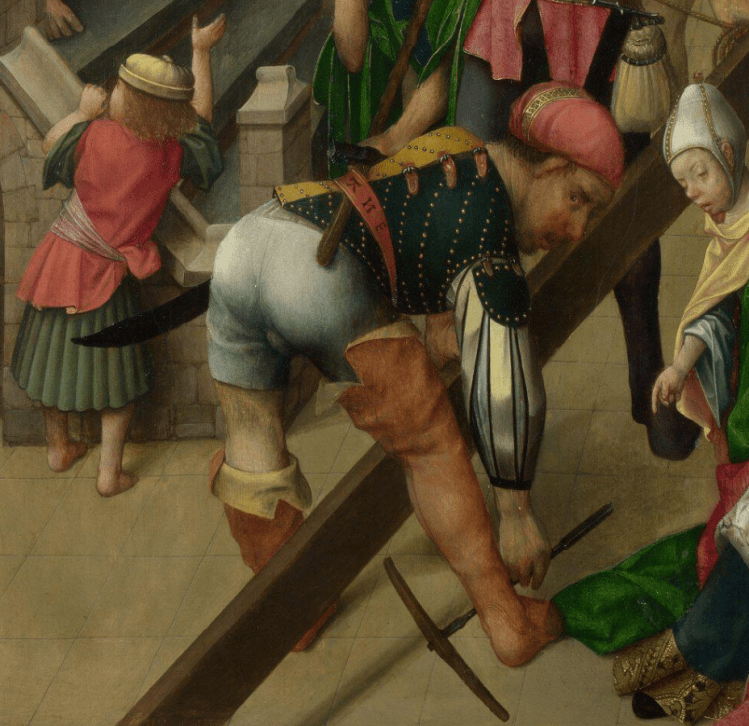

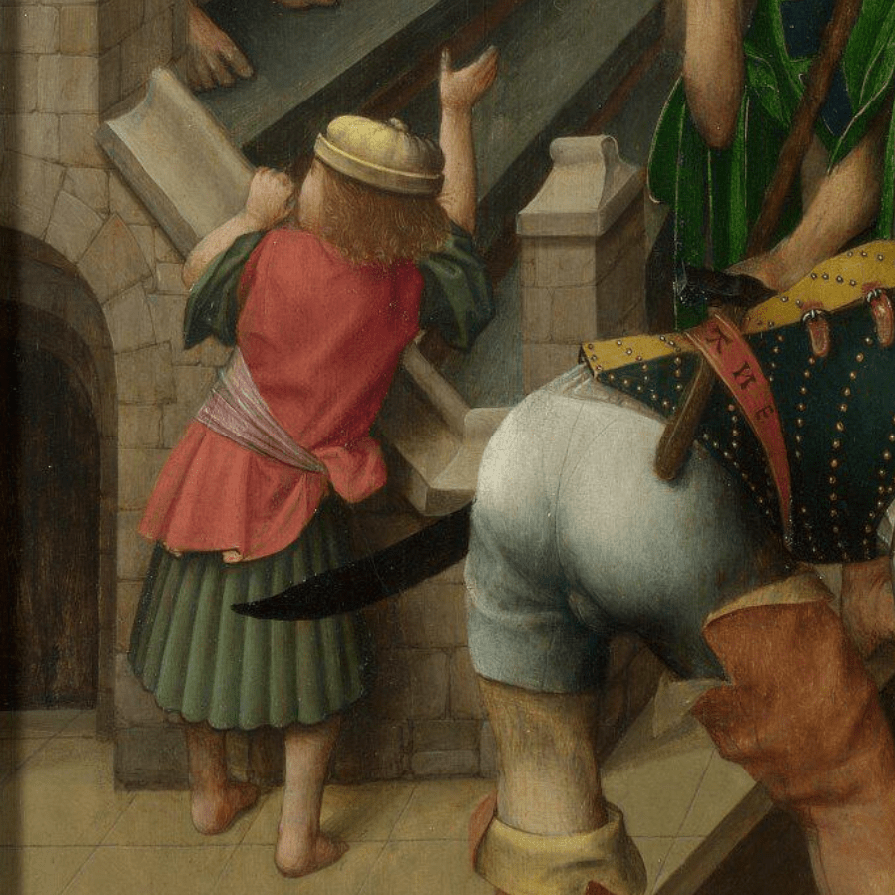

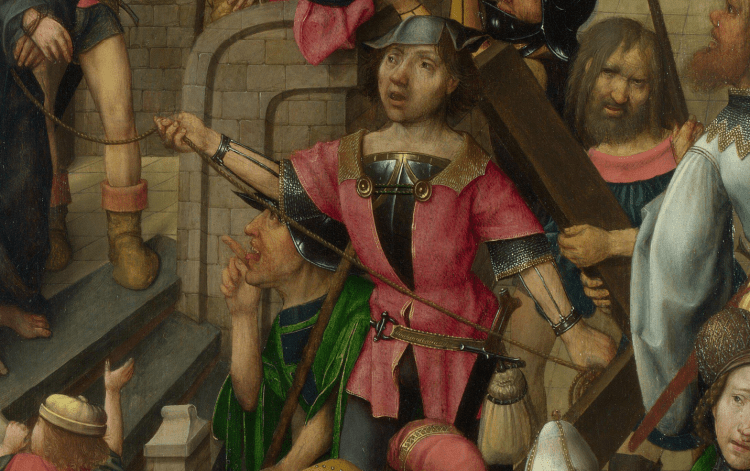

This is the Via Crucis – ‘The Way of the Cross’. So we know now, now it is confirmed (as if we didn’t know before) what the outcome will be. Jesus is carrying his own cross, with two guards, mainly out of view, pulling him on, and another behind grabbing the same grey-blue robe we have seen him in before and pushing him on, threatening to strike him with something blunt… I can’t see what it is but it doesn’t matter, it could easily be a wooden spoon, but whatever it is, it is being used as some form of goad. Another guard gestures ever onwards, his back to us, looking over his left shoulder, with a yellow headdress knotted at the front. Although I didn’t show it to you in full, this is the same type of headdress as the snub-nosed guard we saw in Lent 16, whose gesturing hand pointed the way in Lent 19 – that detail does at least show the knot at the front of his headdress – which was red. Nevertheless, I suspect this is supposed to be the same man – his chain mail collar changed to red fabric, the full sleeves now slashed. He’s a type, not a person though, so it doesn’t really matter if the assistants didn’t match the outfits from one appearance to the next.

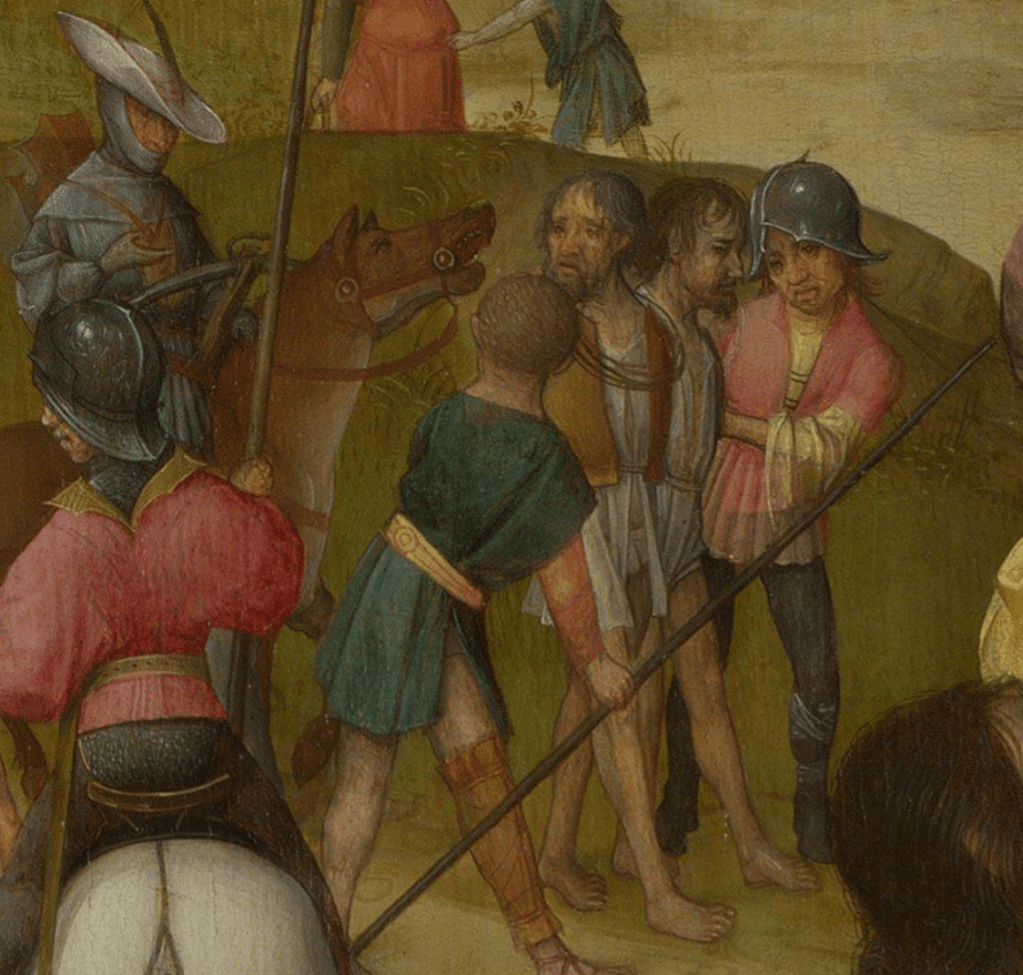

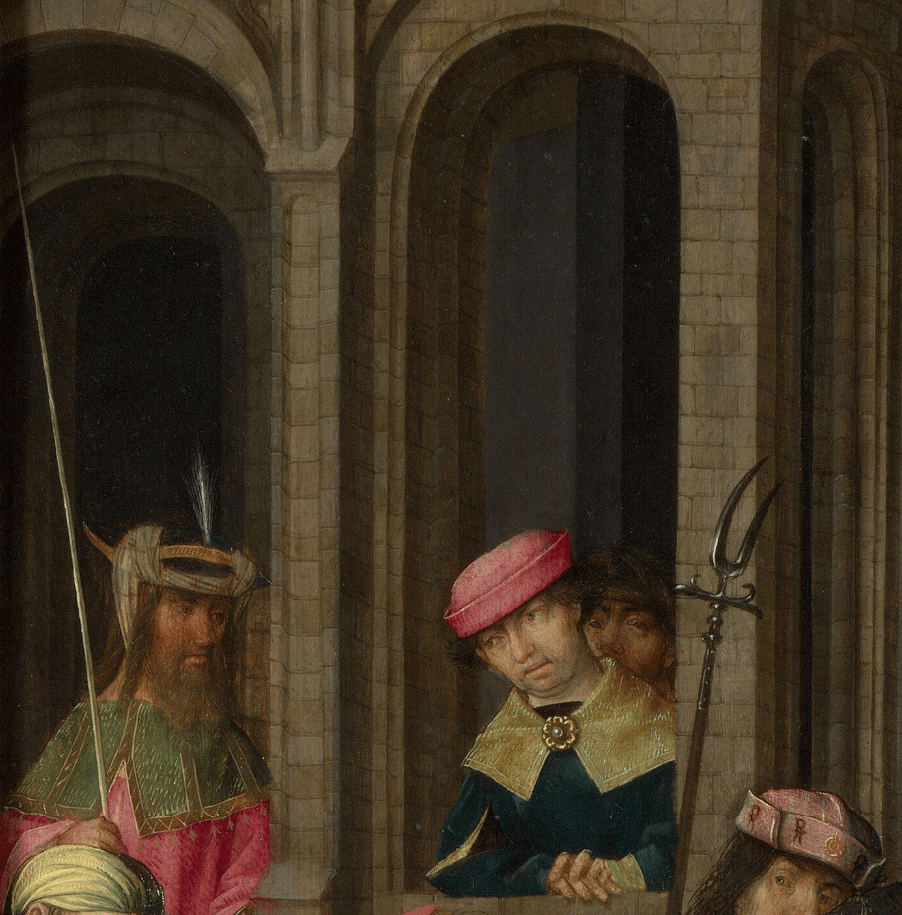

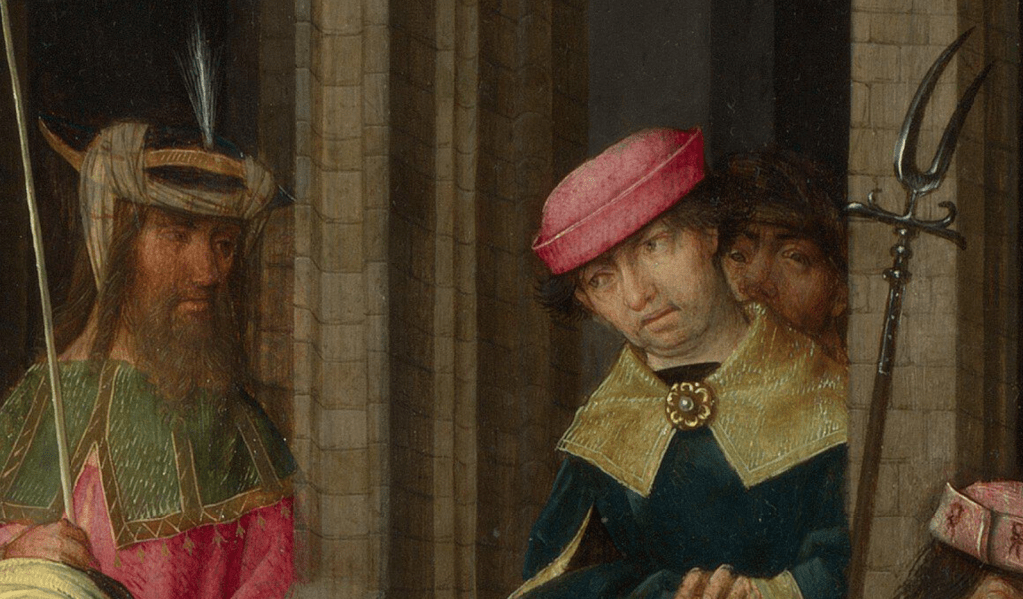

Following the condemned are the ‘great and the good’ of Jerusalem. Or, to put it another way, the guilty parties responsible for Christ’s imminent death. At least Pilate tried to have him released, according to John, but nevertheless, here he is at the front of the procession of presiding dignitaries. We last saw him standing outside his palace in the same outfit (Lent 14): the wide hat, bound with a scarf, a tall plume sticking up from its centre, the full-sleeved pink robe, with a green collar. It doesn’t look as green here – it is more like ochre, perhaps – and it doesn’t have the same detailing. But then, we are further away. He also holds his long, slim, staff of office in his right hand – with which he still manages to point – as well as gesturing with his left: ‘Keep him moving,’ perhaps. Behind him in the procession are two plump men elaborately dressed – one with a broad-brimmed red hat, another with something more like a purple pillbox, and a high, white, wrap-around collar. I suspect the latter was the man in the red hat, hands on the balcony, who we saw with Pilate at his Palace. Both of these men following Pilate must be chief priests.

The gospels say little about the Via Crucis – and the accounts we have, the tales which form the Stations of the Cross (which will have to wait for another day) – are not in the bible. No falling, no falling a second time, no Veronica wiping his face. The three synoptic gospels say that a man called Simon of Cyrene was pressed into service to follow Jesus and carry the cross, but there is no sign of him here. Luke also describes the attendant crowds, including the ‘Daughters of Jerusalem’ (Lent 18), as well as telling us that the two thieves were led away with him (Lent 19) – they are just a few steps in front. But John doesn’t mention this. He doesn’t mention Simon of Cyrene either, saying (19:17),

And he bearing his cross went forth…

So it is John who inspires this image. The T-shaped cross is lodged over his left shoulder, weighing him down, the length of it parallel to the angle of his back. Its left ‘arm’ is held in place by his left hand, which we can just see above the arm of the guard pulling him on, and supported by his right arm which reaches around in front. With the crown of thorns still embedded in his scalp, he turns his head towards us with a look of utter pathos. As one of the increasing number of the cast of characters aware of our gaze, he looks towards us and into our souls, evoking our sympathy, and reminding us that we are the reason for – we are the cause of – his suffering.