‘Myrrh’ –

Myrrh is mine; its bitter perfume Brings a life of gathering gloom; Sorrowing, sighing, Bleeding, dying, Sealed in the stone-cold tomb.

Once more John Henry Hopkins Jr. proves his knowledge of Origen. To complete the quotation that has built up over the last two days, ‘gold, as to a king; myrrh, as to one who was mortal; and incense, as to a God.’ (Origen of Alexandria, Contra Celsus, c. 248). So myrrh is a symbol for one who will die – it could hardly be otherwise, as one of its most common uses was in the process of embalming the dead. But Hopkins really rachets up the emotional key. I’ve always thought of We Three Kings as a stolid, but somehow jolly, Christmas carol – but this verse is entirely bleak, without the possibility, it would seem, of any respite from its ‘gathering gloom‘.

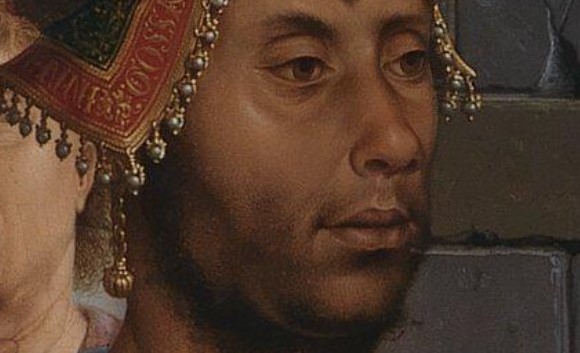

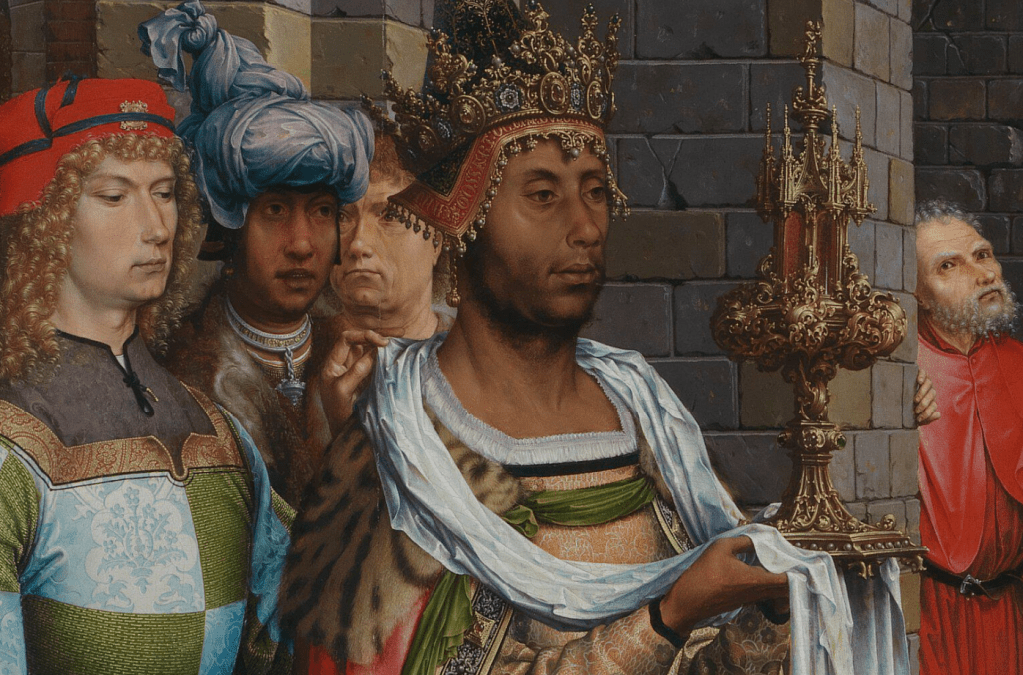

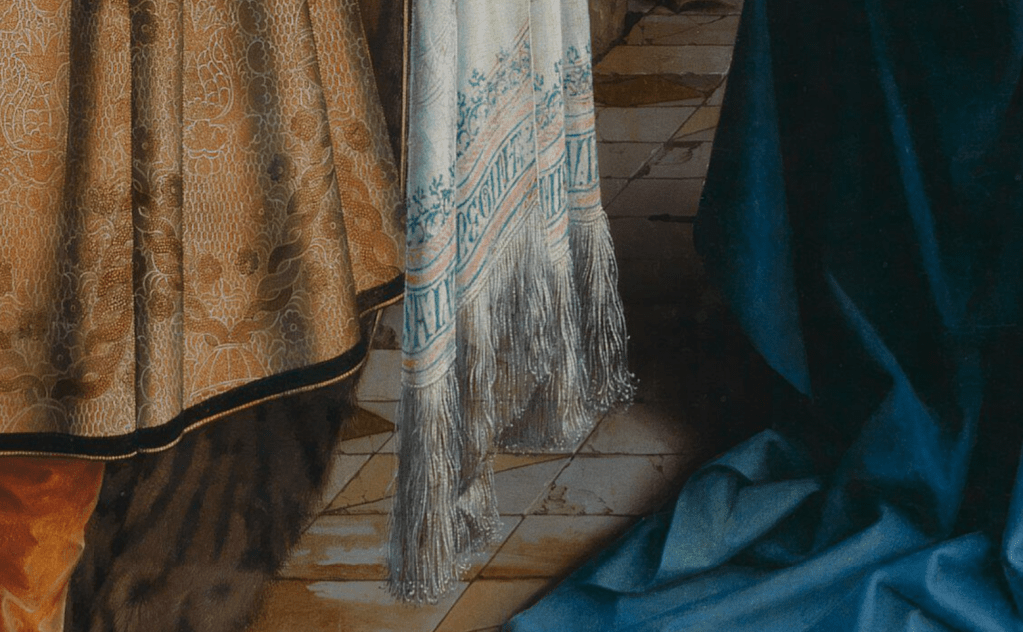

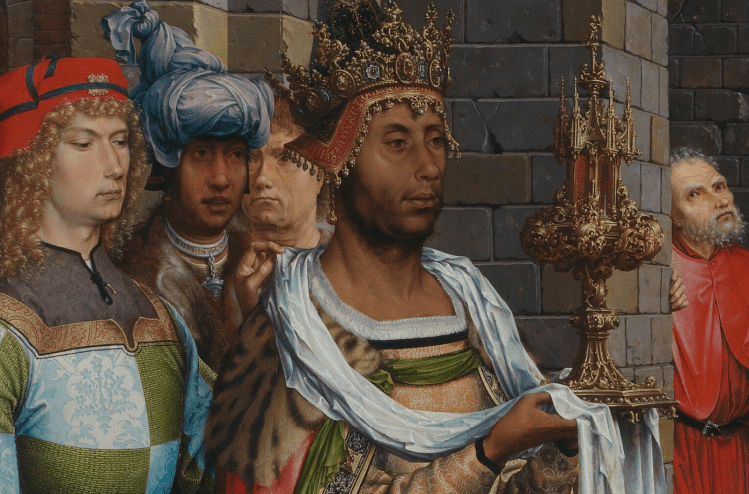

It is hardly surprising, then, that Balthasar should look entirely serious. Not only that, but he holds the gift with the reverence due to a ciborium, the name of the vessel used to preserve the consecrated host – in Catholic belief the actual body of Christ. Notice that he does not touch it, but holds it with the white, ceremonial stole around his shoulders, the one which his servant – or, at least, chief attendant – is adjusting. However, as it would traditionally be a priest that would wear such a stole, we must ask if Gossaert is suggesting that the Magi were, in some way, priests?

The ends of the stole are beautifully fringed, and also embroidered, bearing the inscription SALV[E]/ REGINA/ MIS[ERICORDIAE]/ V:IT[A DULCEDO ET SPES NOSTRA] (‘Hail, Queen of Mercy, our life, our sweetness and our hope’). The missing letters and words can be filled in as these are the opening lines of the 11th Century antiphon Salve Regina Misericordia, traditionally attributed to Hermann of Reichenau, although most scholars now doubt this (the link will take you to a YouTube recording, illustrated with a lovely detail from a painting by Signorelli – apologies again for any ads). This detail also shows us the remarkable diligence with which Gossaert painted Balthazar’s cloth of gold brocade, and the lynx fur which lines his cloak.

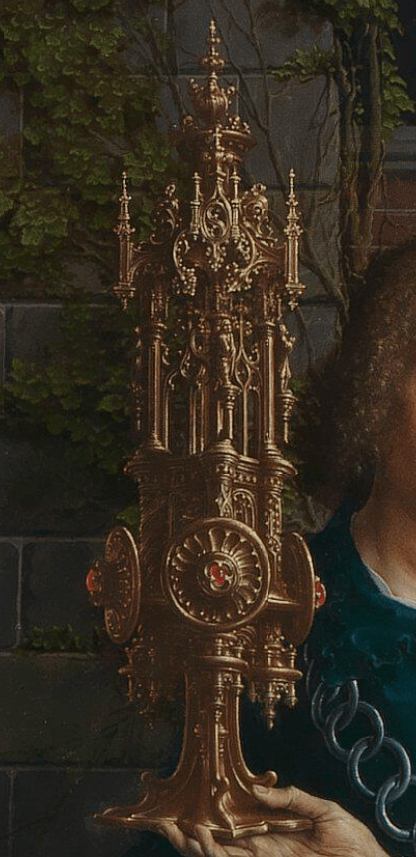

Yesterday I said Melchior’s container for the frankincense was like a reliquary – and then, perversely, illustrated the idea with a monstrance, an object designed to exhibit not a relic, but the consecrated host. I should really have said ‘monstrance’ in the first place, it would have been a better comparison, not just in appearance, but in function. If ‘incense owns a Deity nigh’, then what better way to show a deity, than with a monstrance? The wonderfully wrought vessel which Balthazar holds is every bit as impressive.

Once more it is made from gold, and, despite being held with two hands, it still appears to be suspiciously light – but then, any stress or strain in Balthazar’s hands would take away from the solemnity of the moment. As well as gold, at least one other material is used, and, in the same way that Casper’s gift was contained in a vessel with visual imagery, there are figures here too.

On the left, you can see the very top of Balthazar’s gift, with a miniature column flanked by two seated children. On top of the column there is a third figure, on his feet, stepping forward, and offering a gift. It is entirely self-reflexive: this object was made as a gift to be given. The detail on the right shows the central section. The red elements are part of the lid of the vessel. Just below them, behind the elaborate scrolling leaves, you can see a dark line which rings the object: it marks the join between the cup and its lid, which is ‘disguised’ by the stylised leaves. The gold is inset with a number of cut stones, polished to a shine, and the highlights suggest that they are carved into a series of niches under the gold gothic canopies. The mottled lighter and darker reds make me think that they are supposed to be porphyry, a substance associated with both royalty and death: the Byzantine emperors were buried in porphyry tombs, the name being equivalent to purple, the colour of their robes. So this is another reminder of Christ’s status as King, and of his destiny: to die on our behalf.

So, Myrrh – an omen of death – in a vessel decorated with porphyry – associated with death. There is no getting away from this – the Boy Born to be King was also born to die. We have seen this already. The image of The Sacrifice of Isaac carved on the capital atop the shiny red column is the image of an Old Testament patriarch prepared to sacrifice his only son, a foretelling, in the Christian context, of God the Father prepared to sacrifice his only son. The column itself would undoubtedly have reminded the devout of the column to which Jesus was tied for the flagellation. It is, bizarrely to our modern-day sensibilities, precisely this preparation for suffering and death that Christmas is all about. You can see it in the material values of the painting itself.

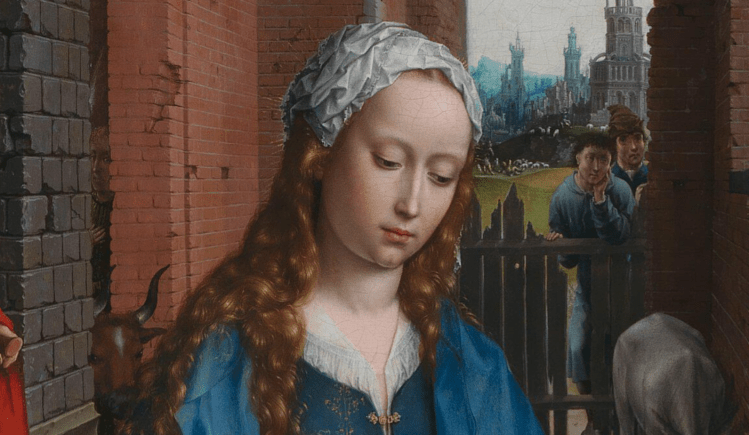

If not in the very background, then at least at the back of the foreground section, we can see the shepherds leaning on a wooden fence, the slats broken, or missing, a knot hole visible to emphasize its material nature. The wooden fence closes off a gap in the brick walls, the bricks being down to earth (like the shepherds) as they are little more than baked clay. Closer to us Joseph emerges from a gap in the stone walls: stone is more valuable, and potentially more enduring. It is solid, and reliable, just like Joseph. And if we keep moving forward we get to the gold – here it contains myrrh, elsewhere gold, elsewhere frankincense. All pretty valuable, all fit for a king, someone both god and man, eternal, yet born to die. And closer still – closer than the gold? What is the most valuable thing? From wood to brick, brick to stone, stone to gold – well, the most valuable thing would be Jesus himself. Now there’s a gift. He is embodied in the gift of gold, as the coins are just like wafers, the consecrated host, the body of Christ, gathered in the ciborium-like cup, ready to distribute to the faithful in front of the altar, in front of this painting.

And the carol? Well, the author was a rector, remember, he knew what he was talking about. Balthazar’s verse is entirely without hope, it seems, but it is only the fourth verse of five. There is one to go, and one which draws together the preceding three – all three of the gifts, and their meanings. And it goes that one step further, because, curiously, this carol is not about Christmas, in the end. It is about Easter.

Glorious now behold Him arise, KING, and GOD, and SACRIFICE; Heaven sings Hallelujah: Hallelujah the earth replies.

And of these words, the most important is surely ‘arise’.