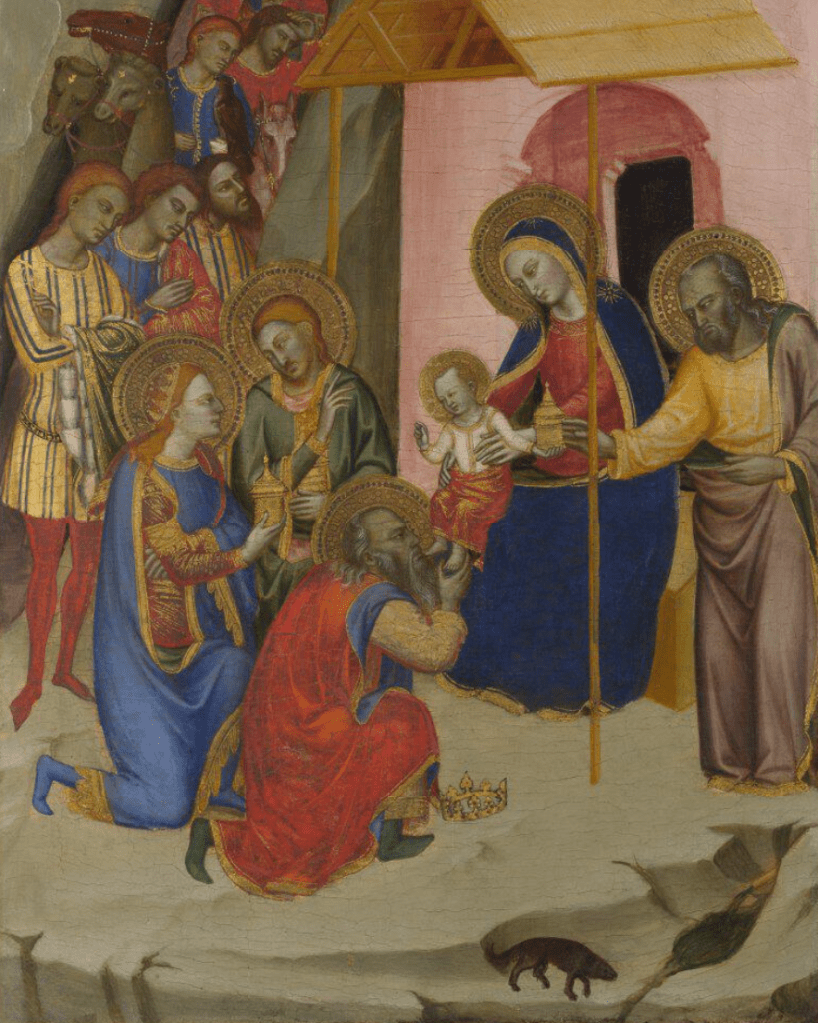

Jacopo di Cione and workshop, The Adoration of the Kings, 1370-71. The National Gallery, London.

I know, there are still 118 days to go before Christmas, but even so I have decided to look at a painting of the Three Wise Men. I’ve chosen this painting because the protagonists feature in Jacopo di Cione’s magisterial San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece, one of the National Gallery’s great unsung masterpieces, which will be the focus of my talk this Monday, 2 September at 6pm. Entitled Who’s Who in Heaven: 1. Around the Queen, it is the first of two talks dedicated to saints. The Queen in question is the Virgin Mary, the Queen of Heaven, and in the altarpiece she is surrounded by no fewer than 48. My intention had been to talk about all of them, but honestly, what was I thinking? Given that I would like to put them all into the context of early Italian painting, I clearly won’t be able to cover every one. The talk will serve as an introduction to this fantastic polyptych, and will also be a reminder of what sorts of things we should look for – and why – when we are identifying the people represented in Christian art. Two weeks later, on 16 September, I will follow up with 2. Behind the King, taking the jewel-like Wilton Diptych as my starting point. We will look at the religious and political concerns of King Richard II, and use what we have learnt to draw some conclusions about the the importance of context when interpreting other religious art.

At the end of the month, on 30 September, we will take a virtual journey around The Piero Trail, and finally (for now) on 14 October, I will be introducing the National Gallery’s main offering for it’s bicentenary, Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers. However, rather than the purple prose on the Gallery’s website, I would like to think about what the paintings themselves tell us, hoping that this will be Vincent, Speaking for himself… Details, as ever, are in the diary.

The San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece is a remarkable survival: a four-tiered polyptych painted in 1370-71 for the eponymous Benedictine church in Florence. Its survival is remarkable for a number of reasons, the main one being that the church itself was destroyed in 1784. Even before that, the polyptych had been taken down from the high altar, and broken up because it was too large for the side chapel to which it was moved: the panels survive, but not the frame. The National Gallery has the three upper tiers of the polyptych. The predella, which originally formed the lowest tier, is elsewhere. Today we are looking at one of the panels from what would have been the third tier up, dedicated to a very abbreviated life of Christ, in six episodes. This the second of the six, The Adoration of the Kings. Having seen the star in the east, they have travelled to pay homage to the Boy Born to be King, and are gathered around him in the bottom half of the panel. He sits on the lap of his mother Mary, who stands out by virtue of her rich, deep blue cloak. This uses the highest grade of ultramarine, which would have been far more expensive than the gold leaf used for the sky.

The use of gold leaf was not profligate: it was beaten into such thin sheets that it was translucent – you could see light through it. If it had been stuck directly on to the white ground used for the rest of the painting, the white would have been visible through the gold, making it look rather dull. To avoid this, any area to be gilded would be prepared with a red, clay-based paint called bole, which, when seen ‘through’ the gold, made it look far richer – and far more ‘gold’. The bole can be seen around the gold at the top of the painting: they only gilded the section of the sky which would be visible once the panel was framed, for economic reasons. The shapes taken up by the gold and the painted hills on either side tell us the shape of the original frame.

There is a light brown hill on the left topped by a pale pink castle, with four trees growing further down the slope. On the right there is a taller grey-pink hill, with two trees growing as far up as we can see. There are two clefts coming down, one through the taller hill, and another between the brown and pink hills. From this cleft emerges the head of a horse, and below that we can see two camels, and several men. The entourages of the three kings are arriving from the valleys between the hills, which, in the painting, have been stylised into apparently impassable clefts: the painting is about storytelling rather than the depiction of naturalistic space. A thatched roof projects from a pink building on the right, and at its apex we can see a star – the star – which is precisely what has led the kings to this location. The thatched roof is part of the stable, which, as I’m sure you all know by now, is not actually mentioned in the bible.

Three men stand on the left, all fashionably dressed (for the 1370s, but not for the date of Christ’s birth), with the one we can see full-length wearing a short, striped, yellow tunic over the must-have item for well-to-do men: red hose. They are presumably the kings’ valets, or equivalent. The three kings kneel with different degrees of obeisance, the eldest bending the lowest. He has removed his crown and placed it on the ground in front of him as a sign of his humility, and he leans forward to kiss the child’s foot. Jesus hands the gift of gold to his stepfather Joseph, who is standing on the right of the picture. Below him is a gully, in which a pipe gushes water. It’s an odd detail which I’ve never seen mentioned anywhere, but I presume it is a reference to the coming of the Messiah, the Water of Life.

If we look closer at this scene, we can see how sophisticated the conception of the painting was, if not, maybe, the execution: this is why it is assumed that Jacope di Cione was assisted by his workshop. Well, that, and the fact that this was one of the largest altarpieces in Florence at the time, which would have required the collaboration of a numerous people anyway – carpenters, frame makers, assistants to mix the paints, goldsmiths to do the gilding, etc., etc. Delicately poised on his mother’s knee, the Christ Child lifts his right hand in blessing, while his supernaturally strong left hand holds the gift of gold at arm’s length. He reaches over Mary’s hand as he passes it to Joseph, who reaches behind the supporting strut of the thatched roof to take it. Joseph holds the hem of his cloak – lilac with an olive-green lining and gold trim – with his right hand. I’ve often imagined a whole pile of presents stacked behind the stable, but I probably shouldn’t be so frivolous. The folds of Jesus’s red cloak are picked out in gold, and the same fabric – red with gold highlights – is worn by the youngest king.

The age of the kings is clearly demarcated: the youngest has no facial hair and a pale complexion, a sure sign that he hasn’t been out in the world that long. He still wears his crown (knowing that he will be last in line to greet the infant) and holds his gift (myrrh) in his right hand, the left tucked under his right arm. Next to him, in green, the ‘middle’ king has a full head of hair (like his younger companion) but also a moustache and short beard of the same ginger. He gestures with his left hand, his elegant, slim fingers widely spaced, with the forefinger pointing up towards the star: he seems to be telling the youngster that they are definitely in the right place. He has already removed his crown – although it is not clear where he has put it. The eldest has white hair, with a receding hairline, and a long white beard. He holds the Child’s left foot delicately between thumb and forefinger. We will see a very similar gesture, and consider its implications, when we look at the Wilton Diptych in a couple of weeks’ time. Notice that there are six haloes. Obviously Jesus, Mary and Joseph are considered holy, but the three wise men also have the unmistakable signs of sanctity.

There are three main panels in the San Pier Maggiore altarpiece: the central one shows the Coronation of the Virgin, while the flanking panels each has a group of Adoring Saints – it is mainly these that I will be looking at on Monday. Above each panel is a pair of narrative images, and the two illustrated here sit above the left-hand group of Adoring Saints. The one on the left shows The Nativity, with the Annunciation to the Shepherds and the Adoration of the Shepherds. Mary sits in prayer, under the same thatched roof, in front of the same building, next to the new born infant, who is swaddled and lying in the manger. The Ox and the Ass are lying behind the manger, in adoration, just like the two shepherds to the left. Above the holy mother and child, a choir of angels sings and plays heavenly music. St Joseph, in the same clothes as in the other panel, sits at the bottom left of the image. What should be clear is that both events – The Nativity and The Adoration of the Kings – happen in the same place. It is easier to see that if we compare details, though.

We have the same two hills, topped by a castle and four trees on the left, and two trees on the right, but the colours are different. The hill on the left is far darker in the Nativity than it is in the Adoration, but that is because the former takes place at night time. It is actually one of the earliest nocturnal scenes in a panel painting, the darkness emphasised by the glow of divine light emanating from the angel who is announcing the good tidings of great joy to the shepherds. The supernatural light gives the hillside with its two trees, as well as two shepherds, four sheep and a rather forlorn looking dog, a warm yellow glow. All of these things have gone by the time the Magi arrive, leaving the star to hold its own in the daylight. One of the features that has always amused me is that the stable has a retractable roof. Like a skilled theatre designer, Cione must have realised that there wouldn’t be so much space on stage with three kings and their retinues, so he pushes the thatched roof out of the way.

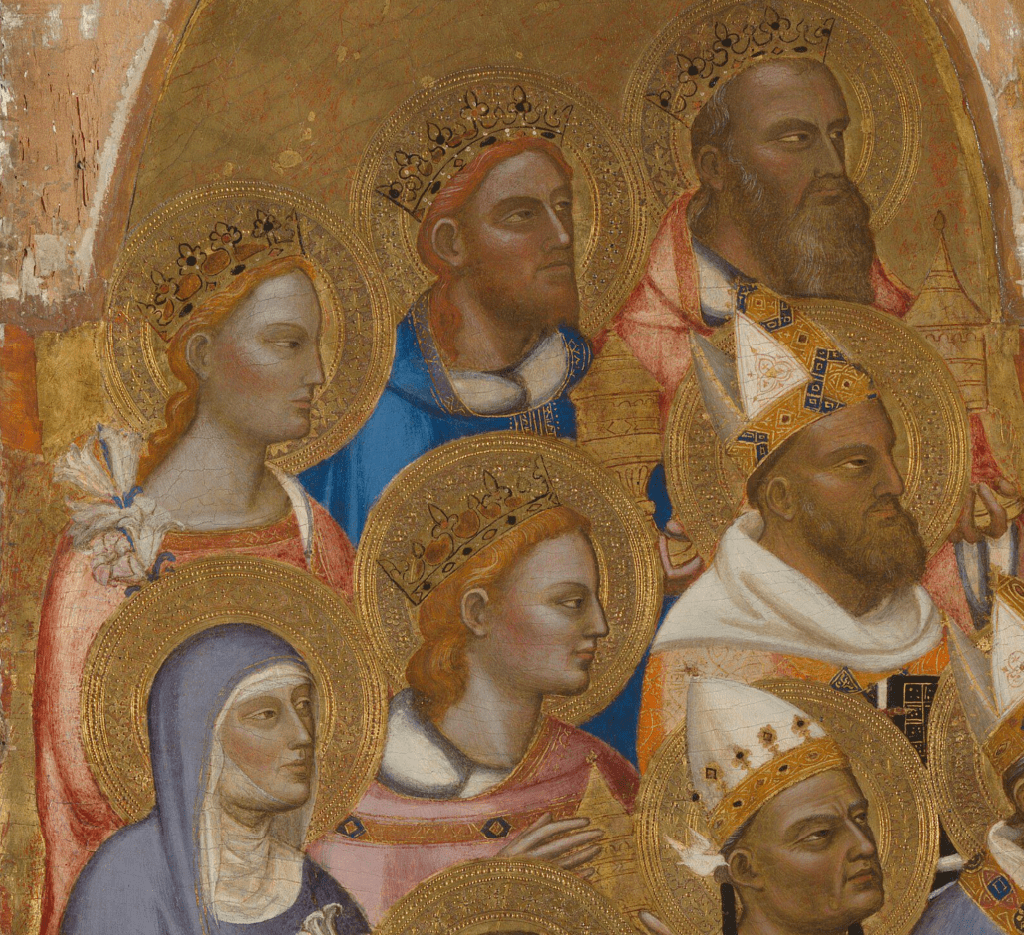

Aside from the shifting roof, the stable looks pretty much the same, and the stage is indeed far more crowded. In the foreground the rocky ledge on which the stable has been constructed has exactly the same cracks and crevices in both paintings, and both have the same gully with the pipe spouting the same flow of water. However, by the time we get to Epiphany (6 January) a creature has arrived to drink. I’ve always assumed it is a beaver. I have never known what it is doing there, nor have I ever seen a reference to it. The same shepherds which were atop the hill, watching over their flocks by night, are now at the bottom of the valley in prayer, one, with red hair, with his hands pressed together, and another, with a medieval hoodie, crossing his hands over his chest – another early form of prayer. They do not have haloes. How come they are not considered holy, but the Magi are? Is there a class bias? Are the poor labourers not considered worthy? It could, potentially, be worse. As the shepherds were in the nearby fields they were seen as locals, whereas the kings were clearly outsiders. As such, the shepherds came to represent the Jews who converted to Christianity, while the kings represented the Gentiles. Is it antisemitism that has denied the shepherds their haloes? I doubt it: no one has doubted the sanctity of the apostles… I have never heard of any relics of the shepherds, though. The kings, on the other hand, have ended up in Cologne – having been stolen from Milan by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I ‘Barbarossa’ in 1164 (they had been taken to Constantinople by the Empress Helena, where they were given as a gift – by her son, Constantine the Great – to the Bishop of Milan, in case you were wondering). They were highly revered in Florence, as it happens. This is a detail from the left panel of Adoring Saints.

It is a little confusing, as you can probably pick out four crowns. The one at the top left is a princess, though, a virgin martyr, presumably (she is carrying a lily), but I’m not sure if anyone has worked out which one. At the top right is the oldest king – usually given the name Caspar – with his receding hairline and long white beard, his gift of gold held proudly in front of him. At the top centre is the middle king (Balthasar, although the order of names was not fixed), with red hair, moustache and beard, also holding his gift. Directly below him, with his pale, beardless face, is the youngest, Melchior. Their appearance in the San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece reminds us that they were – and are – considered Saints by the Catholic Church (there was no other church in Western Europe at the time), but also that they were highly revered in Florence in particular. A religious confraternity, the Compagnia de’ Magi, was set up in their honour, and in the century after Cione painted his masterpiece many of the Medici family were members. Based at San Marco – the rebuilding of which was largely financed by Cosimo ‘il Vecchio’ de’ Medici – annual processions on the Feast of the Epiphany would pass along what is now the Via Cavour to get to the church. This is probably one of the reasons why the Medici built their ‘new’ palace in its prominent location on that street in the 1440s. It is also the reason why the chapel of the palace is decorated with Benozzo Gozzoli’s stunning Procession of the Magi, which winds its way around three of the four walls, with portraits of the Medici family included in the retinue behind the youngest king. Having said that, I would challenge anyone to pick out the three kings in the San Pier Maggiore altarpiece from a distance.

I’ve mentioned four of the Saints today – three kings and an anonymous princess (in the top left corner of the bottom left panel) – which only leaves 44 for Monday. Let’s see how many I can include…

#Sent from my iPad

LikeLike

Hi Anne – did you mean to post a comment? I can’t see anything! If not, don’t worry…

LikeLike

excellent Richard the talks you do are they recorded and accessible if not why not charge charge charge

LikeLike

Thank you, Craig – but no, the talks aren’t recorded. I prefer them to be more spontaneious, and it’s not always about the money, to be honest

LikeLike

I’m pretty sure your crowned female saint will be Ursula. She was a princess by birth, and although married , I think she persuaded her ‘husband’ not to consummate the marriage. Famously martyred with many companions ( estimates vary) .

Carpaccio tells the story in detail, of course.

Thank you for these explorations of art. Now that galleries are out of reach, I appreciate these virtual visits so much.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! You could well be right, although I would expect St Ursula to carry an arrow, or the Flag of Christ Triumphant… The woman in the Cione only has a lily, which suggests she was a virgin, but no palm of martyrdom – but then most of the saints in the altarpiece only have one attribute each.

My first impulse was that the cult of St Ursula was stronger in the Veneto, with the Carpaccio and Tommaso da Moden cycles in Venice and Treviso respectively, and I had never heard a reference to her in Florence. However, on checking, I’ve seen that there was a convent dedicated to her on via Guelfa which they are planning to open as a museum next year. There appears to be a Della Robbia workshop relief above the door which shows her (I assume) with a palm of martyrdom, but no lily. However, there were literally dozens of virgin martyrs (there is a whole wikipedia list), and more than one was probably a princess or queen… Without a direct association with San Pier Maggiore we may never be able to tell for sure!

I’ll ask someone I know who has done a lot of work on this painting!

LikeLike

Thankyou, that is so interesting. We used to walk along Via S. Orsola on our way to the mercato when we stayed near s.Annuziata. I had no idea the convent was there, it must have been completely shuttered. The net informs me that it was founded in 1309, so it would have been well established by the time of the altarpiece, I think. Quite a substantial institution in its heyday , judging from the aerial view.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person