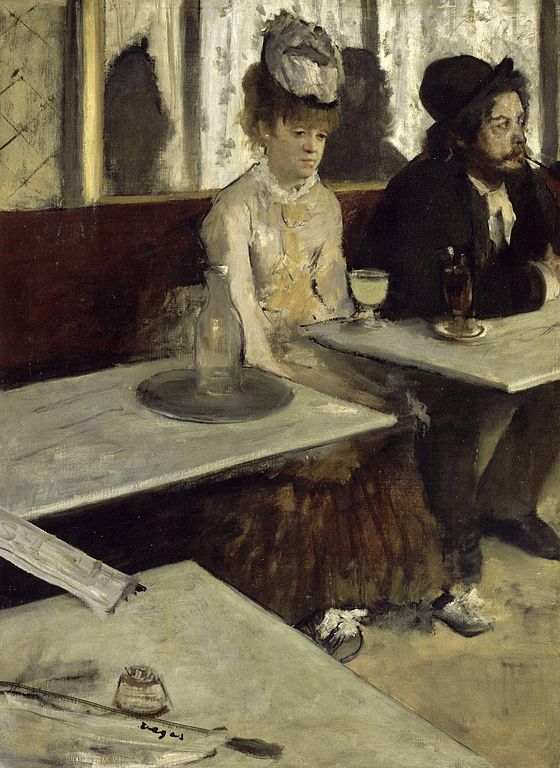

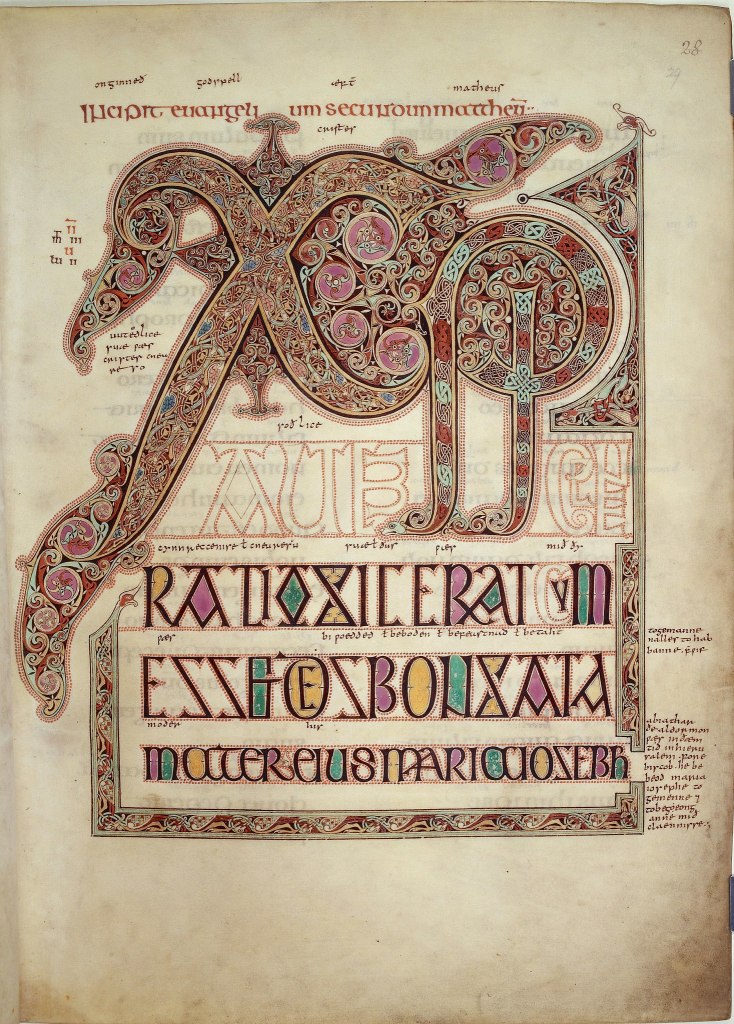

Salvador Dalí, Metamorphosis of Narcissus, 1937. Tate.

Salvador Dalí was a Surrealist, obviously, and, some would say, the Arch-Surrealist. In 1934 he even claimed a form of ‘über-Surrealism’ when he explained that ‘The difference between the Surrealists and me is that I am a Surrealist’ – a typically Surreal statement. As such, like all members of ‘Modernist’ movements, we would probably expect Dalí to turn his back on the art of the past and everything it stood for. However, on Monday I will be talking about one of his paintings of the Crucifixion, putting it (briefly) into the context of the rest of his career, and comparing it to a work by El Greco. Both are on show together at the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland in a display entitled Dalí/El Greco: Christ on the Cross – a micro-exhibition which is well worth a visit if you’re in the area before Sunday 4 December. Having discussed both works I will also introduce the Gallery itself (briefly) for those who haven’t been. I’m saying ‘briefly’ to myself as a reminder not to get carried away when I’m prepare the PowerPoint. Dalí, El Greco and the Spanish Gallery will be on Monday 14 November at 6pm, and if you can make it you’ll see whether or not I succeed! Other talks up until Christmas are, of course, in the diary, and there will be more news about my plans for the New Year soon. As I’m talking about Dalí and Christianity on Monday, today I thought I’d have a look at him confronting another pillar of Old Master Painting: classical mythology. So here is the Metamorphosis of Narcissus.

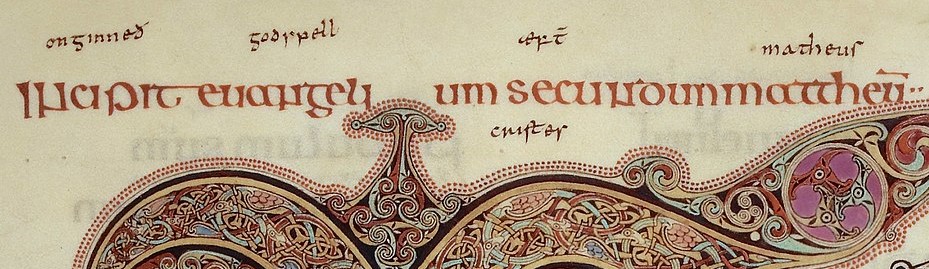

The story is probably well-known to you – or, if not the story itself, the general idea: Narcissus was in love with himself. Only that’s not exactly what happened. Let’s start by looking at the painting, though. There are two main forms set in a landscape. To the left of centre is a person crouching or sitting in the water at the edge of a lake. The right knee is strongly bent, and appears to lie across the surface of the water, where it is reflected in the mirror-like surface. This would only be possible if the figure was completely immobile, and had been still for some time: any movement and ripples would disrupt the reflection. The left knee is raised, and the chin of what must be the head (even if there are no facial features) rests on the knee. A chin resting on a hand implies thought – just think of Rodin – but here we can see that a knee can perform the same function: this figure is deep in contemplation. The shoulders are hunched, and frame the head, both being caught in the brilliant sunshine which streams down from the top left of the painting. The right arm is barely visible, bent back behind the form, with the hand probably resting, unseen, on the shore of the lake. The left hand is dipped into the water, though. We can see the articulation of the wrist, and the flare of the hand, but the fingers are out of sight. The arm frames the figure, and is bent at the elbow, with the joint itself in deep shadow. Like the right leg, the left leg and arm are both reflected in the lake. The hair, which seems to blend with the flesh of the forehead, is pulled back in a topknot, which blows in the breeze above the left shoulder. The head itself is furrowed and rough: to me it looks a bit like a walnut.

The ‘figure’ on the right is remarkably similar in form, but looks more like a sculpture, or statue, carved out of white marble. Standing on the shore of the lake, and a little closer than the human figure, it represents a hand holding an egg, delicately poised between the tips of thumb, index and middle fingers – it is a right hand. The ring and little fingers are both bent. A flower is growing from the egg.

If we take this detail out of context, the brilliance of Dalí’s conception becomes clear, if it wasn’t already. No longer are we distracted by the placement of the figures. It is irrelevant that the hand is closer to us than the human figure, as the head and the egg are at the same height, and appear to be the same size, on the picture surface at least (perspective would suggest that, as it is further away, the head is actually larger). However, now that we are looking closer we can see that the index finger does not touch the egg, but is at a small remove, the gap being equivalent to the area of shadow cast on the left shoulder by the head. In between the finger and the egg is a root – perhaps a development of the hair which has otherwise disappeared. Dalí is showing us metamorphosis – a change of form. However, in order to do so he is also using a staple technique of medieval and renaissance art: continuous narrative. This allows an artist to tell a story by showing the same character more than once in different time frames. Here we see Narcissus both before and after his transformation, or rather, perhaps, shortly after the metamorphosis has commenced, and when it is all but complete. But why does this happen in the first place? And how? The origins of the story are, of course, Greek, but it is told at its fullest in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a treasure trove of source material for classical myth which was used by artists across the centuries. Using these stories Ovid set out to show how everything changes: the world we live in is in a state of flux, and everything we know now was once something else. As such, it is a sort of origin myth, with explanations of the creation of many plants and animals, among other things, and story of Narcissus is just one of these – or maybe two, as his fate was tied in to that of Echo.

Long story short: Narcissus was so beautiful that everyone fell in love with him: men, women and minor deities alike. Beautiful on the outside, he was less than perfect within, and he treated all his suitors with bitter disdain. Eventually one of them begged the gods to let him know the same pangs of unrequited love that they endured, and the plea was answered by Nemesis, the goddess of retribution. This is how the story progresses, in a prose version I’ve just found on the internet (click on this link for the whole of Book 3, and if you start with line 339 you’ll get the story of Echo as well):

There was an unclouded fountain, with silver-bright water, which neither shepherds nor goats grazing the hills, nor other flocks, touched, that no animal or bird disturbed not even a branch falling from a tree. Grass was around it, fed by the moisture nearby, and a grove of trees that prevented the sun from warming the place. Here, the boy, tired by the heat and his enthusiasm for the chase, lies down, drawn to it by its look and by the fountain. While he desires to quench his thirst, a different thirst is created. While he drinks he is seized by the vision of his reflected form. He loves a bodiless dream. He thinks that a body, which is only a shadow. He is astonished by himself, and hangs there motionless, with a fixed expression, like a statue carved from Parian marble.

So he himself waits, motionless, like a marble statue – hence the stillness of Dalí’s figure, and the appearance of its equivalent, the hand. Important for the story, though, is that Narcissus did not know what – or who – he was looking at. As far as he was concerned it was a beautiful boy in the water, who actually reached out to touch and even kiss him – but who shied away at the moment of contact. Only later did he realise that it was his own reflection, and that his love was doomed, like that of those he rejected, never to be requited. In Ovid’s telling of the story, Narcissus weeps, and the tears disrupt the reflection, but still he continues to watch the effects of unrequited love on his own behaviour, and body:

‘As he sees all this reflected in the dissolving waves, he can bear it no longer, but as yellow wax melts in a light flame, as morning frost thaws in the sun, so he is weakened and melted by love, and worn away little by little by the hidden fire. He no longer retains his colour, the white mingled with red, no longer has life and strength…’

Eventually his sisters, the Naiads, lamenting his death, prepare a funeral pyre, ‘but there was no body. They came upon a flower, instead of his body, with white petals surrounding a yellow heart.’ So Narcissus is transformed into a flower: a narcissus, a type of daffodil. It’s Latin name is Narcissus poeticus – which is, of course, entirely apt – and this is what Dalí shows, with poetic (and surreal) ambiguity, emerging from an egg.

The lower half of the painting shows how ingeniously Dalí mapped one form onto another. The bent right leg becomes the ring finger, and its reflection is the little finger. The thumb is continued down to the wrist by its own reflection – and there is subtlety here: the surface of the water is mapped onto the hand with a crack in the marble. This gives the impression that the metamorphosis is ongoing, and that the stone will eventually break up and wear away. This feeling of decadence – literally a state of deterioration or decay – is enhanced by the ants which are swarming up from the ground and along the thumb. Ants are frequently included in Dalí’s art as symbols of death and decay, apparently the result of him seeing them on the bodies of decomposing animals when he was young. The scrawny dog has a lump of raw meat in its mouth. A scavenger, it might even be imagined as eating the flesh of the dead boy.

If we’re talking symbols, Dalí uses the egg as a sign of hope – of new life, or rebirth – hence its place as the origin of the flower. Like the rest of the hand further down the thumbnail is cracked – another sign that the transformation is continuing, and that eventually only the flower will survive. On either side of the hand are more elements of continuous narrative. The myriad figures to the left of the hand, stretching and writhing, are usually interpreted as Narcissus’s suitors, suffering the pangs of rejection, while to the right a figure stands on a plinth looking down: Narcissus admiring his own perfection. He’s been placed on a pedestal, either by the suitors, who have put him there metaphorically, or by himself: he has set himself apart, whether metaphorically or not. Placed on a grid like a chess board there is perhaps a sense of strategy at play here. And directly above this statuesque figure – a hint at what is to come – there is an echo of the finger tips holding the egg in a distant mountain. Maybe there are more people like Narcissus out there, suffering a similar fate.

Dalí did not always elucidate every detail of his work – probably just as well, given how much detail each painting contains – and as often as not he is providing poetic suggestions which give full rein to our own interpretative powers – and to our imagination. However, it is interesting to consider what his interest in this particular story was, and how it relates to his practice at the time. It is one of the fullest realisations of a technique he called the paranoiac-critical method. One of the main symptoms of paranoia is the ability to find links between things which, in reality, have no rational connection. Although not paranoid himself, Dalí had what was an extraordinarily active imagination, and, after letting himself go on more than usual flights of fantasy, he would re-form his ‘paranoid’ imaginings into a concrete image – the ‘critical’ side of the paranoiac-critical method. One of his suggestions about this particular painting was that you should stare at it in an unfocussed way until the two primary forms combine. A bit like ‘magic eye’ images – which rely on the left and right eyes focussing on two different elements of the image to allow the brain to resolve a single, three-dimensional design – he was basically suggesting that we let our focus go so that our left eye sees the left form and our right looks at that on the right. At that point the two forms would merge into one, and Narcissus’s transformation would be complete: the human figure would ‘disappear’ within the hand.

In 1938 the Catalan artist was taken to see one of his heroes, the Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud: both were in London. Dalí had read The Interpretation of Dreams years before, and Freud’s interest in the subconscious was one of the driving forces of his art – as it was for all Surrealists. On the visit he took this painting, Metamorphosis of Narcissus, with him, like a proud schoolboy eager to impress the teacher. Sources relating to Dalí tend to stress the positive outcome of this meeting, quoting Freud’s letter to Stefan Zweig, the Austrian author who had introduced the artist to the thinker, in which the psychoanalyst said:

I really have reason to thank you for the introduction which brought me yesterday’s visitors. For until then I was inclined to look upon the surrealists – who have apparently chosen me as their patron saint – as absolute (let us say 95 percent, like alcohol), cranks. That young Spaniard, however, with his candid and fanatical eyes, and his undeniable technical mastery, has made me reconsider my opinion.

Elsewhere, though, he said, ‘In classic paintings, I look for the unconscious – in a surrealist painting, for the conscious.’ Some suggest this was said directly to Dalí, thus completely undermining one of the cornerstones of the entire Surrealist movement. I shall leave you to look into Freud’s own theories about the story of Narcissus and its relationship to homosexuality for yourselves – the theory has long been discredited, even if this may well be the reason why Dalí chose this myth in the first place. For now, I am happy to enjoy the painting’s appearance. In any case, I would prefer to move on to Dalí’s interest in Christianity, which is precisely what I shall do on Monday.