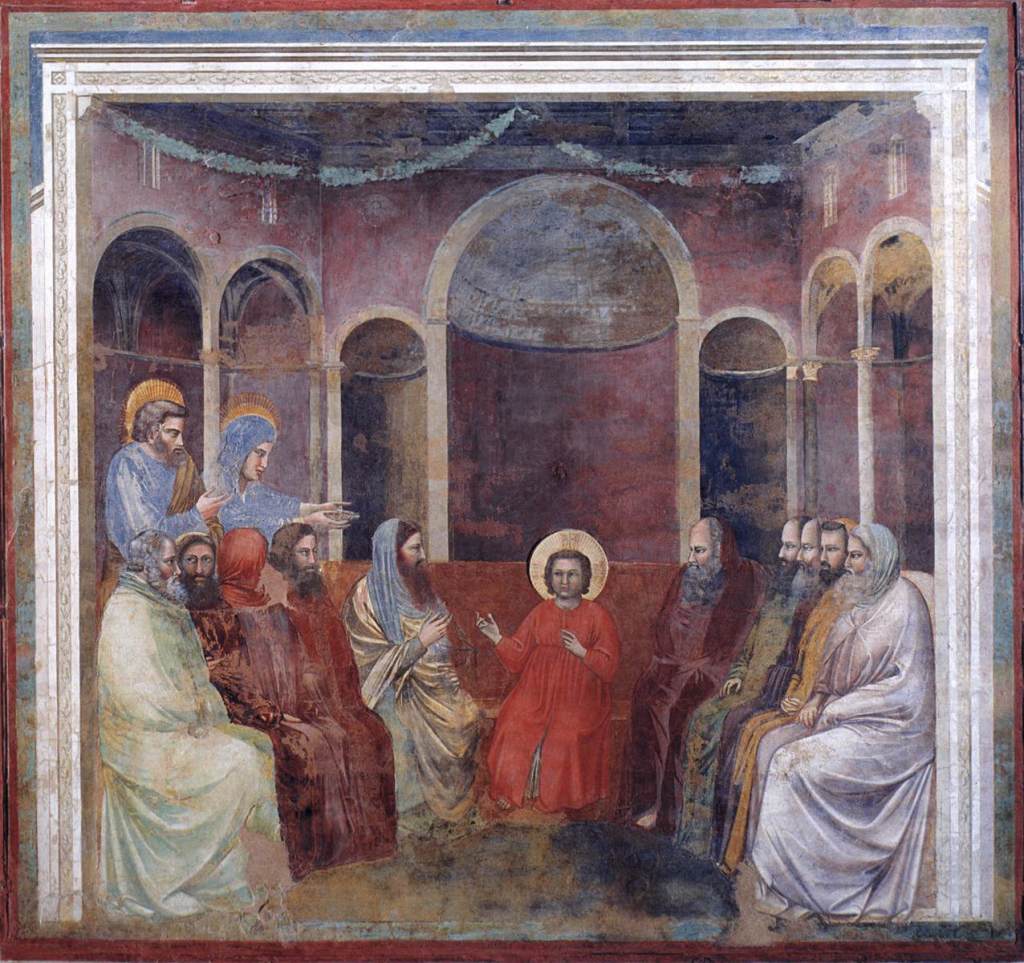

Giotto, Pentecost, c. 1305, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua.

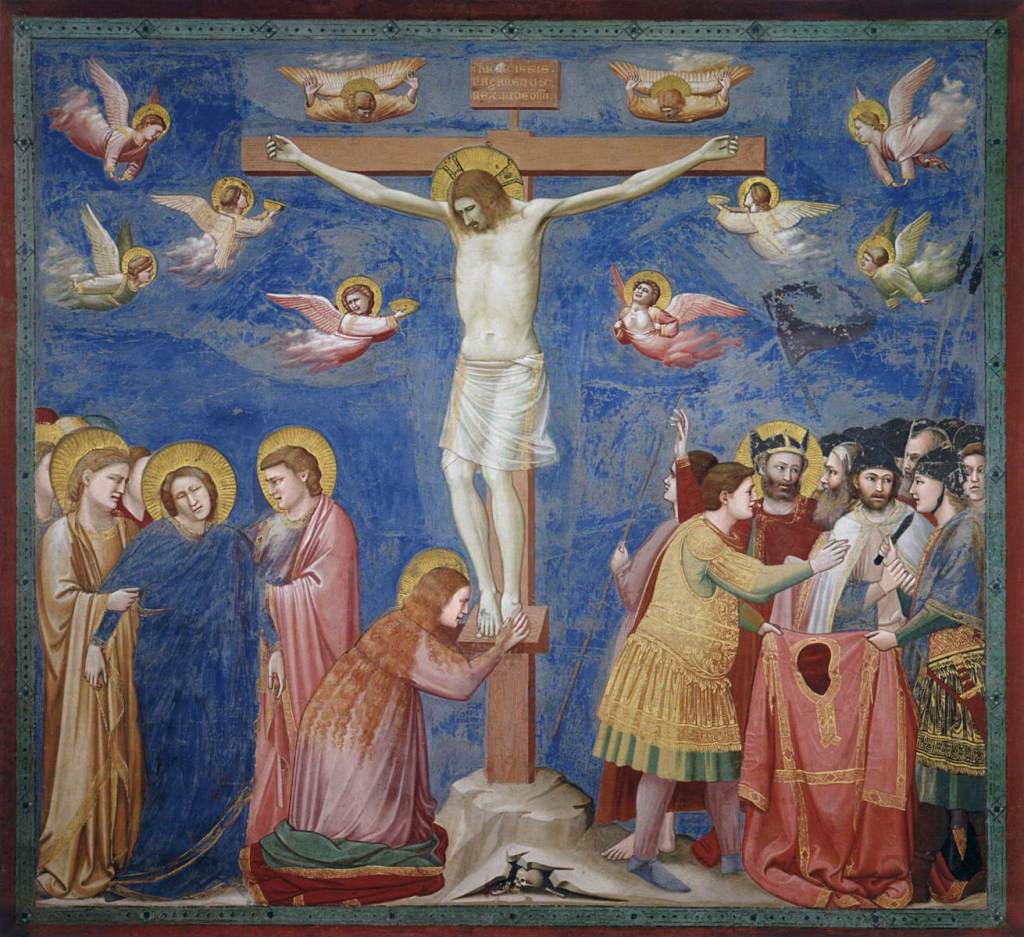

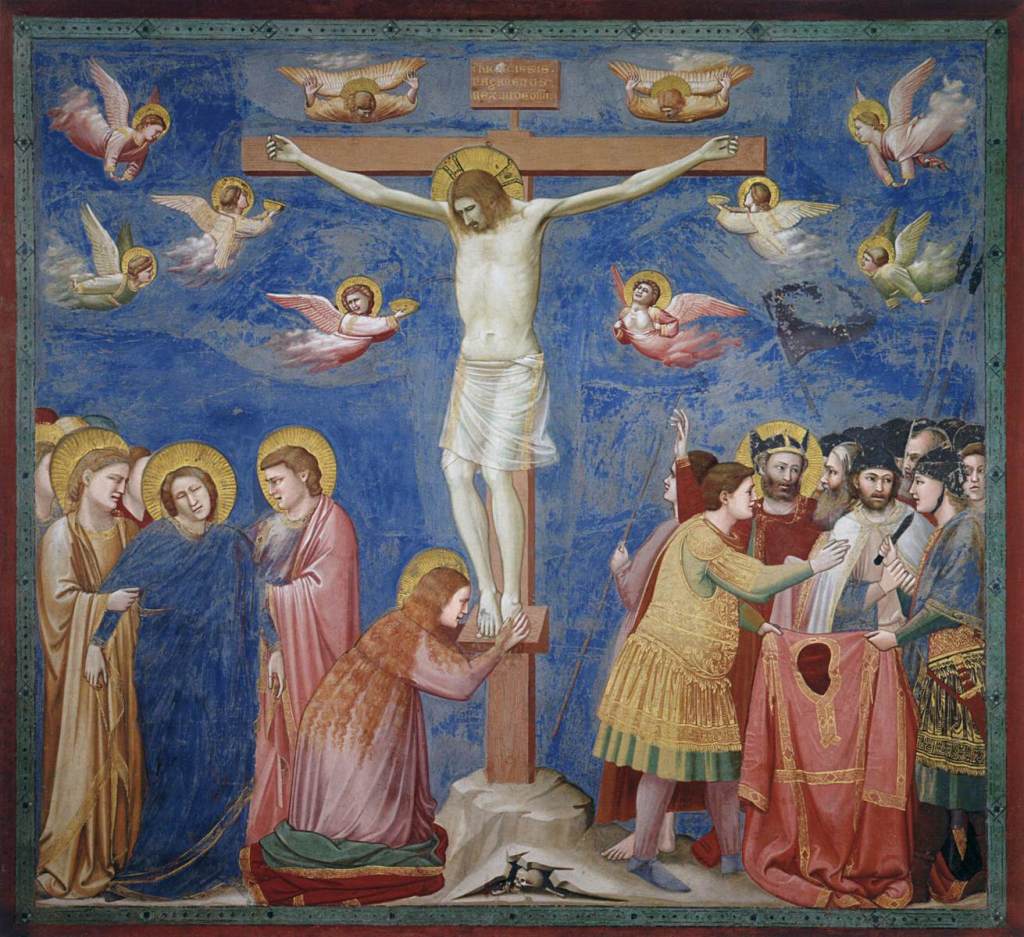

One last image for Scrovegni Saturday before a final summing up next week: Pentecost, in which God hands over responsibility to man, and Giotto remains entirely human, and entirely poetic. I have covered the story before – twice, in fact: on the day itself, with Plautilla Nelli’s little known version in Perugia (Picture of the Day 74), and the following day, with El Greco’s visionary telling of the story now in the Prado (POTD 75) – so do re-read them if you want more background to the story itself.

Giotto gives us a calm and straightforward rendition which, unlike either of the paintings we have seen before, does not appear to be a drama performed for our eyes. On the contrary, there is evidence that we are entirely incidental. But before we look at the painting, let me remind you what the bible says on the subject, in Acts 2:1-4:

And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. 2 And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. 3 And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. 4 And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.

The text doesn’t say how many of them ‘they’ were, but Giotto simplifies to twelve. The apostles sit in an enclosed room, one of the very few identifiably ‘gothic’ buildings that Giotto depicts in the Scrovegni Chapel. It is at a slight angle, and oddly, has no visible door. It’s not at all clear how they managed to get in there, short of clambering through the arcade and over the benches, on which they now sit. Their bottoms spread across the hard wood as they do in the Last Supper, and their feet are visible in the shadows under the seat. In another echo of the Last Supper, those with their backs to us appear to sit with their halos in front of their faces. We don’t actually see the Holy Spirit, but the tongues of fire which reach towards the apostles suggest that the dove must be hovering some way above the roof. This is the point in the biblical narrative when the people gathered outside the room could understand the apostles as if they were speaking in their own language, although Giotto does not include any of these witnesses – but then neither did Nelli or El Greco. However, he doesn’t include Mary either – unlike most other depictions of the story. More on that below.

Matthias was appointed to replace Judas at the very end of Chapter 1 of the Acts of the Apostles, so he should be present here. If we compare this image to others in the cycle, the only ‘type’ who hasn’t been seen before is the person on the far right, a young man with a short – or at least thin – dark beard. This must be Matthias, at the far end of the table from Peter. He is wearing yellow, as Judas used to, almost as if he has taken over the same position on the ‘team’. Six apostles sit along the back of the room, and four along the front. John the Evangelist sits next to Peter, a little further back, and one of the columns of the arcade cuts across his face. This is the evidence I mentioned that suggests that we are incidental – Giotto is not pretending that the apostles have arranged themselves so that we can see them clearly. Despite the column, though, we can still identify him: young, beardless, and wearing the same blue and pink he has elsewhere. Further along, though, another of the apostles is completely hidden by the architecture, a nod to naturalism which we would see as almost photographic. Perhaps it is even a tacit acknowledgement by Giotto that we would probably not be able to work out who this was anyway. The others are equally difficult to identify, as far as I am concerned, with the exception of St Andrew, just to the right of centre with his back to us, sporting the long, curly grey hair, and green toga over a red robe that we have seen before (e.g. 105). Next to St Andrew, chatting away to the newcomer Matthias, is St Bartholomew in his flashy patterned fabric.

I said above that this image is poetic, and yet initially it might seem rather mundane: there is apparently nothing remarkable about it. The first thing to suggest otherwise is the overtly Gothic architecture. Despite their ‘Roman’ clothing, the apostles are seated in what was for Giotto a contemporary building – and this is entirely apt. This is the point in the biblical narrative at which the apostles can be understood by all the nations of the world, thus enabling them to head out and evangelise. In other words, this is the point at which they take over from Jesus, and become his vicars – his representatives on earth: the priesthood is born. There are no women present – Mary would have been out of place in this particular version – and the reason why becomes clearer if we remind ourselves where we are in the chapel.

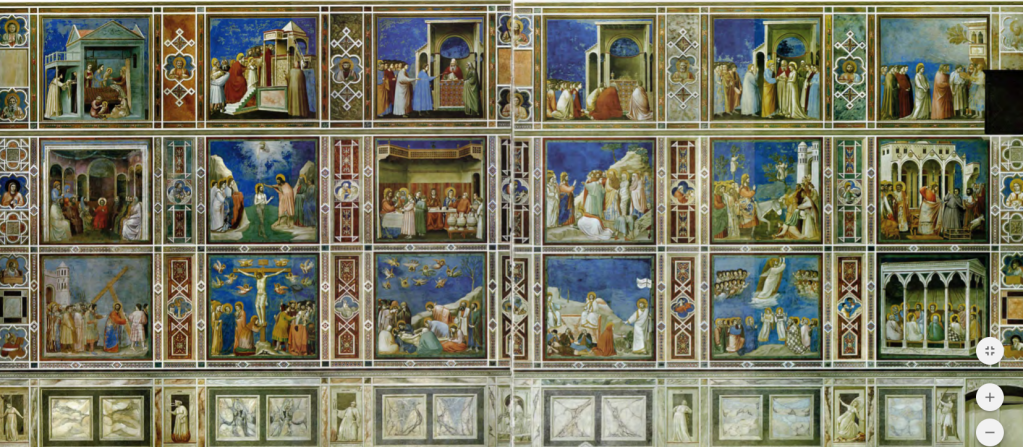

We are at the bottom right of this image, at the end of the story, and close to the high altar. From here, you can almost imagine the apostles stepping out of the fresco to officiate over the mass. Their role, Giotto says, is the same as that of the contemporary priest, who is effectively their successor, and of course, when this was painted, the idea of a female priest was unthinkable (as for some it still is today) – hence Mary’s absence. And, if they are like the contemporary priest, it makes sense that they would be in a gothic building.

It is not irrelevant that the scene directly above Pentecost is The Expulsion of the Money-changers from the Temple (see 102), in which Jesus effectively cleanses his Father’s house. The temple itself is depicted with round-topped arches. This comparison of architectural styles is quite common in Northern European paintings of the Nativity, and represents an idea of progress. The round arches, like those used in classical Roman and subsequent Romanesque architecture, represent the old order – as embodied here by Solomon’s temple. On the other hand, pointed Gothic arches were seen as ‘modern’, and so stand for the new order – the Church. Above these two paintings, Mary processes towards her parents’ house, and, in terms of the Scrovegni Chapel, towards the Annunciation, effectively a mystical marriage between herself and God. When she becomes pregnant, she is effectively, like Temple and Church, the house of God. In much medieval theology there was a direct equivalence between Mary and Ecclesia, the personification of the Church. Thus in the column of three images close to the altar we have different representations of the church, the temple and the church again, one on top of another.

In this view of the chancel arch Pentecost can be seen, at an angle, at the far end of the wall on the left: its proximity to the High Altar is, I hope, clear. Almost directly opposite, just this side of the window at the far end of the wall on the right, is The Last Supper, the painting to which it is most obviously related in terms of composition and setting. We have come full circle. On the right Jesus presides over the Last Supper, as he institutes the Eucharist. His passion, death and resurrection lead us away from the altar and back again, until with Pentecost the apostles are once more next to the altar, and are ready to continue Christ’s mission on earth.

So much is similar between these two images. Peter and John still occupy places at the ‘head’ of the table – although in the Pentecost they are facing towards the high altar in the chapel. Indeed, Peter is either looking at us, or at the altar itself, which lies on the diagonal in which he is looking. Andrew and Bartholomew are sitting next to each other again, although, without Jesus, the latter has turned to talk to Matthias. The gothic arcade creates more of an enclosed space, perhaps, but we still have access to the scene, in the same way that we would if looking through the rood screen in an Anglican church (although I’m afraid this is not entirely relevant to Giotto’s Italian experience). As previously mentioned, the apostles have the same weight in both, with their bodies pressing down on the bench and their shadowy legs visible below. And while those with their backs to us still have halos apparently in their faces, those halos are notable different. In The Last Supper they were silver, although this has tarnished to black. By the time we get to Pentecost they have been ‘promoted’, and all rejoice in the same gold halos previously only given to Jesus. They are now his representatives on earth, and should be seen as such. It is a minor difference, perhaps, but poetic genius nonetheless.